Across North America, the aftershocks of the video game crash still lingered. The year was 1985, and in the half-decade since its modest birth as On-Line Systems, forged in the living room of Ken and Roberta Williams in Simi Valley, California, Sierra On-Line had come to herald the graphic adventure genre. With Mystery House and The Wizard and the Princess, the company had spearheaded an entirely new frontier with games that dared to fuse text and crude graphics in ways no one had attempted before. Through 1982 and 1983, the future had looked bright, and sales reflected optimism. But dark clouds gathered. The promise of a seemingly limitless action- and cartridge-based market pulled Sierra away from its core strength in personal computer software and into the costly gamble of cartridge production, chasing machines and a market that ultimately proved indifferent.

The promise soon unraveled. The once-booming North American games market collapsed under its own weight of oversaturation and poor-quality products. Warehouses that had once brimmed with excitement now groaned with unsold products, returns, and cartridges stacked like tombstones to a failed gold rush. Sierra’s gamble proved disastrous, sales plummeted, and the company seemed destined to join the long list of casualties. Yet an opportunity from an unlikely corner was already taking shape. IBM, the towering corporate giant of the computing world, had been preparing a bold push into the consumer market, and for that, it had turned to Sierra, setting in motion a partnership that would reshape the company’s future.

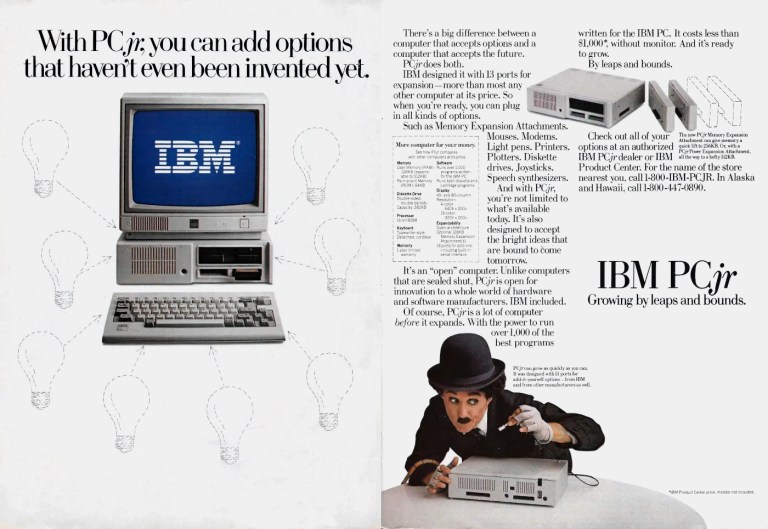

To the world, IBM was the embodiment of corporate austerity, starched collars, large mainframes humming away behind glass walls, a name spoken with reverence in boardrooms. Yet even mighty IBM hungered for a place in people’s homes. Their vision was the PCjr, a sibling to its formidable IBM PC, stripped of its briefcase sobriety and dressed instead for the living room. But hardware alone could not carry the dream. They needed magic, something that could capture a family huddled around a monitor and make them believe that the future was not just spreadsheets and word processors. They needed something to show off the computer’s state-of-the-art graphics and sound capabilities.

Often cited as one of the most memorable advertising campaigns of the era, IBM licensed Charlie Chaplin’s iconic “Little Tramp” character in 1981 from Bubbles Incorporated, S.A., the Chaplin family organization that controls the rights to Chaplin’s work and likeness. The character was portrayed in the commercials by professional mime Billy Scudder. Despite the campaign’s creativity and visibility, its use in promoting the IBM PCjr did little to improve the system’s commercial fortunes.

IBM PCjr advertisement from 1984.

The result of the partnership was King’s Quest (among a few other titles). It was unlike anything the world had seen. For the first time, players were not merely typing commands into static drawings but walked their hero through a living, breathing world. Sir Grahame, the brave knight, ventured across fields, slipped behind castle walls, climbed, and even tumbled headlong into rivers, all in animated, 16-color glory.

At the time, IBM had been in a legal clash with the U.S. Government for over a decade. With the outlook of being split up, the company was afraid of licensing anything exclusively, and King’s Quest was allowed to be marketed to other companies, including Tandy-Radioshack and Sierra On-Line itself. Just as important, the technology developed for it could be used for future projects without the involvement of IBM.

The PCjr itself stumbled. Consumers found it overpriced, underpowered, and a misfit between business and play. But King’s Quest was not defined by the failure of the platform that launched it. It was reborn on sturdier machines like the Apple II, Tandy 1000, and IBM PC compatibles, where its innovation was recognized for what it truly was. For Sierra, it marked the beginning of a new era, one that would cement the company as the leading force in adventure games for the next decade and a half. From King’s Quest, new opportunities emerged, often driven not by executives, but by employees themselves. Among them, two men with a shared love of satire and science fiction: Mark Crowe and Scott Murphy.

Mark Crowe’s journey with Sierra had begun years earlier, in 1982. He had been adrift then, a young man newly unemployed after leaving a printing firm in Fresno, where he had spent his days designing labels destined for grocery store shelves. It was work, but never passion. The future seemed uncertain until a newspaper clipping, rescued and passed along by his mother-in-law, changed everything. A small company in nearby Oakhurst was hiring artists.

Crowe had never touched a computer. His knowledge of games was limited to the flashing cabinets of the local arcade. But something about the idea stirred him. He gathered a portfolio, loaded his car, and drove into the Sierra Nevada foothills. The office he found there was a far cry from the glass towers of the tech industry further west. Sierra’s headquarters, nestled in Oakhurst’s rustic calm, hummed with the unpolished energy of pioneers building something most yet knew how to define. Crowe’s meeting with art director Greg Steffen and marketing director John Williams, Ken’s younger brother, was brief but decisive. They liked his work, and John offered him a position in marketing.

It wasn’t where Crowe wanted to be. He was an illustrator, a dreamer with a sense of humor and a restless imagination. Marketing felt like the wrong end of the telescope. But it was a foot in the door. He bided his time designing packaging, disk labels, and manuals, but his gaze was on the game art department. With the encouragement of fellow artist Doug MacNeill, he began to experiment with Sierra’s in-house tools, the Adventure Game Interpreter, AGI, the framework born out of the IBM PCjr project. Painstakingly, he learned how to translate pen-and-ink into pixels and the sharp angles of vector graphics. Slowly, he found his way into the games themselves, his work first appearing in Winnie the Pooh in the Hundred Acre Wood, The Black Cauldron, and King’s Quest II.

Flip N Match and Creepy Corridors, titles released in 1983 under Sierra’s short-lived SierraVision label. Cover art, designed by Mark Crowe, as some of his earliest works for the company.

Down the hall from the artists’ corner, where vector lines flickered into castles and other fairy tale elements, worked a man who seemed almost out of place in the world of computers. Scott Murphy was a support technician, though “technician” hardly captured his rough-edged charm. He had the dry wit of someone who had spent time in kitchens and bars, not labs and classrooms.

His path into the company was anything but conventional. Murphy had no degree and no formal training. He was raising a family while working long shifts as a cook at a small restaurant in Oakhurst. Opportunity arrived through a chance personal connection, his wife’s acquaintance, Doug Oldfield, a recent hire at Ken and Roberta Williams’ rapidly growing company.

Oldfield carried with him the enthusiasm of Sierra’s world, and one weekend, he invited Murphy over. Sierra had a practice of letting employees borrow computers home, an act of generosity meant to feed curiosity. On Oldfield’s machine, Murphy caught his first glimpse of Sierra’s catalog. He scrolled through the titles, amused, bemused, and then something caught him off guard. Softporn Adventure. Chuck Benton’s irreverent, half-outrageous text game. Crude, brash, absolutely unlike anything Murphy had ever encountered.

The spark it lit was immediate. Murphy began turning up at Sierra’s office more and more, hanging around, asking questions, pestering staff with the stubborn curiosity of someone who wanted in. Eventually, persistence won. Sierra offered him a position, not glamorous, but a start, handling dealer returns. From there, he moved into customer support and disk duplication, whatever job needed hands.

But Murphy was not content to be just another set of hands. His offbeat humor, sharp tongue, and problem-solving instincts set him apart. Ken Williams, who prided himself on spotting raw, unconventional talent, noticed. He encouraged Murphy to tinker, to learn the company’s tools, to try programming in his spare hours. And Murphy did. Soon, the restaurant cook-turned-support tech was debugging code, writing small routines using Sierra’s in-house tools.

During production on The Black Cauldron, Murphy crossed paths with Crowe. By then, Crowe had climbed into the role of Art Director, while Murphy had begun programming on a more regular basis. The two discovered a shared love of science fiction, but not just the serious kind. They loved the grandiose of Star Wars, the optimism of Star Trek, the mystery of 2001: A Space Odyssey, but just as much, they treasured the clever absurdity of Douglas Adams’ Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy.

