While I was doing research on Psygnosis it quickly became apparent that the story leading up to Psygnosis was much more interesting than the story of the company itself.

Hence this article is a bit atypical, and will pretty much only focus on the time leading up to Psygnosis being founded.

Psygnosis would rise to 16-bit fame in the mid-’80s and early ’90s and in the process become one of the most prominent software houses in UK history. Its story and origin should be found years earlier, in the blue-collar city of Liverpool, when the very birth of the UK computer and software industry came about. It’s a story of early computer programmers, promises, fast cars, young millionaires, and dubious business ethics.

Before the 1960s, the port city of Liverpool, in North West England was probably most known as the port of registry for the ill-fated ocean liner RMS Titanic… and for being just another working-class city.

This perception would all change when manager Brian Epstein and producer George Martin, assisted the small Liverpool act The Beatles to become the most influential band of all time.

By the late ’70s, Liverpool’s industry was in a hard decline and the city had some of the highest unemployment rates anywhere in the UK. The city needed a new injection of entrepreneurship that once again would speak to the young and restless, giving them hope of a brighter future.

Like with the pop counter culture wave of the ’60s, entertainment was yet again becoming a significant driving force. Aspiring teenagers, self-taught and self-motivated, just like the generation before, would find their ways but this time in computers and software.

Bug-Byte

In 1980 two young Oxford graduates, Tony Baden and Tony Milner established Bug-Byte in Liverpool as one of the very first professional computer game companies in the UK.

Baden had the same year, while he was still attending Oxford, bought the newly released Sinclair ZX80. A domestic produced microcomputer by Sinclair Computers. Before he left university he already mastered the machine and had written his first programs.

Bug-Byte essentially would change the game development business from what at the time typical was a bedroom operation and move it into a full-fledged professional industry, where office space and proper marketing budgets were just as an essential part of it as the game development itself.

Bug-Byte grew quickly and had within the first year a dozen employees. Three of those, Mark Butler, David Lawson, and Eugene Evans went on to found Imagine Software in 1982 to publish Lawson’s newest game Arcadia, a title that ended up being hugely successful. All three had known each other from the time before Bug-Byte, where Butler and Evans had worked together at Microdigital, one of the very first computer stores in the UK. Here Lawson, who was a frequent visitor, had bought his first computer and had swiftly ventured out programming games in Machine Language.

Imagine Software

Imagine Software quickly rose to success and recognition and was noted for its polished, high-budget approach to packaging and advertising.

1983 went on to be a great year for the company with many critically acclaimed titles and even a “Best Game of the Year” award.

With the enthusiasm surrounding the new generations of computer games and with the emerging software houses pioneering the new market, BBC, in late 1983, sent a documentary crew to interview the young team. While everything on the outside looked fabulous just like Butler’s paycheck and lifestyle, they ultimately found a company in deep crisis, with serious financial issues and mountains of debts. Imagine was not only a victim of financial negligence and dubious business deals but also of its own ambitions, and it was all being documented by the film crew.

You can find the documentary, Commercial Breaks: The Battle for Santa’s Software by BBC here. An absolute must-see.

Imagine Software was at the time working on two out of six planned big concepts and high profile so-called Mega-Games. These games were designed to push the boundaries of the fairly limited 8-bit hardware of the time, even to an extent that they were meant to be released with hardware add-ons that would attach to the ZX Spectrum and increase the machine’s memory significantly.

The Mega-Games along with the extra hardware was rumored to retail around £40-£60, up to ten times more than the average Spectrum game. Not only extremely ambitious but also very naive in a time when a £10 game was considered too expensive.

The utopian bet on the Mega-Games and the company’s rapid expansion with fancy offices, state of the art computer hardware, a hundred payrolls to fill, and Butler’s racing team to finance it was becoming obvious (well not really since Imagine didn’t have a real accountant to keep track of the finances) that the company was about to implode on itself.

For the 1983 Christmas, Imagine went full-blown frontal, producing hundreds of thousands of copies of their games, but sales were already on the decline. Imagine had yet again invested heaps of money without any real chance of getting any return, The only thing they ended up with was a warehouse full of unsellable games and a long line of creditors.

