In 1981, Atari launched the Atari Program Exchange, APX, an unusual experiment that invited hobbyists to submit original programs for possible publication. It was part catalog, part competition. Atari would distribute promising submissions, pay royalties to the authors, and award an annual Star Award to spotlight the most innovative work.

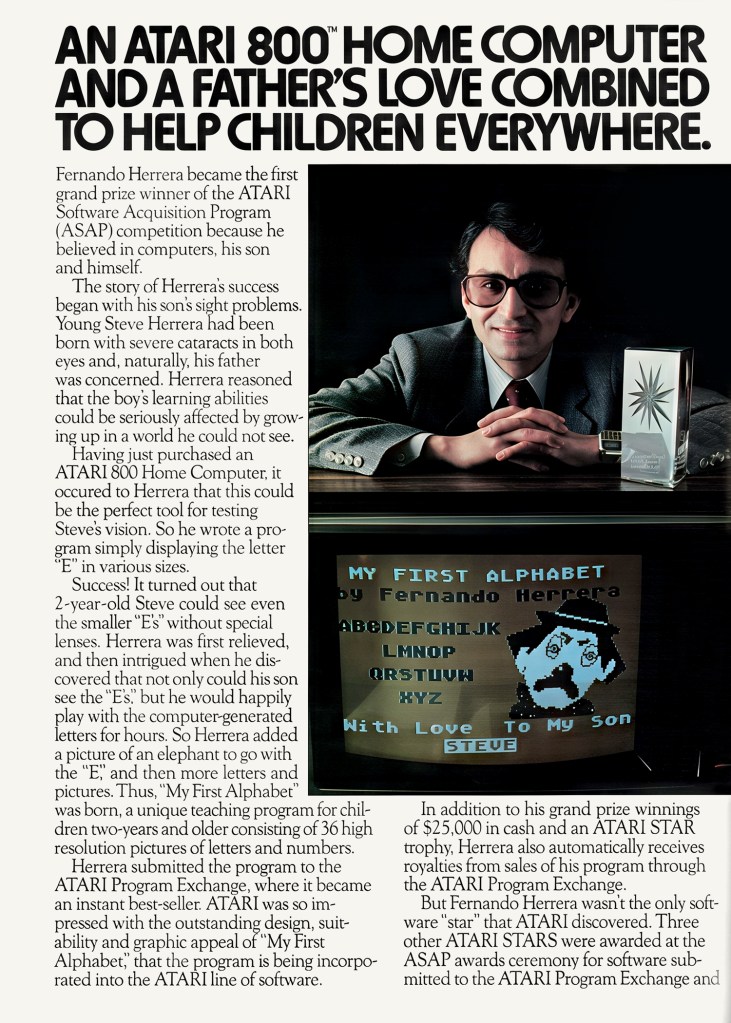

The very first Star Award, carrying a $25,000 prize, went to Fernando Herrera, a Colombian-born architect who had only recently discovered computers. His entry, My First Alphabet, was deeply personal, a program designed to help his young son learn to recognize letters despite a severe visual impairment. The program became an instant APX bestseller, and the recognition transformed Herrera from a hobbyist into a rising figure in the fast-growing home-computer industry.

Herrera’s path to computing had been anything but conventional. Born in Bogotá in 1942, he showed artistic talent from an early age, drawing, painting, and shooting his own 8mm films as a child. After earning a degree in architecture from the National University of Colombia, he moved to the United States in 1970. Here he worked as an industrial engineer in the steel industry, competed in U.S.C.F. chess tournaments, and only stumbled into computers around 1979, after spotting a newspaper ad for a “home computer.” At the time, his only concept of a computer came from HAL in Stanley Kubrick‘s 2001: A Space Odyssey. Curious, he began devouring books and magazines, teaching himself programming on paper before he ever touched a machine.

By 1980, Herrera had saved enough to order an Atari 800 through the mail, a $2,500 purchase. The first program he typed in was the chess game he had written by hand months earlier. To his amazement, it ran flawlessly on the first try. Soon, the Atari became not only his obsession but also a tool to connect with his son. Remembering eye tests at the doctor’s office, Herrera displayed large spinning letters on the screen, testing how well his son could recognize them. The experiment gradually expanded into a full educational program, with music, colors, and images — My First Alphabet.

