In the early-to-mid 1970s, long before personal computers found their way into bedrooms and basements, Jeff McCord, a teenager in Lexington, Kentucky, was imagining worlds of shadowed corridors, lurking dangers, and treasures just out of reach. Fueled by the rising Dungeons & Dragons craze sweeping the country, his visions slowly took shape, visions that, almost ten years later, would evolve into a commercial reality.

McCord’s father, a computer science professor at the University of Kentucky, recognized his son’s interest and granted him a student account on the university’s mainframe. A hulking Digital Equipment Corporation PDP system, a room-filling colossus whose blinking lights and endless rows of switches seemed to guard secrets only the fortunate, or audacious, could ever uncover. Late into the night, McCord explored early dungeon crawlers and text-based adventures, including Will Crowther’s legendary Adventure. He memorized every room, every hidden passage, every hazard, all the while imagining how he might one day build something like this of his own.

Back at his high school, the computer lab’s Commodore PET was a precious resource, a compact but surprisingly capable machine with an integrated monitor, keyboard, and cassette storage that made it a self-contained workstation. While its 4Kb of memory and 1 MHz MOS Technology 6502 processor were a far cry from the mainframe McCord had grown accustomed to, it was perfect for experimentation.

The lab’s teacher, Mr. Syler, was famously strict. “No games in the computer room,” he would bark, though he couldn’t help notice McCord’s flair and curiosity. Quietly, he loaned Jeff a key to the lab, allowing him to experiment after hours. Here, he began building the foundations of what would eventually become Sword of Fargoal, his take on the creations that had captured his imagination. He created tables for monsters, treasure probabilities, traps, atmosphere, and tension. His early designs were as much experiments in psychology as in programming, exploring how uncertainty and surprise could grip a player as effectively as any text or graphics.

The overall design philosophy came from the mainframe dungeon crawlers he had explored. Games like dnd and Oubliette introduced procedural dungeons, permadeath, and unpredictable challenges. Unix’s early Rogue iterations offered similar lessons, with a dungeon that changed with each playthrough, a reward structure emphasizing skill and adaptability over memorization. McCord internalized the ideas, sketching worlds on paper. He essentially wanted to craft a dungeon that reshaped itself each time the player entered, and centered the experience around a simple, pressure-filled objective. Descend, recover, escape.

By 1981, the home computer revolution was well underway, and the Commodore VIC-20 became 18-year-old McCord’s gateway to the broader world of computing. With just 5 KB of static base memory, small even by 1981 standards, the same processor as the PET, and a crude character set, the machine was limited, but for McCord, raw specifications didn’t translate into what made a good experience. Working in Commodore BASIC, he wrote and rewrote map generators, optimized combat routines, and eventually devised a system capable of generating an entire dungeon floor on the “fly”. Atmosphere and suspense were paramount. “Flickering” torches, low visibility, and the uncertainty of each staircase conveyed danger.

McCord’s hobby project merged into a polished demo. The high-school PET and now VIC-20 experiment, eventually dubbed GammaQuest, was ready to be shown to publishers. Among those who responded, California-based Epyx stood out. The company had already achieved commercial success with the 1979 title, Temple of Apshai, a dungeon-crawling RPG that sold exceptionally well but relied on static, predesigned rooms rather than procedural generation.

At the time, Epyx was transitioning from its earlier identity as Automated Simulations, moving away from heavy rule-based games toward a portfolio more accessible to mainstream players. McCord’s procedurally generated dungeons and high-stakes but very accessible gameplay offered something new, a sense of danger and unpredictability that could keep players of all calibers coming back for endless variations.

The original title, Sword of Fargaol, Fargaol being a nod to the archaic spelling of “jail,” was, at Epyx’s suggestion, simplified to the more approachable Fargoal. Beyond the name, the publisher played a role in shaping parts of the game, offering playtesting feedback, design suggestions, and guidance to help McCord refine the final product.