Cavendish, an investor who had invested 11 million pounds in the Mega-Games project wasn’t impressed with Imagine, the progress, and wanted the invested money back.

Lawson, Butler, and former Chief Financial Officer Ian Hetherington, who was brought in to clean up the financial mess, went on to secretly co-found another company, Finchspeed, with the intent of transferring over Imagine’s assets but without the debt. Lawson and Hetherington, who initially were the “masterminds” behind the Finchspeed scheme, believed they could acquire parts of the sinking company’s assets together with some loyal staff members, with the goal to continue to work on Bandersnatch, one of the heavily advertised and hyped Mega-Games.

So all while Imagine was going down in flames, Lawson, Butler, and Hetherington’s allowed for themselves to use Imagine’s offices cost-free, for however long Imagine still existed. In return, Finchspeed would pay Imagine £40,000 for use of its equipment to continue to develop Bandersnatch. 50% of any net profits and up to £625,000, from any sales, would also go to Imagine. Butler, Lawson, and Hetherington knew that the likelihood of Imagine still being around when the game eventually was completed was highly unlikely, and they, therefore, could carry on care and cost-free. This was not only being a really dodgy move, not only towards the rest of Imagine’s employees but also it’s creditors. This was of course all highly illegal. Imagine Software already had a winding-up petition, from the spring of 1984, filed against it in which case British law has measures to prevent dubious and creative business ethics like this.

All Imagine’s assets would be liquidated in compliance with British law and to what would benefit its creditors the most.

Finchspeed

Finchspeed ended up with a business arrangement with Sinclair Computers. Sinclair had released its new and powerful 16-bit Sinclair QL computer earlier in 1984 and was now on the lookout for funding new software to better the computer’s chance of survival in the market. Bandersnatch seemed the perfect match for the QL and Finchspeed bought the rights to the Mega-Games at the Imagine liquidation auction for £700 with the condition that Imagine’s creditors would be paid a portion of any income the Mega-Games might eventually generate.

Ocean Software went ahead and acquired the rest of the company and would end up using the Imagine label up until 1990.

While progress was being made on Bandersnatch, the sooted Finchpeed name needed to go, along with Butler, a fresh start was needed.

Lawson and Hetherington founded Fireiron the same day that Sinclair Research signed the contract with the duo, paying them to port and finish the Mega-Games to the QL computer.

Unfortunately, like with Imagine, Fireiron was over-ambitious and over-promising and was spending way too much of Sinclair’s money without any real results. Bandersnatch was promised to be released in the first part of 1985 but with QL sales plummeting and financial trouble at Sinclair, the company eventually pulled out of the deal. Production of the QL was suspended at the beginning of 1985.

While Sinclair Research still had the copyright to the Mega-Games and the Bandersnatch name, Fireiron hatch a plan to continue the development of the game. With Sinclair busy selling off its computer business to Amstrad no one noticed that Fireiron became Psygnosis and Bandersnatch became Brattaccas – not even Imagine’s creditors who still were supposed to receive parts in the revenue the Mega-Games would eventually make.

I guess persistence pays off, at least for Lawson and Hetherington, for everybody else involved not so much.

Built upon the much-hyped Mega-Game Bandersnatch, the game was finally completed and released as Brataccas in early 1986, as Psygnosis first title. In North America, it was published by Mindscape the same year.

Psygnosis

Lawson and Hetherington founded Psygnosis, with Jonathan Ellis who was put in charge of the business side of things by new investor Robert Smith. Psygnosis would become known for its over the top graphics, hard pumping audiotracks, and for its awesome and coherent packaging designs.

Full-time artists maintained an extremely high standard and a very much cohesive visual design across the board. The extreme focus on the audio-visual left, for the most part, things to be desired gameplay-wise.

Many of the employees and the tools used at Psygnosis ended becoming a big part of the upcoming demo-scene.

