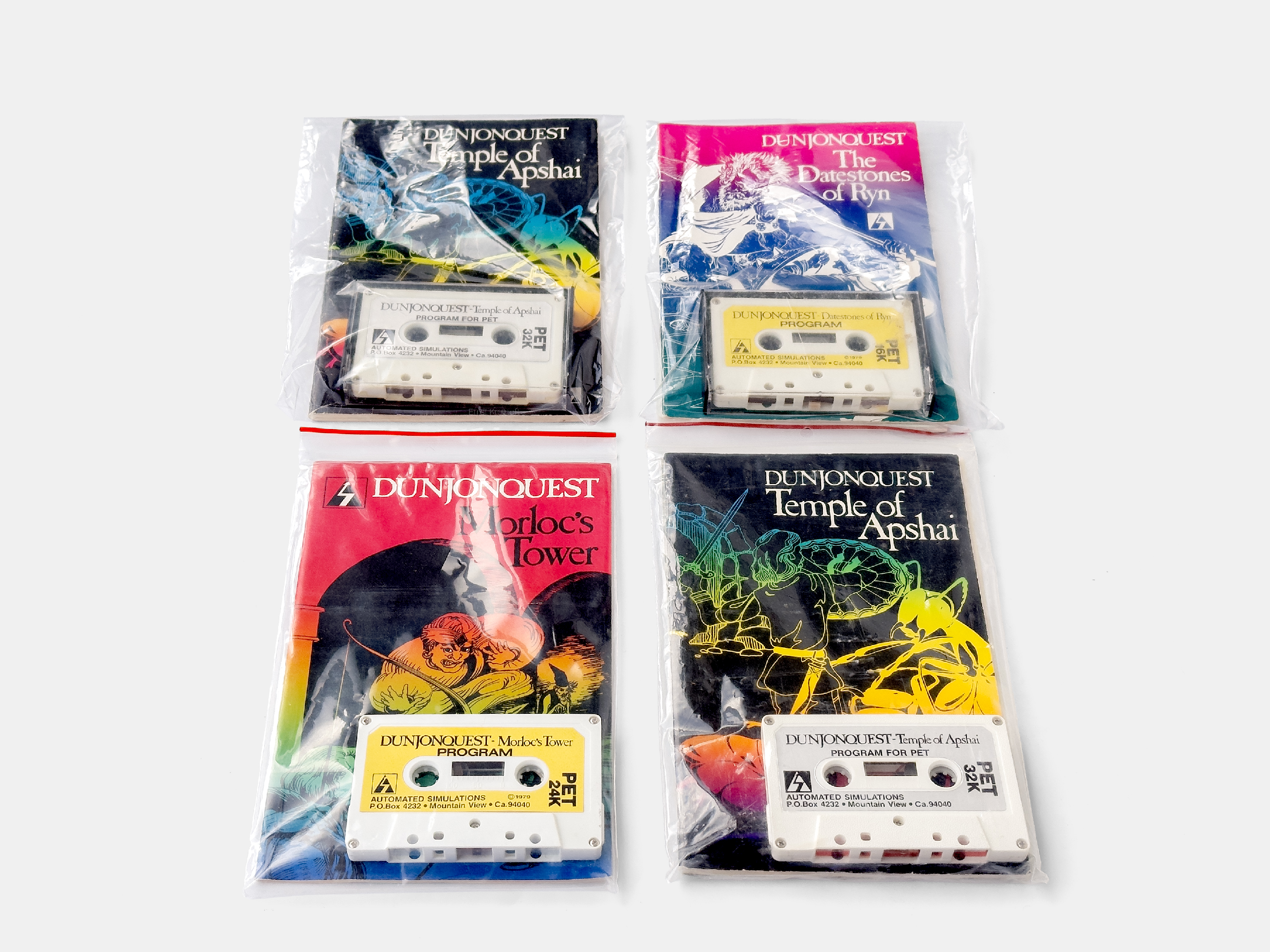

In the late 1970s, with the home computer industry still in its infancy, much of the software being written was aimed at hobbyists and technically minded players. In 1978, Jon Freeman and Jim Connelly founded Automated Simulations, one of the earliest independent computer game publishers. The debut, Starfleet Orion, was essentially a computerized board game, a turn-based space strategy designed to appeal to the same audience that played Avalon Hill war games. The following year, Temple of Apshai introduced role-playing mechanics and dungeon exploration, effectively translating the spirit of Dungeons & Dragons onto the screen. These early titles were intricate and rule-heavy, unapologetically aimed at the intellectually minded, simulation-oriented player.

Early Automated Simulations titles, ranging from 1978 to 1980.

These computer-based strategy and role-playing games helped establish the company as one of the first independent publishers in the home-computer market.

