The rapidly expanding home computer software market of the early 1980s was notoriously chaotic, crowded with tiny publishers that appeared and vanished within the blink of an eye. Ronald Unrath, a practical‑minded entrepreneur from Lake Zurich, Illinois, viewed that same volatility as an opening, a chance to build a disciplined, reliable business in a space defined by instability. He wasn’t a programmer or a grand visionary with a burning creative mission. He simply saw a retail economy on the rise, one with potential waiting to be tapped and organized. His plan was to find dependable local programmers, produce approachable software with clean packaging, deliver it on time, and, if possible, earn the trust of customers. While Unrath may have seen the broader software market as full of opportunities, it was adventure games, with their broad appeal and eager audience, that ultimately came to define his new venture.

In 1981, from his home, Unrath founded Phoenix Software. He lacked a national distribution network, brand recognition, or a stable of known designers, but he did find committed programmers, among them Paul Berker, whose early adventure games helped shape the company’s direction. At this point, the Apple II adventure market was both thriving and turbulent. Adventure International and On‑Line Systems, soon to be Sierra On‑Line, had already carved out the commercial space, one with its text‑only adventures, the other with pioneering illustrations. Infocom was beginning its rise, its polished storytelling already pushing expectations ever higher. New adventure games arrived so quickly that players often struggled to distinguish accessible, friendly titles from those that would leave them hopelessly stranded. Still, the hunger for these magical worlds was undeniable. It was a market with momentum and, despite the competition, room for contenders willing to find their place in the crowd.

Berker’s text‑only titles, Birth of the Phoenix and Adventure in Time, were modest in scope and commercial success, yet carefully constructed. They introduced a customer‑friendly “class” rating system from Class 1 to Class 5, helping newcomers avoid venturing into challenges far beyond their comfort zone.

