Welcome, dear reader. After more than a decade of writing this blog, it struck me that I’ve never stopped to tell a bit about myself. What follows is, in many ways, a tribute, not just to the games and computers I’ve spent a lifetime exploring, but to my parents, whose own journeys through technology shaped mine. They’re no longer here, but their stories remain at the heart of everything I do, and without them, Retro365 would not exist.

I was born in the spring of 1979, at a moment when personal computers were beginning to slip into offices, schools, and living rooms, reshaping the world in ways few could yet imagine. For me, though, computers weren’t some distant revolution, they were part of the air I breathed. Both my mom and dad worked in technology, and computers were as ordinary to me as toys or storybooks. To explain why this blog exists, and why these old games matter so deeply to me, I have to tell the story of my mom and dad, whose paths in life got me heavily invested in not only computers and games but everything that came to define them.

My dad’s story traces the arc of 20th-century technology itself. He was born in rural Denmark in 1930, into a world still bound by tradition and local rhythms. When the German occupation arrived in 1940, his family relocated to the capital city of Copenhagen, a city soon marked by ration lines, curfews, and German soldiers pressing in on everyday life. Out of the turbulence came a lifelong love affair with technology, starting with cameras and photography.

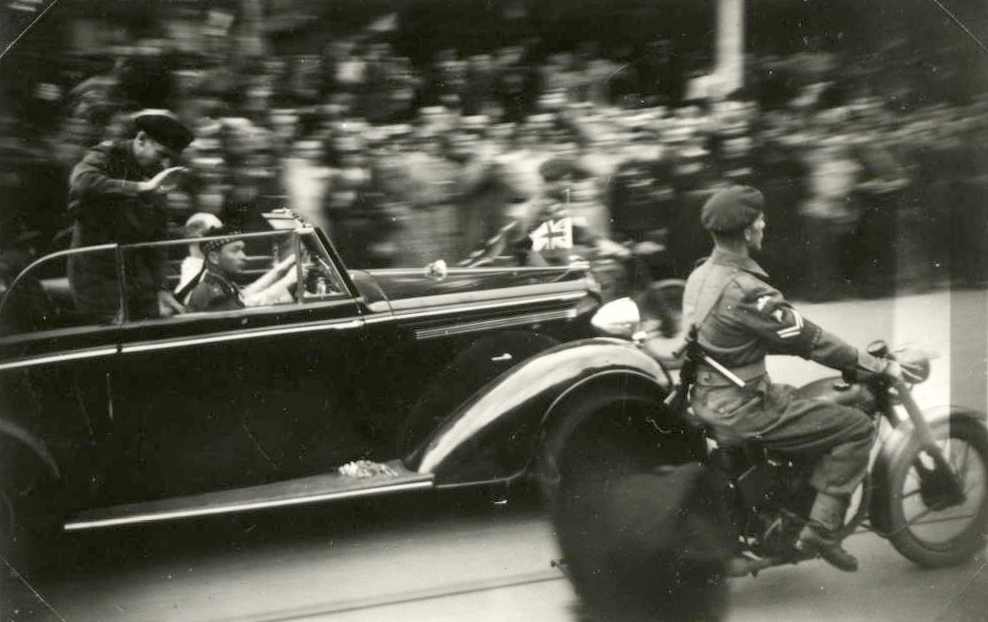

British Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery is saluted by the Danish people as he is driven through the streets of Copenhagen a week after his troops had liberated Denmark from German occupation in May 1945.

Photo by my dad, for which cameras and photography became his first love affair with technology.

After the war, he entered the Polytechnical University, where he earned a degree in electrical engineering before serving in the Danish military as both an engineer and a telegraph operator. For most people of his generation, the world remained a small place, bounded by family and one’s local area. But my dad carried a restless curiosity, an avid hunger for the wider world. He went to sea, taking work as a radio and telegraph operator on commercial ships sailing east. Journeys that carried him into ports and cities that most people of the time knew only from books or grainy newsreels. The far east wasn’t just a place on a map, it profoundly shaped his imagination, his worldview, and ultimately the way he approached technology, with an open and curious mind.

While the Second World War was over, war was now raging on the Korean Peninsula, a reminder that peace was not a matter of course. My dad returned to Denmark, where he worked a few different jobs before getting involved in the rollout and establishment of the Danish national television broadcast infrastructure. And as the new medium connected households across the country, another revolution was stirring in the background.

