In the late 1970s, Dave Mannering was starting to feel the weight of his profession. Still early in his career as an air traffic controller, he had already learned that the job wasn’t for the faint of heart. Every decision mattered, and every instruction carried consequences. From his position at Tulsa International Airport in Oklahoma, Mannering was responsible not just for schedules and spacing, but for lives moving through the sky at hundreds of miles an hour.

After only a few years on the job, the pressure had gotten to him. Mannering decided to step away from professional air traffic control and pursue other interests, but the experience itself would not quite let go of him. On his TRS-80 microcomputer, he began recreating the systems, procedures, and pressures of the control tower, not as training software, but as a way to explore the job’s logic without the real-world stakes.

What emerged was a small piece of software that authentically translated the invisible choreography of airspace management into a playable experience. Players were dropped directly into a simplified but recognizably authentic control environment, where judgment, timing, and overview mattered as much as quick reactions.

At the time, creations like Mannering’s rarely followed any formal path to publication. The infrastructure simply wasn’t there yet. Instead, programs circulated through user groups, newsletters, magazine listings, and personal correspondence, passed hand to hand among a small but intensely curious community of early microcomputer enthusiasts. Developers mailed cassette tapes across state lines, swapped source code at local meetings, or sent their work directly to magazines such as Creative Computing, whose editors often acted as gatekeepers, curators, and sometimes even collaborators.

Founded in 1974 by David H. Ahl, Creative Computing began life as a magazine devoted to the emerging world of home computers at a time when the concept of a “home computer market” barely existed. The magazine quickly distinguished itself by treating computing not as an academic pursuit or a corporate tool, but as a creative, exploratory activity. Its readership included hobbyists, engineers, educators, and professionals, people who were programming machines in their homes, offices, and classrooms, often inventing entirely new uses for them along the way.

Over time, Creative Computing grew into a multifaceted operation. The magazine served as a forum for ideas, type-in programs, commentary, and reviews. Alongside it, the company established a book publishing arm, releasing influential titles such as BASIC Computer Games, which helped define how early users learned to program and think about software. Through its book service, Creative Computing also became a mail-order distributor, selling not only its own publications but a wide range of third-party computer books to a geographically dispersed audience hungry for information.

Out of the ecosystem grew a software publishing arm, one that was less concerned with mass entertainment and more aligned with the magazine’s spirit of intelligent, challenging, and often educational programs for home and small-business computers. Creative Computing’s software catalog reflected the interests of its readership, including simulations, strategy games, business tools, and utilities that explored what microcomputers could do.

Creative Computing did not rely on an industrial pipeline of professional developers. Instead, it drew from the same pool as its readers. Programmers often came to the company through personal contacts, magazine submissions, or demonstrations of software that showed originality and depth. Many were professionals in other fields, teachers, engineers, scientists, who used computers as an extension of their work rather than as an end in themselves.

In that sense, Mannering’s path to publication was entirely typical of the era. His Air Traffic Controller program was not conceived to chase trends or compete with arcade hits (the few that existed at the time). It was a thoughtful simulation born of real experience, written by someone who understood the system he was modeling and believed that a home computer could meaningfully represent it. Creative Computing recognized that value, and for Mannering, this meant his creation could reach beyond his own computer and into the hands of eager players.

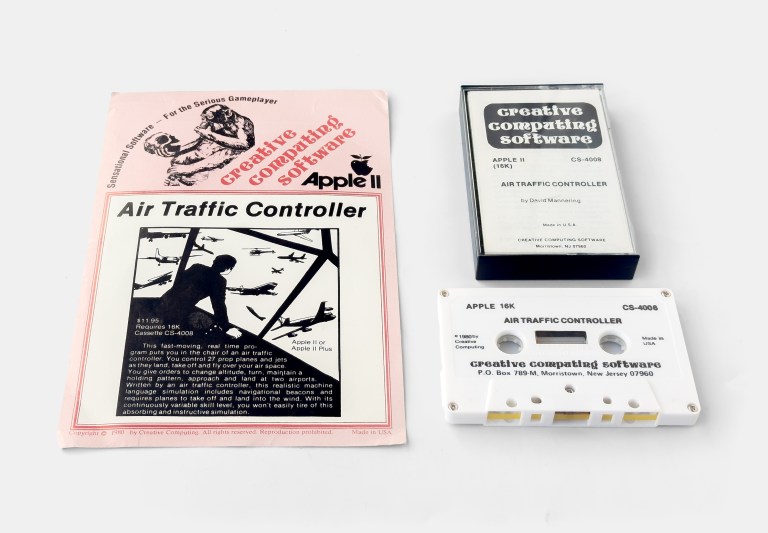

In 1978, Creative Computing released Mannering’s Air Traffic Controller for the TRS-80 Model I. The TRS-80 was, at the time, the best-selling off-the-shelf home computer, quickly gaining traction among creative programmers and hobbyists. The game fitted neatly into Creative Computing’s catalog of thoughtful, intellectually demanding software, a niche where it found success. The success led to ports to additional platforms, most notably the Apple II in 1980, as well as versions for the Sol-20 and Exidy Sorcerer. Each port preserved the game’s essential mechanics, adapting to different hardware while retaining its text-based input and interface.

