A number of years back I did a write-up on Automated Simulations. I finally had some time to take new pictures and also slightly rewrite the article. While I’ve been down-scaling the collecting a bit over the last year, selling off duplicates and “newer” titles, I’m still pursuing missing items, including titles from Automated Simulations, looking for cassettes, disks, etc…

When Jim Connelley founded Automated Simulations in the late autumn of 1978 with the intention of publishing his and Jon Freeman’s first game, Starfleet Orion, the personal computer game market was in its infancy. In fact, it was so new that the company became the first to solely focus on computer games. While companies like Programma International, Apple, and Tandy Radio Shack, among others, were involved in game publishing at the time, it was not their sole focus.

Gary Gygax and Dave Arneson‘s tabletop roleplaying game, Dungeons & Dragons, from 1974, captivated an entire generation and evolved into a cultural phenomenon. Beyond its role-playing aspects and game mechanics influencing a new wave of games and gamers, Dungeons & Dragons also served as a catalyst, inspiring a fresh wave of programmers, aiming to leverage personal computers to streamline the often labor-intensive Dungeon Master bookkeeping, a vital component of conventional tabletop gaming sessions.

In 1977, John Freeman, a seasoned board game player and a regular contributor to GAMES magazine had been introduced to programmer Jim Connelley when he, through a mutual friend, was invited to a game of Dungeons & Dragons hosted by Connelley. With years of experience working as a professional mainframe software developer for a division of Westinghouse, Connelley recognized that most parts of the laborious task of the dungeon master bookkeeping could be automated by software running on home computers.

In the summer of 1978, Connelley purchased his first computer, a Commodore PET 2001. While D&D bookkeeping alone couldn’t justify the $3500, in today’s money, expensive price tag, he sought to mitigate some of his expenses by writing it off as a tax deduction with the intention of developing and selling games. To aid him in the development he contacted Freeman, who with his extensive experience with board games made him an ideal collaborator for crafting foundational rules and establishing mission objectives and background narratives. The two sat out creating their first game, a sci-fi strategy game, with Connelley diligently coding everything in Commodore BASIC.

By November 1978, Freeman and Connelley neared the completion of their two-player game, titled Starfleet Orion. Given the limited number of game publishers available at the time, Connelley made the decision to establish his own company, thus retaining full creative control and avoiding royalty payments. Partly inspired by the name of a rising competitor to Avalon Hill in the realm of tabletop wargames, Simulations Publications, Inc., Connelley picked the name Automated Simulations for his new company. As part of their partnership, Connelley granted shares in the company to Freeman.

When Starfleet Orion debuted on the fledgling market in December of 1978, it became the very first microcomputer sci-fi strategy game. The game revolved around battles between space fleets on a grid measuring 32×64. With The Stellar Union on one side and The Confederation of Orion on the other. The game included 12 increasingly complex scenarios and 22 different ship types. Each player would enter their text commands one after another, and at the end of a round, the turns were executed simultaneously. A scenario would end when all ships on one side were destroyed or had escaped the playfield.

Connelley and Freeman had no background in computer game publishing, but in 1978 only a few people did. The duo hired a local printer and typesetter to print a number of manuals, bought a bunch of plastic bags, and duplicated the cassettes by hand. For the first six months, the whole production and distribution process was run out of the spare bedroom in Connelley’s apartment.

While Starfleet Orion was originally programmed in BASIC for the Commodore PET, the duo decided to release a TRS-80 version of the game first. The TRS-80 computer not only appealed more to gamers by being more home-oriented but also boasted a significantly larger user base than the PET. As all different BASIC versions irrelevant to computer architecture were quite similar, the game could somewhat easily be converted and adapted.

The Commodore PET and TRS-80 versions of the game were similar and both were released on cassette tapes. Players had to manually input the scenario data from the included Battle Manual and save it to a separate cassette before playing, a very slow and tedious process. The release of the Apple II version in 1979 marked a significant improvement as it came on floppy, which provided enough storage space to encompass all the scenarios and thereby didn’t require the user to type in long strings of text. Additionally, players were given the ability to create their own scenarios using a separate builder program and save them to either cassettes or floppy disks.