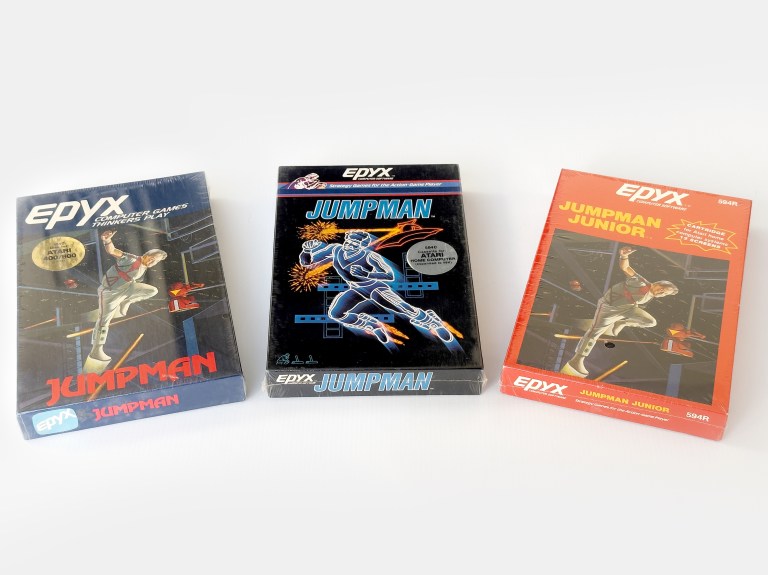

As the industry grew, so did the audience. By 1983, gone were both Freeman and Connelly, and Automated Simulations had rebranded itself as Epyx, a name that sounded sleeker and more in tune with the new arcade generation (the Epyx name had been used since 1980). Where Automated Simulations had been about digital rulesets, Epyx was about energy, color, and fun. The first major hit under the new name came in 1983 with Randy Glover‘s Jumpman, a game that spoke directly to the mainstream with its fast, arcade-style action designed to rival the coin-ops. The company quickly gained a reputation for slick, accessible titles and soon became one of the strong third-party publishers for the Atari 8-bit and Commodore 64, the era’s dominant home computers for gamers. Titles like Summer Games and Impossible Mission were polished, visually impressive, and created with a sense of style that matched the arcade cabinets teenagers flocked to at the mall.

After Epyx’s management change and repositioning in 1983, the company looked to expand beyond its original concepts. Under the guidance of Michael Katz, who had worked in product marketing at Mattel and later served as vice president of marketing at Coleco, Epyx found a new direction. Katz’s impressive resume provided both a working knowledge of retail audiences and an index of industry contacts that would prove decisive.

Randy Glover’s Jumpman from 1983 marked Epyx’s breakthrough into the mainstream.

Moving away from its early simulation roots, the company found success with the fast, colorful platformer, perfectly timed for the arcade-driven home-computer market of the early 1980s.

By the mid-1980s, G.I. Joe was everywhere in American pop culture. Hasbro had relaunched the line in 1982 as G.I. Joe: A Real American Hero, transforming the original 1960s soldier dolls into a line of action figures with vehicles, playsets, and a fictional universe. Each figure came with a “file card” that gave the character a backstory, a clever touch developed with input from Marvel Comics writer Larry Hama. Marvel itself carried the narrative further in its monthly G.I. Joe comic, which ran for over a decade and gave the brand depth and continuity. On television, the syndicated G.I. Joe animated series turned the characters into larger-than-life personalities, bringing Cobras and Joes into living rooms across the country.

Marvel’s G.I. Joe: A Real American Hero #1 from 1982.

The long-running comic book series gave the toy line rich backstories and helped cement G.I. Joe’s place in 1980s pop culture.

The G.I. Joe VAMP (Multi-Purpose Attack Vehicle), released in 1982.

Hasbro’s vehicles and playsets were central to the toy line’s appeal, designed with rugged, military-inspired detail that carried over into the computer game’s roster of recognizable hardware.

Image from eBay.

Hasbro’s strategy worked. Between 1982 and 1986, G.I. Joe became one of the most successful toy lines of the decade, rivaling Mattel’s He-Man and Kenner’s Star Wars toys. While Katz left Epyx in 1984, after being hired away by Atari Corporation as their President of the Entertainment Electronics Division, he had managed to leverage his industry ties and strike deals with both Hasbro and Mattel. For a publisher like Epyx, securing the license meant instant visibility with an audience that was both toy-buying children and computer-savvy teens.

With the agreement with Hasbro in place, the task fell to Epyx’s internal designers to transform the brand into a playable experience. The project was led by Ray Carpenter, who brought experience in arcade-style action design, working alongside Jeff Johannigman, a new arrival at Epyx. The challenge was how to take a toy line with dozens of characters and vehicles and distill it into something that could work on an 8-bit computer. Rather than attempt a sprawling narrative, Carpenter and Johannigman focused on delivering combat-driven gameplay that spotlighted familiar faces and hardware from the toy shelves.

