‘Let us therefore brace ourselves to our duty and so bear ourselves that if the British Empire and its Commonwealth lasts for a thousand years, men will still say, “This was their finest hour”’ – Winston Churchill, 1940

In the summer of 1940, the world watched as the skies over Britain became the stage for one of history’s most dramatic and defining aerial campaigns. The German Luftwaffe, having steamrolled through Europe, now sought to break the will of the British people by gaining air superiority. But against overwhelming odds, from July to September 1940, the Royal Air Force stood firm, engaging in a relentless fight for control of the skies, one that would ultimately determine the fate of Britain. Outnumbered but determined, the Spitfires, Hurricanes, and the brave pilots of the Royal Air Force proved that Hitler’s seemingly unstoppable war machine could, in fact, be stopped.

For decades, the clash of fighter aces and bomber formations has fascinated historians, writers, and filmmakers alike. Its combination of high-stakes aerial combat and acts of extraordinary courage made it a perfect subject for storytelling across every medium, from books and films to television and, eventually, video games.

When 19-year-old Lawrence Holland graduated from Cornell University in 1978 with a degree in Anthropology and Prehistoric Archaeology, game development wasn’t even a blip on the radar. His early career followed an academic path, fieldwork on archaeological digs across Africa, Europe, and India, but the trajectory changed dramatically in 1981 when he moved to California to pursue a doctorate at UC Berkeley.

Instead of enrolling in graduate school, Holland found himself drawn to a different kind of education, one delivered not in classrooms but through the bits and bytes of the Atari 800 computer his roommate had brought home. What started as a passing curiosity quickly became a consuming passion. By 1982, Holland had acquired one of the first Commodore 64s off the production line. He taught himself assembly language, took programming courses, and before long, his skills were on par with seasoned professionals.

In early 1983, he landed his first job in the industry at Human Engineered Software, better known as HESware, a company focused on bringing the arcade experience into living rooms across America. The company briefly became home to another rising star when a young Ron Gilbert joined the company in 1984. But the timing was unfortunate. As the home computer market wobbled under the weight of oversaturation and economic uncertainty, HESware collapsed and filed for bankruptcy in late 1984. The company’s assets were acquired by Avant-Garde Publishing, which attempted to revive its development pipeline. One of Holland’s final contributions under the HESware banner was Project: Space Station, a simulation game for the Commodore 64 released in 1985. By this point, Holland’s talent for simulation and design was undeniable.

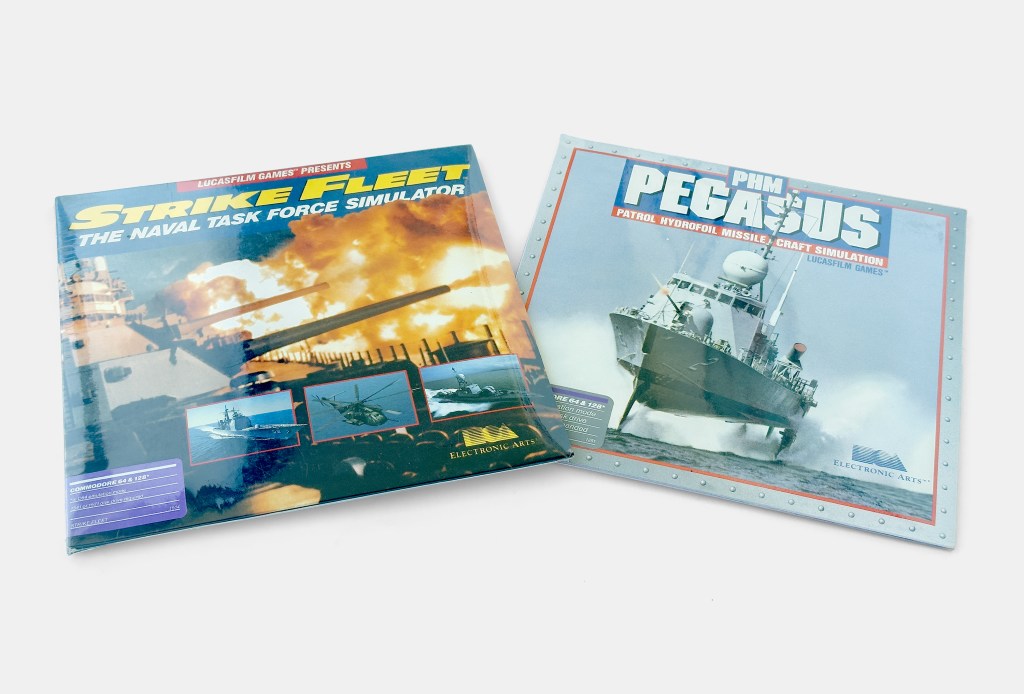

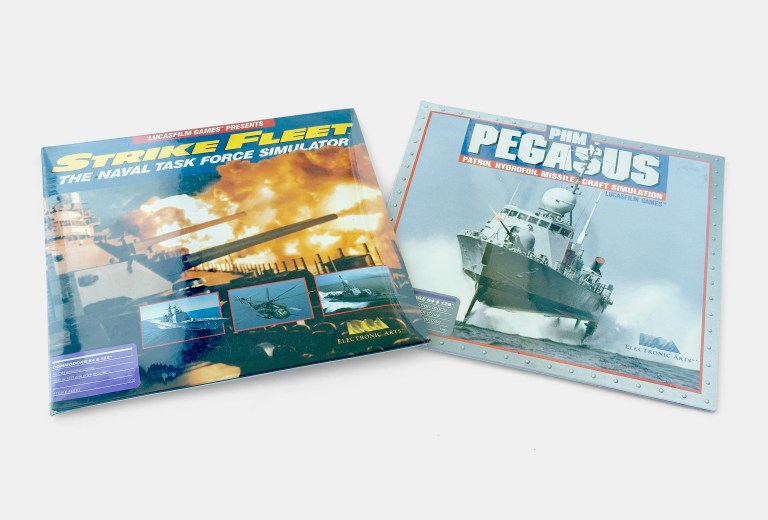

Following the collapse of HESware, both Holland and Gilbert found their way to George Lucas’s Skywalker Ranch, joining the Lucasfilm Games division, though in very different capacities. Gilbert was hired as an in-house game designer, eventually becoming a key figure in shaping the modern graphic adventure. Holland, by contrast, joined the studio as a freelance programmer with his first assignment being the port of the 1986 title PHM Pegasus to the Apple II. To the surprise of many, the fast-paced simulation of hydrofoil warfare, designed by Noah Falstein, became a best-seller, making it the first Lucasfilm Games title to sell over 100,000 copies.

