Chuck “Chuckles” Bueche, best known as a co-founder of Origin Systems, made a small name for himself in the early 1980s with a series of action-oriented games. His journey into game development was largely influenced by his college roommate at the University of Texas, Richard Garriott, better known as “Lord British,” the creator of the Ultima series. Through their shared passion for computing, Bueche was introduced to the emerging world of home computers, something that would shape his career.

The personal computer revolution of the late 1970s and early 1980s was a wild frontier. Across the United States, hobbyists were transforming computers from technical curiosities into something far more personal and expressive. The era spawned names that would become legends, Garriott among them, while others burned just as brightly in their shadows. Bueche was one of those.

Raised in Texas and drawn to electronics from an early age, Bueche met Garriott at the University of Texas in Austin, where they became roommates and collaborators. As a freshman in 1980, Garriott’s enthusiasm for computers proved contagious, and soon Bueche acquired his first machine, an Apple II. While Garriott was busy crafting the fantasy worlds that would evolve into the Ultima series, Bueche was absorbing the technical fundamentals that would later define his own contributions to the emerging personal computer landscape.

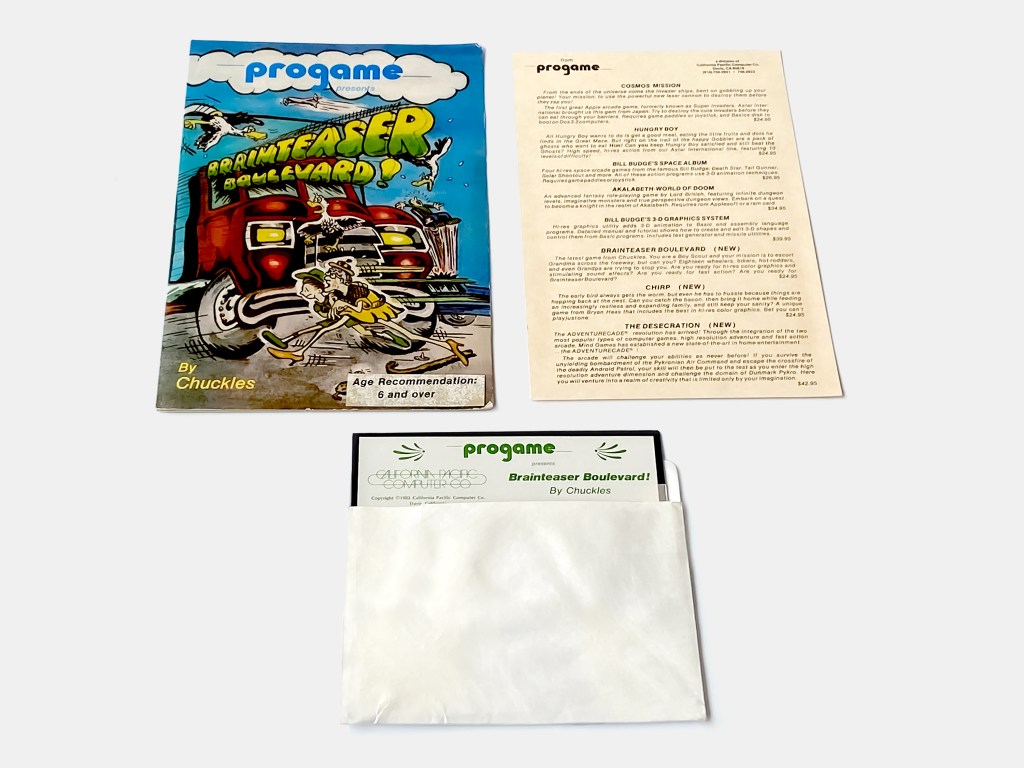

In 1981, Bueche released his first commercial title, Brainteaser Boulevard!, a simple Frogger-inspired arcade game published by California Pacific Computer Company, the same company that had brought Garriott’s first game, Akalabeth: World of Doom, and soon Ultima I, to market. Al Remmers of California Pacific played a crucial role in helping both young developers establish themselves in the industry, though the company would soon fold. That setback did little to slow them, and both soon found themselves working with Ken and Roberta Williams’ On-Line Systems, setting both on trajectories that would define lifelong careers in gaming.

Chuck Bueche’s first game, Brainteaser Boulevard!, was published for the Apple II by California Pacific Computer Company in 1981, the same company that had picked up Richard Garriott’s Akalabeth and Ultima.

The game was signed by “Chuckles,” a nickname that Bueche had picked up in high school.

The following year, Bueche developed Laf Pak, a collection of four small arcade-style games. Creepy Corridors, Apple Zap, Space Race, and Mine Sweep, simple and fast-paced titles reflecting the trends dominating the arcade market at the time. The collection was released through On-Line Systems, which had also signed Garriott for his upcoming Ultima II: Revenge of the Enchantress.

Chuck Bueche’s second published title, Laf Pak, was a compilation of four small action games, published by On-Line Systems in 1982.