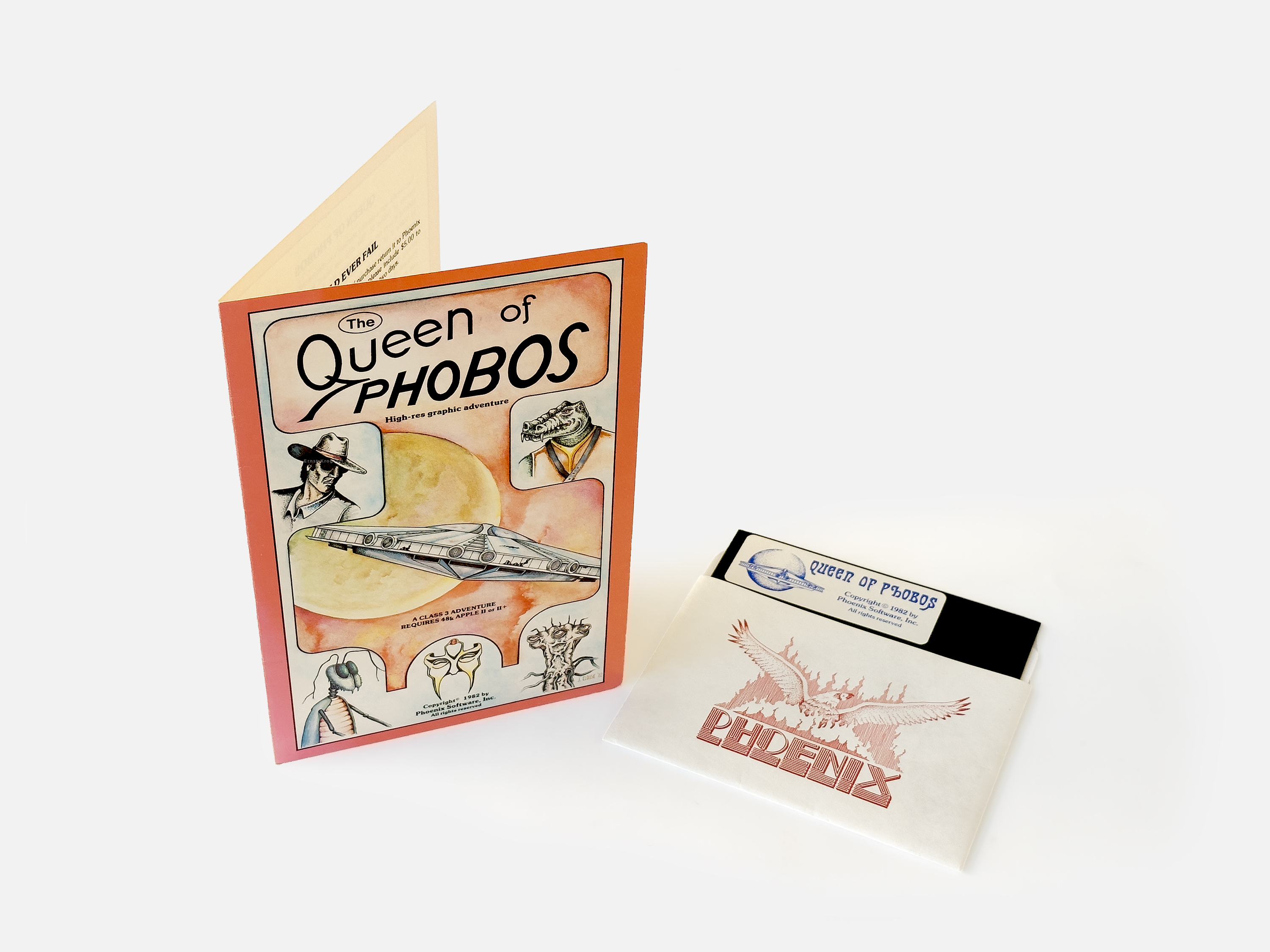

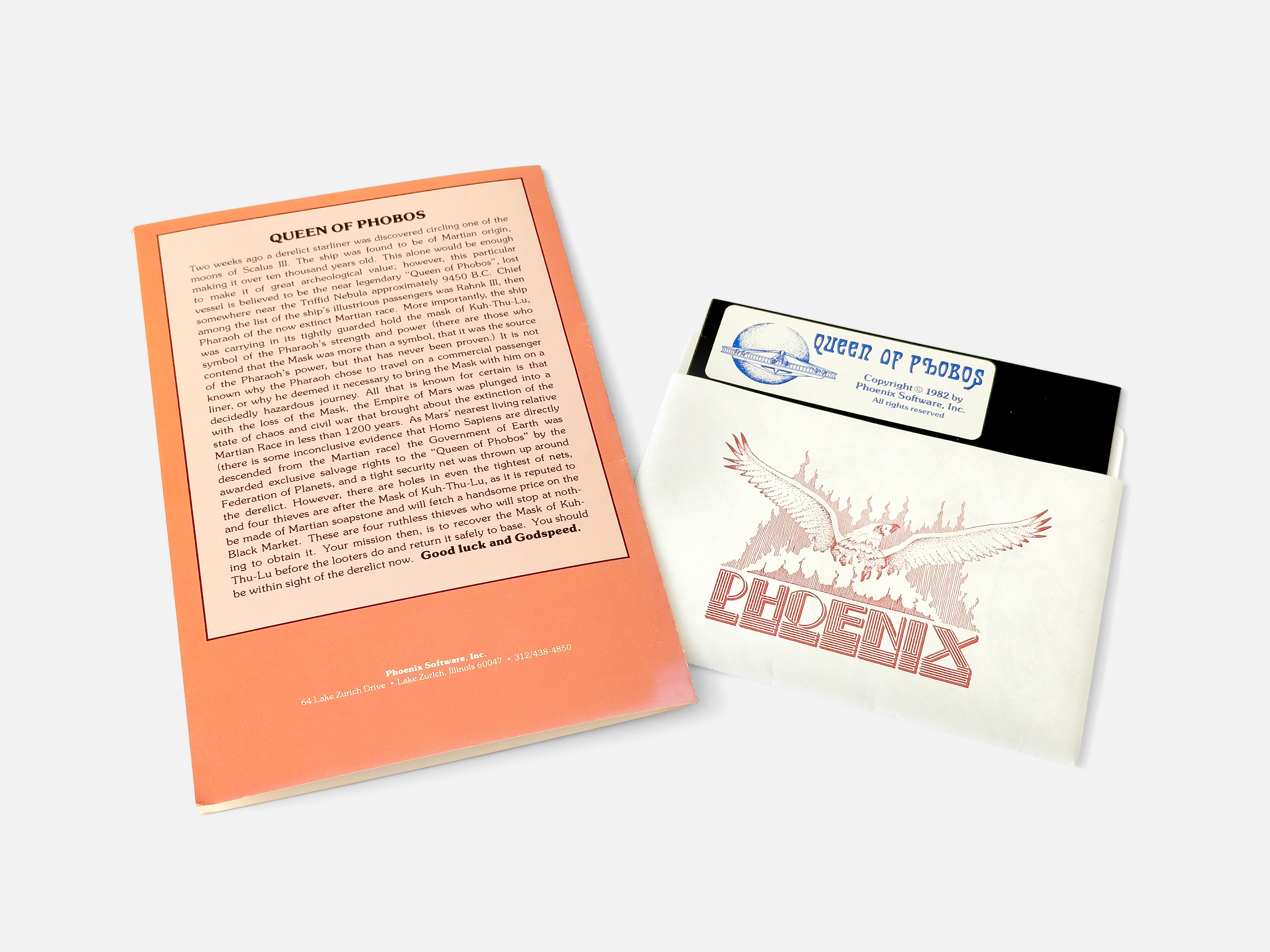

Phoenix’s early momentum was interrupted abruptly in 1982 with its third adventure game, The Queen of Phobos. The packaging described the game as a “High‑Res graphic adventure,” a phrase Phoenix believed to be a simple, literal reference to the Apple II’s graphics mode. Sierra On‑Line saw it differently. Having branded its own early adventure line as the “Hi‑Res Adventure” series, Sierra considered the wording a proprietary mark and moved swiftly. In October 1982, a federal court issued a temporary restraining order barring Phoenix from using the phrase. A preliminary injunction followed in February 1983, the judge finding that Sierra was likely to prevail if the case continued. For a small publisher, without the resources to wage protracted litigation or absorb the costs of retooling and reprinting packaging, the costs and distraction were serious. Phoenix was forced to halt shipments, recall packaging, and rethink its public identity at the very moment it was trying to grow.

Phoenix Software’s third adventure title, and the first to feature graphics, Queen of Phobos, released in 1982, used “High-Res graphic adventure” on the cover, a wording that put them into a legal dispute with Ken and Roberta Williams’ Sierra On-Line.

As the legal issue cast its shadow, the company’s most ambitious project to date, Sherwood Forest, was being crafted by programmer Dale Johnson and artist/technician Dav Holle. Together, they were shaping an illustrated adventure rooted in the Robin Hood legend. The tone would be lighthearted rather than solemn, comic rather than epic, and accessibility was the guiding principle. To give its illustrated efforts a recognizable identity, Phoenix introduced a new branding label, “Sof‑Toon Adventure.”

Johnson, a talented and dependable programmer, was precisely the kind of steady hand Unrath valued. He had a playful mind, and his earliest adventures, Mad Venture and Palace in Thunderland, created for another Illinois‑based publisher, Micro Lab, were small, text‑only creations built at a time when the genre was still finding its footing. In contrast to the often unforgiving nature of early ’80s adventure design, where many titles were laced with dead ends, obscure puzzles, or arbitrary parser tricks that punished all but the most stubborn players, Johnson’s puzzles leaned toward wordplay and lateral thinking rather than cruelty. While his games imposed tight timers and pressure mechanics that could feel harsh and even brutal, their difficulty came from deliberate design rather than sloppiness.