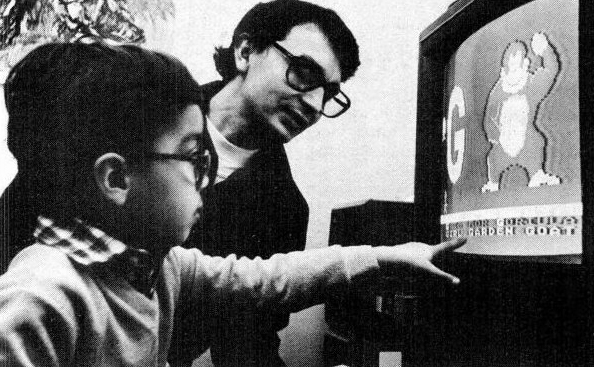

An article in BYTE magazine, May 1982, chronicled Fernando Herrera’s journey with My First Alphabet.

The feature highlighted how a father’s solution for his son’s visual impairment won Atari’s inaugural Star Award, showcased the promise of the Atari Program Exchange, and introduced Herrera to the wider computing world.

Picture from Byte Magazine

Fernando Herrera, with his young son, Steven, exploring My First Alphabet.

What began as a father’s attempt to help his visually impaired child became a small milestone in early home-computer software. The program’s warmth and accessibility stood out in a market dominated by games and utilities, earning Herrera the very first Atari Star Award and setting him on a new career path.

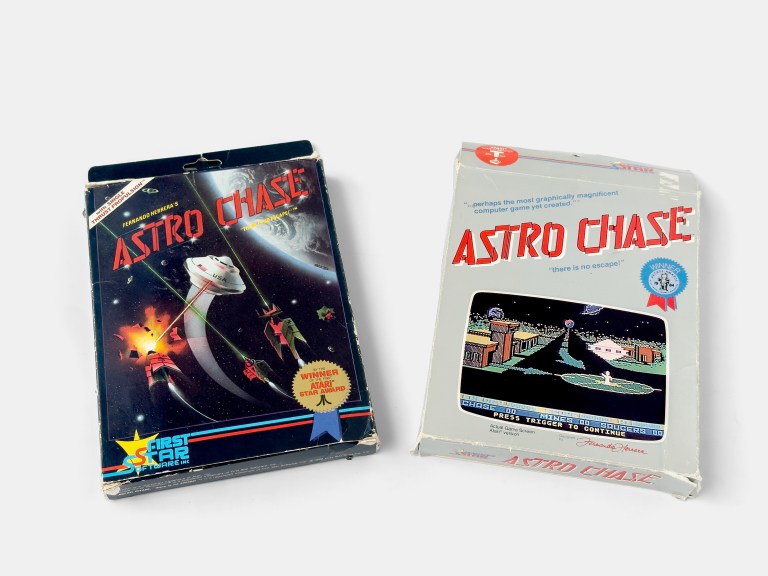

Picture from The American Classic Arcade Museum

Around the same time, Herrera began creating simple amusements. A dot-chasing exercise to help his son master the joystick evolved into his first game, Space Chase, written in Atari BASIC. The game was published in 1981 by Swifty Software, run by schoolteacher Lee Jackson, a key figure in the New York Atari user-group scene. The game was so well-written that one Electronic Magazine reviewer assumed it had been coded in assembly language. Herrera followed it with another game, Time Bomb, and even sold a BASIC line-renumbering utility through classified ads, his first taste of the wider software market. Magazine reviews and articles eventually caught the attention of two New York film producers and entrepreneurs, Richard M. Spitalny and William Blake.