Each of the titles reflected gameplay of some of the most popular games of the era

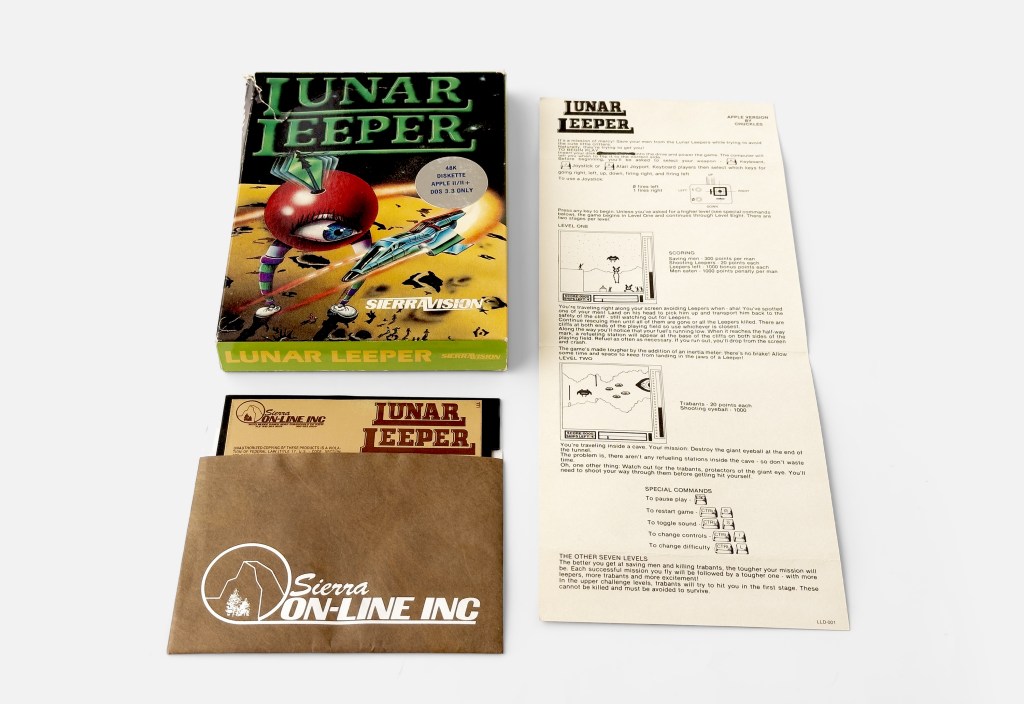

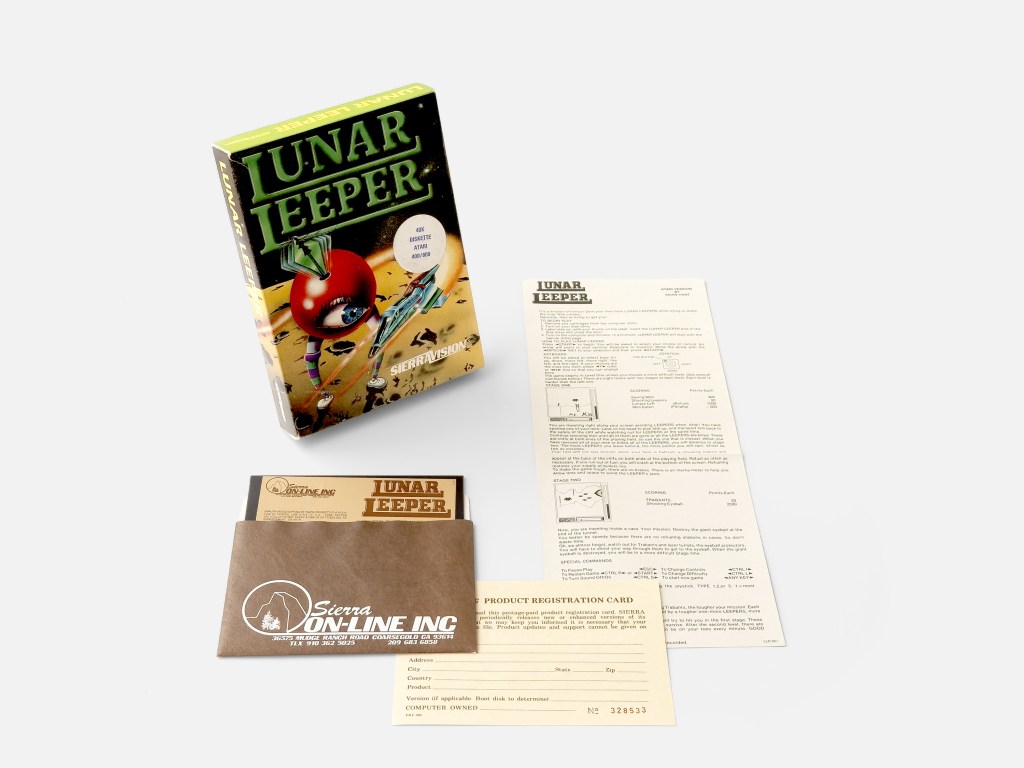

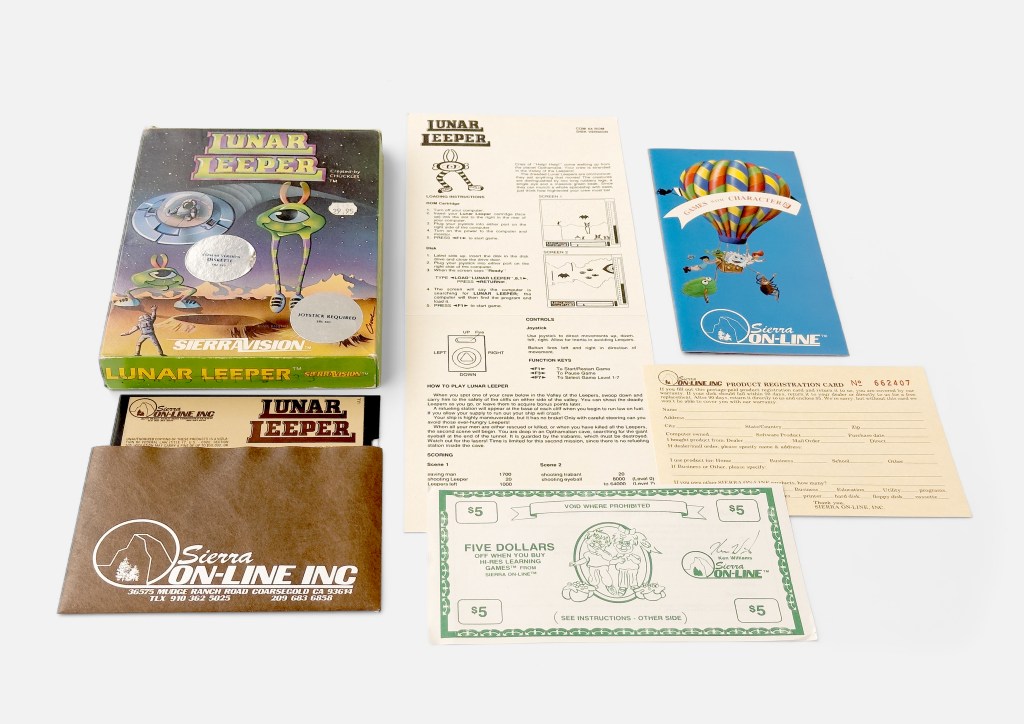

By 1982, On‑Line Systems was preparing the next big corporate step. Investment, a million dollars from investor Jacqueline Morby of prestigious TA Associates, led to a revamped identity. Now, as Sierra On‑Line came, a rethinking of how the company marketed its diverse range of software. That autumn, Sierra introduced SierraVision, a brand aimed squarely at action and cartridge-based games. While Sierra’s adventure titles, released under the SierraVenture label, were building a reputation for storytelling and