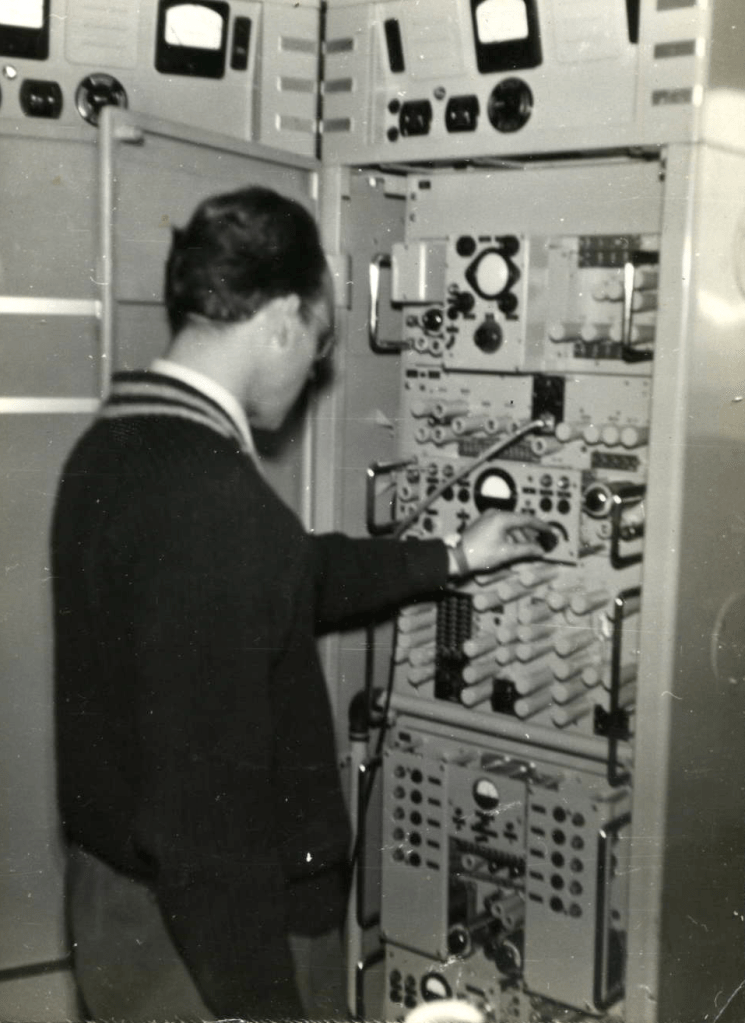

My dad was at the forefront of technology his whole life. Here, working on the early national TV broadcast rollout in 1955.

Across the ocean, in America, mainframe computers were beginning to appear in universities, research centers, and large companies. These machines were enormous, temperamental, and demanding, nothing like the devices we now slip into our pockets. To operate them required a team of engineers, people who understood the delicate interplay of punch cards and circuitry. For my father, with his background in electrical engineering, the transition felt natural. In the 1960s, he joined IBM, the company then synonymous with computing’s future.

At IBM, he became a software engineer, working on projects that helped knit together the modern world. One of the most ambitious was SASCO I, Europe’s very first computerized flight-booking system, which ran on the IBM 1410. Only America’s Sabre system had come before it. To be part of something so new, so foundational, was the kind of challenge my dad loved. He was helping build systems that allowed people to see the world, just as he once had, years earlier, from the deck of a ship.

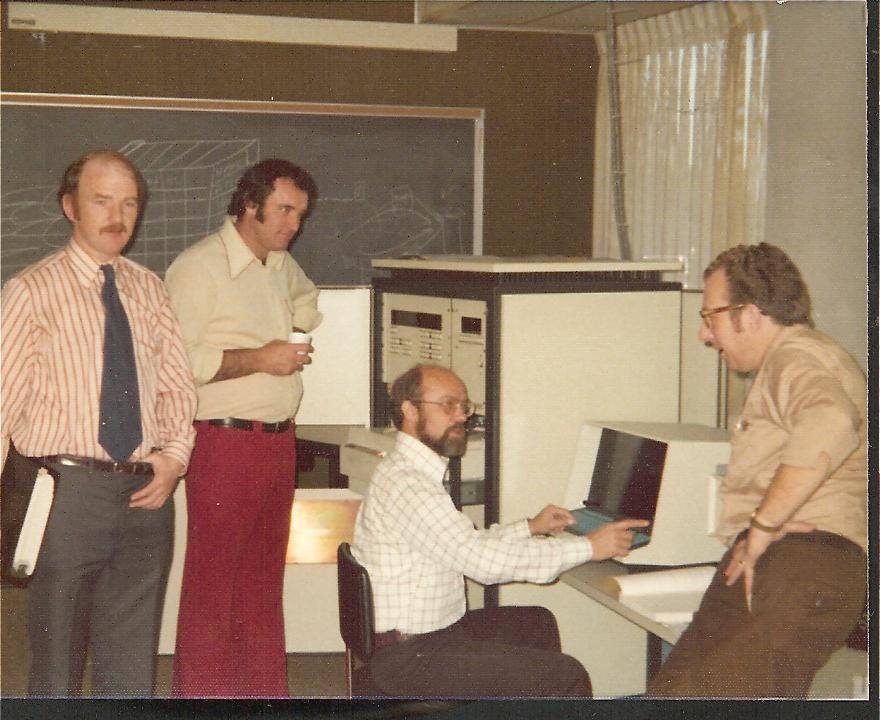

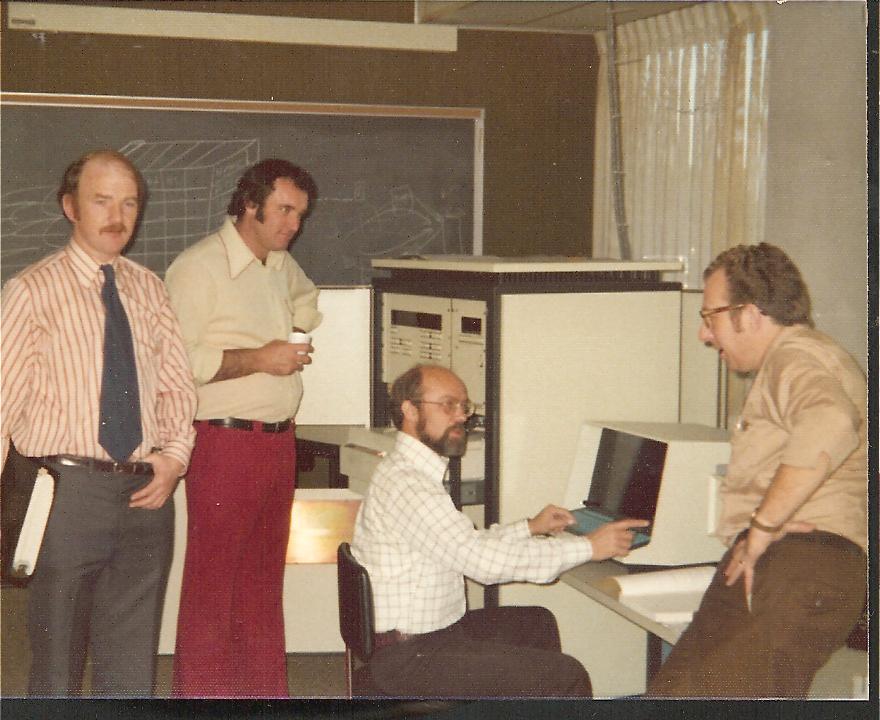

One of my dad’s numerous work-related visits to the United States in the 1970s.