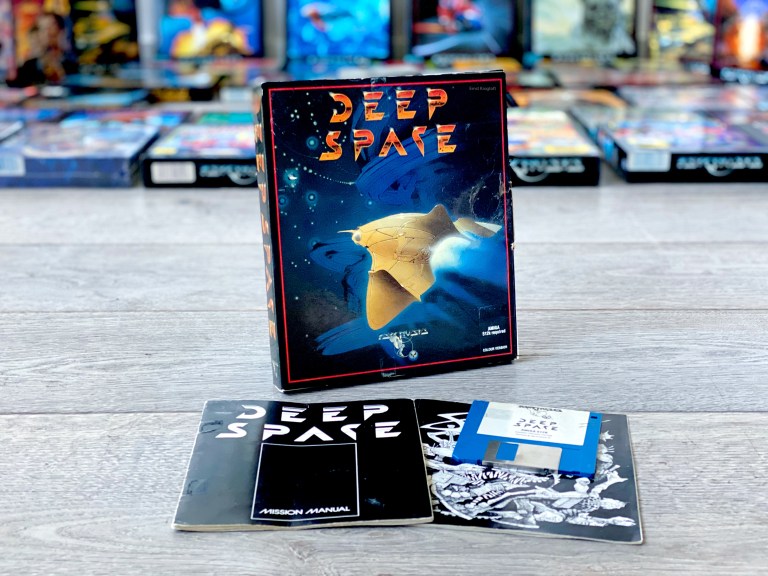

Deep Space, one of only a few titles produced by Psygnosis in 1986. A complex space exploration game. The box artwork was very distinctive with a black background and fantasy artwork bordered in red. This style was maintained for the better part of 10 years

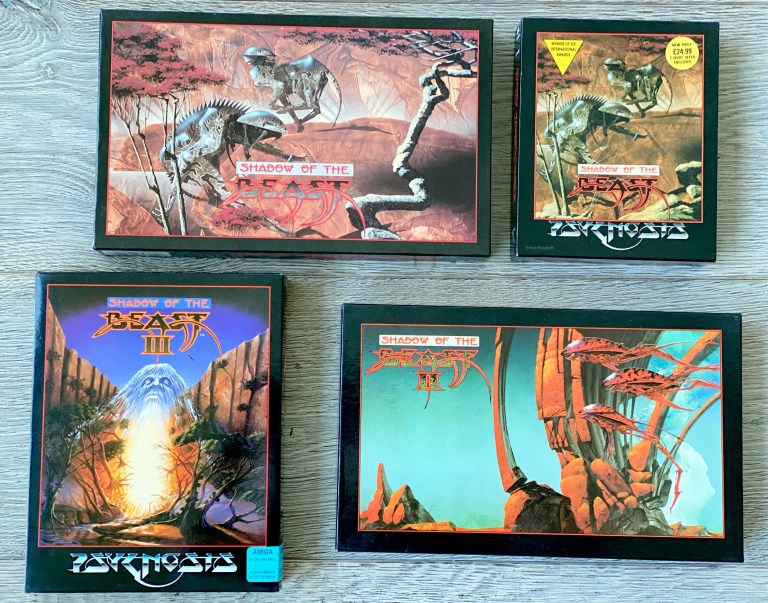

The landmark title Shadow of the Beast was released in 1989, it became Psygnosis’ biggest success until Lemmings were released years later. Two titles followed in the coming years but none of them became as popular or successful as the original. I’ve earlier written a small article on the series here

Psygnosis used the Psyclapse label for a few of its titles. The Psyclapse name was taken from another Mega-Game title that never materialized

Psygnosis would use different box-formats, all would feature the same design with a black border and a beautiful atmospheric fantasy cover image with a red pinstripe

The success of the British computer business should not only be found in entrepreneurs like Clive Sinclair and companies like Imagine and Psygnosis but also in the British government, which in the late ’70s and early ’80s saw the computer industry as a crucial and important aspect of the country’s future economical and industrial performance. Margaret Thatcher’s government ended up being extremely supportive of the country’s computer industry and her government would supply more computers to schools than any other country in the western hemisphere at the time.

The impact companies like Sinclair Computers had on British society was undeniable. There was a saying in the ’80s when new challenges arose “think of Mr. Sinclair and his microcomputers”.

With the government supporting and supplying computers, innovated and built in the UK, to the British people and institutions the majority of software needed wasn’t coming from the other side of the pond or even from Japan, it was developed in Britain.

2 thoughts on “Psygnosis, the long and winding road to becoming a 16-bit UK powerhouse”