Spitalny had a background in media and distribution. He had already produced films and shown an instinct for spotting creative properties with commercial potential. Blake, similarly tied to the New York independent film and television scene, shared Spitalny’s interest in storytelling and entertainment ventures. When they contacted Herrera in 1982, the pair initially proposed that he manage a computer retail store on Long Island, which they would finance. Though the shop did well, it quickly became clear Herrera’s real passion was programming. Spitalny and Blake encouraged him to write a business plan for a software company instead. Unfamiliar with formal business planning, Herrera arrived at their Manhattan office with a handful of handwritten index cards outlining his ideas. To his surprise, the producers, frustrated with the difficulties of raising millions for film projects, agreed to bankroll the venture.

The result was First Star Software, founded later that year. Herrera supplied the creative spark and technical skill, while Spitalny and Blake handled the financing, marketing, and distribution. The name was a nod to Herrera’s Atari Star Award, and he even designed the company’s logo. First Star’s philosophy was simple but ambitious: create imaginative, visually striking games with distinctive sound, adaptable to multiple platforms, and strong enough to license widely. Peter Jablon joined in an executive capacity, providing business stability during the company’s early growth.

Money came quickly at first. Herrera later recalled being both elated and bewildered as his partners funded the fledgling studio out of their own pockets when promised outside capital never appeared. In June 1982, they took him to the Summer Consumer Electronics Show in Chicago, introducing him as the “Atari Star Award winner” in meetings with industry heavyweights, including a young Trip Hawkins of newly formed Electronic Arts. Herrera, still green as a programmer, sometimes felt like a prop, but the exposure put First Star in front of the industry’s elite.

Summer Consumer Electronics Show, Chicago, June 1982.

Widely regarded by attendees as the “Summer Video Games Show,” the event overflowed with new consoles, cartridges, and arcade conversions, reflecting the industry’s booming confidence. Video games were the cultural phenomenon of the moment, seemingly unstoppable, but within eighteen months, the market would collapse in one of the most dramatic downturns in entertainment history.

Picture from Wikipedia.

Back home, Herrera faced the daunting task of actually producing a commercial game worthy of the buzz. He had toyed with ideas sketched out on scraps of paper, including one project called Dangerous Cargo that never materialized. Instead, he returned to an earlier space-themed prototype and began what would become Astro Chase. The project forced a pivotal decision of whether to stay in BASIC, his comfort zone, or attempt machine language, which he barely understood. Determined to realize his vision, he taught himself assembly from scratch, creating everything without libraries or prewritten functions. By November 1982, after months of struggle, First Star’s debut game was complete.

When the game premiered at CES in Las Vegas in January 1983, First Star’s booth happened to face the main escalators. A giant screen showing the colorful and ambitious space shooter that combined arcade action with cinematic cut-scenes and an innovative control scheme ensured that attendees couldn’t miss it. Crowds gathered, and the buzz made Astro Chase one of the show’s highlights.

Winter Consumer Electronics Show, Las Vegas, January 1983.

It was here that First Star Software unveiled Astro Chase, introducing Fernando Herrera’s ambitious debut to buyers and the press. CES had quickly become the launchpad for home computer and video game titles, with Atari, Commodore, and a host of publishers vying for attention. For Herrera, who had only two years earlier been a hobbyist submitting programs to Atari’s APX catalog, the event marked a dramatic leap into the spotlight of the booming games industry.

Picture from LVCVA Archive, Las Vegas News Bureau Collection.

Fernando Herrera’s Astro Chase, released in 1982, was the debut title from First Star Software. The game’s striking visuals and ambitious design helped establish the company as a serious new player in the rapidly expanding home-computer market.

Astro Chase featured striking visuals and an innovative control scheme. Instead of guiding a ship across a static starfield, the player’s craft was fixed at the center while planets, enemies, and terrain scrolled dynamically around it. Between levels, small animated cut-scenes, astronauts rescued or cheered by parading crowds, added a rare touch of cinematic storytelling for the era, fitting neatly with Spitalny and Blake’s background in film production.

Astro Chase drew critical acclaim, won Electronic Games’ Arkie Award for Best Science Fiction/Fantasy Computer Game. Parker Brothers licensed it for the ColecoVision and Atari 5200 with a $250,000 advance, thus securing the future for the young company. In 1984, Exidy brought it into arcades, along with three other First Star titles, through its Max‑A‑Flex system, basically, an arcade cabinet with an Atari 600XL inside.