visual flair, SierraVision targeted players who craved fast reflexes and arcade excitement across a wide range of machines.

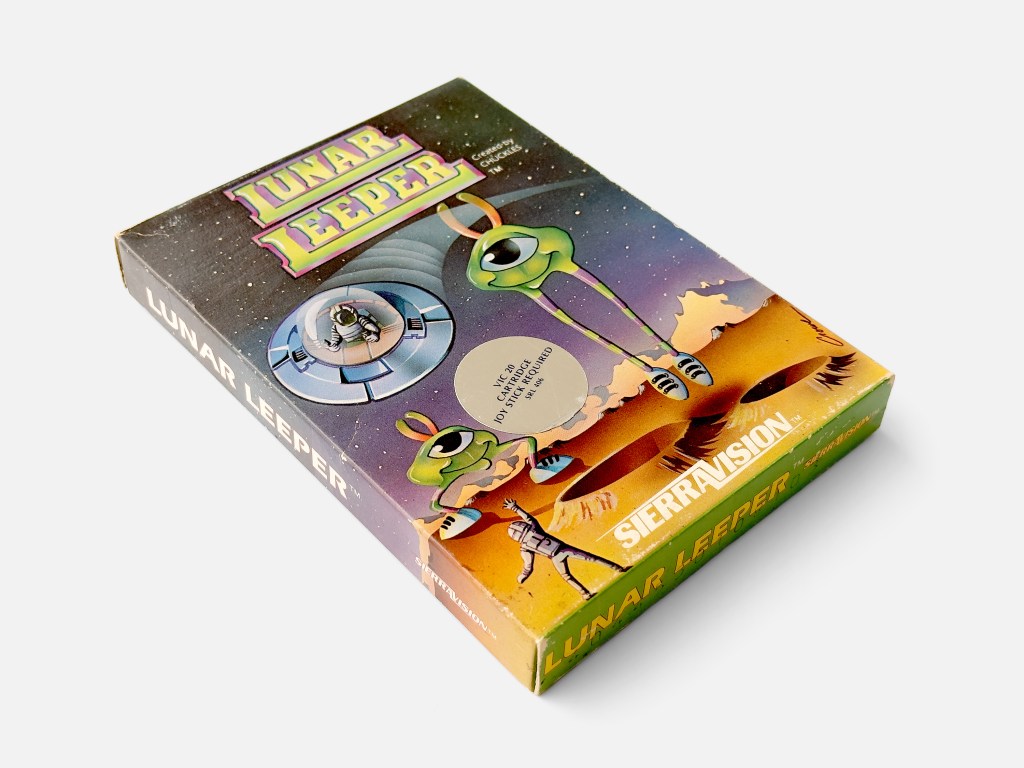

Amid the transition within Sierra, Bueche was hard at work on his next project, Lunar Leeper, a side-scrolling action game that blended elements of Williams Electronics‘ Defender with its own unique twists. Despite Ken Williams’ minimal interest in playing games himself, he admired Defender‘s technical ingenuity and saw potential in Bueche’s work. Lunar Leeper challenged players to navigate a spaceship across a hostile alien landscape, dodging deadly tentacled creatures, called Leepers, while rescuing stranded colonists before escaping to safety.