They began joking, tossing ideas back and forth. What if Sierra made a space game that wasn’t earnest or self-important? What if the hero wasn’t a dashing captain, but the lowest of the low, a janitor, mopping the decks while galactic empires rose and fell? The more they talked, the more the idea had them laugh.

Between official assignments, they were granted the go-ahead to start experimenting. Just a side project, something to amuse themselves. A handful of rooms. A derelict spaceship. An unfortunate custodian stumbling through puzzles and parodies of every sci-fi trope they knew. The humor was sharp, cheeky, unmistakably theirs. When the four-room demo was complete, rather than filter the idea through Sierra’s usual layers of approval, they went straight to Ken Williams.

One afternoon, in 1985, Williams sat down. Crowe and Murphy stood nearby, watching as he guided the janitor through the cramped corridors and rode the whining elevators of their parody world. He read the jokes, solved the puzzles, saw the punchline of an escape plan so catastrophically useless it could only be funny, and he laughed. That was all it took.

It was pure Sierra in those years. Fast, informal, experimental. A sketch, a laugh in the right room, and suddenly a game was born. Now, backed by Williams’ blessing, Crowe and Murphy had the freedom to take their quirky side project and expand it into something larger, a full-fledged adventure that would come to launch one of Sierra’s most beloved series.

The project was christened Star Quest, at least for the moment. With Williams’ approval came something just as precious as office space and development time, a royalty agreement. Negotiated directly with Williams, it tied Crowe and Murphy’s earnings to the game’s sales. For two men who had been tinkering in the margins of Sierra’s empire, it was both exhilarating and terrifying. They were no longer anonymous staffers adding polish to someone else’s vision. For the first time, they were fully in charge, responsible not only for writing and designing but for steering an entire production from beginning to end.

At their disposal was Sierra’s proprietary Adventure Game Interpreter, the technological marvel that had been born out of necessity for the production of King’s Quest. It was a carefully engineered bridge between Sierra’s earlier and rudimentary Hi-Res Adventures and the cinematic future the company envisioned. Written in C and Assembly, AGI introduced a custom scripting language that allowed scenes, objects, and events to be built with unprecedented flexibility. It also made cross-platform development possible in an era when personal computers came in bewildering variety, Apple, IBM, Tandy, and Atari, all with their own quirks and limitations.

But AGI carried the fingerprints of its origin. It was designed with the IBM PCjr in mind, a machine whose compromises still shaped Sierra’s games years after the hardware itself had flopped. IBM had actively marketed the PCjr as a TV-based family computer, and King’s Quest had famously used a 160×200 resolution instead of the PCjr’s full 320×200. It was not an arbitrary choice. It was expected that most PCjr users would rely on composite television sets rather than high-end, expensive RGB monitors. On these displays, higher horizontal resolutions could produce unsightly color artifacts with pixels bleeding, colors shifting unpredictably, and images that looked distorted rather than detailed. The 160×200, using double-width pixels, aligned more gracefully with the NTSC color subcarrier, producing stable, vivid colors that could be reliably enjoyed on a TV screen. A better, richer, and sharper picture, even if the pixels themselves were doubled in width. The technical compromise became somewhat of a trademark, the visual “voice” of early Sierra adventures.

Memory and performance also factored into the decision. The internal 160×200 resolution reduced the frame buffer size, lowered the strain on the PCjr hardware, while allowing smoother animation, quicker redraws, and an overall better experience for the player without being distracted from technical oddities

There were other quirks, too. Artwork wasn’t drawn as bitmaps but painstakingly assembled as programmatic commands, lines, fills, and polygons traced by code. It kept the files small enough to squeeze onto a few floppy disks, but it meant detail was hard to achieve. Rich textures, subtle shading, the kind of fine touches a painter might want, all had to be suggested with the broad strokes the engine allowed. In the wrong hands, AGI could make a game look stiff, simplistic, even childish. But in the right hands, it could sing.

Crowe had the right hands. His experience as an artist and Art Director on The Black Cauldron had taught him the engine’s eccentricities, its hidden strengths, its stubborn weaknesses. With Star Quest, he stretched its limits further, bending AGI toward a retro-futuristic vision. He filled the screen with “neon-lit” spaceships, silhouettes, cartoonish aliens, and planets rendered in bold palettes. Where detail failed him, he leaned into composition and contrast, creating a look that was both clean and confident. The 16-color EGA palette and its rather poor color composition, so often a restraint, became his playground.

Murphy, meanwhile, poured his energy into words. If Crowe gave the game its look, Murphy gave it its voice, a sarcastic one, knowing and utterly unafraid to poke fun at its players. He crammed the parser with pop culture digs, smart-ass replies, and an endless variety of death sequences. The game didn’t just allow you to fail, it celebrated it. Step in the wrong direction, push the wrong button, type the wrong command, and the game would kill you, often in the most ridiculous way imaginable. But before, it rubbed salt in the wound, cracking a joke. You laughed as you died, and then you tried again.

The two of them worked late into the nights, swapping ideas, testing puzzles, revising gags. Crowe sketched alien backdrops, Murphy rewrote parser responses until they snapped with bite. The tone was unlike anything Sierra had done before. Music came from Crowe, too, simple, catchy motifs with a subtle Star Wars resemblance.

As deadlines loomed, Ken Williams himself leaned back into the project. He contributed code, slipped in a few jokes, and lent his weight to push it through the final sprint. More than a manager, Williams acted as the game’s champion. He saw the chance to broaden Sierra’s catalog beyond fairy tales and fantasy, to prove that irreverence could sit alongside majesty. The name, Star Quest, however, would not survive. Sierra’s legal department discovered that the name was already being used, and the project became Space Quest.

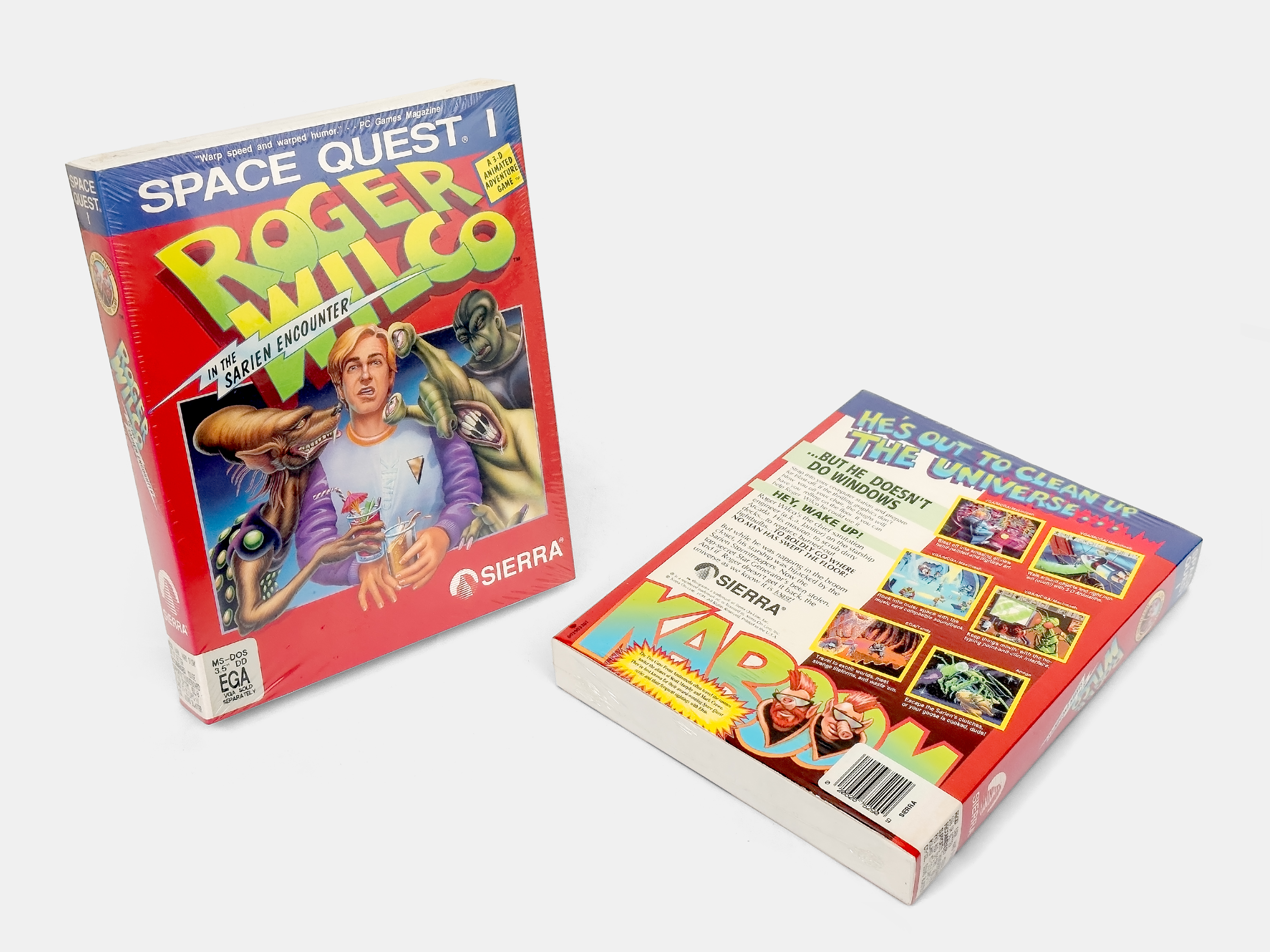

With it, a hero was born. Roger Wilco. The name itself, a clever nod to military radio chatter, “message received, understood, will comply.” He was no king, no knight, no chosen one. Wilco was a janitor, an underdog, a cosmic nobody forever in over his head. Inverting King’s Quest’s noble knight, Wilco was lazy, unlucky, and painfully human. But he was relatable in a way that a storybook monarch could never be. He was an everyman, mocked, battered, and always one step away from a humiliating death.