Development of the Commodore 64 version was primarily handled in-house at Epyx, but the Apple II version was contracted to K-Byte, a small but prolific development house based in California. Founded in the early 1980s, K-Byte had established itself as a reliable partner for publishers who needed quick, competent conversions to the Apple II. The company was credited on numerous ports during the period, including several Epyx titles, and had a reputation for making the most of Apple’s dated graphics and sound.

While the Apple II remained a significant platform in schools and among long-time owners, it was showing its age next to the Commodore 64’s superior sprites, color palette, and SID sound chip. K-Byte’s task was to translate Epyx’s vision into a form that worked within the Apple II’s constraints, requiring clever compromises in color use, animation, and memory management.

G.I. Joe: A Real American Hero reached store shelves in 1985. Epyx marketed the game as part of its “Computer Activity Toys” line, alongside two other licensed titles, Hot Wheels and Barbie.

G.I. Joe: A Real American Hero was released for the Apple II and Commodore 64 under Epyx’s short-lived “Computer Activity Toys” banner in 1985.

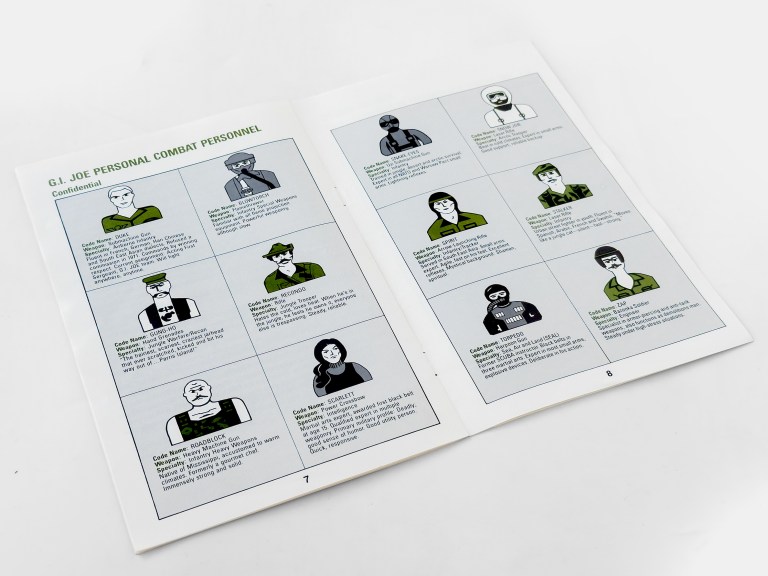

The game features 16 playable Joe characters, facing off against 8 Cobra villains across missions set around the world, from deserts and tundra to forests and cities. Players alternate between overhead vehicle-based assaults and one-on-one battles.