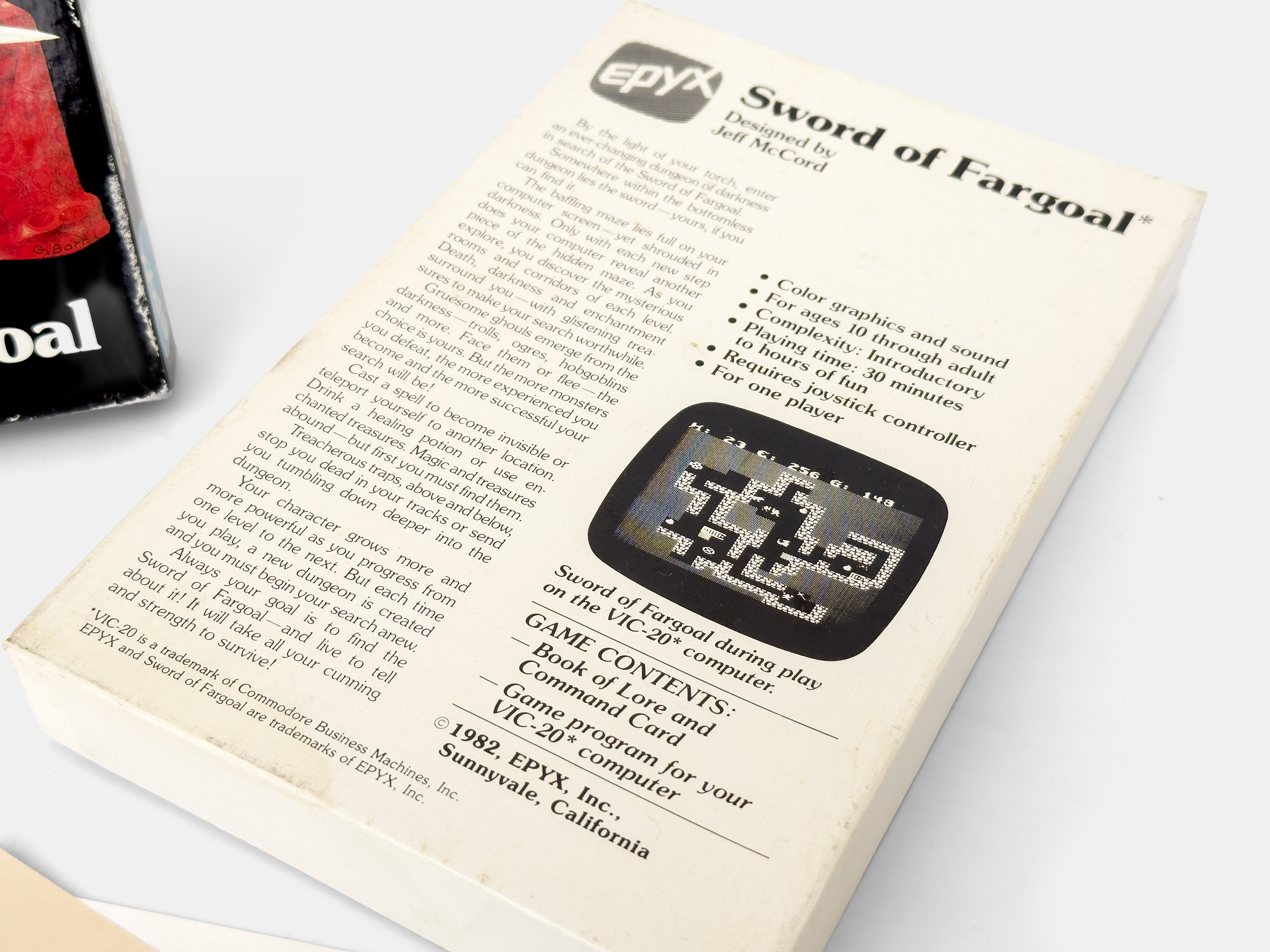

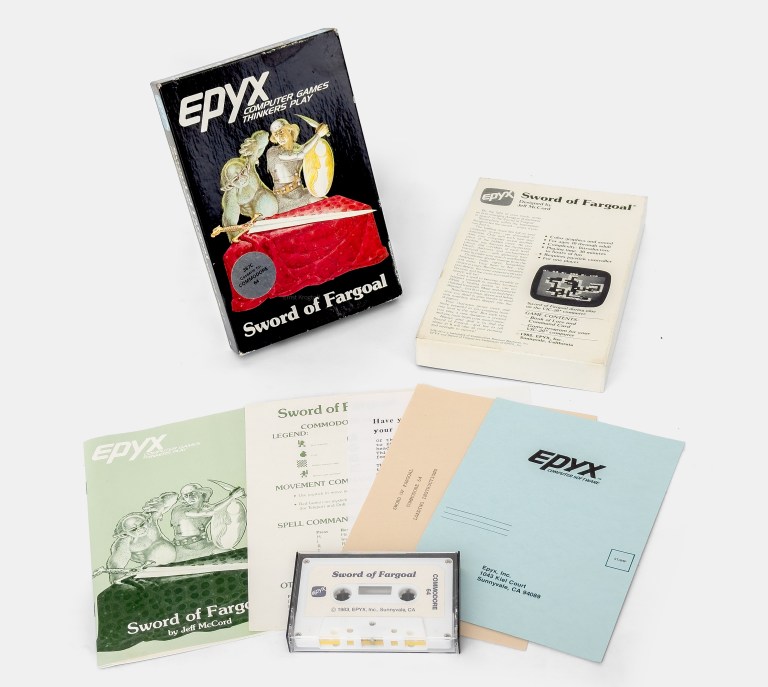

With Epyx’s contributions, McCord’s teenage after-hours experiments became a commercial reality when his Rogue-like procedural dungeon crawler, Sword of Fargoal, hit shelves in 1982.