Here, sitting in front of a 1970s-era terminal connected to the adjacent minicomputer.

Photo from 1974.

By the early 1970s, my dad’s path carried him into a company that would become an essential part of my family’s story. He joined Max Bodenhoff A/S (A/S meaning publicly traded company), a name that had stood in Danish business circles for 60 years. The company had been founded at the dawn of the century by Max Bodenhoff, my grandfather’s uncle on my mother’s side.

In its early years, the company would lease out and service typewriters for businesses across the country. Max would, in his truck painted with bold advertisements and typewriters loaded up in the back, travel near and far, urging people to see what was coming. To him, typewriters weren’t just mechanical curiosities, they were the future of office work. He was right. Demand grew quickly, and so did the company.

When the roaring 1920s arrived, Bodenhoff began investing in Hollerith punch-card technology, the precursor to modern computing. From 1920 until 1949, the company handled all of IBM’s business in Denmark, covering both typewriters and punch-card systems.

The IBM partnership was sealed in no small part by Max himself. In 1935, he traveled aboard the SS Washington, a luxury liner bound for New York. Like so many who passed through Ellis Island, he arrived to have his papers inspected, though unlike most, his destination was IBM’s headquarters in upstate New York. There, he forged a personal and professional bond with IBM’s legendary CEO, Thomas J. Watson. The result was decades of cooperation with Bodenhoff leasing, selling, and servicing IBM products across Denmark.

When IBM decided, a few years after the war, to establish its own formal presence in the Nordic countries, it invited Bodenhoff to fold its operations under the IBM name, but Max wanted the company to remain independent. On January 1, 1950, the entire punch-card staff moved over to the newly established IBM A/S, while Max himself received a generous pension from Watson, “more impressive than any Department Manager of the Danish Ministry,” as it was later described. The two men remained close friends until the end.

It was into this legacy that my dad stepped during the mid-1970s. At Bodenhoff’s headquarters in central Copenhagen, he worked on designing and tailoring complete computer systems, hardware, and the custom software that brought them to life. It was an age when offices were beginning to feel the full weight of digitization, and Bodenhoff was at the forefront.

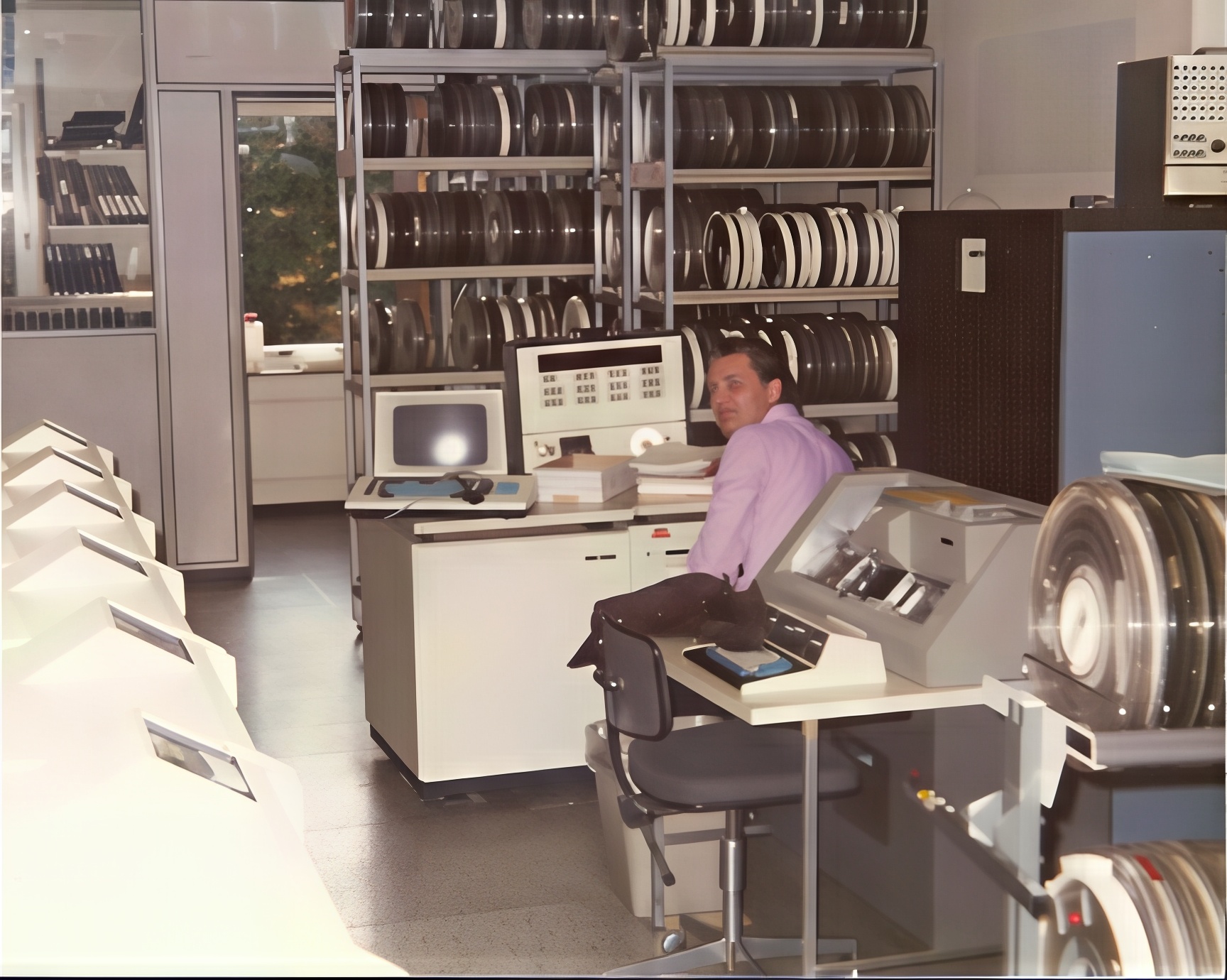

The computer department with miles of magnetic tape storage.

Photo from 1974.