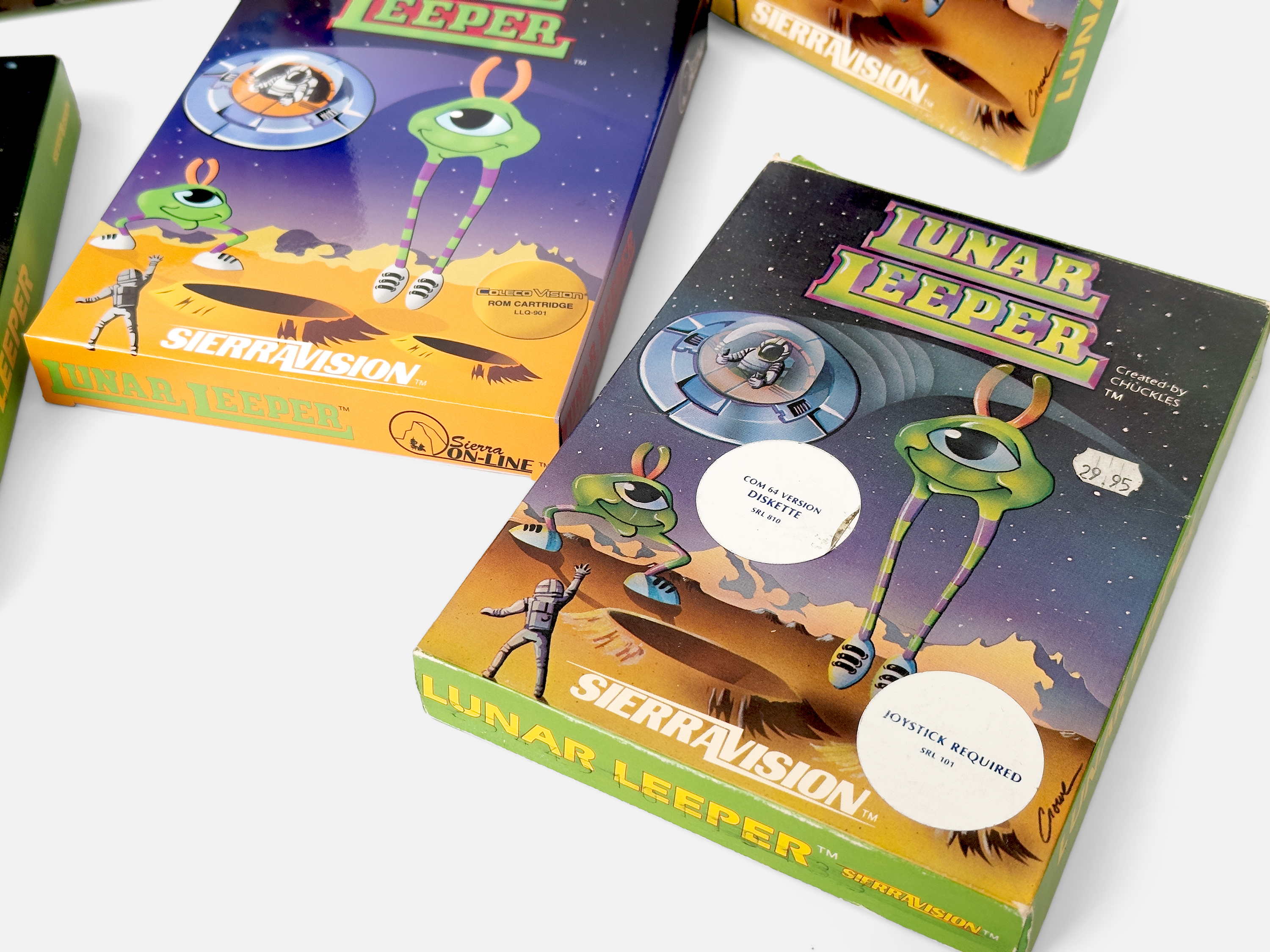

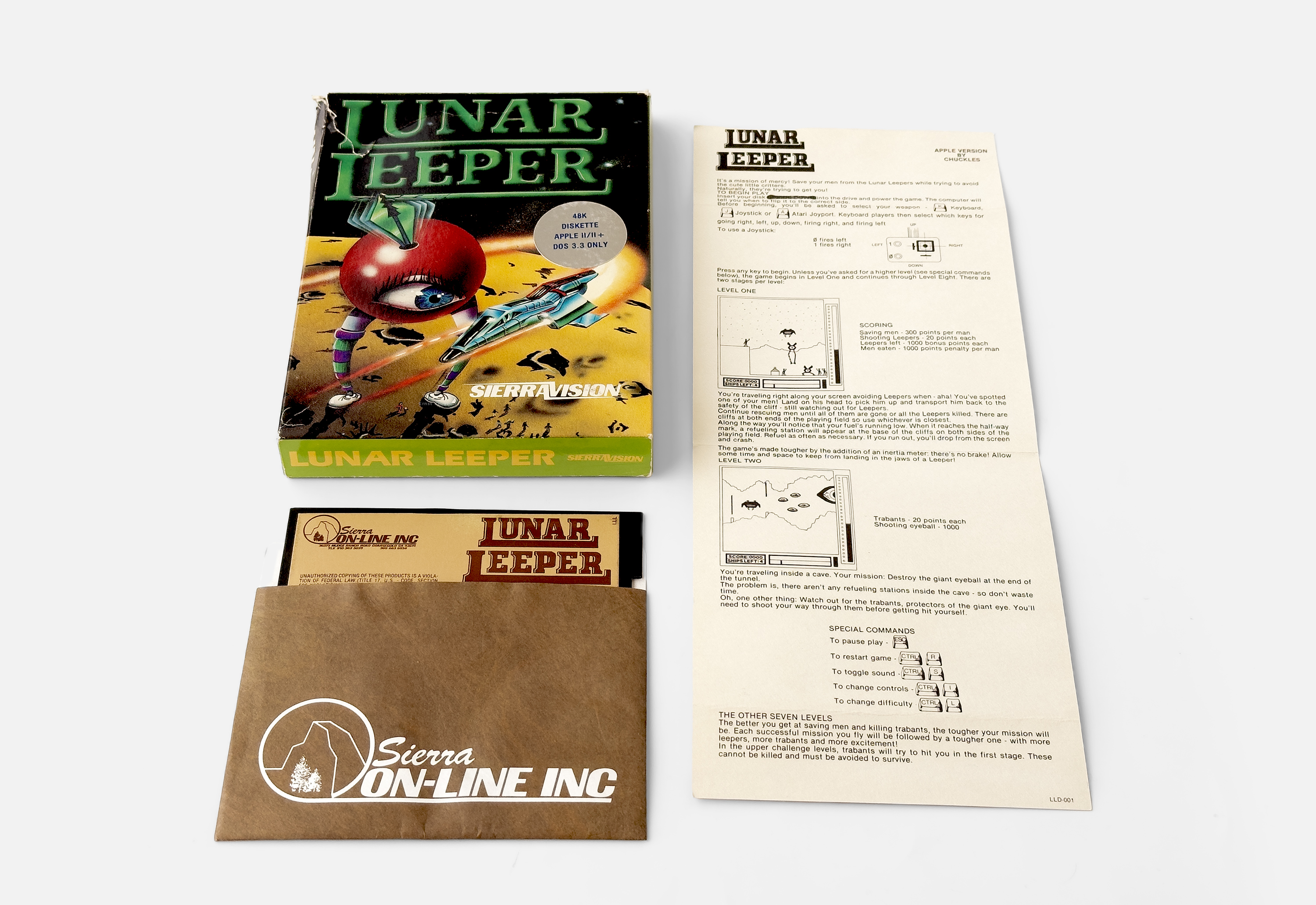

Chuck Bueche’s Lunar Leeper was released for the Apple II in late 1982 as part of the first batch of games under Sierra On-Line’s newly established, but short-lived, SierraVision label. The backside of the box and the title screen referred to the game as Lunar Leepers (instead of Lunar Leeper).

Lunar Leeper carried with it all the hallmarks of early arcade influence, with side‑scrolling action and missions that could be grasped in seconds but mastered only through repetition. The game features two scenes, one above the lunar surface and one below. Piloting a lunar lander, your mission on the surface is to rescue stranded astronauts while dodging or shooting leaping aliens, known as “Leepers.” Underground, you have to be quick, avoid lasers and the treacherous cave walls, and destroy a giant eyeball. The gameplay combines elements of precision flying with increasing difficulty as players progress through the two looping levels.