The Apple II version stood out from the PET and TRS-80 versions, featuring a basic graphic representation of the ships instead of mere dots. Nonetheless, the overall gameplay remained text-based, employing symbols like asterisks to depict explosions, much like in the PET and TRS-80 versions.

Automated Simulations’ first title, Starfleet Orion, was initially released for the TRS-80 in late 1978.

A Commodore PET version followed shortly after and in 1979, the game became available for the Apple II.

In 1979, Automated Simulations released Invasion Orion, a follow-up to Starfleet Orion but designed as a single-player game. One of the weak points of Starfleet Orion was it required two players to play. Invasion Orion allowed players to enjoy the same game mechanics while engaging in battles against the computer. It also offered larger scenarios, introduced eight additional ship types, and included an editor that allowed players to create their own scenarios and design new ships.

Invasion Orion was written for both the Commodore PET and TRS-80 and published simultaneously with an Apple II version following shortly thereafter.

In 1981, the title was re-released for the Atari 8-bit platform under the Epyx brand name. Interestingly, this version reintroduced a two-player mode, providing an option for multiplayer gameplay in addition to the single-player experience.

Invasion Orion was released for the Commodore PET, TRS-80, and Apple II in 1979.

The PET and TRS-80 versions were published at the same time with the Apple II version following shortly thereafter.

A boxed version, which included a version for the Atari 400/800, followed in 1981.

Starfleet Orion and Invasion Orion stand as the sole entries in the saga of the Stellar Union and the Orion Confederation. A third title dubbed Star Trader Orion was briefly mentioned in an Automated Simulations promotional catalog in late 1979. The catalog announced an expected release date in August 1980. Unfortunately, it never came to fruition, and the catalog remains the only known mention of the title.

While working on Invasion Orion, Connelley, and Freeman attended a Dungeons & Dragons convention, with the aim of promoting their sci-fi computer simulations to the traditional roleplaying board gamer. They soon discovered that the majority of attendees showed little to no interest in sci-fi simulations. If they were to pull in traditional board gamers to their games they needed to shift focus. The realization that action and roleplaying games held the potential for a significantly larger audience, also resonated more closely with their shared passion for pen-and-paper Dungeons & Dragons. In response, Connelley and Freeman created a subbrand that could encompass forthcoming titles extending beyond the simulation genre.

Following the release of Invasion Orion, Freeman, and Connelley began designing a fantasy roleplaying game inspired by Dungeons & Dragons. The two were joined by Jeff Johnson, who had been participating in their Dungeons & Dragons sessions, to assist with level design and enemy character creation.

Freeman took charge of devising a role-playing rule system that would seamlessly integrate with Connelley’s newly developed BASIC engine. The system drew significant inspiration from the mechanics of Dungeons & Dragons and even allowed for the importing of pen-and-paper characters.

The first game to utilize the new engine and ruleset was Temple of Apshai, initially developed for the TRS-80 and released in 1979. The PET version was released shortly thereafter, followed by an Apple II version developed by a third party in 1980.

Temple of Apshai, the company’s third title, marked a departure from the sci-fi genre and played a pivotal role in shaping the company and its success in the years that followed

Temple of Apshai, like the earlier sci-fi titles from Automated Simulations, was initially developed in BASIC and lacked sound and sophisticated graphics. Players would create their characters using standard Dungeons & Dragons attributes, descend into the dungeons, uncover treasures, find weapons, discover hidden doors, engage in battles with enemies, and gain experience. The gameplay was turn-based, with the player and enemies taking turns to perform actions. The game encompassed four dungeons set in the ruins of the ancient temple of the god Apshai, with each dungeon progressively increasing in difficulty. The combined dungeons offered over 200 rooms to explore and featured a variety of 30 different monstrous creatures.

While the graphics in the initial releases were rudimentary, consisting of basic blocks and lines, the game included a comprehensive 56-page manual known as the Book of Lore. This vividly described every room in the game, providing crucial information and contributing to the immersive setting of the game.