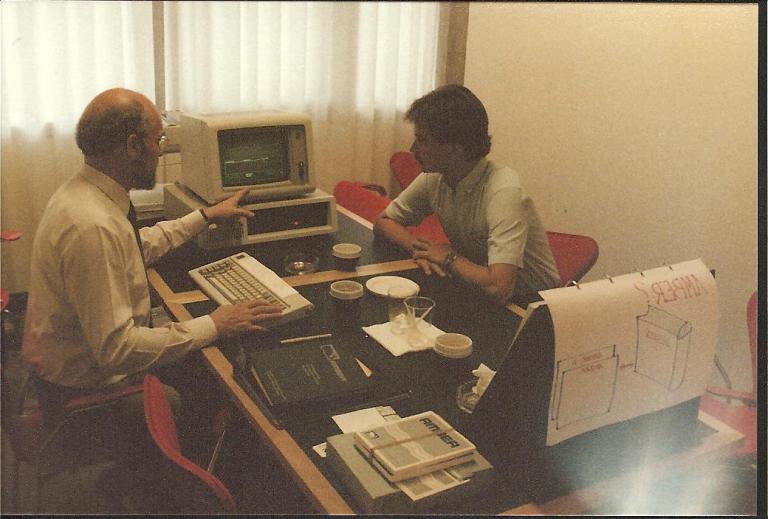

Signs for a tradeshow are being prepared. The Bodenhoff System 3, a complete custom-tailored computer system, would set you back $60.000 in today’s money.

Photo from 1981.

Inside the company walls, life wasn’t only about business. My dad’s personal story took a dramatic turn in those years. His first wife, terminally ill, passed away far too soon. Out of that loss, something unexpected took root, a new love, this time with a woman who would change everything: my mom. She was working at the company alongside her father, Ib Bodenhoff, who had joined the ranks from early on and now served as CEO. As the company grew into a leader in digital office solutions, my parents’ relationship deepened into marriage. Before long, the promise of new life arrived. In 1979, my brother and I were born, twins entering a world already bound up with technology, history, and the machines that were beginning to define a new era.