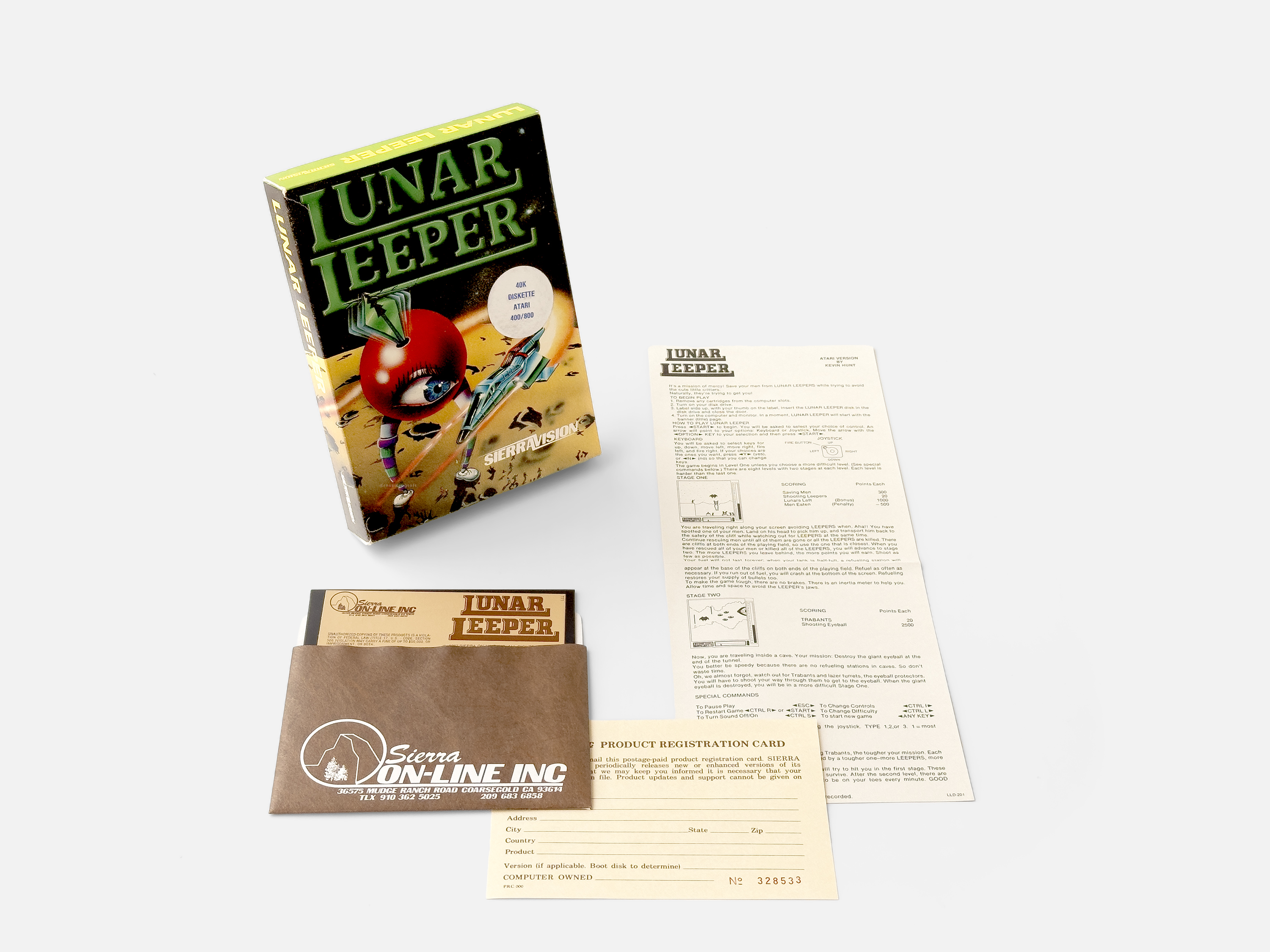

Leveraging Sierra’s growing expertise in software publishing and trying to accommodate most systems of the era, subsequent ports to the VIC‑20, Atari 8‑bit, and Commodore 64 followed in 1983.

In 1983, Kevin Hunt ported Lunar Leeper to the Atari 400/800 line of 8-bit computers. The Atari version was released with the same cover art and box as the Apple II version and featured the name “Lunar Leepers” on the backside of the box, but not on the title screen.