On cassette releases, one side had the Innkeeper program where you would generate characters and define their strengths and weaknesses, and make purchases of weapons and armor. The other side had the Dungeon-master program, providing the gameplay experience within the dungeon. Notably, the cassette versions didn’t have a built-in save feature, requiring players to manually write down all their character statistics before quitting the game. Reloading a saved game necessitated reentering the information manually. Later versions, released on floppy, however, addressed this limitation by enabling players to save all their character statistics directly to the disk, offering a more convenient and streamlined experience.

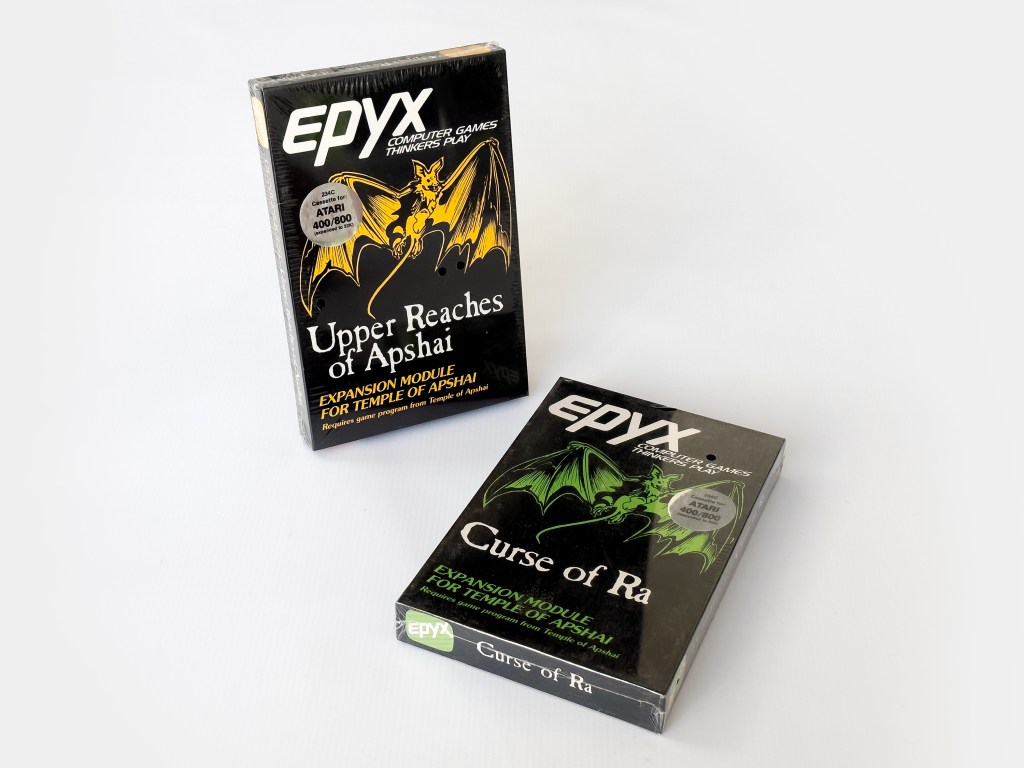

Temple of Apshai was extensively advertised in traditional roleplaying game magazines, targeting conventional players who might be interested in pursuing computerized roleplaying games. However, it soon became apparent that potential buyers of computerized roleplaying games came from all walks of life and not just from. were not limited to a specific audience, and the game quickly grew into one of the biggest commercial success stories of the time. It spawned two expansions branded under the Dunjonquest label, Upper Reaches of Apshai and Curse of Ra.

The two expansions for Temple of Apshai, both boosted four new dungeons each and required the original game since the expansions were nothing more than data files that had to be loaded through the original game. Upper Reaches of Apshai, from 1981, played out in the innkeeper’s backward and had a more humorous tone.

Curse of Ra, the third and quite more difficult expansion was set in ancient Egypt and released in 1982.