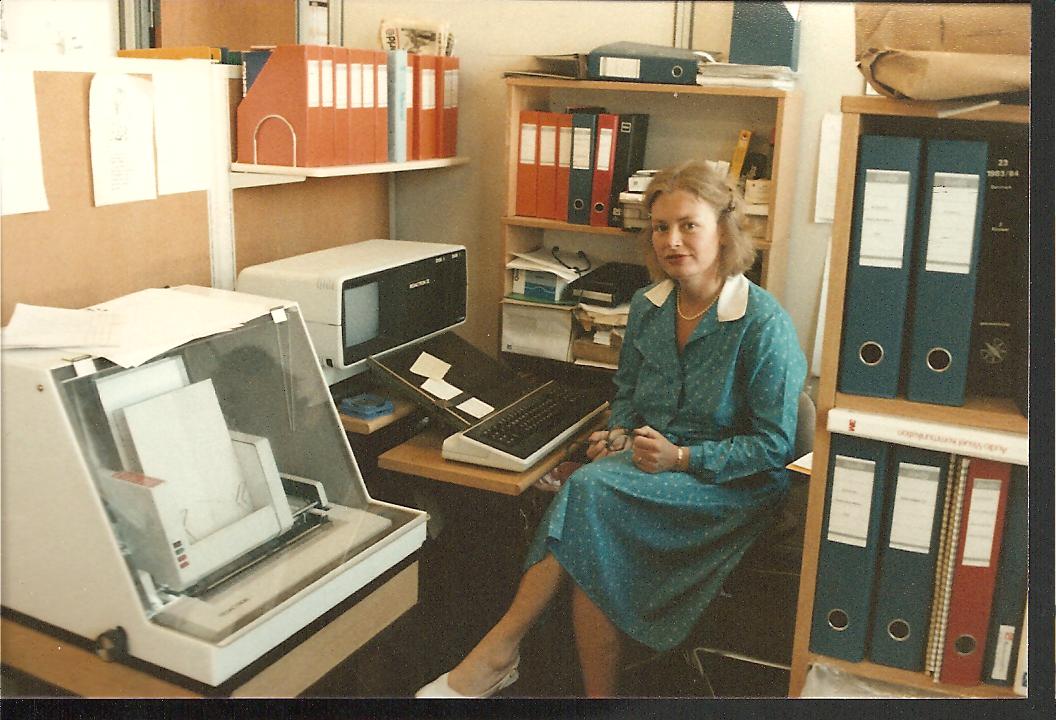

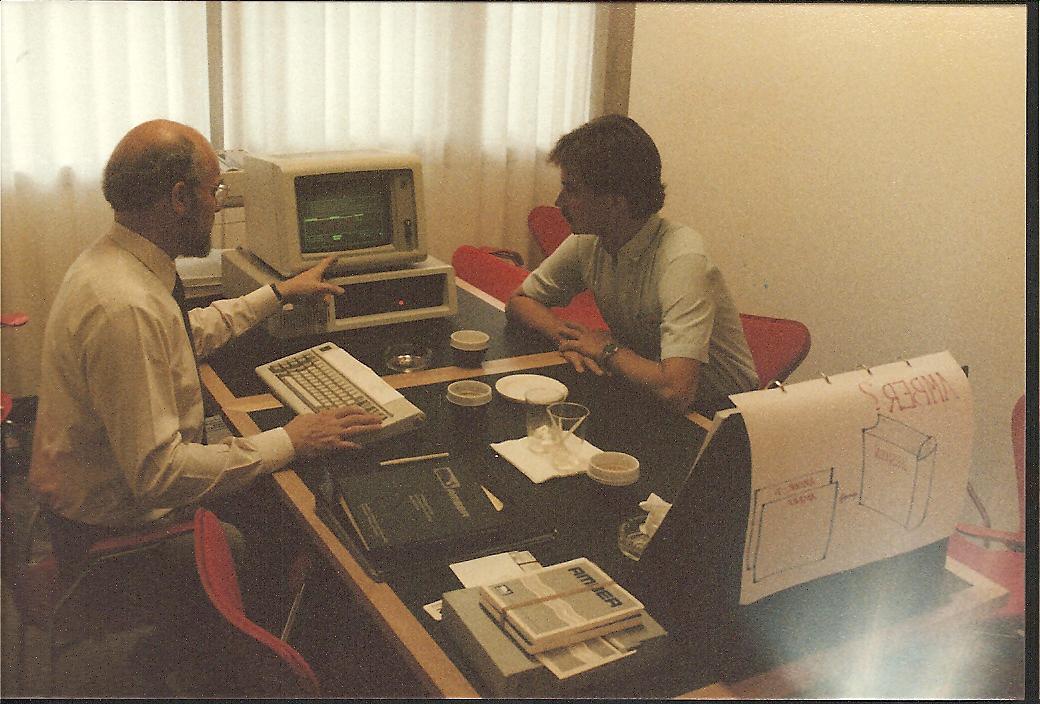

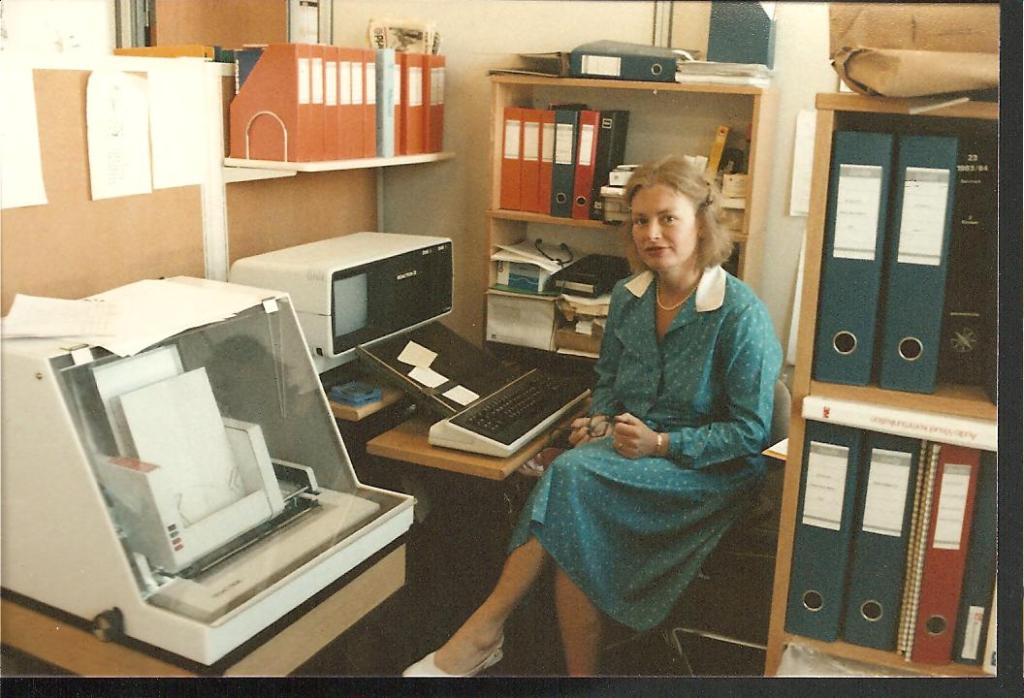

Pictures of my mom while working at the Bodenhoff office in central Copenhagen.

Photos from 1981 and 1983.

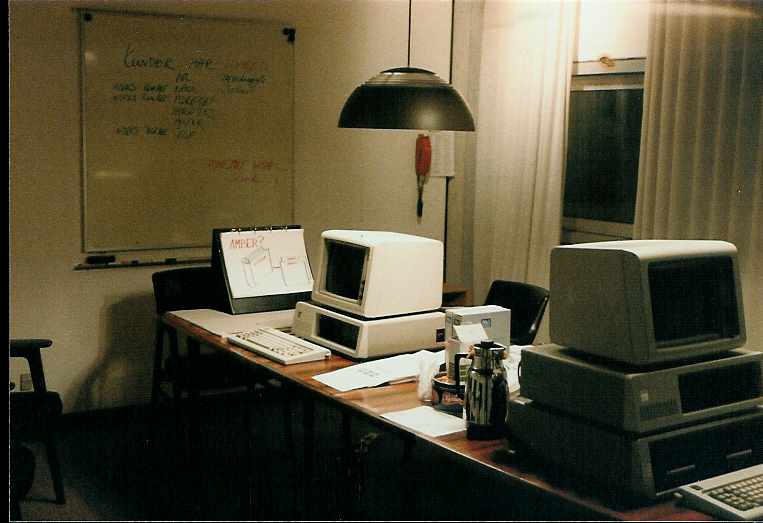

By the early 1980s, my dad’s restless energy pushed him forward once more. He left Bodenhoff to establish his own company, Amber Scandinavia, an independent branch of Dutch-owned Amber International. Here, he threw himself into software programming and system application implementation.