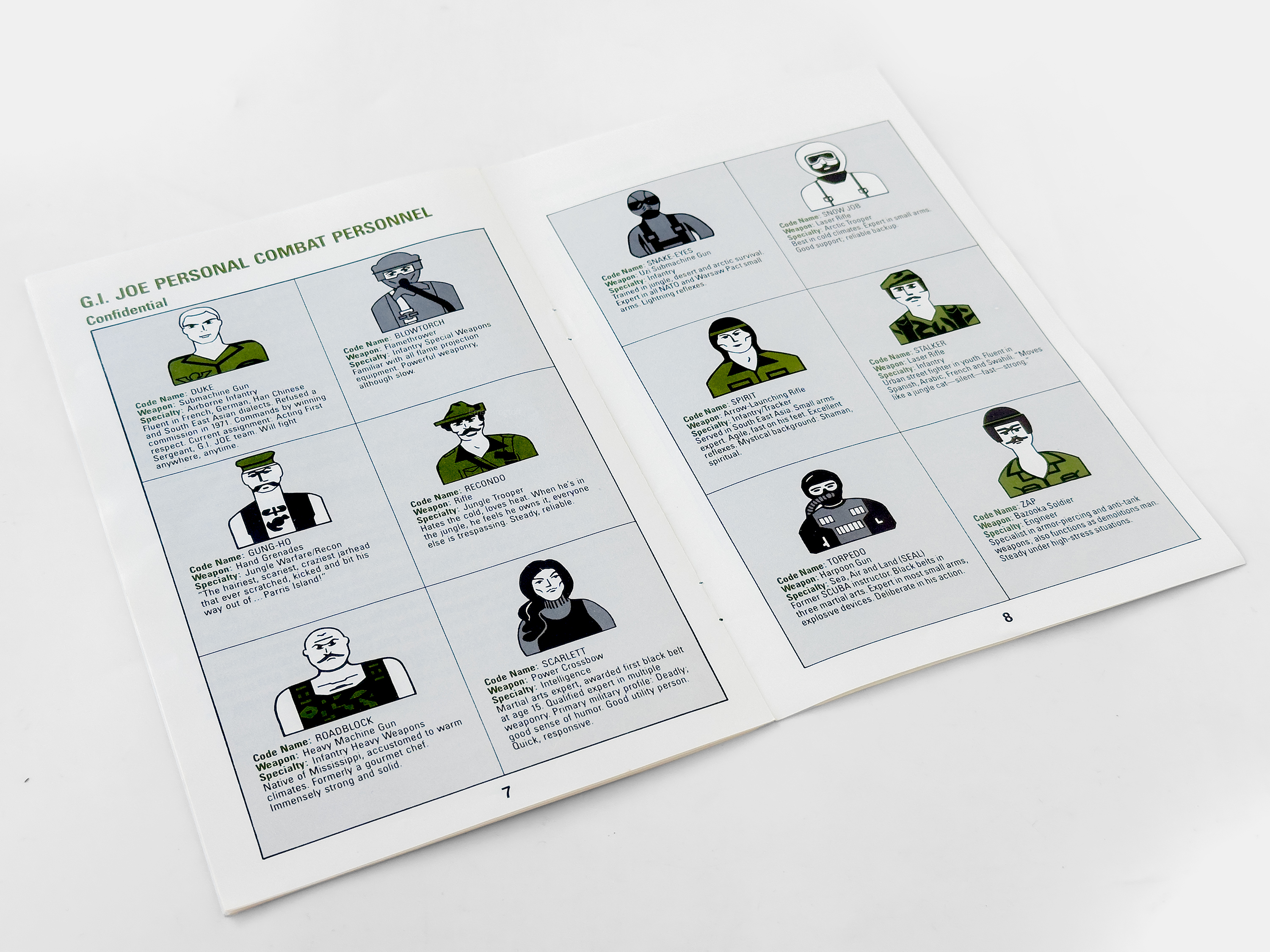

The 16 G.I. Joe characters and eight Cobra villains are each described in the manual.

The Commodore 64 version was widely considered the stronger release. The system’s superior graphics and sound gave the game more punch, with colorful sprites and satisfying effects that matched Epyx’s usual high standards. On the Apple II, however, compromises were evident. The hardware’s limited color palette and slower animation meant the action felt less fluid, and the audio was more primitive.

The disparity reflected a broader truth about the mid-1980s computer market. By 1985, the Apple II was nearly a decade old, and while still present in classrooms and loyal homes, it struggled against newer, cheaper, and more powerful machines. The Commodore 64, priced aggressively and marketed directly to gamers, became the preferred platform for action titles like G.I. Joe.

G.I. Joe was met with curiosity when it hit shelves in 1985. Reviews in magazines such as Commodore Power/Play and Compute!’s Gazette noted the appeal of the license and the variety of characters, but some critics found the gameplay repetitive. The lack of a larger narrative or mission structure left the game feeling more like a straightforward action title than an epic battle between the G.I.s and Cobra. Still, for fans of the toys and cartoon, the chance to play as their favorite characters was enough to make the game appealing.

The Apple II version received a more muted response. Even Apple-focused publications acknowledged that it lacked the polish of the Commodore release. By that time, the system’s technical limitations made it difficult to impress in an era when players were increasingly accustomed to smooth scrolling, vibrant colors, and layered soundtracks. Despite the shortcomings, G.I. Joe sold respectably, benefiting from the brand’s visibility and Epyx’s strong distribution.

G.I. Joe: A Real American Hero was less about breaking new ground and more about capturing a cultural (and financial) moment, borrowing the excitement of Saturday morning cartoons and toy aisles and translating it onto screens across the nation. While the game never reached the iconic status of Epyx’s sports titles, for kids who were already staging battles on bedroom floors with plastic figures and vehicles, it offered a new, exciting way into the universe.

Sources: Wikipedia, MobyGanes, yojoe.com, Time Extension…

Your lot of the first Automated Simulations games is impressive. I was looking for the PET versions, but have yet to see any PET releases in baggie or box. Seen the single tapes for sale, but the price was early way too high for my limited budget :) Probably due to low sales, there are very few out there.

I got a couple PET versions of their first games, released by Commodore Europe, just single tape and sparse text inlays. Not sure if theirs came with manuals, but mine did not.

Thanks. Yeah, the original PET releases are quite ellusive. I have a few (see the attached photo) but are still actively looking for the ones I’m missing.

I’m not sure how these were released in Europe but usually European releases were quite sparse in scale.

I got the Commodore UK version of Datestones of Ryn, on tape, sold by Sumlock Mondain (in Norwich). Just Commodore UK PET generic branded inlay, with stamped title on the cassette label. Not as elegant as the US versions, and probably cheaper.