As the game took shape, the question of how to market such an oddball creation arose. Sierra was accustomed to promoting fairy tales and family-friendly adventures, but Space Quest was different, sarcastic, sometimes happily juvenile. Crowe and Murphy came up with the answer themselves. Playfully, they would refer to themselves not as programmers or artists but as alien emissaries, storytellers from another world. What began as an inside joke in the office, the kind of thing done to blow off steam during long nights of debugging, became an identity.

Soon, the two were dressing up in Sierra’s promotional catalogs as “Aliens from the planet Andromeda”, dressing in colorful wigs and rubber noses. The photos were absurd, but they worked. Fans flipping through Sierra’s glossy brochures suddenly had not just a game, but a story behind the game. Two extraterrestrial pranksters delivering their spacefaring janitor’s misadventures straight from across the cosmos.

The joke became a brand. Crowe and Murphy were no longer simply Mark and Scott. They were “The Two Guys from Andromeda.” The personas gave them cover to push their writing further into parody, to stuff the game with inside jokes, pop culture riffs, and a kind of winking self-awareness that felt fresh in the mid-1980s. For Sierra, the alter egos became a marketing goldmine, part creative signature, part comic shield.

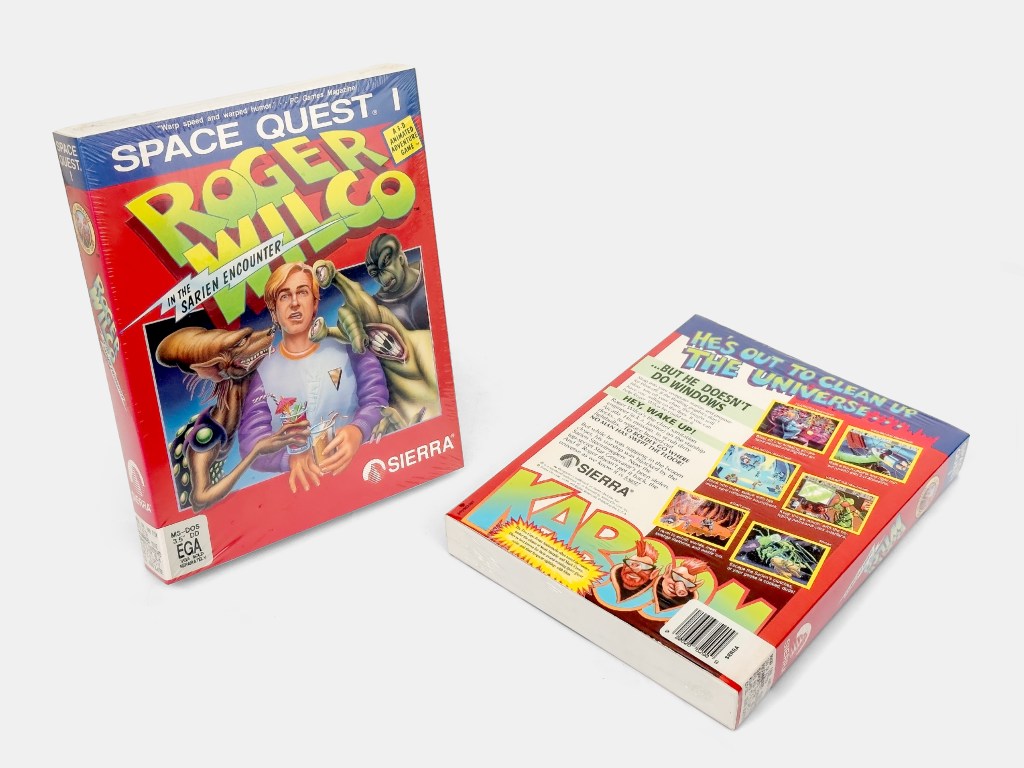

By the autumn of 1986, the work was finally done. Roger Wilco was ready to stumble his way into the galaxy. After countless revisions, marathon nights, and steady streams of pizzas, Space Quest: Chapter I – The Sarien Encounter was complete. It shipped first for the IBM PC, PCjr, and compatibles, running on the updated AGI2 engine. What had begun as a four-room joke had grown into a full adventure, packed with obscure aliens, planets, slapstick humor, and death screens that happily mocked the player’s every misstep.