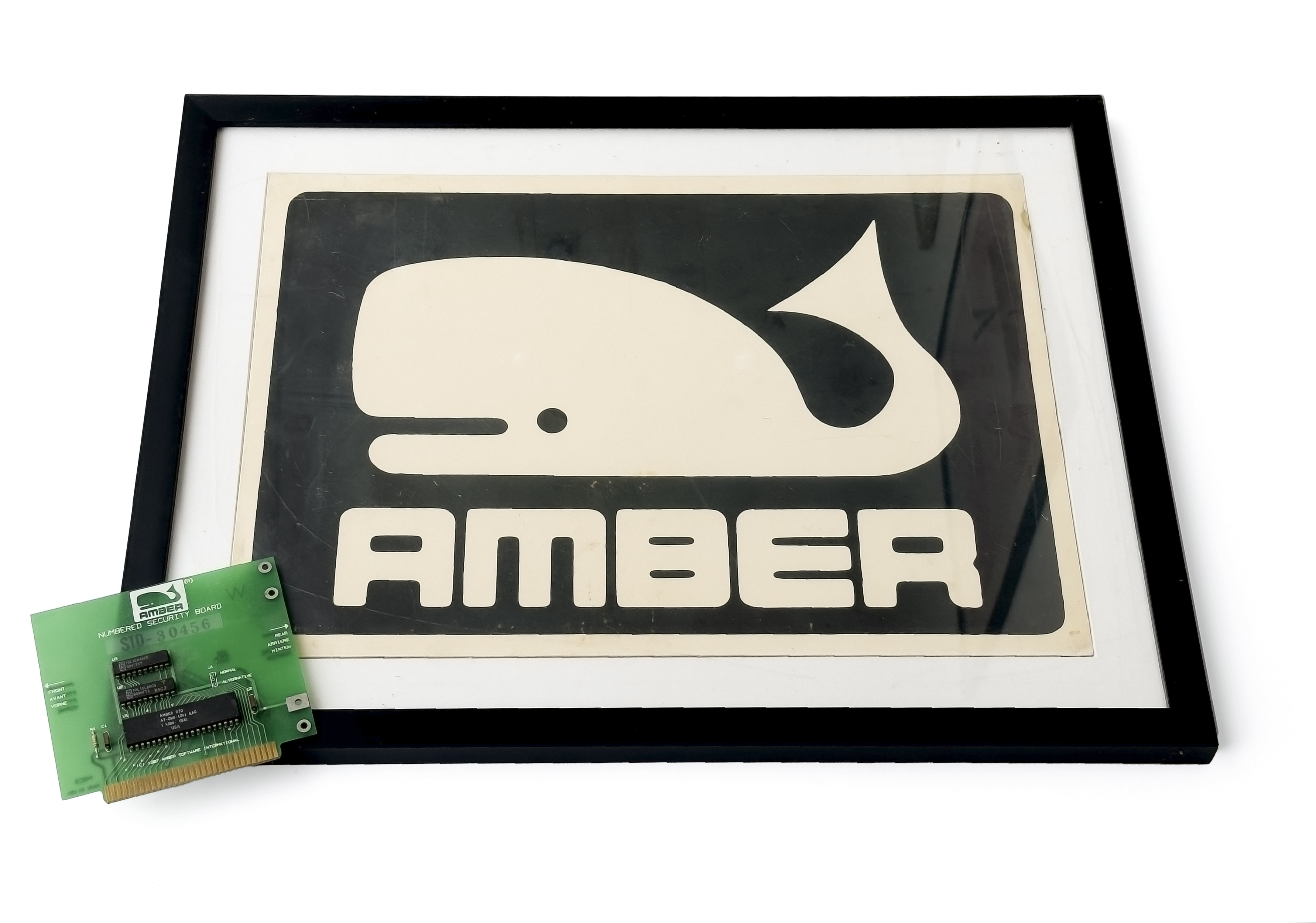

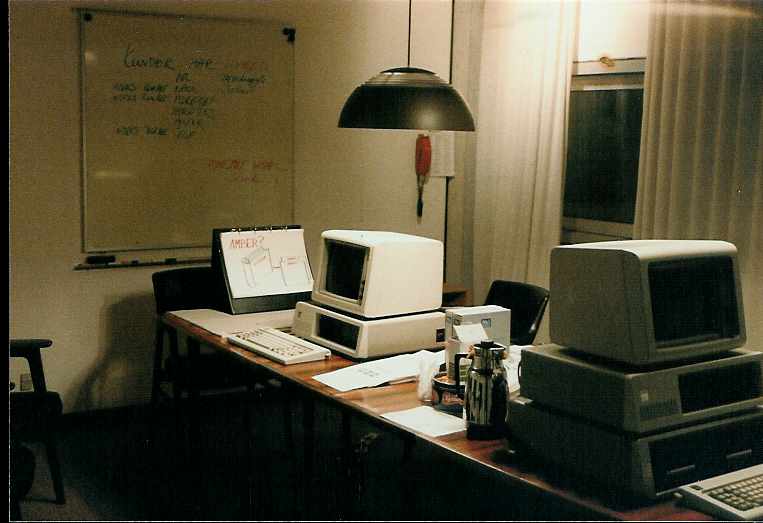

Amber Scandinavia, the system application software company my dad operated from the early 1980s up into the early 2000s.

In the left-hand corner, a 1980s 8-bit ISA security card, required for the software to run.

Choosing to work from home, all while having an office and meeting space strategically placed in Copenhagen, my dad’s home office would become a magical place where shelves gave way to the sheer weight of books, covering nearly all programming languages. Scattered around were early microchips and printed circuit boards. At the heart of all was the mighty and expensive IBM PC, a device IBM had put together from off-the-shelf parts in less than a year. No one, not even IBM, could have guessed that the machine would become one of the single most important computers of all time. For me, it was far more personal. It was the computer that shaped my life.

My dad was an IBM man at heart, through and through, and when the IBM PC had been introduced in 1981, it quickly found its way into our family. The computer was foremost a business machine, and that was what my dad used it for, but his fascination with the machine rubbed off on us kids, who soon enough were writing out commands in the DOS prompt, poking around in the Autoexec.bat and Config.sys files, trying to understand why a program would, or wouldn’t, run. Nothing was off limits, and we became best friends with the machine and whatever software was available on it. It didn’t matter if it was text editors, utilities, or, of course, games. Every floppy disk that landed on our doorstep became an invitation to explore.

My dad (and my older brother, from his first marriage) with his IBM Model 5150, the original IBM PC.

The computer has outlived my dad and is today fully functional, carefully restored, and curated by my twin brother.

Photo from the early 1980s.

The IBM PC became an integral part of our household. Notice the Bernoulli box underneath the machine on the right-hand side. This was a dual-cartridge disk system for 5 MB disks, by Iomega, designed to match the IBM PC case.

Photo from 1984.

Through my dad’s computer groups, a steady trickle of disks arrived. Many carried games, simple at first, text characters clambering across the screen or graphics limited to the awkward but somehow beautiful 4-color CGA palette. Yet those early titles were magical. Exploration turned into play, learning, and inspiration.