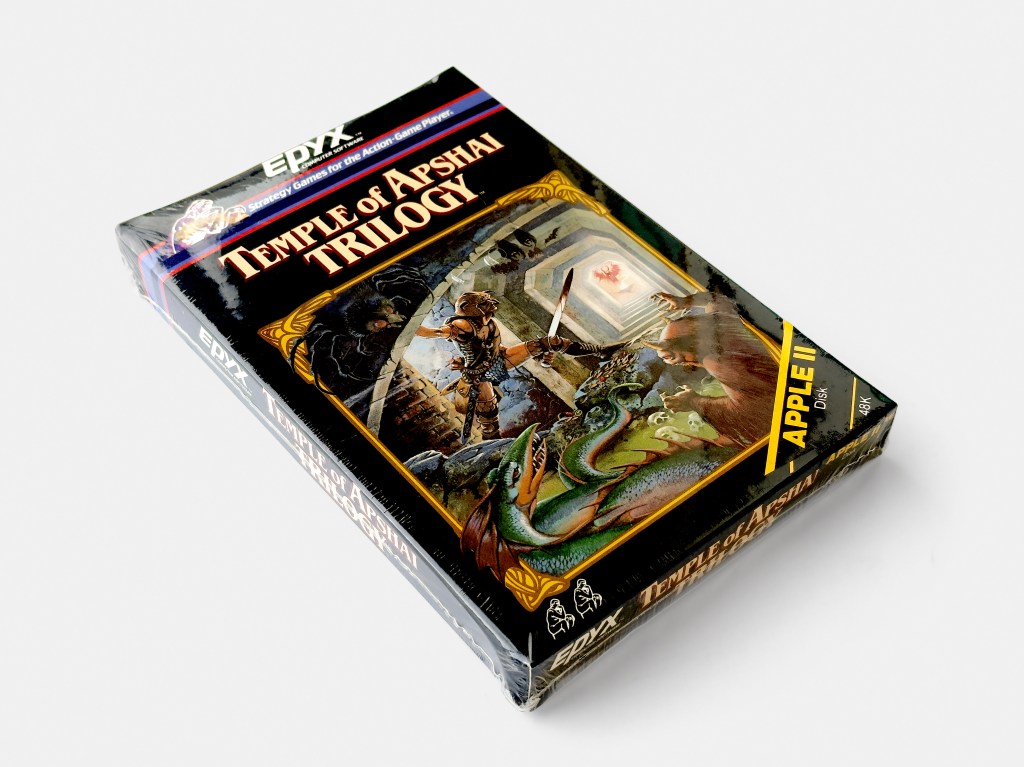

Temple of Apshai, Upper Reaches of Apshai, and Curse of Ra ended up being so successful, or at least Temple of Apshai did, that they were re-released in 1985 as the Temple of Apshai Trilogy with updated graphics, sound, and music.

Westwood Studios was responsible for porting the trilogy to the 16-bit computers of the time.

Temple of Apshai was rated as the best computer game by nearly every magazine of the era and went on to become a huge commercial success with well over 30,000 copies sold by mid-1982.

With the two Sci-fi strategy games well behind them, Automated Simulations no longer resonated well with the themes of the upcoming games. To address this, Freeman and Connelley came up with the name Epyx as an alternative to Epic, which was already being used by a record company. Epyx served as a distinct brand under which future action and roleplaying games would be released,