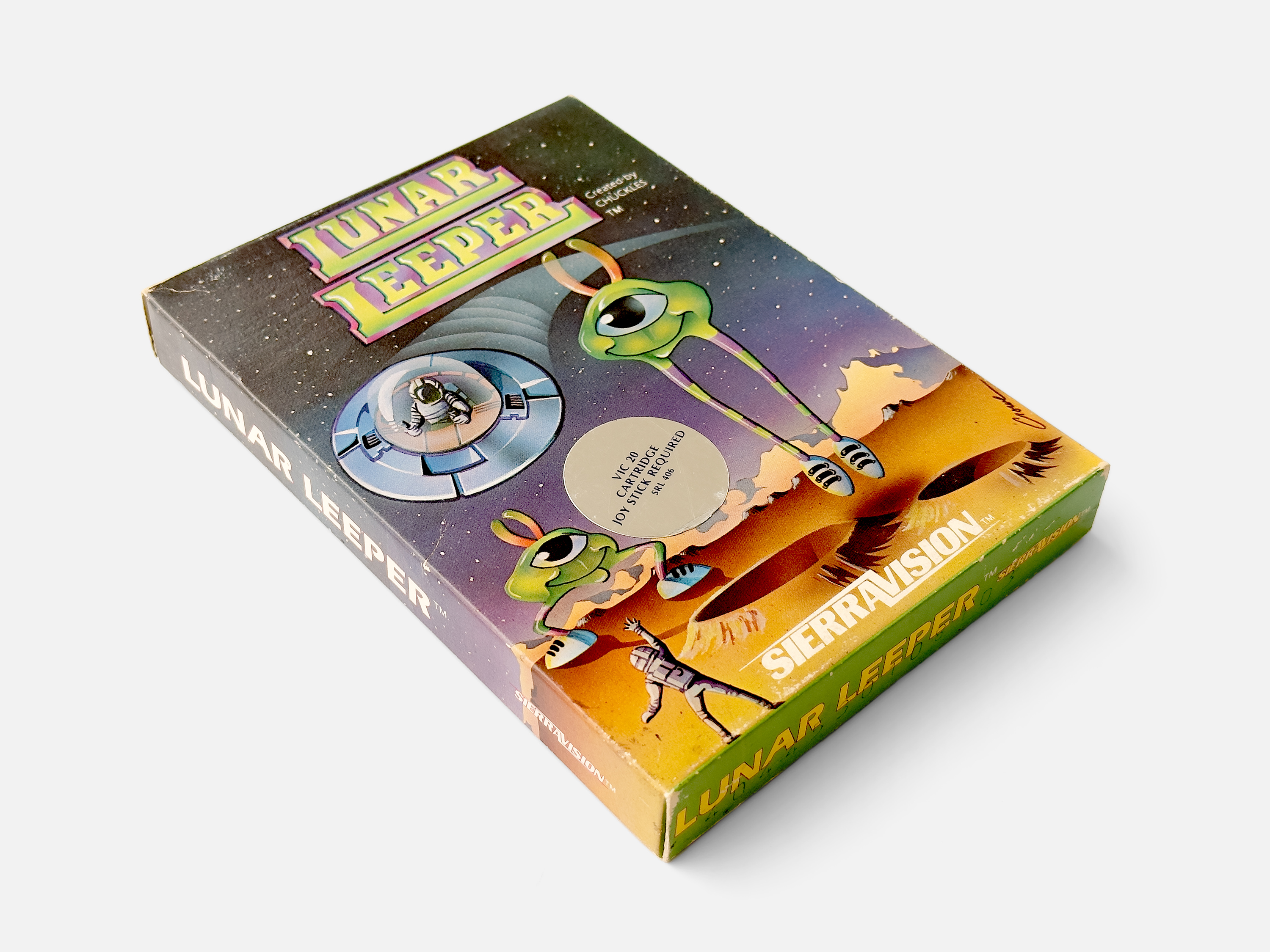

In 1983, Lunar Leeper was ported to the Commodore 64. The box featured new artwork by Mark Crowe, who had recently joined Sierra On-Line’s marketing department. Crowe would later become a game designer himself, creating the Space Quest series with Scott Murphy.

A Commodore VIC-20 version was also released in 1983. By then, the VIC-20 was far past its prime and obsolete in every aspect compared to Commodore’s newest offering, the C64, resulting in only a small number of copies sold.

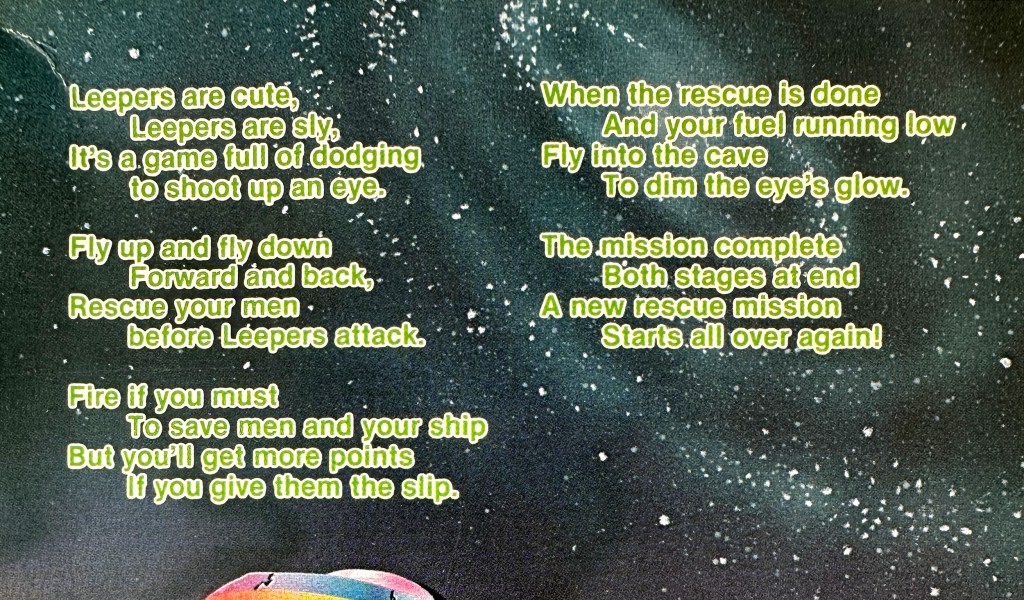

For the Commodore 64 and VIC-20 release, the gameplay was described in rhyme on the back of the box.

Upon its release, Lunar Leeper received generally positive reviews, particularly for its smooth animation and engaging gameplay. Critics praised its responsive controls and challenging level design, which required both reflexes and “strategic” thinking. The game’s visuals, especially its distinctive alien creatures, were noted as a standout feature for the time. However, some players found its difficulty curve steep, making survival a significant challenge. Despite this, Lunar Leeper developed a cult following among early home computer enthusiasts, and its mix of action and character helped distinguish it from other titles in the SierraVision lineup.

In Softline’s 1983 review, the game was called very addictive, with observers suggesting that players might easily lose hours to its loop of rescue and retreat. Personal Computer Games also reviewed it in its first issue with positive notes on its gameplay, and Ahoy! magazine described the VIC‑20 version as “original, ‘cute’, and hard as hell,” highlighting both its charm and its unforgiving difficulty.

During his time working with Sierra, Bueche ported Garriott’s Ultima II to the Atari 800, a substantial technical task in an era before standardized tools or emulators were available. He also ported Jawbreaker II and engineered hardware/software methods to transfer between systems.

The SierraVision label, for its part, was short-lived. It was intended to position the company in the rapidly expanding action and arcade-style segment, but the market was fiercely competitive, flooded with arcade conversions and clones that made differentiation difficult. Even with ambitious packaging and a lineup drawing on many popular themes, Sierra struggled to gain a foothold.

The challenges were compounded by the broader context of the early 1980s industry. After a surge in 1982 that had analysts predicting continual growth, the home computer and console markets plunged into a downturn by 1983. Sales collapsed, and unsold inventory piled up in warehouses. For Sierra On‑Line, abandoning SierraVision was as much a strategic choice as a response to market forces. The company’s strength lay in its critically acclaimed and commercially successful graphic adventures, games that would continue to define its identity.