Meanwhile, our family story was still unfolding around us. When my granddad passed away in 1982, my uncle took over Bodenhoff A/S now owned jointly by him, my mom, and the other shareholders. My mom stayed with the company as his secretary, and later she too began working from home. She would return with exciting machines and devices that filled our house.

While we loved the IBM PC and what else was brought into our home, as the decade wore on, we couldn’t ignore the machines we saw at friends’ houses. The Commodore 64, and later the Amiga, dazzled us with their colorful graphics and rich soundtracks. By comparison, our IBM PC looked austere, even clunky. Yet there was something about the PC that gripped us. It was a computer that had to be operated, tinkered with, persuaded to run. For us, that challenge made it irresistible. As the ’80s gave way to the ’90s, the PC emerged as the home computer of choice, eventually eclipsing all rivals, just as our dad foresaw.

Floppies with handwritten labels piled up quickly, passed hand to hand. But my dad, being a developer himself, believed in supporting others who made software. Gradually, original boxes began to line our shelves, birthday presents, Christmas surprises, tokens of a household where curiosity and play went hand in hand.

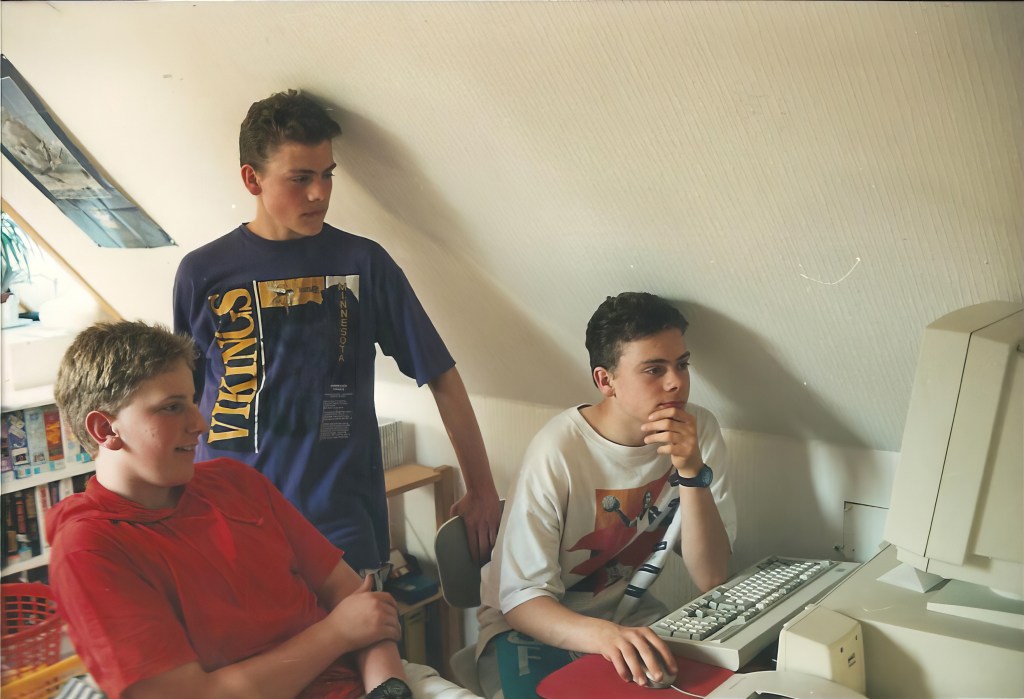

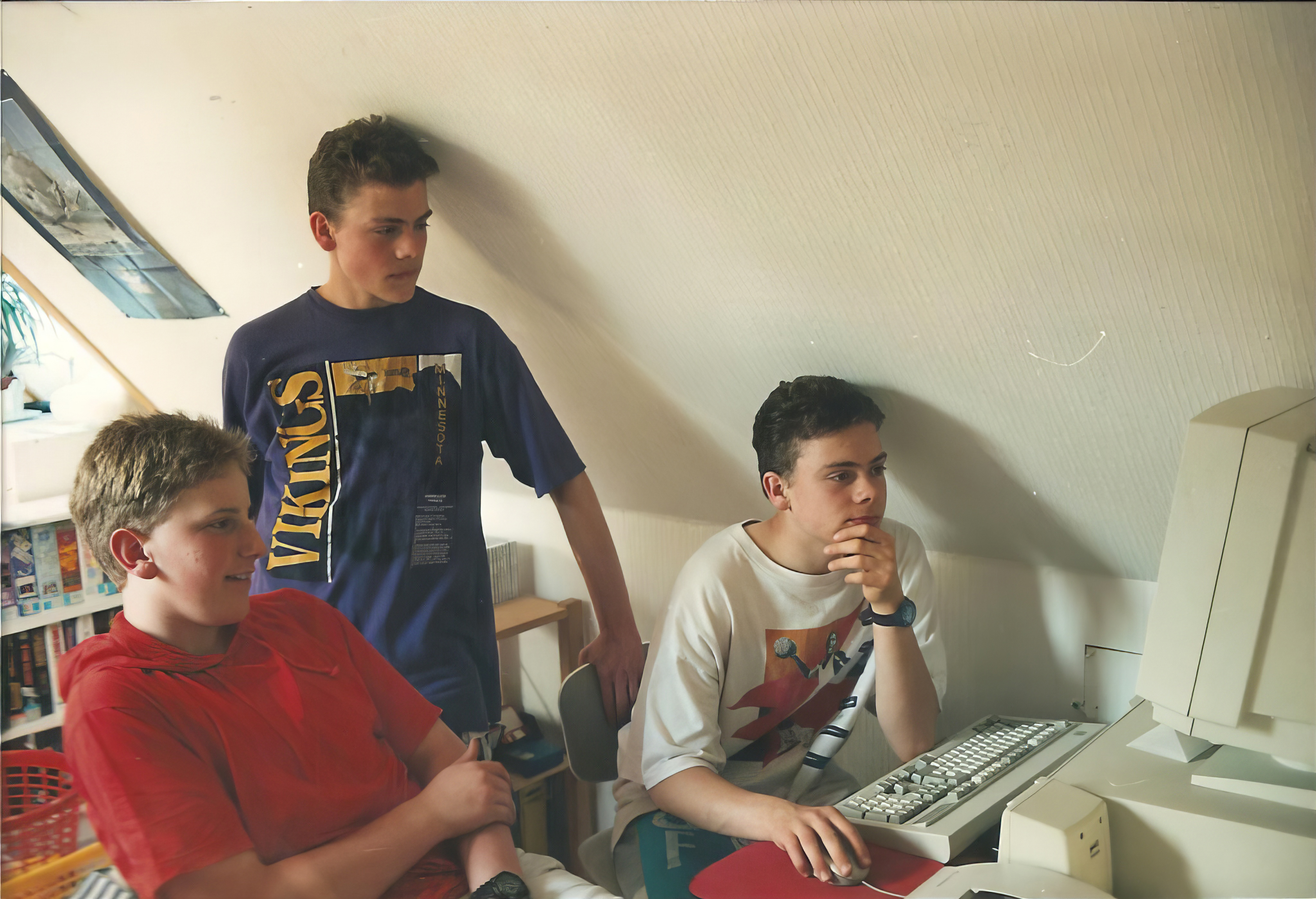

Our room around Christmas 1991—me sitting in front of our Intel 286–based IBM PS/2 Model 50, a machine provided by my mom’s company.

We played hundreds of games, but it was the adventures of Sierra On-Line that captured our imaginations the most. King’s Quest, Space Quest, Police Quest, each one felt like stepping through a doorway into another world. They were challenging too, especially with English as a second language. We didn’t realize it at the time, but every parser command we typed, every copy-protection question we fumbled our way through, doubled as a free English lesson. We absorbed not just vocabulary, but fragments of culture, humor, and politics hidden inside.

My brother, a childhood friend, and I, sitting in front of our IBM PS/ValuePoint 486DX2-66 in 1994. The shelves in the back display some of our beloved Sierra On-Line games: Space Quest V, Police Quest 3, King’s Quest V, Quest for Glory 3, and Leisure Suit Larry 6. On the wall is a poster from Aces of the Pacific.

By the mid-1990s, when I entered high school, my focus began to shift. While living in Michigan in 1995–96, I bought what would be the last games of my childhood. I brought them back home with me, but before long, I had more or less stopped playing. Still, they never truly left me. Their stories, their craftsmanship, and the sense of wonder they sparked lingered, planting the idea that I might one day build worlds of my own. In time, that spark guided me toward a career in 3D, visual effects, and animation—turning the computer into a tool not only for play, but for expression.

In 1999, when my mom and uncle sold Bodenhoff to Japanese Konica Minolta, a long family chapter quietly closed. Around the same time, another began. I found myself drawn back to the games of my childhood, not just to play them, but to preserve them. One by one, I started replacing the old pirated disks with originals, rebuilding a library piece by piece. Soon, the collection grew beyond nostalgia. I sought out titles I had only glimpsed at friends’ houses, and even the ones I had read about in the glossy pages of British magazines.