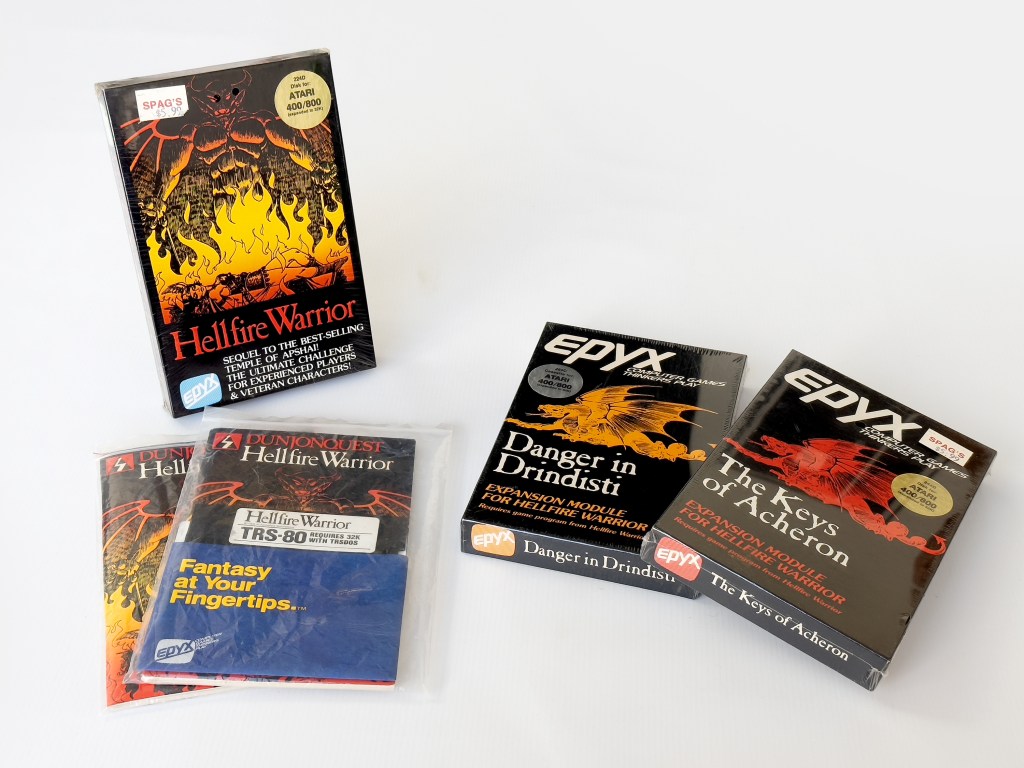

In the coming years, similar titles in the Dunjonquest line were published. These included the direct sequel Hellfire Warrior and its two expansion packs, The Keys of Acheron and Danger in Drindisti, all of which featured four dungeons.

Hellfire Warrior, the only direct sequel to Temple of Apshai, was released in 1980 with a re-release the following year.

Hellfire Warrior spawned two expansion packs, The Keys of Acheron from 1981 and Danger in Drinsti from 1982

After the initial success with Temple of Apshai in 1979, Automated Simulations wanted to address beginners and less experienced players who wanted a taste of roleplaying and dungeon crawling and created the MicroQuest series. The series would limit titles to only one dungeon and no character generator. The first game in the series, The Datestone of Ryn, released in 1979 also had a 20-minute time limit for you to complete the game.

The second title, Morloc’s Tower, initially referred to as Dunjonquest #3 was placed in the MicroQuest series as it was simpler than Temple of Apshai and featured more notable adventure game elements than the other Dunjonquest titles.

The Datestone of Ryn and Morloc’s Tower ended up being the only titles in the MicroQuest series. Due to the smaller size, these were sold at half the price of their larger siblings.

Created upon the success of Temple of Apshai, Morloc’s Tower and Datestones of Ryn from 1979 became the sole entries in the MicroQuest series. Both titles were later rereleased in the standard-sized Epyx box.