Holland continued working with Lucasfilm Games as an external collaborator. The next project, Strike Fleet, developed under the direction of Falstein, was an unofficial sequel to PHM Pegasus, offering a broader and more strategic take on modern naval warfare. Serving as lead programmer, Holland helped shape Strike Fleet into a thoughtful evolution of the genre, solidifying his reputation as one of the go-to developers for military simulations that struck a fine balance between realism and playability.

Before his name became synonymous with WWII flight simulators, Lawrence Holland contributed to PHM Pegasus (1986) and Strike Fleet (1987) as an external contractor for Lucasfilm Games. The titles emphasized tactical realism and marked Holland’s early involvement with military-themed simulations

With the release of Strike Fleet in 1987, Holland was ready to leave the now-aging 8-bit Commodore 64 behind. The future was clearly shifting toward more powerful machines, and the IBM PC, rapidly becoming the platform of choice for serious gamers and developers alike, offered new possibilities. He soon pitched an ambitious new project to Lucasfilm Games. He wanted to create a World War II flight simulator, blending historical accuracy with cinematic flair and fast-paced aerial combat.

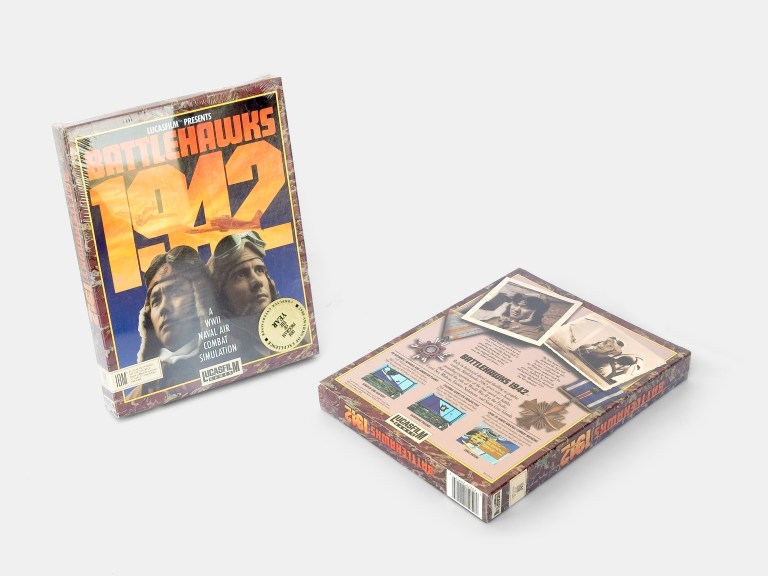

The project became Battlehawks 1942, a bold departure from the sterile, technically-minded flight sims that had defined the genre. Focusing on four pivotal naval air battles in the Pacific Theater, players engaged in aerial combat, learned tactics, aircraft behavior, and the strategic significance of each battle. The game drew widespread acclaim for its intuitive controls, gripping dogfights, and thoughtful historical framing. Critics highlighted its respect for the subject matter, while players appreciated how it made complex military history both accessible and thrilling. In 1989, Computer Gaming World named it Action Game of the Year, a clear sign that Holland’s approach had struck a chord. He had shown that flight simulators could be more than technical showcases.

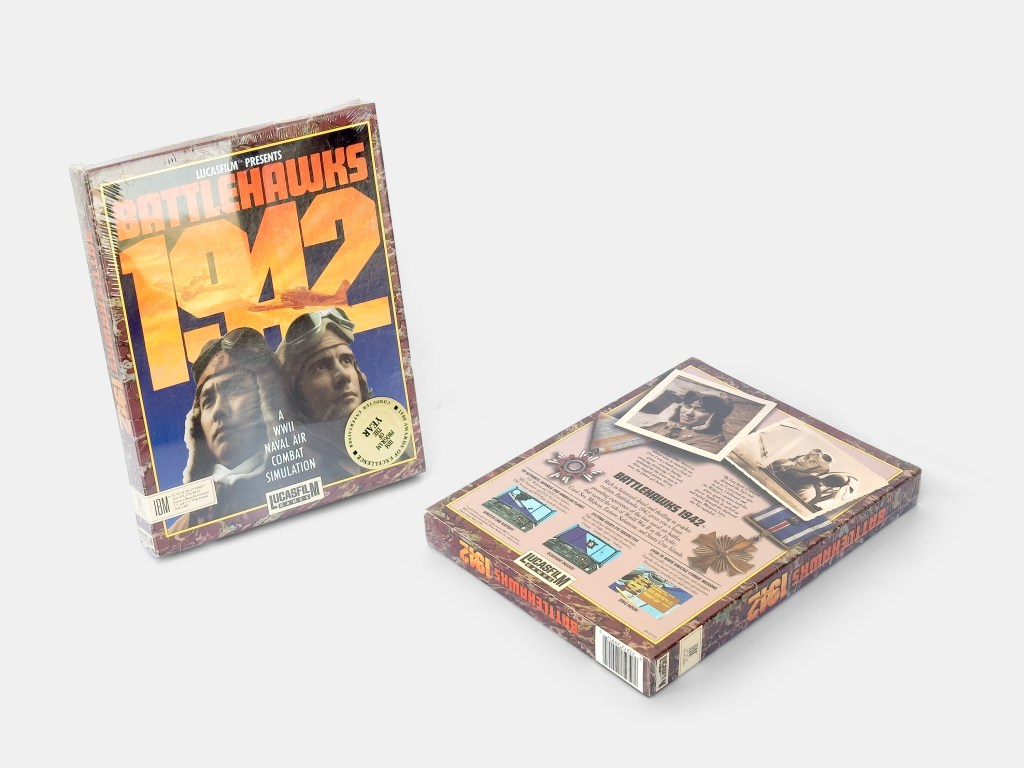

Battlehawks 1942, released in 1988, marked Lawrence Holland’s first foray into World War II air combat for Lucasfilm Games. The game focused on four pivotal naval air battles in the Pacific Theater and combined historical authenticity with accessible flight mechanics.

Building on the momentum, Holland turned his attention to a conflict that hit closer to home for many. The desperate battle for air superiority over England in that fateful summer of 1940. The Battle of Britain, not only a crucial turning point in World War II, but also the backdrop for one of the most stirring speeches in modern history. On 18 June 1940, just over a month after assuming the role of Prime Minister, Winston Churchill stood before the House of Commons and declared, “This was their finest hour.” A phrase heavy with defiance and resolve, a rallying cry for a nation under siege that would lend its name to Holland’s next game.

