Out of the three publishers, Christopher Crim sent out his newly completed fantasy roleplaying game to, Sierra On-Line was the first to respond positively and extended him an invitation to their Oakhurst headquarters for a tour and discussion regarding a potential publication of the game.

Sierra On-Line had four years earlier, in 1982, published Richard Garriott‘s second Ultima title, Revenge of the Enchantress, and while the title had gained significant success and recognition, Garriott and CEO and co-founder of Sierra, Ken Williams didn’t see eye to eye. Garriott had the desire to have full autonomy within his projects, something Williams wasn’t accustomed to. Williams had agreed to publish Ultima II on Garriott’s terms which included full creative freedom without the involvement of Sierra, a high royalty rate, and a full-color cloth map to be included in the box, greatly impacting the production cost, at Williams’ expense.

Garriott had a strong vision for his Ultima games but felt constrained by the corporate structure and decision-making processes at Sierra. Williams had a more conservative approach to game development and preferred to stick to proven formulas and established mechanics. Disagreements regarding royalties of the IBM PC version of Ultima II, along with other disputes, and Garriott’s desire to self-publish his games, led to the parties separating somewhere in late 1982, leaving a notable hole in the Sierra catalog.

Garriott was not only a divinely gifted programmer and game designer but an intelligent and competent businessman as well, after all, he had managed to out-negotiate Williams on the Ultima II deal. Following his departure from Sierra, Garriott went on to co-found Origin Systems and would continue to build up the Ultima brand into one of the strongest franchises in the business.

While Sierra experienced challenging times during the tumultuous period of the North American video game crash in 1983-84, the company ultimately made a significant impact by popularizing the graphic adventure game genre through its highly successful King’s Quest series of games. Sierra, aware of the achievements and acclaim garnered by Garriott’s Ultima titles, recognized the potential when Crim’s Ultima-inspired fantasy roleplaying game, Wrath of Denethenor reached its doorsteps. This was an explicit opportunity for the company to yet again capitalize on the popularity of the roleplaying genre and fill the void Garriott had left.

Crim had dedicated most of 1984 and 85 to developing Wrath of Denethenor, coinciding with his final year of high school and first year of college. The inspiration had come from Garriott’s Ultima II and later Ultima III but he opted to depart from the conventional but complicated approach of stat-centric role-playing games with predetermined character roles and aimed it at novice players with gameplay emphasis on exploration allowing players to assume the role of a generic character and play in a manner aligned with their personal preferences throughout the extensive game world.

Crim had earlier written a few programs for his high school friends to try out and even successfully sold a customer database system to a local newspaper for $100 but nothing as complex as the current task at hand. He aimed to surpass the games that inspired him in both complexity and scale. The sheer size of the undertaking was impressive and quite comparable to the extensive effort Garriott, solely had invested in Ultima II.

While earlier efforts mainly had been programmed in BASIC on his 64K Apple II computer a game of Wrath of Denethenor’s size and sophistication had to be done in Assembly language. High school friend Kevin Christiansen wrote the graphics routines and tools and helped with the visuals.

After completing Wrath of Denethenor, in 1985, Crim handed it to friends to playtest, before a copy was sent to three potential publishers, one of which being Sierra On-Line.

Although Sierra On-Line regularly received game project submissions from individuals hoping to make it in the industry, it was a rare occurrence to receive a fully developed, thoroughly tested, and bug-free game of such magnitude, accompanied by a well-written overview of everything. The project possessed all the necessary elements to fill the void left by Garriott and might even have the potential to achieve similar commercial success. The parties agreed on a deal with a few specific requests from each side.

As the Apple II, as a viable gaming platform, was giving way to more potent systems, Sierra requested the game to be ported to the Commodore 64. Due to the two systems sharing the same 6502 processor Crim was able, with only minor tweaks, to rewrite the complete game but it necessitated him, singlehandedly, to rewrite all of the graphics routines. To mitigate the risk of potential intellectual property infringement, common names such as orcs, dragons, skeletons, etc had to be renamed.

Both Crim and Christiansen felt that many games were prone to piracy due to their high cost and made a bold proposal to Sierra, suggesting that the game be marketed at half the usual price and completely eliminate copy protection. Crim believed that by offering the game at a significantly reduced price, Sierra could potentially sell three times as many copies while simultaneously discouraging piracy. Surprisingly, Sierra agreed to the unconventional idea and even issued a press release to announce it as an experiment aimed at boosting sales through lower pricing and the omission of copy protection measures.

With the changes completed and the Commodore 64 version ready, Sierra put Wrath of Denethenor through its quality assurance process where it passed with flying colors and was published in 1986.

While being developed for the Apple II, author Christopher Crim ported it to the Commodore 64 by request of Sierra On-Line. Both versions were released in 1986.