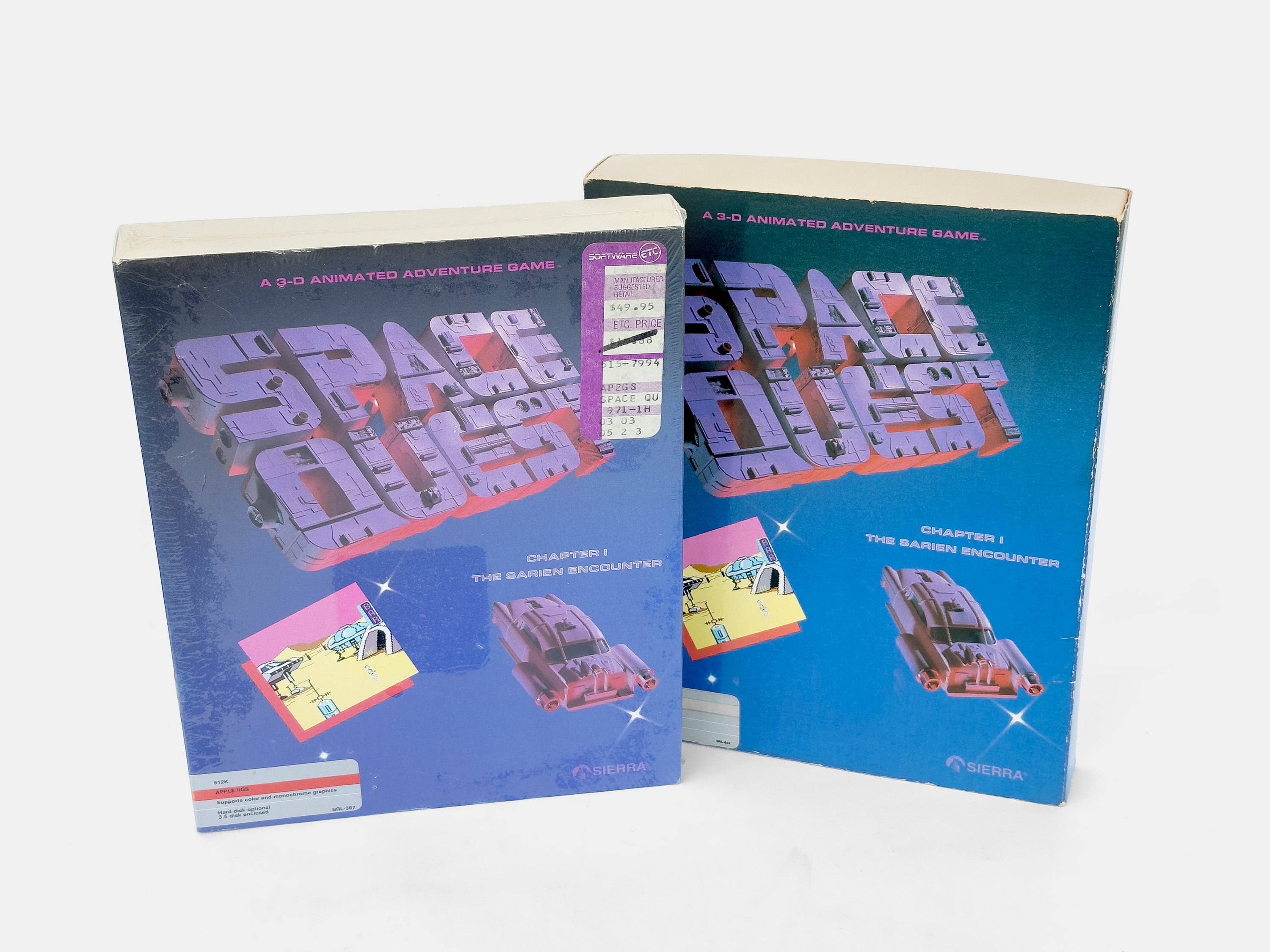

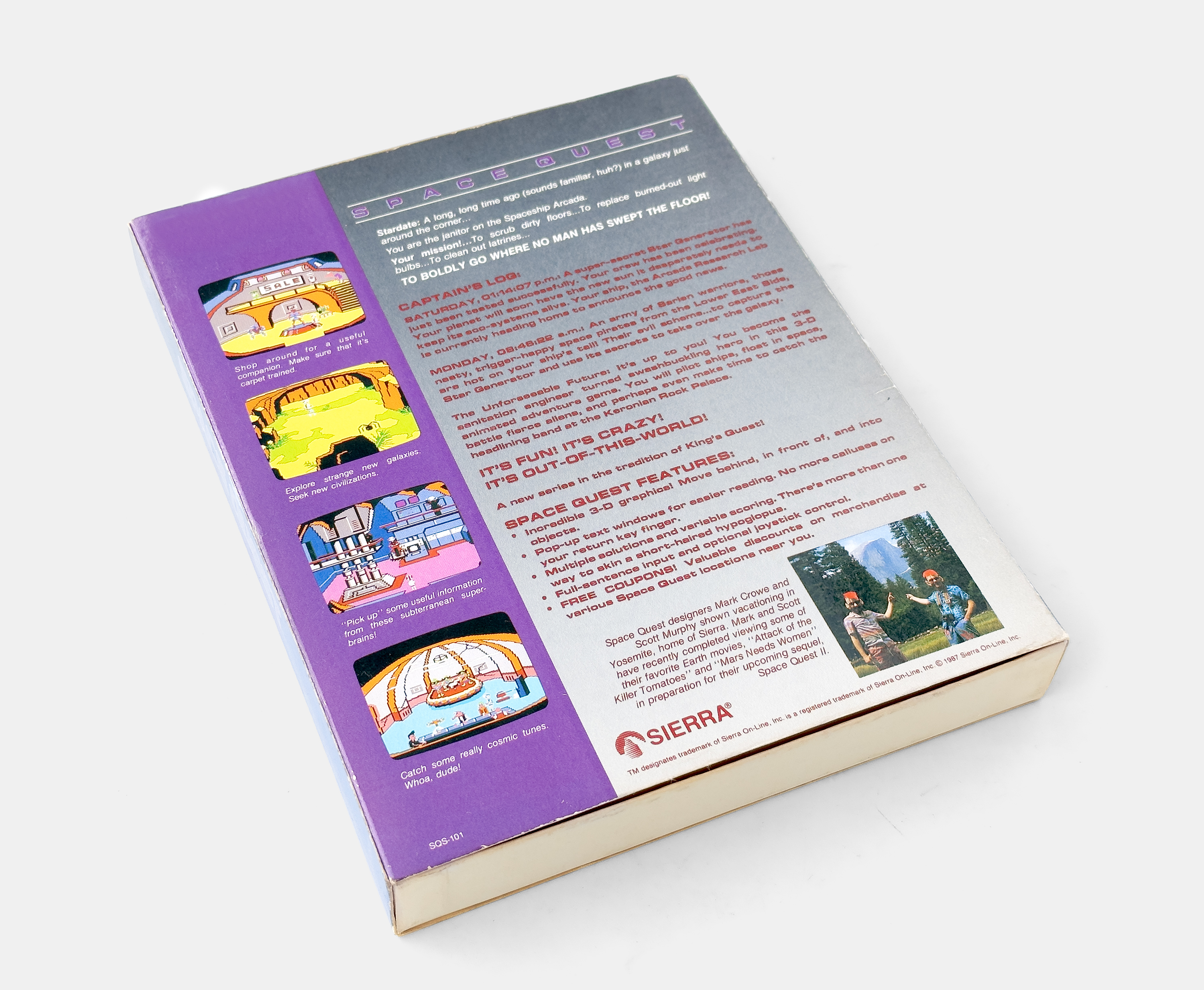

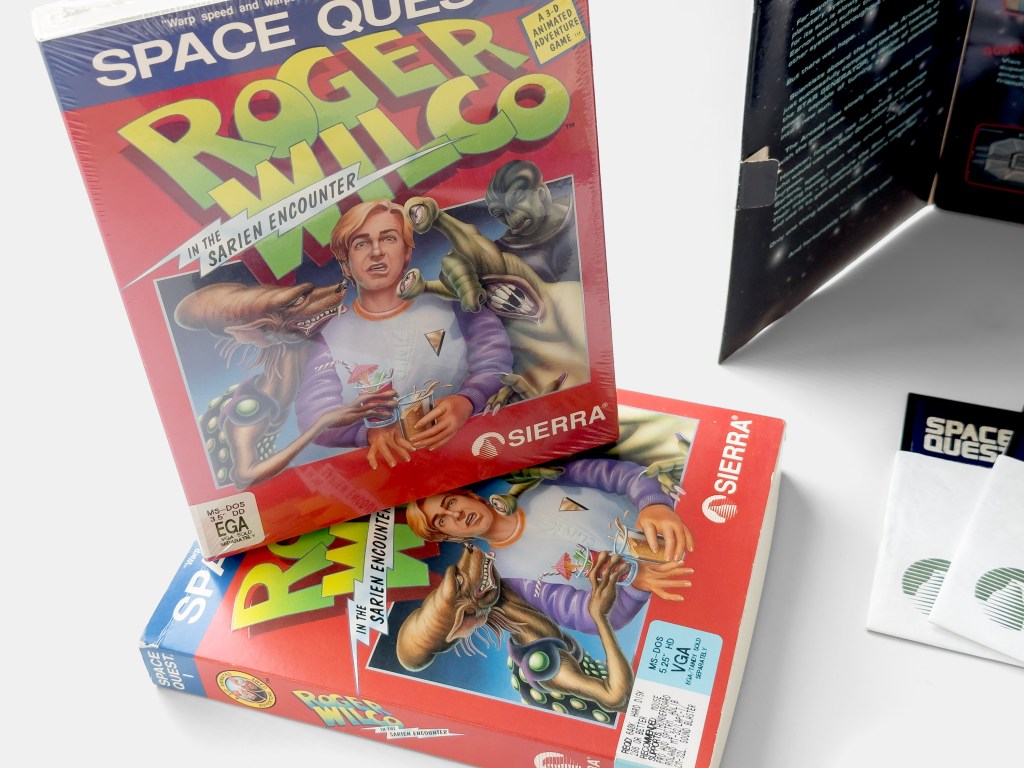

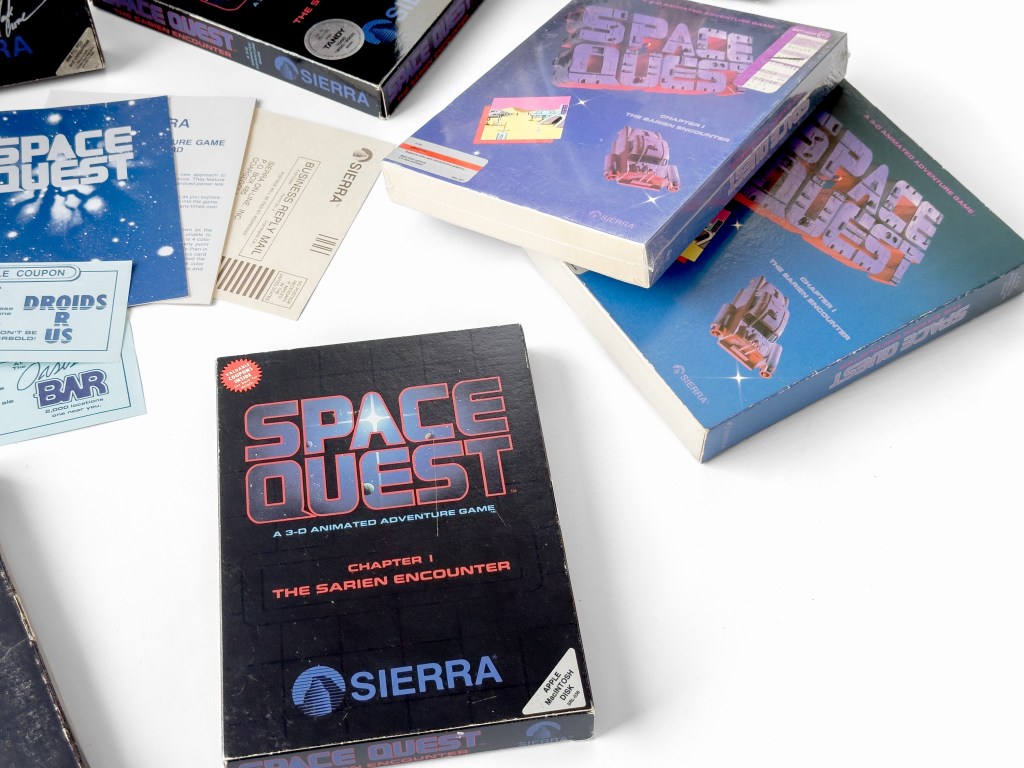

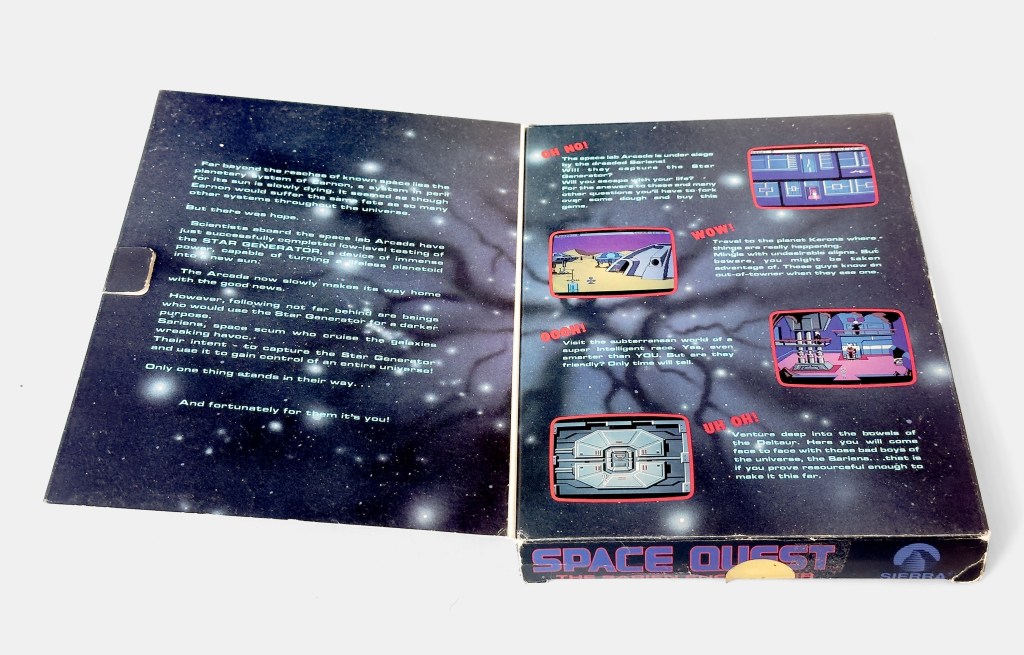

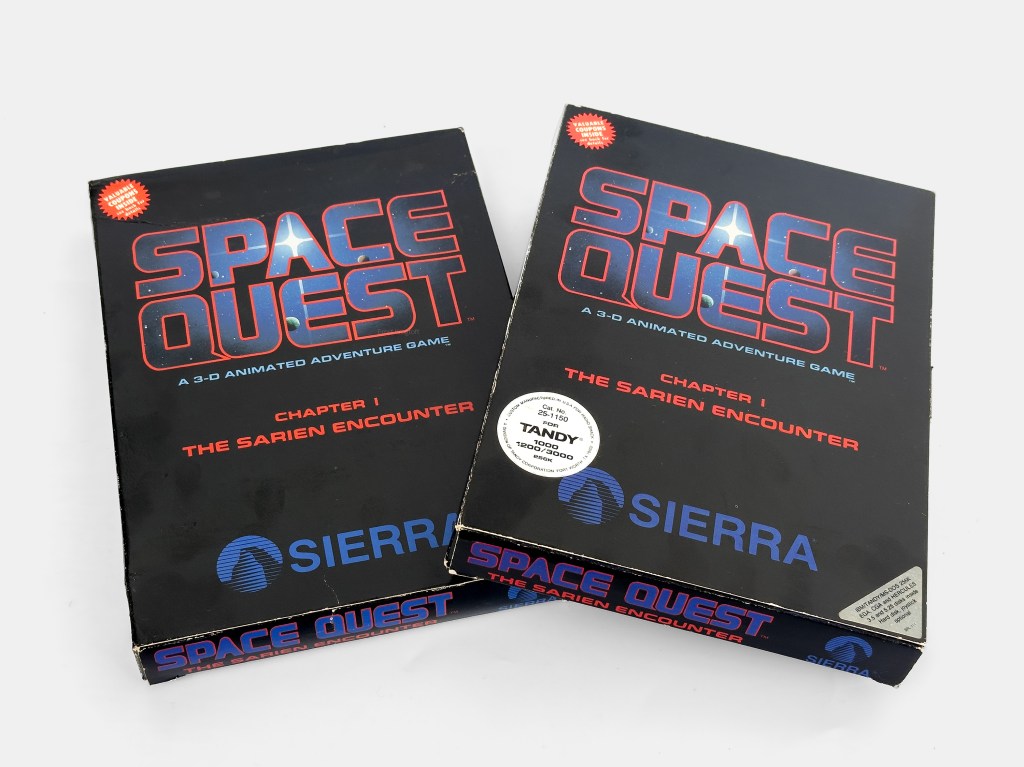

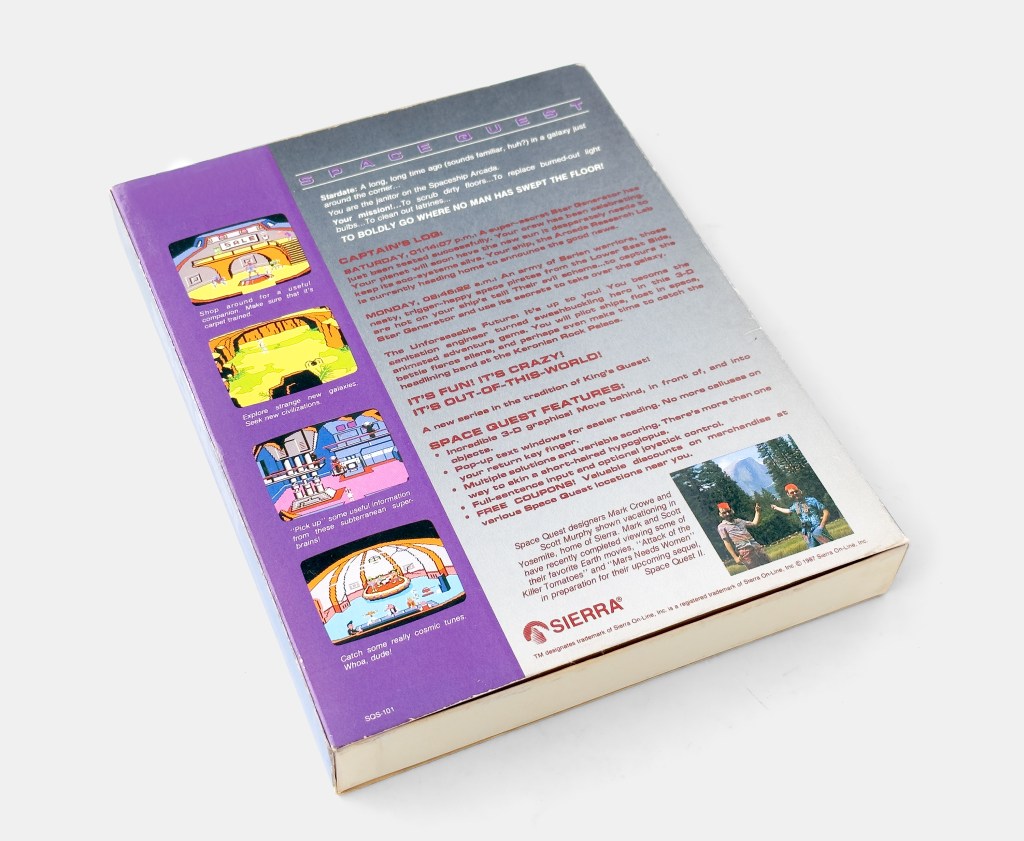

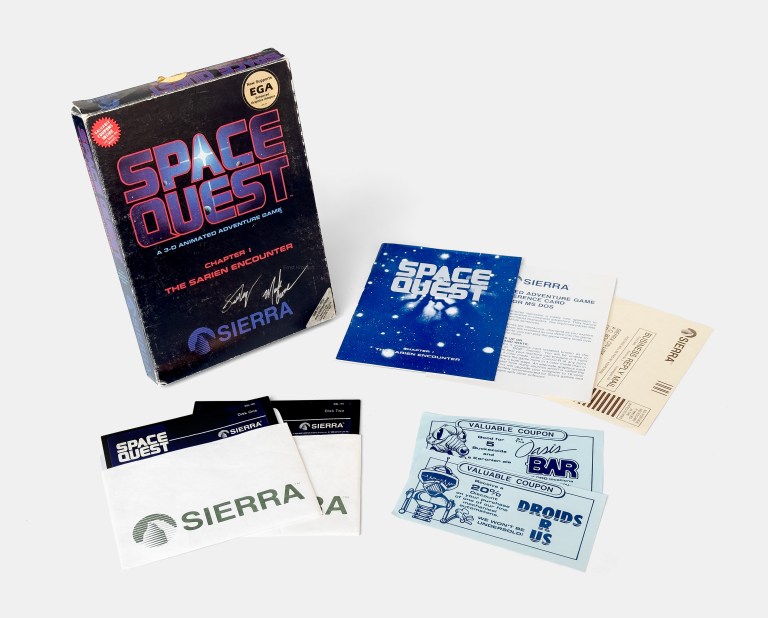

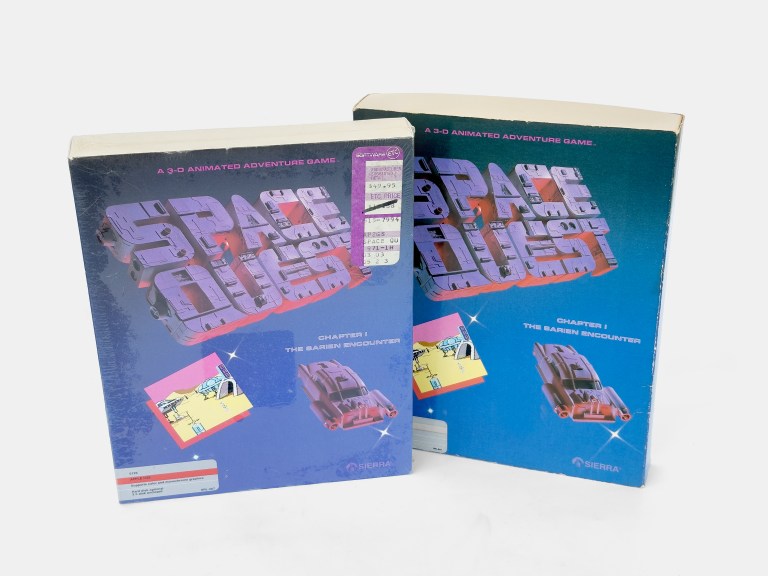

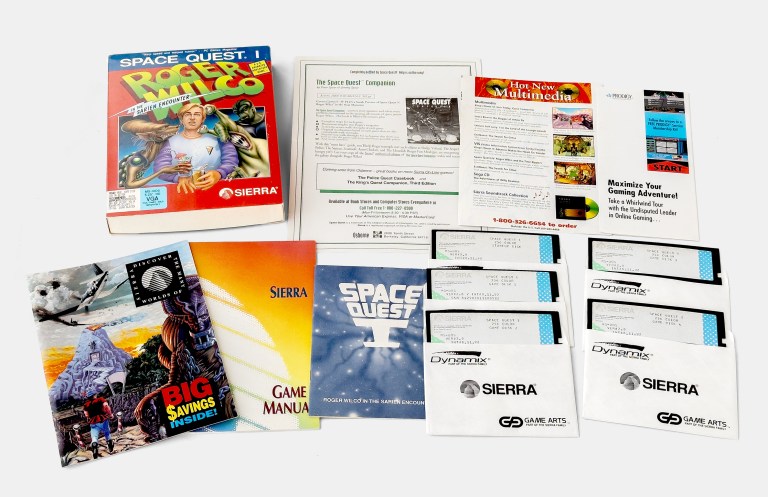

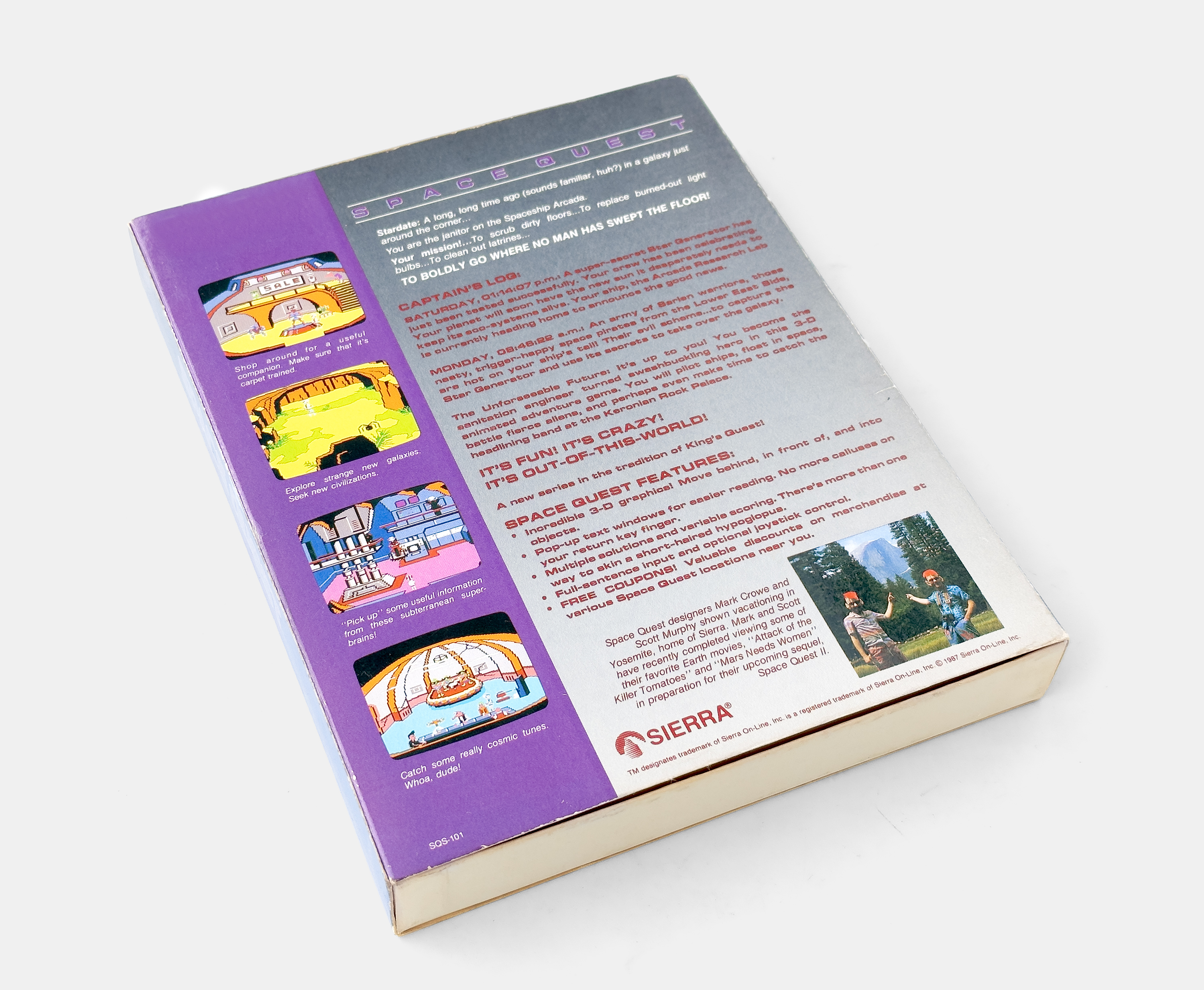

Space Quest: Chapter I – The Sarien Encounter shipped in October 1986 for the IBM PC, PCjr, and compatible systems. The original black gatefold box with a subtle grid overlay on the cover included two 5.25″ floppy disks, a 16-page manual, a reference and registration card, and two “valuable” coupons for the Galaxy-wide chain of stores, Droids R Us, and the Oasis Bar.

As a low-ranking sanitation worker aboard the spaceship Arcada, Roger Wilco finds himself the sole survivor after a Sarien attack, now with the all-important Star Generator missing. What follows is a galactic misadventure through derelict ships and desert planets. The humor is sharp, often meta, with constant jabs at sci-fi tropes, pop culture, and Sierra’s own style of puzzle design.

Like King’s Quest, Space Quest was ruthlessly punishing, with death only a command away. Type the wrong word or take one step too far, and Roger would meet an instant, and often comical, demise.