While Battlehawks focused on discrete air battles in the Pacific, Holland’s new project introduced a structured campaign mode that let players influence the broader course of the war. He was drawn to the campaign’s historical “what if” stakes, a moment in history that could truly have gone either way. This time, players wouldn’t just fly missions, they’d influence the course of history. At the heart was a structured campaign mode that simulated the turning tides of the pivotal 1940 air campaign.

A revamped game engine allowed for smoother flight dynamics and more detailed models, and now supported the Adlib sound card, allowing for more prominent engine noises and gunfire sounds. Internally, the team tested various engagement scales and found that the engine’s sweet spot was up to 16 planes on screen. Scenarios like four German bombers versus a dozen RAF defenders, or six British fighters against ten Luftwaffe aircraft, yielded the most thrilling and balanced combat.

On a strategic map, players could get an overview of the assigned mission, friendly and enemy squadrons’ location, heading, etc, and select which squadrons and planes to personally fly. The outcome of each mission had real consequences, affecting the status of the broader campaign. Victory for the British meant holding out long enough or destroying enough German aircraft. The German side, in turn, could win by grounding the RAF, eliminating enough British fighters either in the skies or on the ground.

The broader strategic layer was backed by a wide array of authentic aircraft. On the RAF side, players could take to the skies in the iconic Supermarine Spitfire or the rugged Hawker Hurricane. The Luftwaffe arsenal was more varied with the nimble Bf 109, the twin-engine Bf 110 heavy fighter, the dreaded Ju 87 Stuka dive bomber, and three bombers, the Dornier Do 17, Heinkel He 111, and Junkers Ju 88, all modeled with historically accurate flight behavior and armaments. In bombers, players could switch between flying, manning defensive guns, and handling the bombardier’s role.

The game included training missions for each aircraft as well as numerous historical scenarios, grounded in the actual tactics and objectives of the campaign. RAF missions leaned heavily toward defense, interceptions, and scrambles to protect British targets, while the Luftwaffe focused on bombing runs and fighter escort duties.

But perhaps most empowering for players was the addition of a built-in mission builder. For the first time, they could design their own scenarios from scratch, customizing objectives and enemy forces. Rounding out the experience was a robust film playback feature, allowing recorded flights to be reviewed, studied, and even shared, allowing players to perfect their skills or relive their greatest moments.

By the fall of 1989, Their Finest Hour: The Battle of Britain was ready for takeoff. Released for IBM PCs in October, it brought Holland’s cinematic, historically grounded vision to a rapidly expanding MS-DOS market. Ports for the Atari ST and Commodore Amiga followed in 1990.