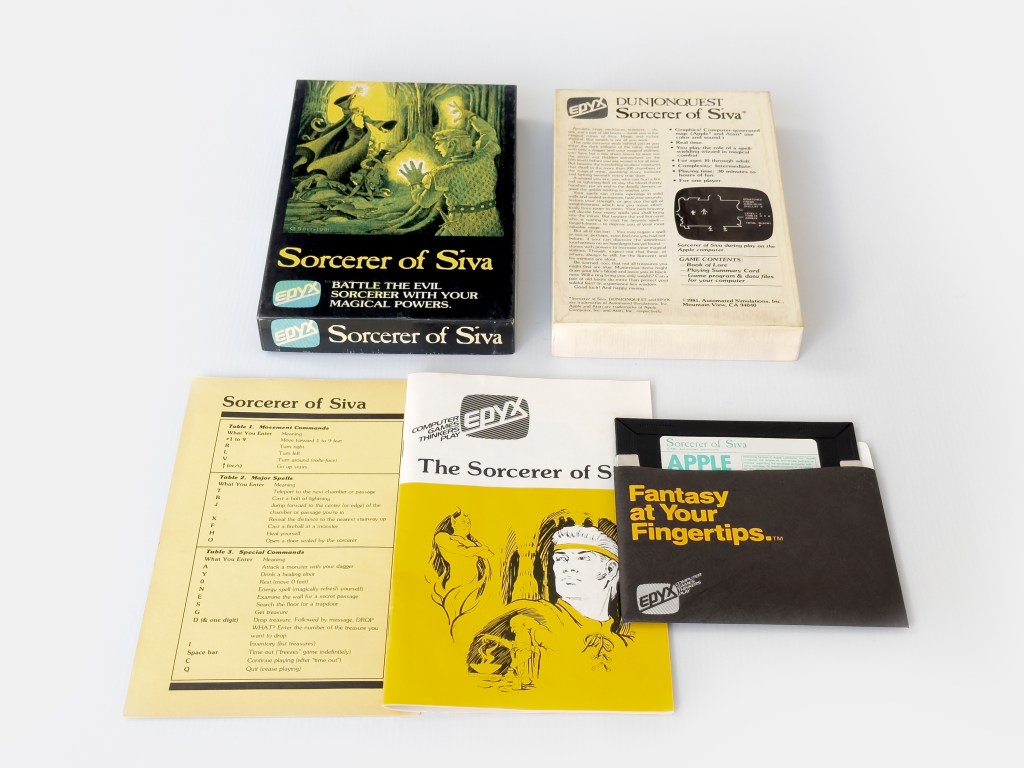

A third title in the MicroQuest series, Sorcerer of Siva was being developed but as it fell between the MicroQuest and the full-fledged Dunjonquest games in size it ended up as the last standalone title under the DunjonQuest label. Following its release in 1981, the MicroQuest label was abandoned.

Sorcerer of Siva, released in 1981, was the last standalone title in the Dunjonquest series.