Holle, whose earliest contributions to Phoenix had been technical, copy‑protection routines, support work, the kind of invisible engineering that rarely earned attention, possessed a quality that was rare in an era still dominated by programmer‑art. He had a distinctive, confident visual style. Holle’s illustrations had a lively, cartoonish energy, using Apple II high‑resolution tricks and inventive dithering to produce images richer and more charming than the hardware seemed capable of. Where many early adventures simply labeled rooms with text and child-like drawings, Holle’s images hinted at personality and artistry.

Before Sherwood Forest took its final shape, Holle was already making his mark in the Apple II world with Zoom Grafix, a high‑resolution graphics printing package released through Phoenix Software. The package let Apple II owners work with hi‑res screens and a wide range of printers in ways the built‑in routines could not. With support for multiple printers and interface combinations and a clever “Zoom Window” for selecting portions of the screen, it was a utility aimed at enhancing how graphics were produced and printed at a time when creative output tools were still scarce. Where Penguin Software’s The Graphics Magician succeeded through widespread adoption and licensing, becoming, for a period, a de facto standard for adventure game visuals and animation across many publishers, Zoom Grafix never achieved the same widespread success, but it did become Phoenix Software’s best-selling title.

Johnson designed a straightforward adventure that encouraged players to help Robin Hood outwit the Sheriff of Nottingham and ultimately win the favor of Maid Marion. The puzzles were gentler than many games of the era, the writing conversational, the structure compact. Phoenix designated the game Class 3, “average difficulty,” signaling that this was intended neither as a punishing gauntlet nor as a beginner’s tutorial. It was simply meant to be accessible and enjoyable.