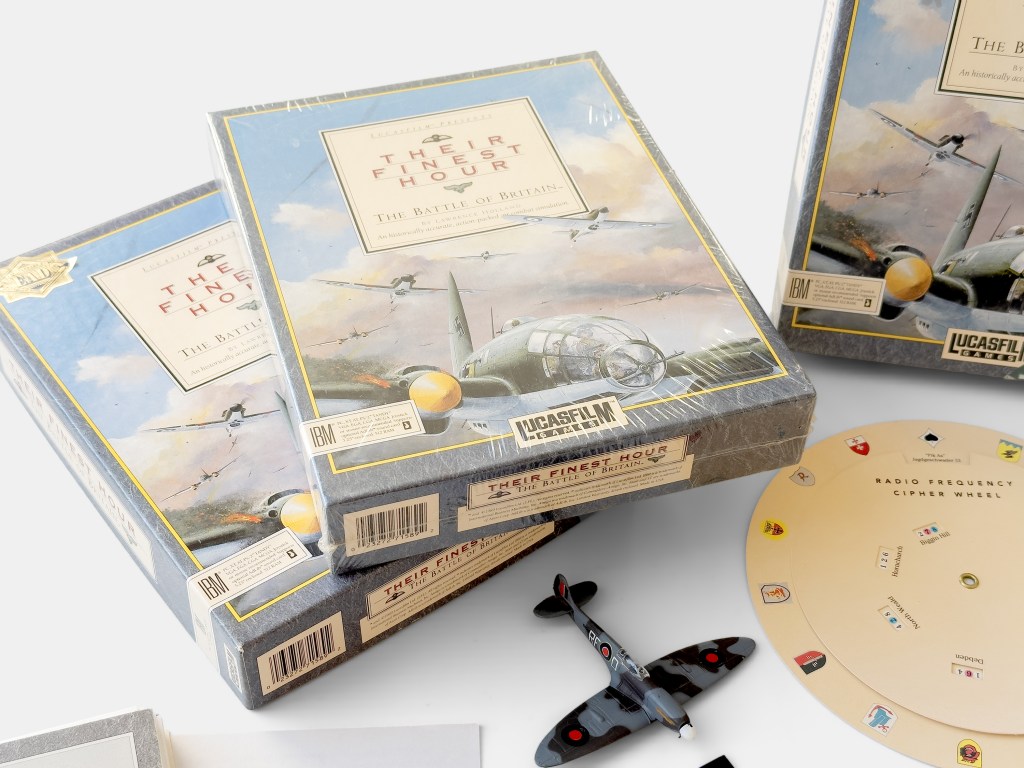

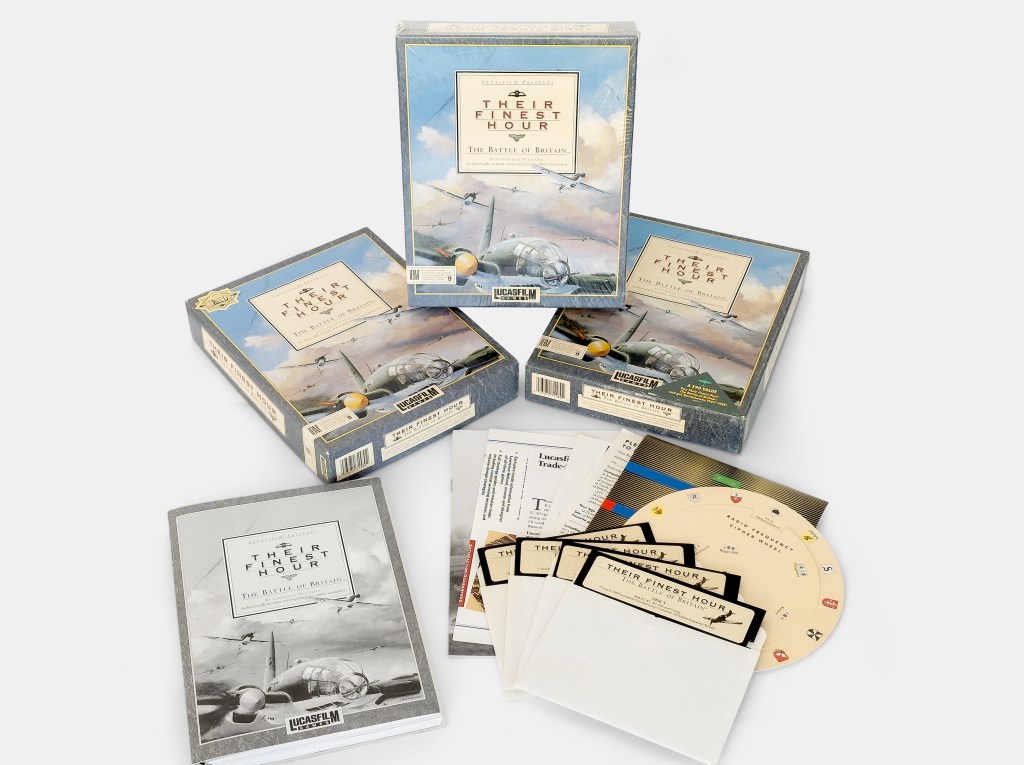

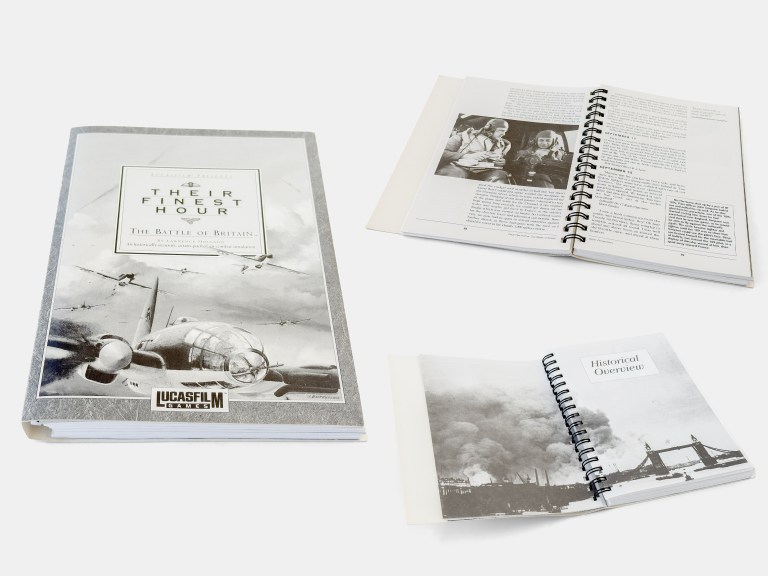

Their Finest Hour: The Battle of Britain, Lawrence Holland’s second World War II flight simulator, was released by Lucasfilm Games for the IBM PC in 1989. The box included a comprehensive 192-page manual, supplemental reference materials, four 5.25″ floppy disks, and a radio frequency code wheel used for in-game communication and copy protection.

The fantastic cover art was done by renowned British technical illustrator John Henry Batchelor, known for his meticulously detailed cutaways and military artwork.

Their Finest Hour: The Battle of Britain allowed players to fly for both the RAF and the Luftwaffe, taking part in pivotal missions across the summer of 1940. The game included several key aircraft and historical scenarios. For many players, this was their first introduction to the heroism and sacrifice of the RAF pilots who defended Britain against overwhelming odds.

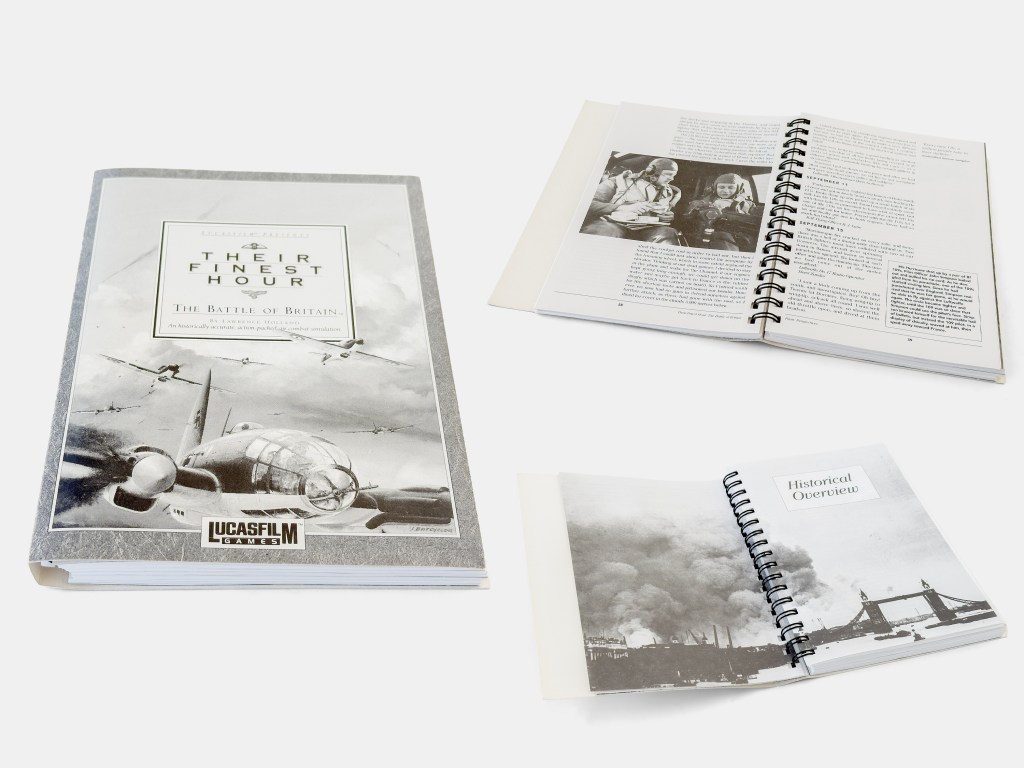

Packaged with the game was a 192-page manual authored by copywriter Victor Cross with contributions by Holland, a comprehensive volume that blurred the line between game supplement and academic resource. It offered players a full historical overview of the Battle of Britain, breakdowns of aircraft performance, and tactical insight into the campaign’s major engagements. Praised not only by players but also by history buffs and critics, the manual was a testament to the game’s ambition, positioning Their Finest Hour as both entertainment and a serious homage to one of World War II’s most defining chapters.