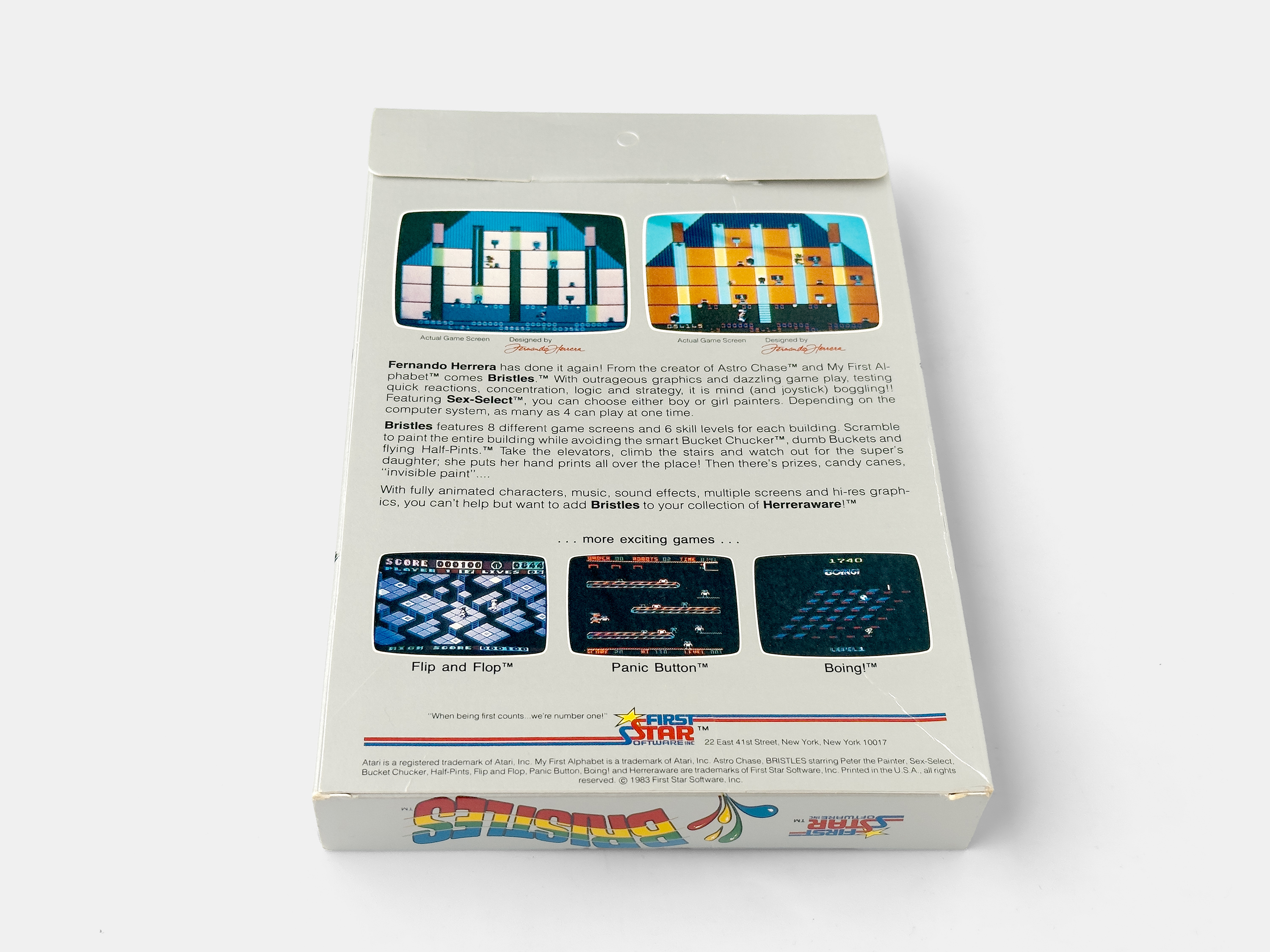

The early 1980s were full of arcade-inspired experiments. Amidar had players “painting” the screen, while BurgerTime turned cooking into platforming chaos. Herrera took a similar approach for his follow-up, Bristles, transforming the mundane act of house painting into a whimsical yet challenging game.