Holle’s artwork and simple animations lifted the Apple II’s limited capabilities into something bright and inviting, resulting in one of, if not the best-looking, adventure titles when released. Characters were expressive, and backgrounds were detailed and cheerful. Where The Queen of Phobos had used graphics sparingly with simple black‑and‑white line drawings, Sherwood Forest embraced visuals fully,

Sherwood Forest was mentioned as early as 1981, in a letter from Unrath to dealers. Later, in a Phoenix Software dealer price list dated May 27, 1982, it was noted that it would be available in September of the same year.

Sherwood Forest, Phoenix Software’s most ambitious title to date, was released for the Apple II in the Autumn of 1982.

It would be the first, and ultimately only, entry in the company’s planned line of adventures called “Sof-Toon Adventure”.

Sherwood Forest, while borrowing names and elements from the classic Robin Hood legend, takes a playful, comic approach to the story. Players guide Robin Hood while pursuing the heart of Maid Marion. The game’s gentle puzzles, conversational text, and colorful Apple II graphics create an approachable adventure that balances humor, charm, and challenge.

When Phoenix released the game in the autumn of 1982, hopes within the small company were cautiously optimistic. The legal issues with Sierra hung over its branding efforts, making national distribution difficult, and Phoenix was too small to wage an advertising campaign worthy of larger publishers. Yet word of mouth spread, and Sherwood Forest quietly became one of Phoenix’s better‑selling titles, eventually reaching an estimated 1,500 copies sold. A figure modest by national standards, but meaningful for a suburban publisher with no major retail presence. Its appeal lay in its charm as it wasn’t trying to be a grand epic, but rather the sort of game that parents could give to children, that new Apple II owners could finish, and that seasoned players could appreciate.

Reviews were relatively few but telling, and they leaned toward appreciation for what the game was, not what it wasn’t. One of the most cited contemporary assessments came from Computer Gaming World, where reviewer John Besnard summed up the game simply but pointedly: “Phoenix has put everything in place to allow them to create a really great adventure game. Sherwood Forest isn’t bad, it’s just too short.”

More expansive praise appeared in Softline magazine, where the game’s visuals, craftsmanship, and tone drew particular notice. The reviewer called the graphics “wonderful,” highlighting the good‑natured cartoons by Holle and the expressive personalities of characters such as the shifty tax collector and the merry band of outlaws. The technical execution, the piece noted, was crisp, screen redraws were fast, text commands responded cleanly, and save/restore worked smoothly. Unlike many adventures of the time, where random deaths and obscure lore could thwart progress, Softline emphasized that Sherwood Forest’s puzzles were tough but fair, and that there were enough clues for clever players to make steady progress. It was witty and consistent, offering gentle hints and even playful reprimands along the way.

The appreciation for fair design was echoed in The Book of Adventure Games from 1984, which included Sherwood Forest among its catalog of notable interactive fiction. There, the title was described as “extremely well implemented,” with clever puzzles, a responsive parser, and a tone that made it appealing for beginning and intermediate players alike, even if it lacked the sprawling depth of some of its competitors.