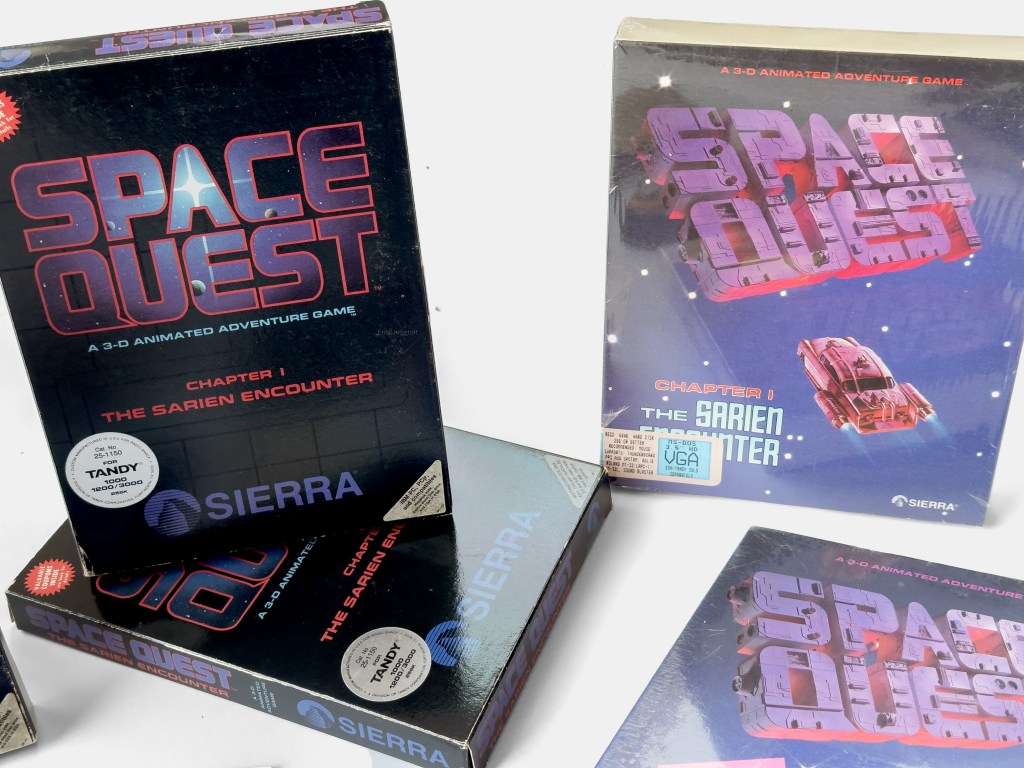

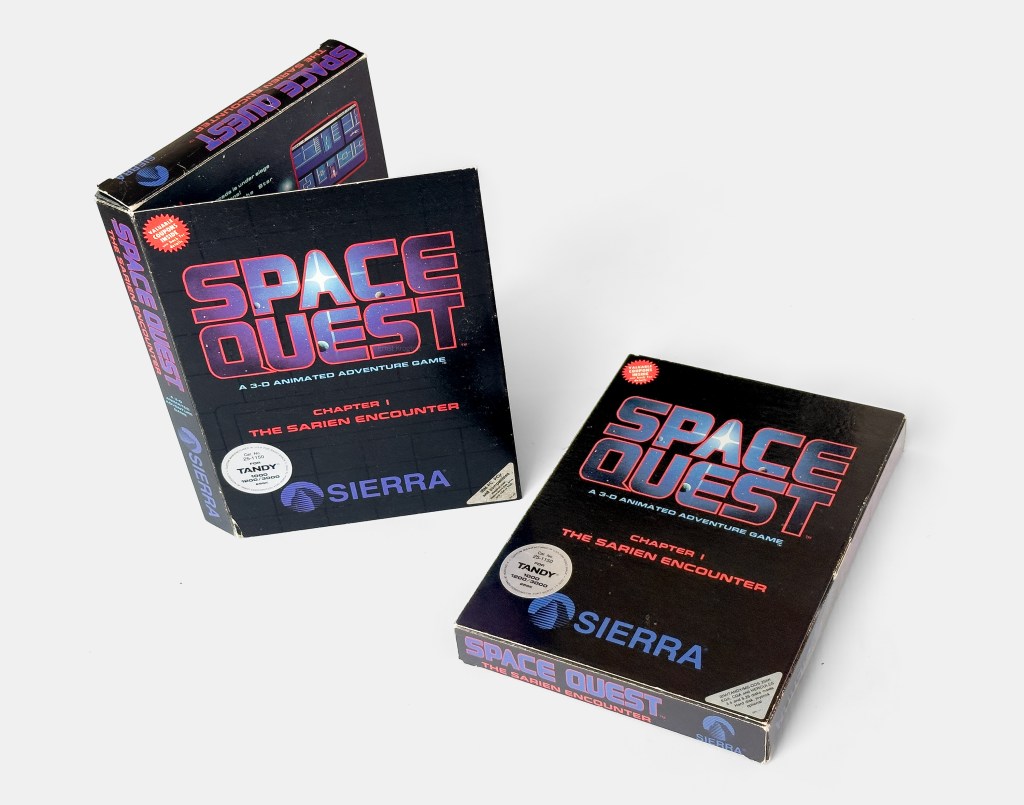

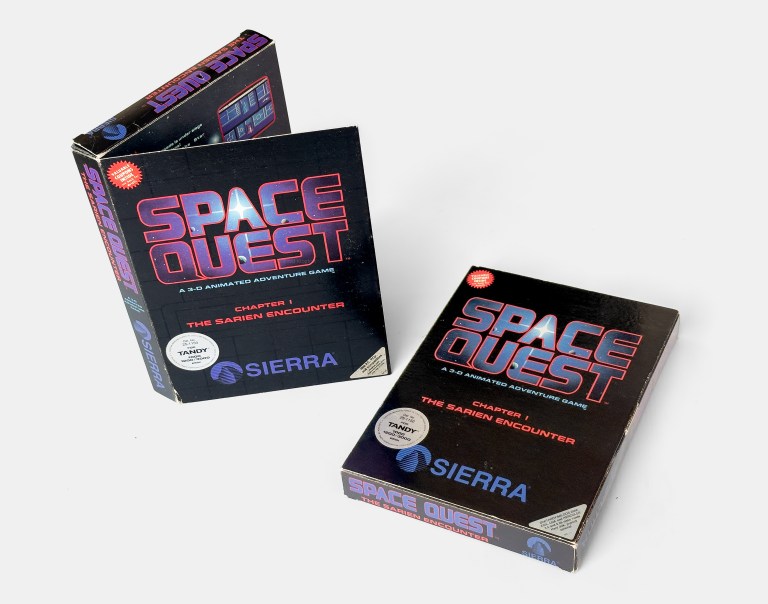

The IBM PC version, like all Sierra titles of its time, relied on the humble PC speaker for sound. Its real showcase was the 16-color EGA graphics, which gave Space Quest the same vibrancy that IBM’s ill-fated PCjr had once promised. But in 1986, few players could afford the luxury of EGA. Most were still confined to four-color CGA cards, their spaceports reduced to cyan skies and magenta shadows. It wasn’t until the close of the decade that EGA trickled into the mainstream. In the meantime, the unlikely champion of Space Quest was Radio Shack’s Tandy 1000, a machine that succeeded where IBM’s PCjr had stumbled. Affordable, compatible, and equipped with both 16-color graphics and a three-voice sound chip, the Tandy delivered the game as Crowe and Murphy had intended, with vibrant visuals and jolly music that elevated the janitor’s cosmic misadventures.

The first prints featured a faint printed grid overlay on the cover, which was abandoned on later releases.

When Space Quest reached store shelves in late 1986, it sold modestly, at first. It didn’t rival the numbers of the latest arrival in the company’s flagship series, King’s Quest III: To Heir is Human, which launched the same holiday season, but something about its irreverent tone stuck. Critics called it “a refreshing change of pace” and praised its parser wit and colorful art. Fans, particularly players raised on Star Wars and Star Trek, devoured it. Letters poured into Sierra, demanding more of Roger Wilco. Word of mouth did the rest. The jokes and absurd death scenes were repeated in playgrounds, computer clubs, and bulletin boards. What Sierra had intended as a quirky experiment was quietly becoming a phenomenon.

In late 1986, an updated version of Space Quest was distributed by Radio Shack and sold in thousands of the chain’s stores across the US. This edition retained the subtle grid pattern on the front cover (left).

By 1987, a new reissue appeared, now including the game on 3.5″ floppy as well, with a cleaner box design, dropping the grid entirely (right).

The game version was upgraded to 1.1a to be more compatible with the IBM PCjr and early Tandy 1000 models, as both, unlike the IBM PC, lacked a dedicated DMA controller, relying on the video chip for memory refresh.

With parody came pitfalls. The game was laced with inside jokes and pop-culture references, some of them a little too close for comfort. In Ulence Flats, players could enter the Oasis bar and find pixelated bands performing on stage. Among them were unmistakable caricatures of The Blues Brothers and ZZ Top. It was a throwaway gag, randomized by the game’s internal clock, but it caught the wrong kind of attention. Reportedly, Sierra soon received a stern notice, likely from ZZ Top’s representatives, objecting to the unauthorized likenesses. The decision was swift, and future releases would strip out the band entirely.

A similar fate befell “Droids R Us,” a parody of the toy giant Toys “R” Us. The original release of the game included a fictional galaxy-wide chain of stores called “Droids R Us”, both as an in-game location and prominently featured in marketing materials, including a physical coupon that came with the game. It was a clever extra, part of Sierra’s trend at the time to include physical props or documents to enrich the experience of owning an authentic copy. The name was a tongue-in-cheek parody of the popular toy retailer. However, the joke didn’t sit well with the retail giant, whose legal team contacted Sierra with a cease-and-desist order over trademark infringement. Facing the threat of a costly legal battle, Sierra quickly complied. The Droids R Us name was removed and replaced with the more neutral “Droids B Us”.