Herrera’s architectural training shaped his design. Levels were structured like compact blueprints, with ladders, elevators, and layers forming each house. Brushes acted as lives, earned back at the end of a house. What truly set the game apart, however, was its soundtrack. Playful snippets of Tchaikovsky’s Nutcracker stitched into the action, turning pratfalls into comic stings and gameplay into performance.

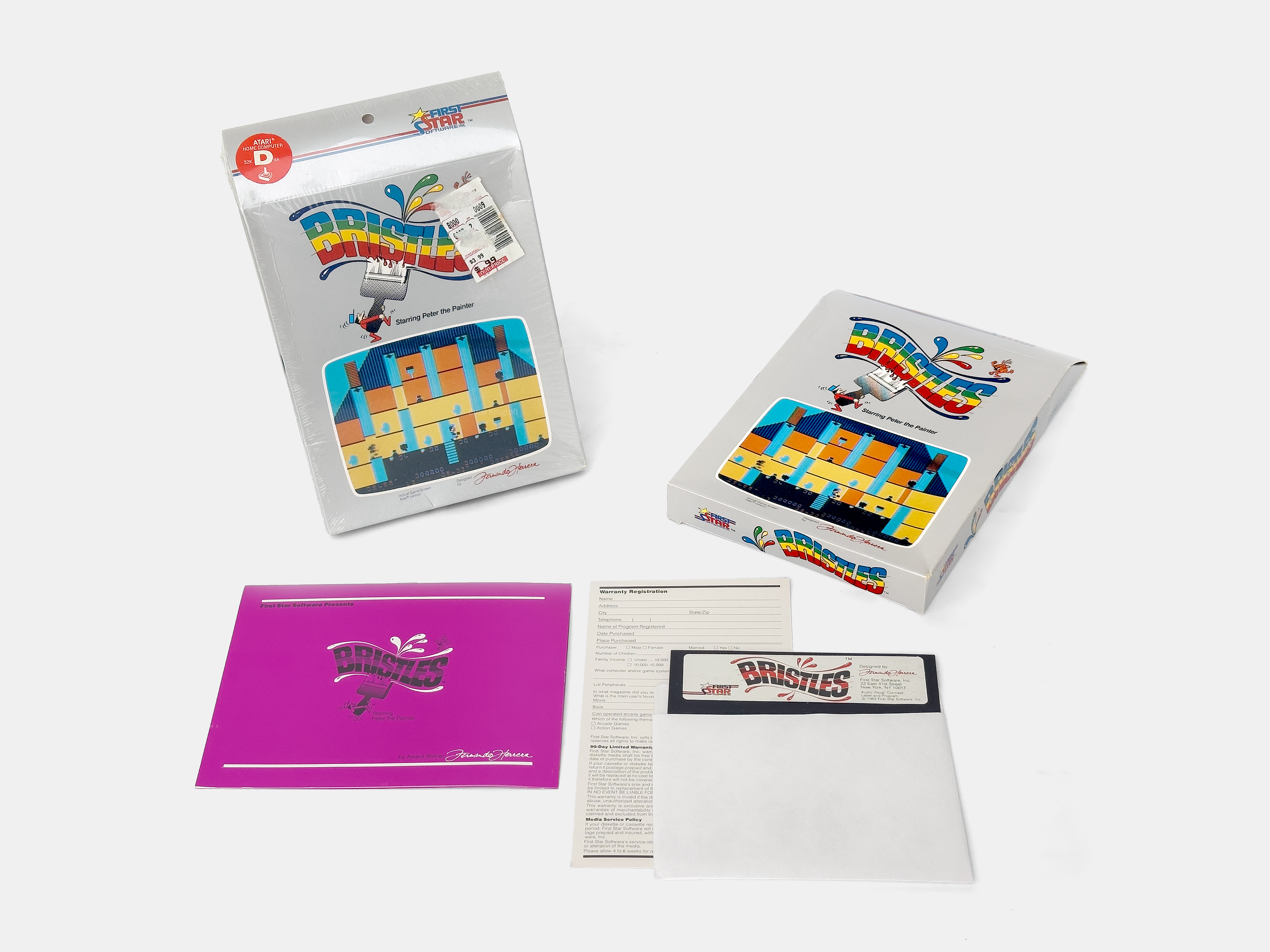

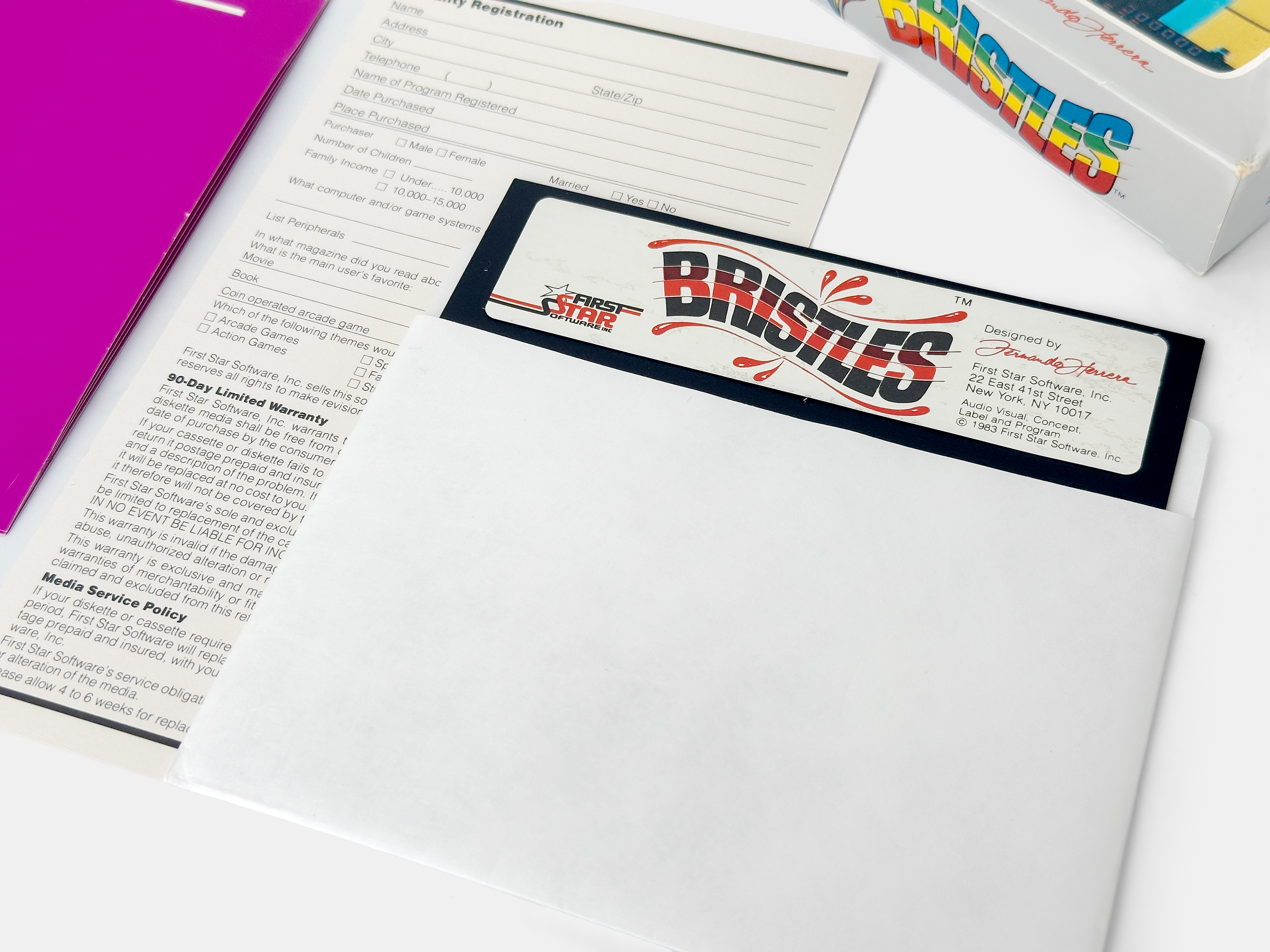

First Star shipped Bristles for the Atari 8-bit and Commodore 64 in 1983, with the C64 port handled by Adam Bellin. As with Astro Chase, the company licensed an arcade adaptation for Exidy’s Max‑A‑Flex system.