What began as a personal pursuit became something larger. A fascination not just with the games themselves, but with the history behind them, the developers, the machines, the ideas that fueled them. I realized that these weren’t just toys or diversions; they were artifacts of an industry that, within my lifetime, had grown into the largest entertainment medium on Earth. For me, they remain doorways into stories, into history, into imagination. Into my own past.

This blog has, for well over a decade, been a sacred place for me. A space apart from the demands of adult life, from the conflicts raging across the globe, and from an internet that, once so full of promise, has been taken over by multi-billion-dollar corporations and now often feels like a vast dumping ground for the worst of human nature.

Thanks for reading and thanks for visiting!

A small part of my collection, on display at my home office.

Photo from 2023.

Your story is very familiar, right down to having a father who worked at IBM! (My Dad worked there for pretty much his entire professional career, before going into self-employed consulting after early retirement. He, too, worked with early systems such as the famous “WITCH”, aka the Harwell Computer.)

Our family also was immersed in home computing technology almost from its inception. Our machines of choice at home were the Atari 8-bit and ST, before making the (mostly) full-time switch to MS-DOS and Windows PC (including several IBM systems, of course) around 1992 or so. The ST still got plenty of use for MIDI purposes for quite some time after that, though.

My own online outlets (a few blogs and a YouTube channel) have likewise become a haven from the rest of the Internet, which I feel less and less keen on spending any time with by the day. And I, too, surround myself with shelves full of software that has consistently brought me joy from childhood in the ’80s right up until today. As I type this, I sit in front of a wall filled with Atari ST games, and I wouldn’t have it any other way.

Thanks for all your posts, which are a consistently fascinating read.

Thank you so much, Peter. I love hearing stories like that, thanks for sharing.

What beautiful legacy and story – thank you for sharing! And lovely to see those gold boxes displayed so prominently!

Thank you so much, Laszlo. I thought it was time to share something personal (I always write fully objectively). Glad you enjoyed it. And yes, those gold boxes deserves the very best:)

Thanks for sharing a piece of your Life. There are a lot of stories like yours, but this one is yours and it’s fantastic!

Thank you for those kind words!

Thank you so much for sharing your story! It was very inspiration, especially as a father myself. My girls see my office as some magical wonderland of videogames and technology. I have slowly been removing things, but now that I read your story, perhaps I should make it into a retro tech space for us to share. Thank you :)

Thanks, Yazid. Nothing is better than sharing and inspiring our kids:) United, we keep retro tech and games alive for the next generation.

As a game collector (and player) who, like you, finds refuge in his gameroom and reminds him of his youth, I enjoyed reading your story very much. It must have been awesome having a dad with such an affinity for technology. My dad has never been interested in computers and gaming. But I’m blessed because I can now happily share my love for gaming with my kids.

Thank you for sharing your story!

Your kids are very lucky! – thanks for sharing:)