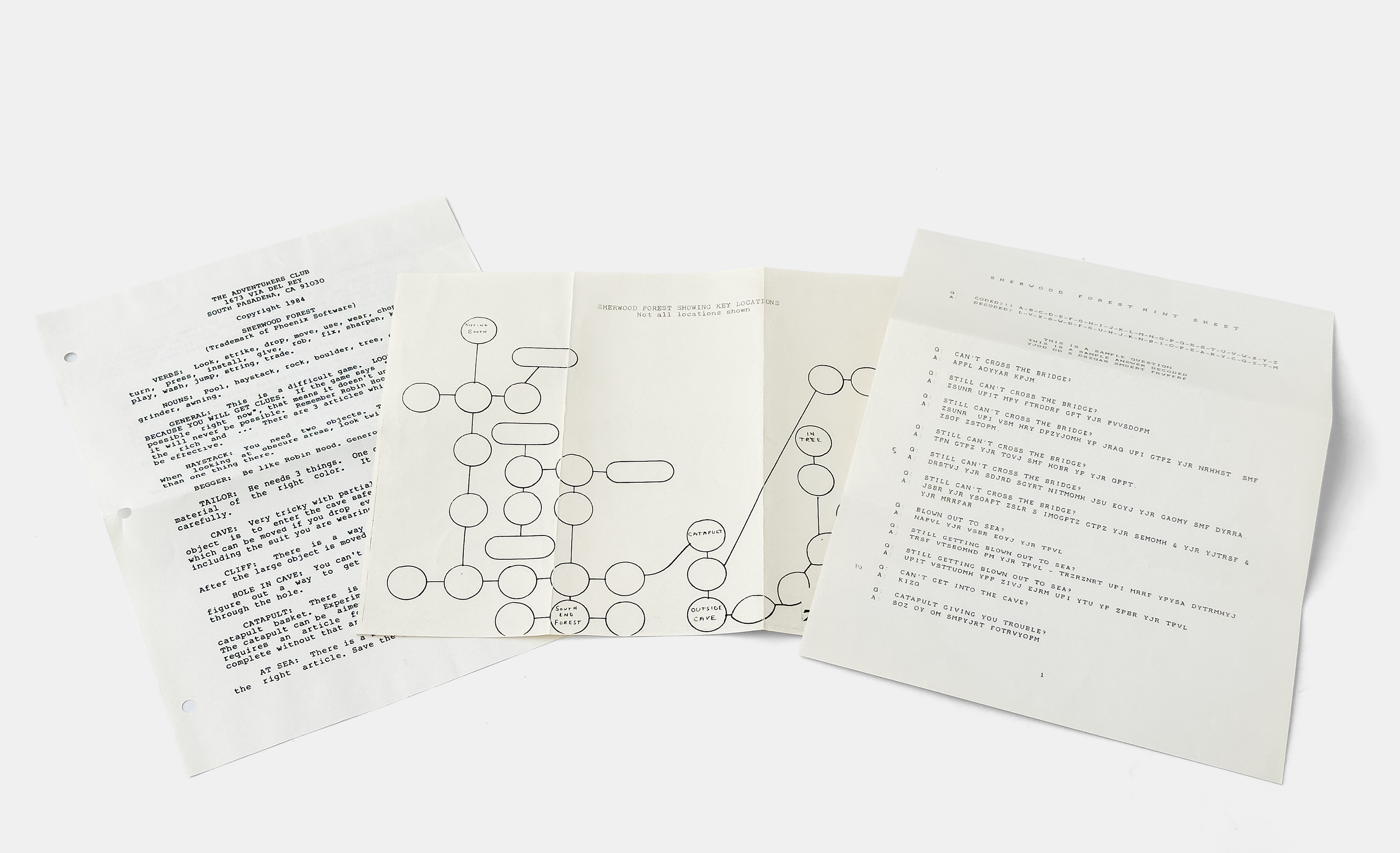

In an era before the World Wide Web and online hints, small enthusiastic user groups dedicated themselves to providing guidance for early 1980s adventure games. Shown here is a 1984 walkthrough by California-based The Adventures Club, alongside an official map and hint sheet that could be ordered directly from Phoenix Software.

Phoenix Software authors Dav Holle and Dale Johnson, with Holle seated at the Apple II keyboard and Johnson standing just behind him. The photograph was taken at Data Domain in Schaumburg, Illinois, less than half an hour’s drive from Phoenix Software’s base, around the time of Sherwood Forest’s release. Data Domain was a local computer store active throughout the late 1970s and early 1980s, working closely with area programmers and small publishers. Specializing in computers, software, magazines, and technical books, it served as a neighborhood hub for Chicago-area enthusiasts. For a company like Phoenix Software, lacking national distribution and often overlooked by major wholesalers, stores like Data Domain were essential, providing a direct path for its games to reach customers.

Image from Gallery of Undiscovered Entities (gue.cgwmuseum.org)

Phoenix Software could not escape the long‑term consequences of its legal and distribution struggles. By 1984, the company was sold, rebranded as Zooom Software, and later reorganized as American Eagle Software. The transitions gave the company a few additional years of activity, but never restored its earlier momentum in the game industry. As larger publishers consolidated their power and shelf space became scarce, the market grew less forgiving of smaller companies like Phoenix.

The people behind Sherwood Forest and Phoenix Software scattered into different paths as the industry matured. Unrath moved on to other ventures outside of games. Berker, whose early work had helped shape Phoenix’s identity, shifted into business programming. Holle, whose artwork gave the game its soul, went on to serve at Origin Systems as lead programmer and team manager working on the Commodore 64 and IBM PC remake of Ultima I. Johnson, except for two titles released in 1983 and 1985, respectively, left behind little further trace in the commercial games industry.

Sources: Gallery of Undiscovered Entities, Micro 6502 Journal, Wikipedia, Creative Computing, Kilobaud, BYTE, Computer Gaming World, The Book of Adventure Games…