At 192 pages, the manual for Their Finest Hour: The Battle of Britain was a substantial companion to the game, blending detailed instructions with rich historical background. Authored by Lucasfilm Games copywriter Victor Cross, it provided players with aircraft specifications, mission briefings, tactical advice, and wartime context.

The Radio Frequency Cipher Wheel acted as copy protection.

By aligning the smaller wheel with the German unit insignias on the perimeter and typing in the three colored numbers displayed for the correct British airfield, you could tune the frequency of your plane’s radio to receive vital information about enemy aircraft sightings, etc.

Their Finest Hour received widespread critical acclaim upon release. Computer Gaming World hailed it as one of the finest combat flight simulators ever made. Reviewers applauded the game’s blend of authenticity, accessibility, and sheer thrill. Its improved graphics, campaign structure, and attention to detail set a new standard for the genre.

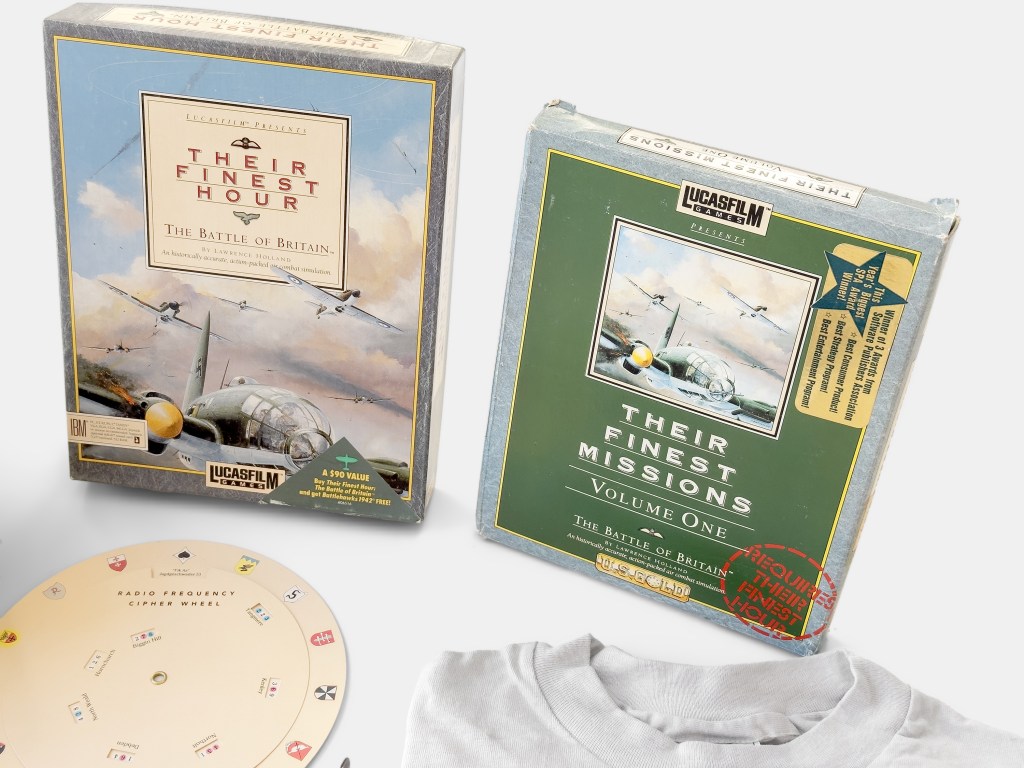

The official Battle of Britain T-shirt was part of Lucasfilm Games’ expanding community outreach in the early 1990s. Available by mail-order and featured in The Adventurer, the company’s in-house magazine filled with developer interviews, behind-the-scenes features, and game news. The shirt was one of several themed items offered to fans. It appeared alongside a brown RAF-style leather vest, a matching leather flight jacket, and even a VHS copy of the 1969 film Battle of Britain, starring Harry Andrews, Michael Caine, and Laurence Olivier.

In early 1990, Lucasfilm Games and Computer Gaming World partnered to host Their Finest Hour: The Battle of Britain Competition, a contest searching for the best virtual pilot. The grand prize? An all-expenses-paid trip to England for the 50th anniversary of the Battle of Britain, accompanied by designer Lawrence Holland and CGW editor-in-chief Russell Sipe. The tour, led by Valor Tours’ Bob Reynolds, included a visit to the Farnborough Air Show, RAF museums, WWII airbases in East Anglia, and even a stop at a famous RAF-frequented pub in Cambridge. The competition itself unfolded across three rounds, with participants submitting pilot records, mission replays, and original scenarios built with the game’s mission editor. The five finalists played each other’s missions, and the top scorer was awarded the once-in-a-lifetime trip.