Space Quest received a quick round of minor bug fixes, with updated versions issued on both 5.25″ and 3.5″ floppy disks. The original packaging’s faint grid overlay was quietly dropped, due to cost and possible aesthetic concerns. Meanwhile, the in-box Droids R Us coupon was rebranded as Droids B Us, though some copies with the original version continued to circulate.

The Original and revised in-box coupons.

The first version, Droids R Us, a clear parody of Toys ‘R’ Us, was replaced with the more neutral Droids B Us following legal pressure from the toy retailer.

Despite legal headaches, sales climbed. By the end of its first year, Space Quest had sold more than 100,000 copies, an impressive feat for a niche adventure. It performed especially well on the IBM PC and Tandy 1000, platforms Sierra was increasingly prioritizing after its profitable IBM partnership. The janitor had found his audience, and Sierra took notice. Crowe and Murphy, now firmly established as “The Two Guys from Andromeda,” were promoted to full-time designers, and a sequel was fast-tracked for 1987.

While the initial IBM PC, Tandy, Apple II, and Atari ST versions all appeared in 1986, the Macintosh version (along with the Commodore Amiga version) didn’t ship until the following year. Some Macintosh copies still used the earlier black box featuring the faint grid overlay on the cover and retained the “Droid R Us” coupon, reflecting inventory pulled from earlier print runs. The Macintosh AGI build was unique as it lacked color support and featured a menu-driven interface.

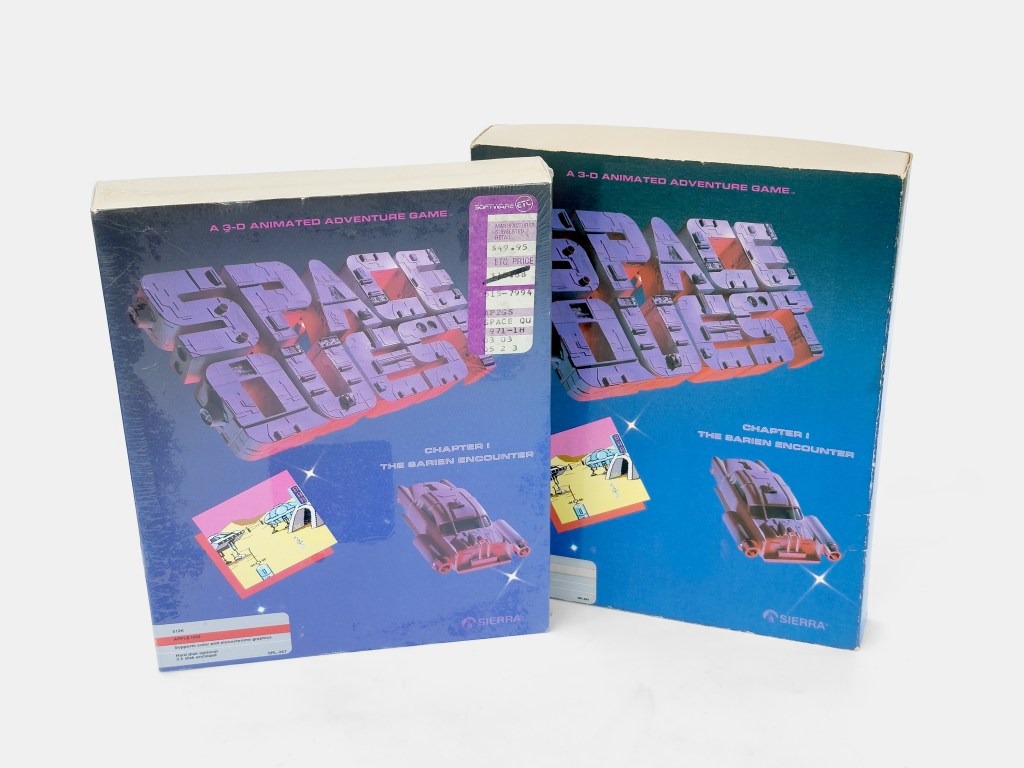

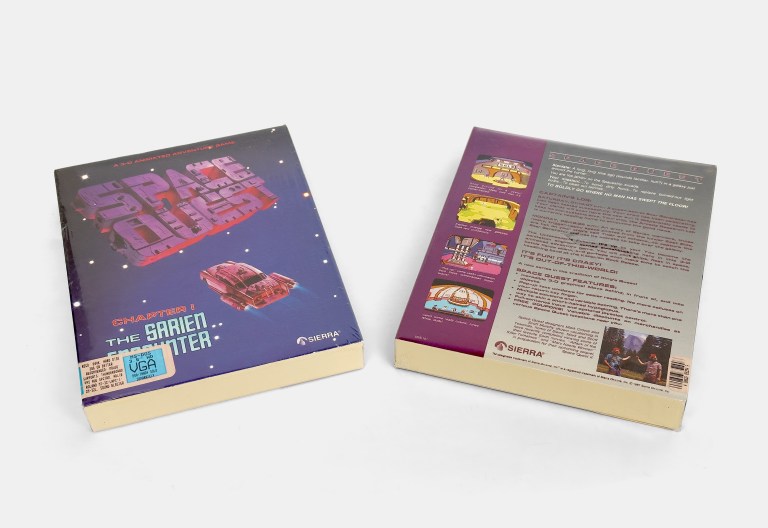

By late 1986 and into 1987, Sierra was evolving its identity. The ornate gatefold packaging of earlier releases was phased out in favor of a more standardized slipcase box, upright, sturdier, and designed to create a consistent presence on retail shelves, and at the same time reduce packaging costs. The change coincided with broader efforts by the company to unify its brand presentation across a growing product line. Space Quest was among the first to be reissued in the new format, with version 2.2 featuring various bug fixes and minor improvements over earlier releases.

The first slipcase edition of Space Quest was introduced in 1987 and featured a screenshot displayed prominently on the front cover.

All new slipcase versions came with the “Droid B Us” coupon.

For the Apple IIGS version, Al Lowe reworked the score into richer arrangements. Lowe, of course, would soon become infamous in his own right as the mind behind Leisure Suit Larry, another Sierra series that mixed comedy with risk.

The first few thousand copies retained the same photo of Yosemite’s iconic Half Dome on the back, as seen in the original gatefold release, but was mistakenly mirrored, a production oversight that was quickly corrected.

In the Sierra Newsletter Volume 1, No 2, from late 1987, the mistake was mentioned, calling out collectors.

In the fall of 1988, Sierra introduced a revised slipcase edition that leaned into a cleaner, more polished look.

In 1991, Sierra revisited Space Quest with a VGA remake, part of a wider push to modernize its back catalog with its newer Sierra Creative Interpreter framework. The updated Space Quest I featured 256-color graphics, mouse controls, enhanced sound, and a lightly revised script. It was ambitious, but costly, remakes demanded nearly as much work as new games, and by then Sierra’s attention was shifting to blockbuster originals like King’s Quest V and Space Quest IV. Only a handful of the planned remakes were completed before the strategy was abandoned.

The 1991 VGA remake of Space Quest featured updated 256-color graphics with the game world being completely redrawn, replacing the original AGI vector-style artwork. A fully point-and-click interface, animated cutscenes, and newly recorded music, all part of Sierra’s brief initiative to modernize select classics for a new generation of gamers.

The remake also received an EGA release, featuring redesigned 16-color graphics, hand-tuned to preserve the remake’s updated look while working within the limitations of EGA hardware.

The 1991 remake infused Space Quest with a retro-futuristic style, blending 1950s pulp sci-fi with late-1980s space-opera aesthetics. It brought the game fully into Sierra’s VGA era, replacing the original’s blocky, vector AGI graphics with hand-painted backgrounds, smoother animations, and a complete mouse-driven interface. The core puzzles remained unchanged, but everything else, from the controls to the visual storytelling, reflected five years of technological progress.

As the ’80s drew to a close, the Space Quest series had sold over half a million copies, its first installment accounting for a large share. More than sales, though, it had proved that adventure games could be funny, self-aware, even anarchic. Death could be a punchline, and the parser could be a playground for satire as much as problem-solving.

For Crowe and Murphy, it was the beginning of a partnership that would carry them through sequels, conventions, creative clashes, breakups, and eventual reunions. But in those early years, they were simply two Sierra employees who had stumbled into a winning idea. A galactic janitor who would become one of gaming’s most unlikely icons.

Perhaps more than any other title, Space Quest embodied Sierra’s willingness to laugh at itself. Between the chivalry of King’s Quest and the hard realism of Police Quest, it opened the door to stranger, sillier experiments. Its spirit would live on not just in its own sequels, but in the antics of Leisure Suit Larry and the satirical wild west of Freddy Pharkas: Frontier Pharmacist.

Sources: Adventure Gamers Interview with the Two Guys From Andromeda, Ken Williams: Not All Fairy Tales Have Happy Endings, InterAction Magazine, Wikipedia, Digital Antiquarian, Sierra Newsletter Volume 1 Number 2, The Sierra Chest, Shawn Mills: The Sierra Adventure – The Story of Sierra On-Line, Stephen Emond: Sierra Collectors Quest…