Lunar Leeper’s titular alien later reappeared in Learning with Leeper, an educational game developed by Sierra as part of its brief foray into children’s edutainment software. The spin-off took a much different approach, using the friendly-looking Leeper character to engage young players in basic learning exercises, fitting well into the broader trend in the early 1980s where developers began exploring software beyond pure entertainment.

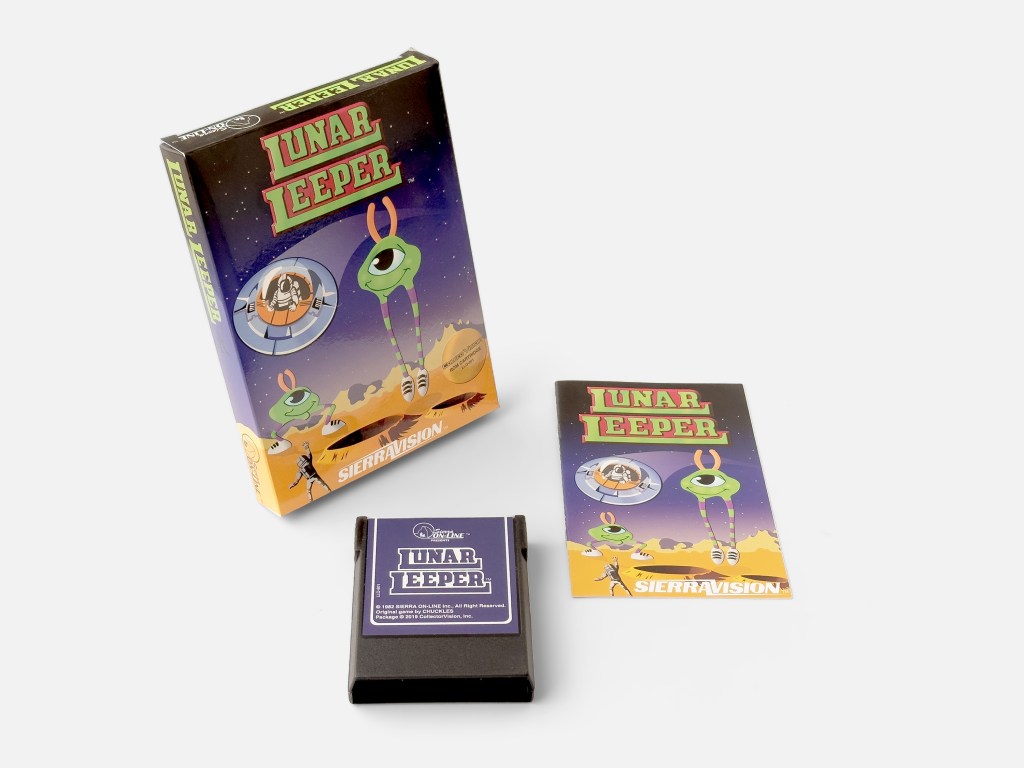

In 2019, a ColecoVision version was released by independent game developer and publisher, CollectorVision.

Within a year of Lunar Leeper’s release, Bueche’s career would take another turn, as he joined Richard, his brother Robert, and their father Owen Garriott to found Origin Systems in 1983. A company born of creative ambition and frustration with the limitations, especially those experienced working under an external publisher. Origin’s first offices were modest, literally assembled in a garage on family property, but the company quickly grew around the Ultima brand.

Bueche’s role at Origin expanded beyond porting early Ultima entries to other platforms. He designed and programmed original titles such as Caverns of Callisto, Autoduel, and 2400 A.D., and continued to support ports and programming on major series entries. Within the Ultima universe itself, Bueche’s legacy was memorialized in the recurring character of “Chuckles,” the court jester, a whimsical figure whose riddles and antics inserted a bit of cheerfulness into the series’ evolving universe.

As the 1980s progressed, Bueche continued to shape Origin’s output, but not without setbacks. 2500 A.D., a planned sequel to 2400 A.D., was abandoned in 1988 after disappointing sales. The same year, Bueche left Origin to complete a degree in electrical engineering at the University of Texas, graduating in 1990. Later, he moved into a series of senior technical and managerial roles across the software and entertainment industries.

An early employee photograph of Origin Systems.

Chuck Bueche is seated on the right, next to Robert Garriott, with Richard Garriott on the left.

Image from Softline magazine.

After his early successes in the home computer industry, Chuck Bueche continued to carve a distinctive path as a technologist and developer, under his company Craniac Entertainment, applying his talents far beyond traditional game design. Over the years, he worked on a remarkable range of projects spanning virtual reality, location-based entertainment, interactive attractions, and advanced graphics systems. From architecting free-roam VR platforms and immersive theme park experiences for Walt Disney Imagineering to developing gesture-based software using Kinect and pioneering real-time 3D visualizations, Bueche demonstrated a rare combination of technical mastery and creative problem-solving. He engaged with everything from cloud-based game software and autonomous boat navigation to embedded facial animation engines and high-performance graphics libraries, often taking a lead role in designing architecture, coding core systems, and managing small teams. Across decades, his work consistently pushed the limits of what interactive software could achieve, blending gameplay, simulation, and immersive environments with the precision of an engineer and the vision of a designer.

Sources: Wikipedia, Matt Barton’s Matt Chat Interviews with Chuck Bueche, ROM Magazine, Computer Magazine, aHoy!, Softline, Craniac Entertainment, LinkedIn…