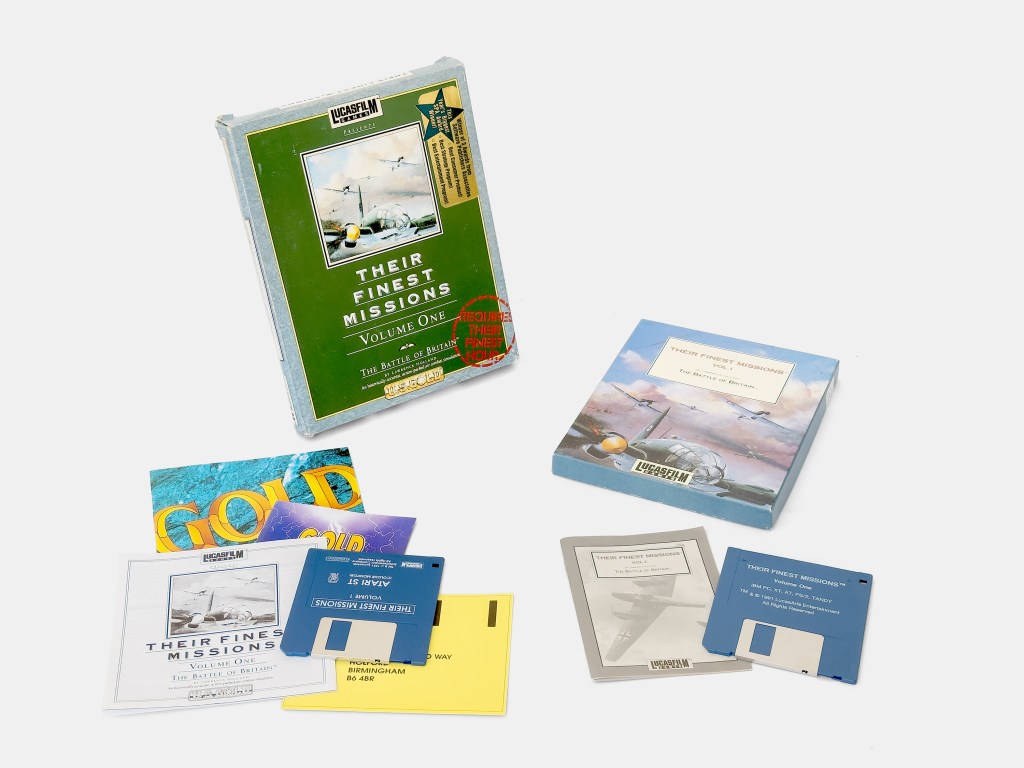

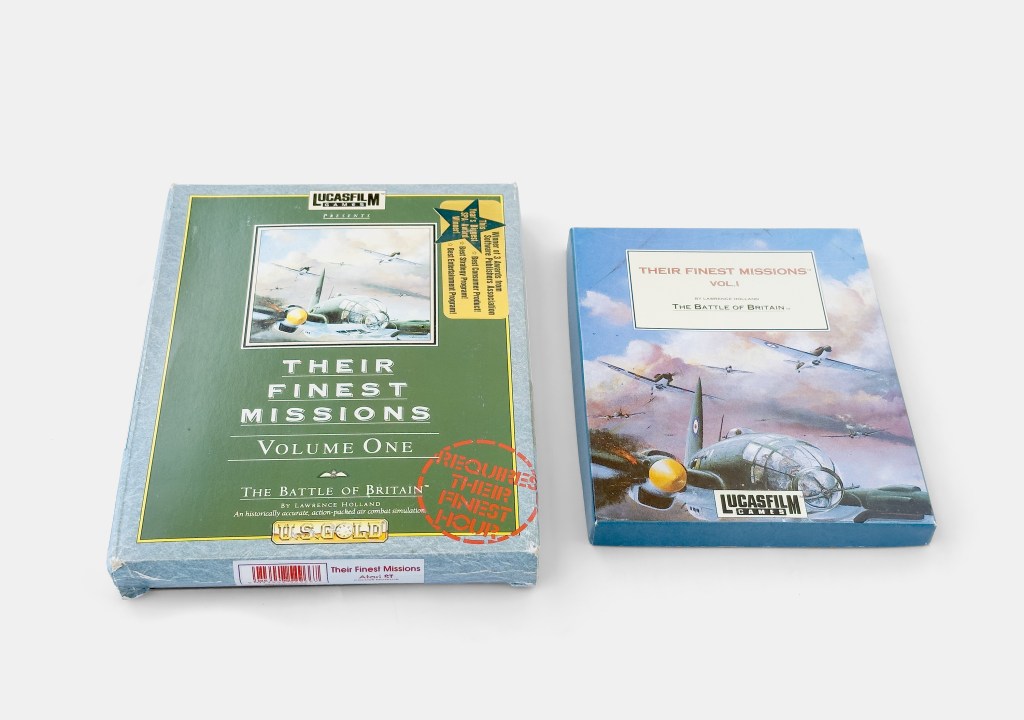

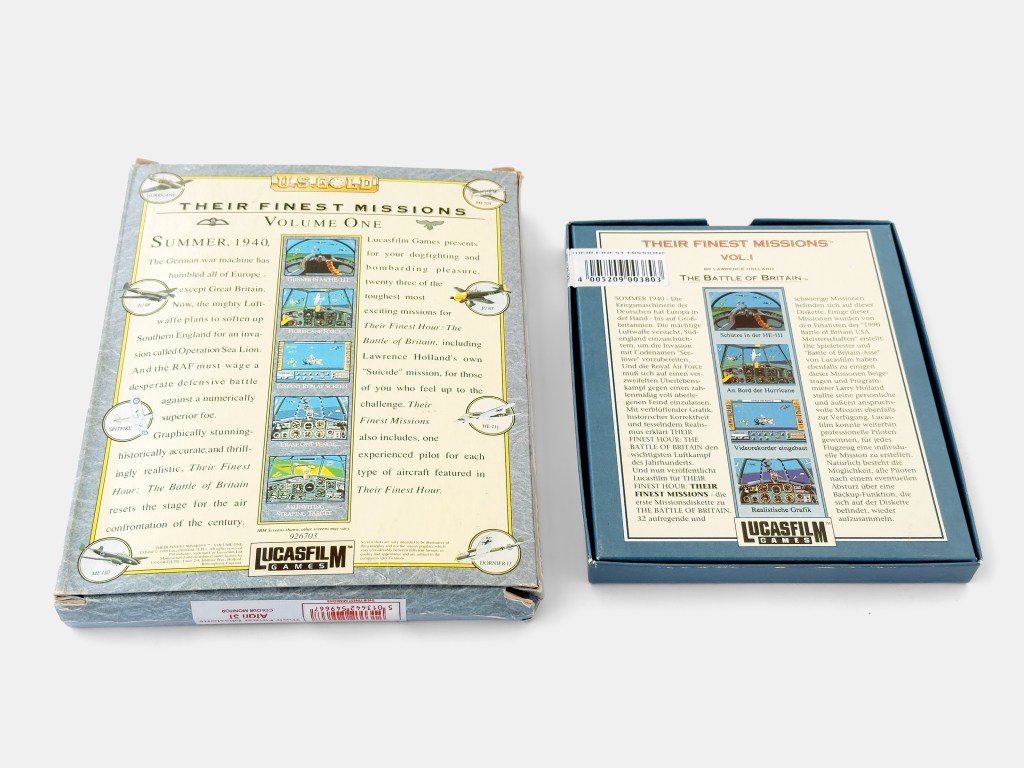

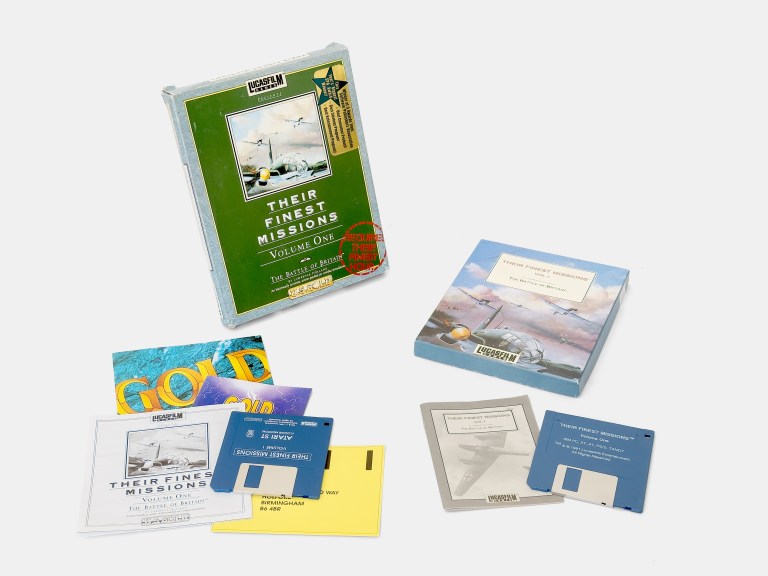

That same year, Lucasfilm released a single expansion pack: Their Finest Missions: Volume One. Its title hinted at future volumes that never materialized, but the disk itself offered plenty. It featured 23 additional missions, some designed by finalists from the CGW competition, as well as one veteran pilot for each of the game’s aircraft. Among the highlights was Holland’s own favorite mission, “Suicide.” In it, players took control of a Bf 110 tasked with bombing and strafing a radar station near Dover while being pursued by six ace Spitfire pilots. The expansion leaned into the series’ strengths with carefully crafted encounters, high-stakes action, and replayability that kept fans engaged long after release.

Their Finest Missions: Volume One was the sole expansion disk released for Their Finest Hour: The Battle of Britain, offering a new set of missions, scenarios, and fighter pilots.

Here, two European retail editions, the UK release by U.S. Gold (left) and the German version (right). In contrast, the original U.S. version was distributed exclusively via mail-order and didn’t come boxed.