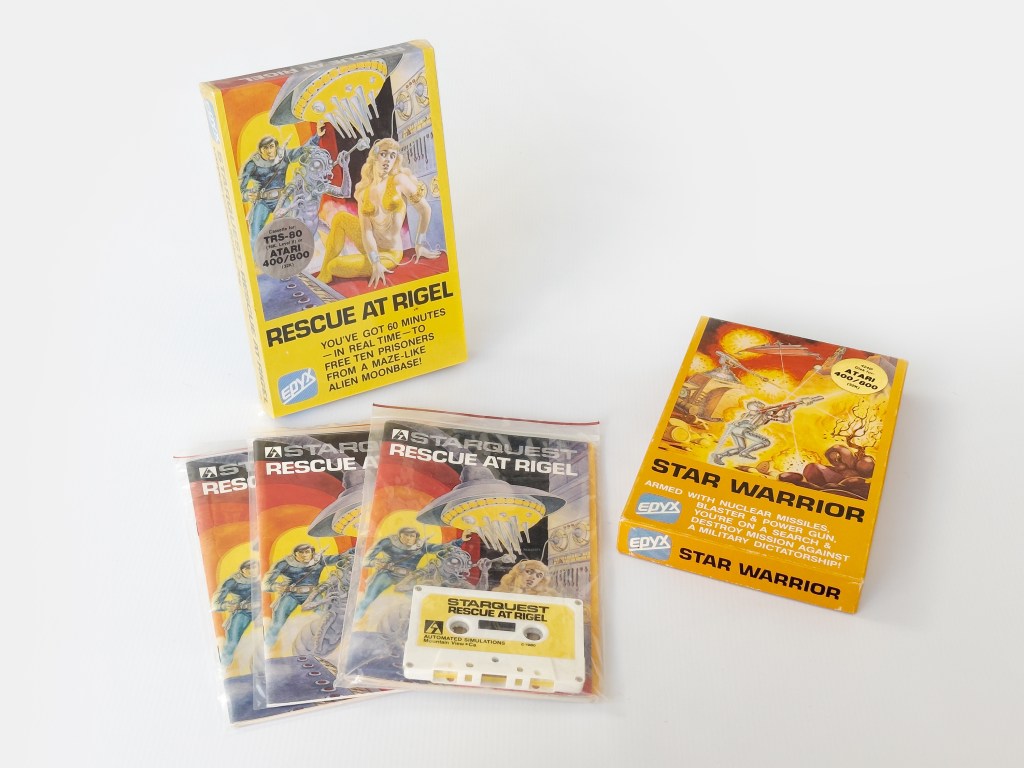

Connelley’s BASIC engine was modified and used in the Starquest sci-fi series, which like the MicroQuest only ended up consisting of two games. The initial installment, Rescue at Rigel, from 1980, deviated from the dungeon setting and instead played out on a space station. The game featured a storyline paying homage to several iconic science fiction heroes, such as Buck Rogers, Lazarus Long, and the characters from Star Trek and Star Wars.

The second and last title in the series, Star Warrior, leaned more towards strategy and marked the first among the Dunjonquest and related titles to unfold in an outdoor setting.

The Starquest series came to include two titles, Rescue at Rigel released in 1980, and Star Warrior, released the following year alongside a boxed rerelease of Rescue at Rigel

The lineup of Automated Simulations’ titles, releases from 1978-1980, including the Special Offer 3 Pak.

Most of the titles were later released in boxed format for an array of personal computers.