Fernando Herrera’s Bristles, released in 1983, was his second title for First Star Software. Lighthearted and whimsical, it transformed the everyday task of house painting into a frantic platform challenge.

Players step into the shoes of Peter the Painter, racing to finish eight houses before brushes and time run out. Hazards are all around with the sly Bucket Chucker, tumbling paint cans, and the superintendent’s daughter leaving handprints everywhere, forcing constant improvisation. Most of its unique charm was the soundtrack, stitched from Tchaikovsky’s Nutcracker, with every slip and stumble punctuated by a comic musical sting. On Atari systems, up to four players could enjoy it.

Reviewers praised its vibrancy and originality. Antic Magazine highlighted the fast action and novel challenges. Video Games magazine pointed to the music as the star. GAMES called it a “charmer,” while warning of its chaotic pace. Later, ANALOG Computing revisited the game, noting its difficulty, demanding, but fair with practice.

While Bristles never became a flagship title, it showcased the humor, rhythm, and adaptability that would define First Star’s catalog. The arcade version added a curious footnote, and in the 2000s, an authorized Atari 5200 cartridge release revived interest among collectors.

First Star’s true breakthrough came in 1984, with the release of Boulder Dash, developed by Peter Liepa, which became an enduring multi-million-selling franchise. Through the mid-1980s, the studio also handled hits like Spy vs. Spy, expanding largely by licensing its catalog across platforms worldwide. In later years, First Star focused on leveraging its strongest brands, particularly Boulder Dash, through ports, remakes, and licensing deals.

For Herrera, though, the rapid evolution of the industry was exhausting. “The technology is changing, the level of gaming keeps changing,” he later reflected. By 1988–89, he stepped back, remaining a silent partner at First Star but turning his focus to more practical software.

What began with small database applications for doctors and lawyers grew into large contracts, including a marketing-analysis system for AT&T that ran on personal computers rather than mainframes. AT&T even offered him a permanent position, which he declined, preferring the independence of consulting. Over the following decade, he reinvented himself multiple times, working in banking, mortgage software, real estate systems, and eventually online marketing.

In 2018, First Star’s catalog was acquired by German publisher and developer BBG Entertainment, ensuring that above all, Boulder Dash remained available on modern platforms. Herrera, meanwhile, stepped further out of the spotlight. His final credited game, Astro Chase 3D for the Macintosh in 1994, won critical praise, a fitting epilogue for the unlikely programmer who had started with a Star Award, some index cards, and a strong vision of what small, characterful games could be.

Sources: The Atari 8-Bit Podcast interview with Mr. Herrera, computingpioneers.com, Wikipedia, Electronic Games Magazine, Compute!, The Golden Age Arcade Historian…

Great publisher. I got all of their first releases, except the one I want the most, Boulderdash. I got it from Micro fun, but that was a re-release, I think.

Great pulisher and great games:) and yes, the original Boulderdash was released by First Star.

You know what the connection to Micro Fun publisher was about? First Star licensed out Boulderdash titles to them? Micro Fun had the original Dino Eggs.

I’m not sure. First Star was primarily interested in Atari and would often license its titles to third-party publishers. Many small publishers/developers of the time (which First Star definitely was) licensed ports of titles to other companies that had the expertise and means to port and distribute them quickly and efficiently. Titles usually only had a few months of shelf life before being replaced… I think I read somewhere that Micro Lab (Micro Fun) paid somewhere around $1.1-1.3 million for the right to Boulderdash.