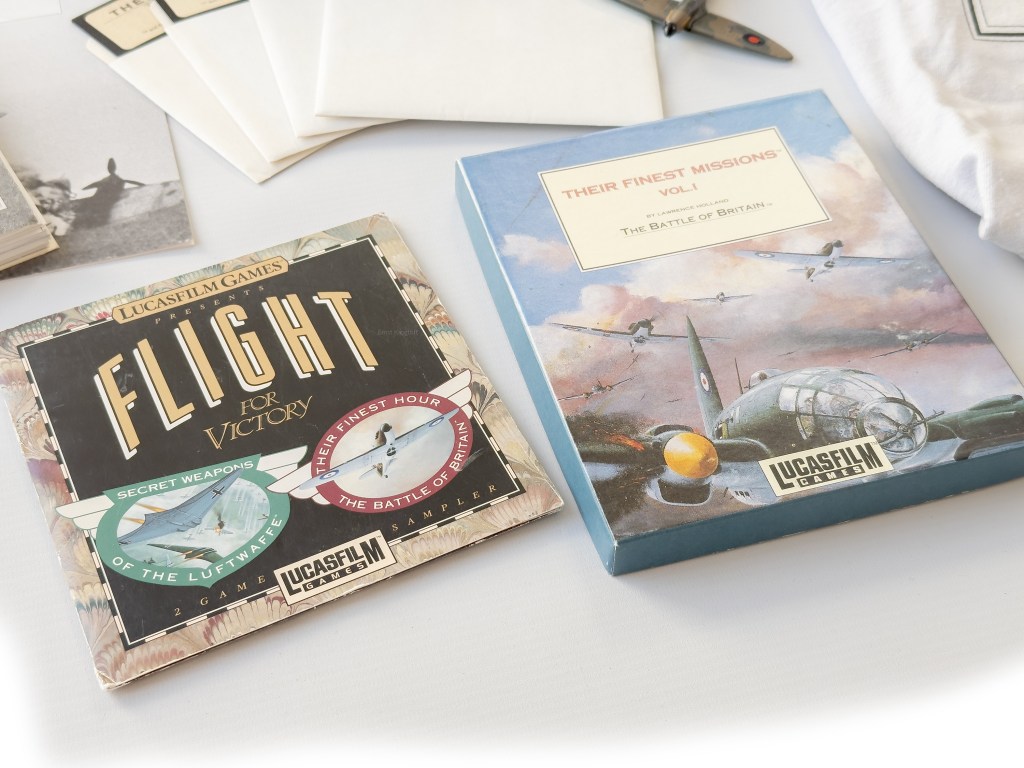

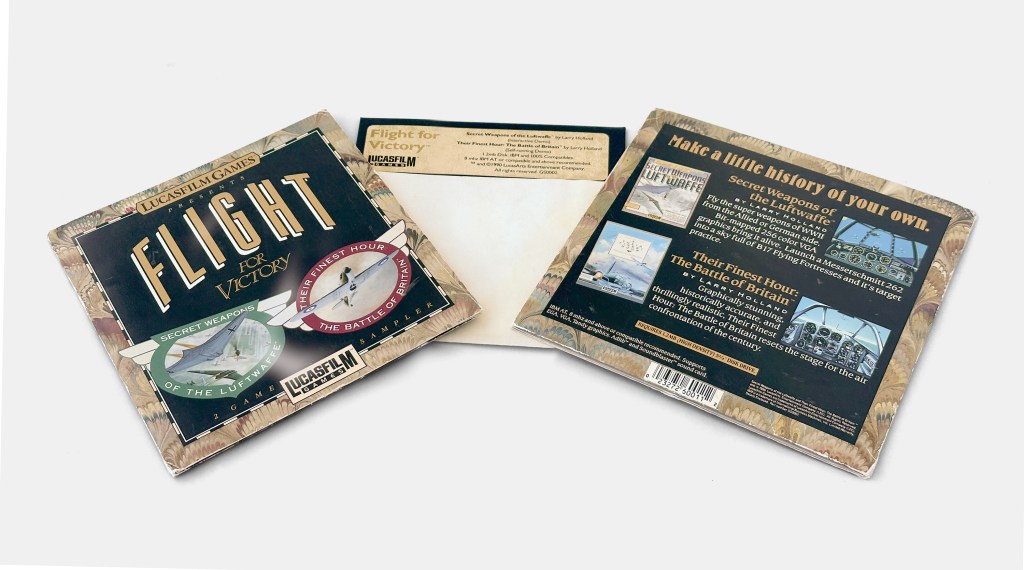

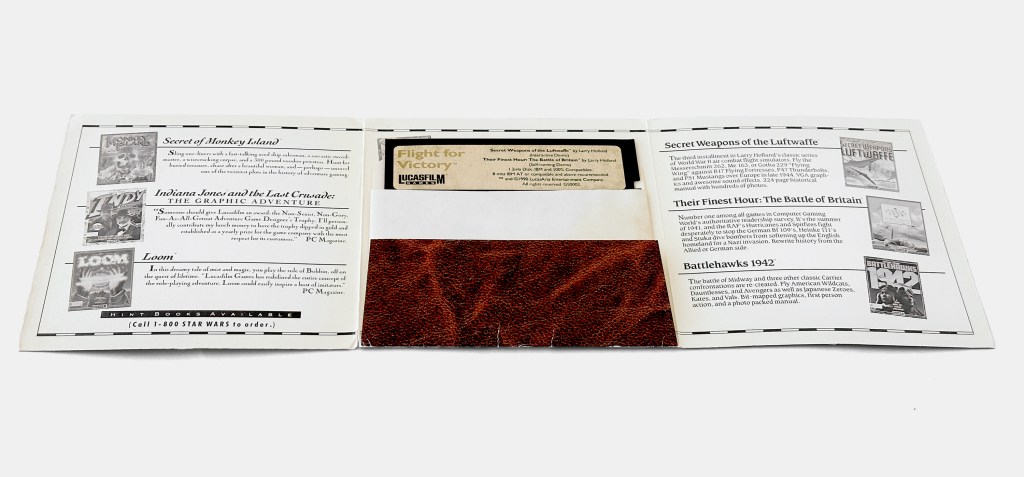

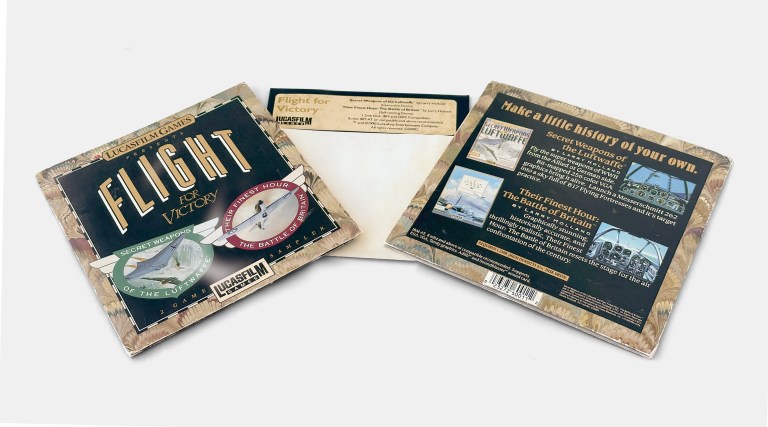

In 1990, a year before the release of Lawrence Holland’s last World War II title, Secret Weapons of the Luftwaffe, Lucasfilm Games created a 5.25″ floppy marketing sampler called Flight for Victory.

The sampler included a self-running demonstration of Their Finest Hour: The Battle of Britain and an interactive sample of the upcoming Secret Weapons of the Luftwaffe.

Their Finest Hour’s success cemented Holland’s reputation and ensured that Lucasfilm Games would continue investing in the flight simulation genre. Two years later, Holland and his team would push the genre even further with Secret Weapons of the Luftwaffe, an ambitious and detailed look at the Luftwaffe’s experimental aircraft and the Allied bombing campaigns over Germany.

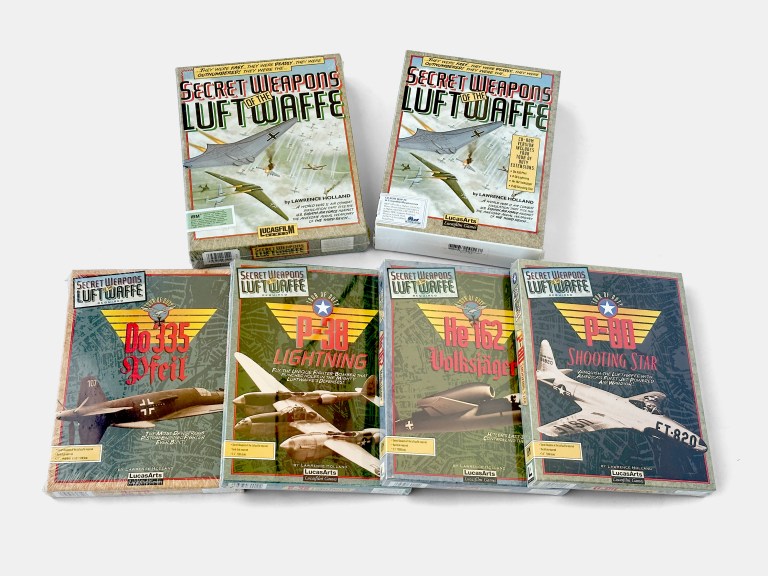

Secret Weapons of the Luftwaffe, Lawrence Holland’s third and final World War II flight simulator for Lucasfilm Games, debuted in 1991.

Here, the original floppy disk edition, all four expansion disks, and the later CD-ROM reissue by The Software Toolworks.