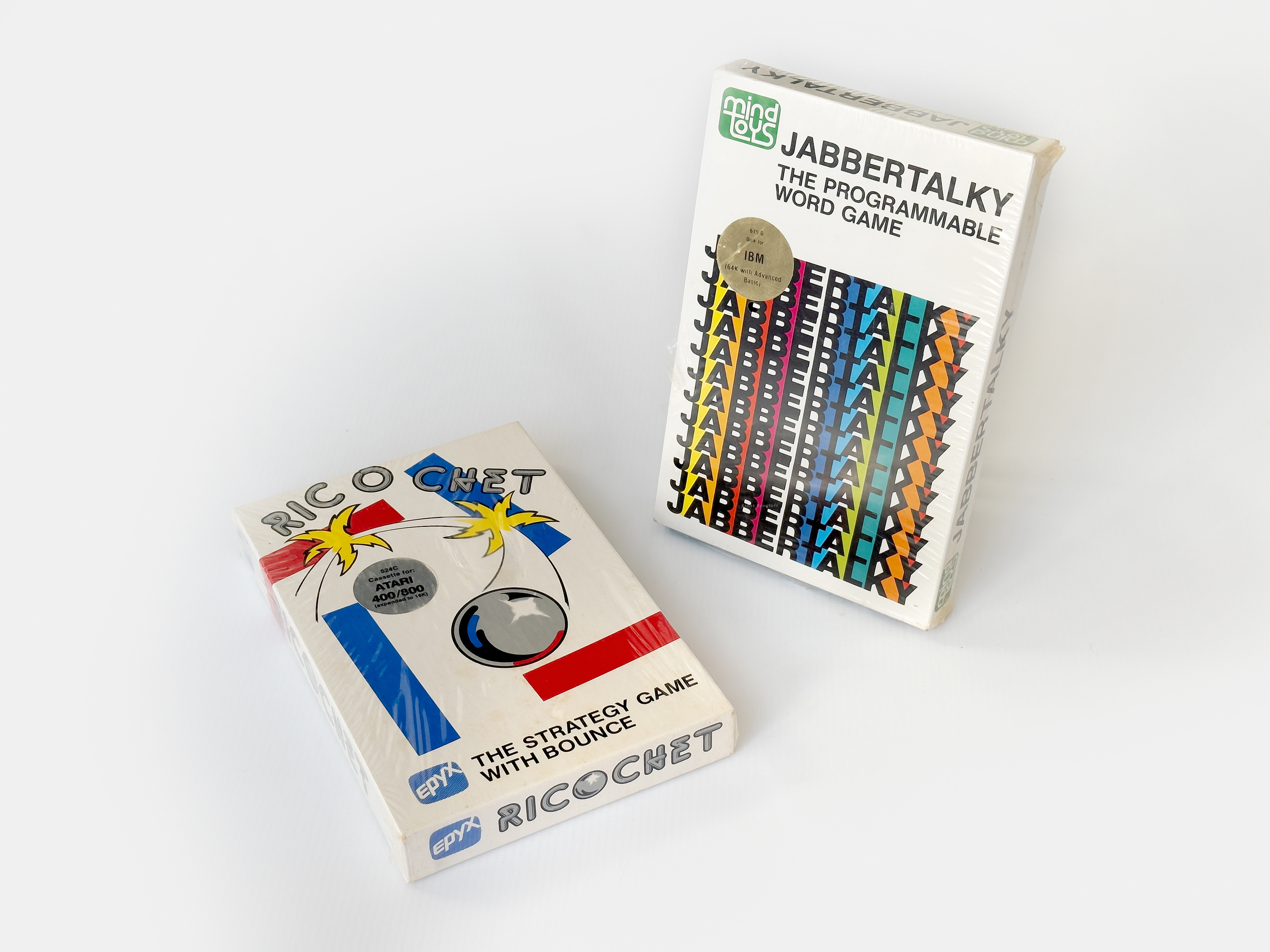

In 1981 Automated Simulations would release two titles in its newly created Mind Toys series. These would take a step away from fantasy and focus on the mind. The two small but innovative titles in the series were Jabbertalky, a word game, and Ricochet, a trajectory-based cannonball game. None of the titles gained notable success and the brand was dissolved in 1983.

Jabbertalky and Ricochet from 1981, the only two titles released in the shortlived Mind Toys series.

While the Dunjonquest games, particularly Temple of Apshai, enjoyed significant success and recognition, they also gave rise to fierce competition. Richard Garriott‘s Ultima and Sir-Tech‘s Wizardry role-playing games surpassed, in nearly every aspect, what Connelley’s aging 1979 BASIC game engine could deliver. Despite its portability and compatibility with various computer systems, the engine’s performance was sluggish and increasingly limited on newer platforms like the Atari 8-bit line of computers.

In late 1981, Freeman, dissatisfied with Connelley’s reluctance to abandon his engine and develop a new, modern, and more powerful one that could compete with the likes of Ultima and Wizardry, made the decision with soon-to-be-wife Anne Westfall to part ways with Automated Simulations. The two, together with Paul Reiche III went on to found Free Fall Associates, with a focus on writing games for the Atari 8-bit computers. Freeman and Westfall would go on to create the two award-winning and highly acclaimed games Archon and Archon II for Electronic Arts. Paul Reiche would, later on, co-create Star Control and Star Control II with Fred Ford, arguably some of the best space-themed games of the 20th century.

With Freeman gone and sales plummeting, investors were getting concerned and brought in new key personnel to rework the company. Connelley was slowly but surely eased out of his own company and in 1983 he left with a number of employees to found The Connelley Group which would release a handful of games including his last title to be published by his old company, Dragonriders of Pern.

While Epyx was originally only meant as a brand name, the name was shorter, more appealing, and less geeky-sounding than Automated Simulations. With the new management reworking the company, Epyx evolved into the company name. From 1980 to 1983 both names would appear on game boxes and content but following the reconstruction, Freeman and Connelley’s Automated Simulations name was canned for good.

With a new name and management, the company went more mainstream publishing Randy Glover‘s hugely successful arcade game Jumpman. Topping sales charts for months on end, it became one of the bestselling Commodore 64 games of 1983, enough to put Epyx back in the green.

Over the next many years, Epyx saw much success with its action and sports games.

I have Starfleet Orion & The Datestones of Ryn for the PET, released in EU by Commodore. They use the same cassette inlays as they did for most of their PET games/titles, with the title stamped to the front inlay and cassettes.

Tried to bid on the US PET tape versions of Hellfire Warrior & Rescue at Rigel in 2021 when both appeared on ebay, but as the price ended at over $100,- per tape, I tapped out. I see where they ended up now ;)

Amazing photos I must say. You never get the problem I have with light reflecting the inlays or tapes? Guess you got a better camera and maybe use a tripod with long exposure time? Steady she goes… :D

Thanks:) I actually do have issues with reflections as I have big windows but I always try to shoot when overcast. All photos are actually taken with various generation of iPhones with items placed on a white photo backdrop (no artificial lights, tripods, or anything else) – I adjust white tones, curves, etc.