Creative Computing began listing the Apple II version of Air Traffic Controller in its late-1979 catalogs and formally announced it as “now available” in January 1980.

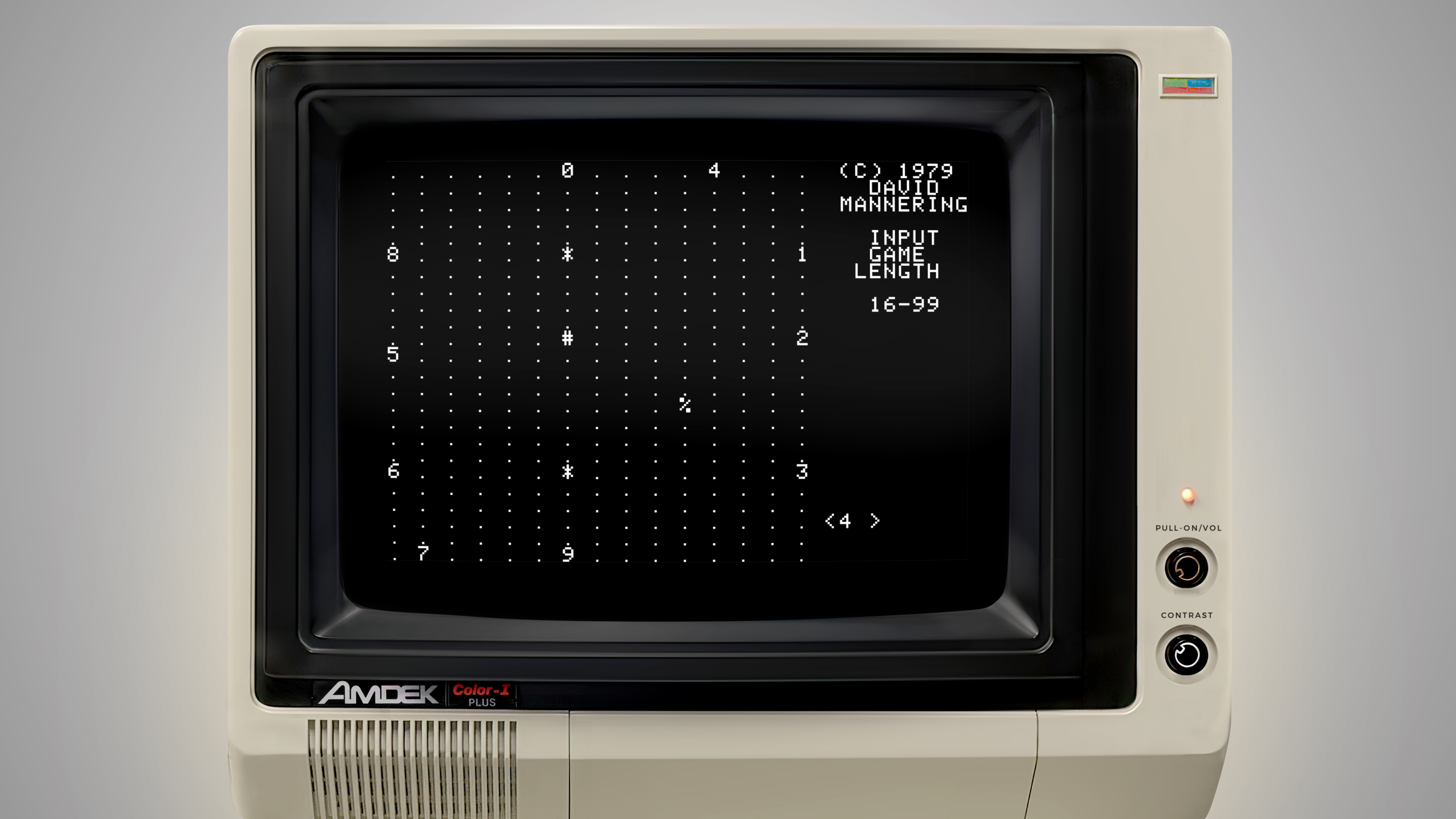

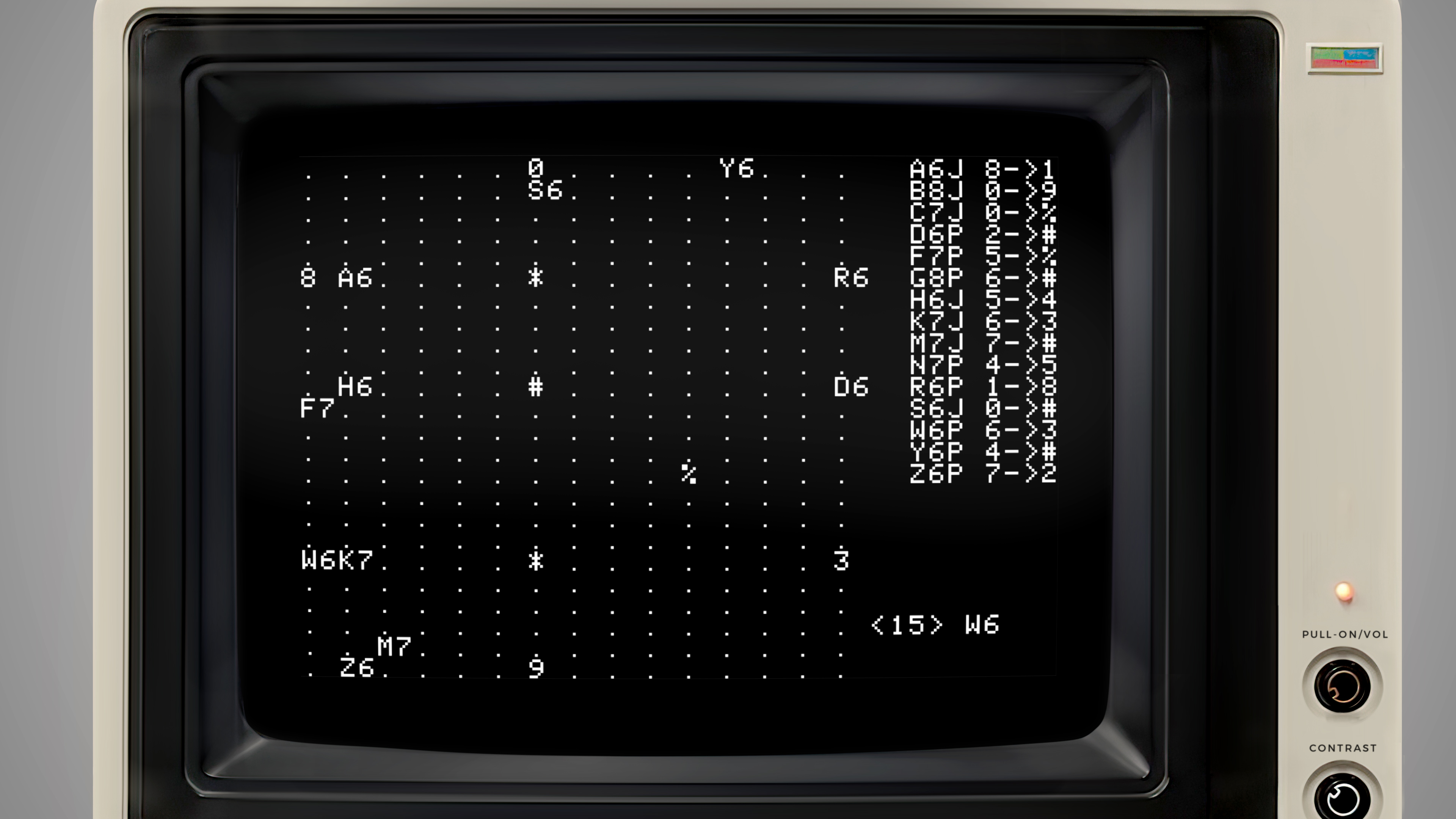

Air Traffic Controller places the player in command of a crowded sector of airspace, overseeing two airports, multiple inbound and outbound aircraft, and a network of navigational beacons. Using abbreviated text commands, players adjust headings, assign altitudes, order holding patterns, and carefully sequence landings, all while preventing mid-air collisions and fuel emergencies. With each radar sweep advancing time, every decision carries weight, and even small mistakes can quickly escalate into disaster.

I usually include a gameplay presentation, but because the game relies entirely on abbreviated text commands and text characters representing the game world, it’s nearly impossible for anyone unfamiliar with the game to follow along. Also, I’m definitely not an air traffic controller. The constant juggling of aircraft and cryptic command syntax made my head explode.

Contemporary reception reflected the game’s seriousness. Reviews acknowledged that Air Traffic Controller was not immediately accessible, but praised it for exactly that reason. It was demanding, methodical, and absorbing, qualities that resonated with players looking for more than diversion.

By 1980, when the Apple II and SOL-20versions had been released, the game had become well-known within home computer circles, earning favorable notice in magazines such as The Space Gamer, which recommended it enthusiastically to owners of compatible systems. Within Creative Computing itself, the game was frequently highlighted as a staff favorite, admired for its realism and originality.

The continued interest led to Advanced Air Traffic Controller, released in 1981, which expanded and refined the original design for a broader range of platforms, including the Commodore PET and Atari 8-bit family.

Air Traffic Controller never became a mass-market hit in the arcade sense, but its influence can be traced forward through the history of simulation games. Later titles, such as Kennedy Approach by MicroProse, would build on Mannering’s foundation, adding speech synthesis, graphical radar displays, and more complex airport operations, but the core idea remained the same.

Sources: Gonnet News Service, The Times, Wikipedia, Internet Archive, Creative Computing, SoftSide…