With Their Finest Hour, Holland and Lucasfilm Games delivered one of the most respected and beloved combat flight simulators. After completing his World War II trilogy in 1991, Holland continued his collaboration with LucasArts, co-founding Totally Games and spearheading titles like Star Wars: X-Wing and its sequels, games that brought the same attention to detail and cinematic flair to a galaxy far, far away.

Sources: Computer Gaming World, Wikipedia, Lucasfilm games/Arts’ The Adventurer, DOS Days…

I first became fascinated with air combat simulations on the Amiga: the first ones I played were Jet (SubLogic) and F/A-18 Interceptor (Electronic Arts), but the ones that truly left their mark were Falcon (Spectrum Holobyte) and Their Finest Hour. Despite the hardware limitations, these games managed to recreate the atmosphere and the feeling of actually “flying” and being part of a campaign.

In Their Finest Hour I was astonished during an escort mission when, flying a Bf109, I was trailing a Heinkel 111 bomber at some distance. Suddenly, a Hurricane shot past me, rolled, dropped in behind the bomber—slightly lower than its tail—and raked its least protected section with gunfire. I had just witnessed the very tactic the British used against Nazi bombers.

A few years later, a friend of mine had a 486 PC and, when he showed me Secret Weapons of the Luftwaffe and Wing Commander, I realised the Amiga’s days were numbered.

I was able to purchase a copy of Battlehawks 1942 for the Amiga only a few years ago.

Great post! Thank you.

Thanks a lot, and thanks for sharing a bit of your story – Love it.