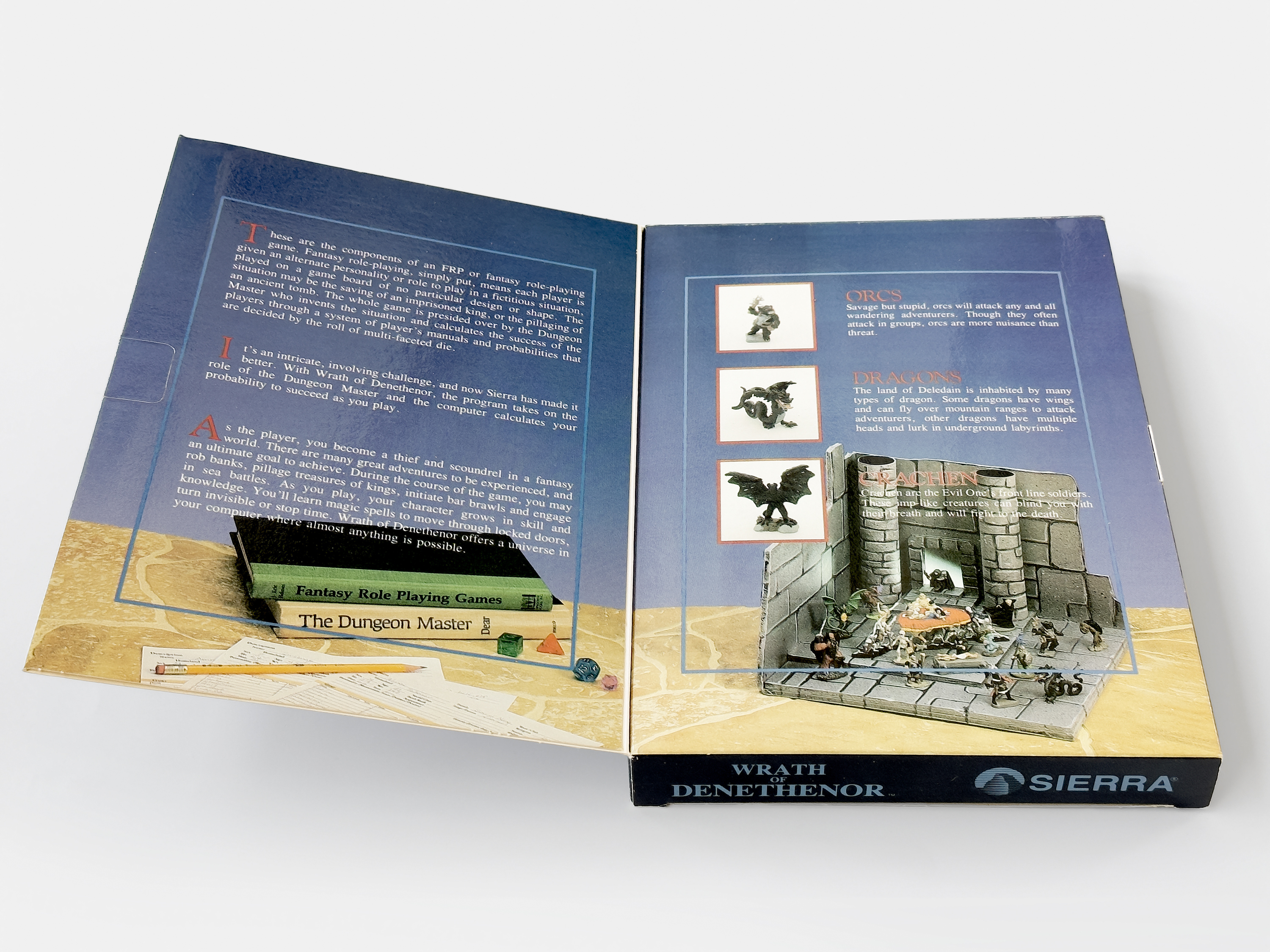

The box design was done without Crim’s involvement and to his dismay, depicted elements with no real connection to his game.

The content included a note from Crim, conveying his view on piracy and the pricing strategy used

Ironically, the gatefold depicted creatures with classic fantasy names as orcs and dragons, the same names Sierra had requested for Crim to rename in the game to avoid any potential infringement

Wrath of Denethenor was impressive in its sheer size and was exceptionally well-executed. The inspiration from Ultima was evident but without heavy stat-centric elements, it was more accessible to newcomers to the genre. The game took up both sides of two 5.25″ floppy disks and boasted five major game areas, each with its own towns, castles, mazes, etc…

Contemporary reviews praised Wrath of Denethenor as a well-crafted game but criticized it for its lack of originality. During the time of its release, sales of Origin System’s newest installment in its Ultima series had already surpassed 100,000 copies and had taken the top spot on Billboard‘s list of software best sellers for February and March 1986. Before the end of the year, Ultima IV: Quest of the Avatar was named Game of the Year.

While being the game to fill the roleplaying gap in Sierra’s catalog, Wrath of Denethenor, strangely, never received any major marketing efforts and with Ultima’s dominance in the roleplaying market, Wrath of Denethenor failed to achieve any notable commercial success. It’s estimated that only a few thousand copies sold before it was pulled from the market a year or two later.

Seven years after the success of Garriott’s Ultima II, Sierra would finally have another successful title in the genre with the introduction of Corey and Lori Ann Cole‘s excellent Quest for Glory series of games with the first installment, Hero’s Quest, being released in 1989.

In 1988, Crim joined Claris Corporation, later FileMaker, Inc. as a software engineer, where he stayed for more than 30 years. In the early ’90s, he started a hobby adventure game project with a friend and coworker but work got in the way.

Crim is now retired and an avid world traveler and blogger.

In Ken Williams’ autobiographical book, Not All Fairy Tales Have Happy Endings, he briefly mentions Ultima and Richard Garriott, highlighting Garriott as one of the fish that got away.

Sources: crimdom.net, Wikipedia, InterAction, LinkedIn, The Sierra Adventure by Shawn Mills, Not All Fairy Tales Have Happy Endings by Ken Williams…