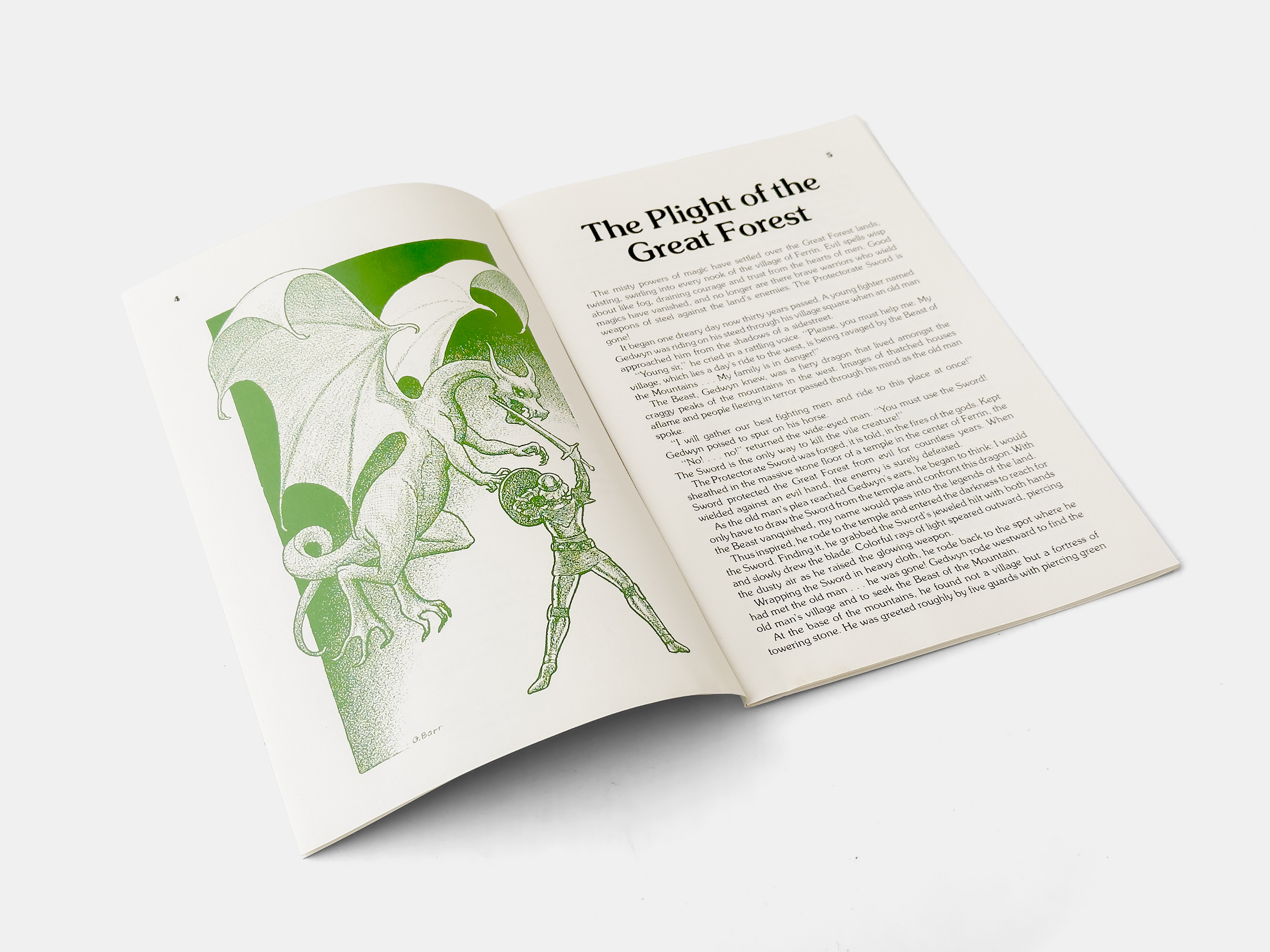

The Protectorate Sword, forged to defeat evil, has been stolen by the wizard Ulma and hidden deep within a sprawling underground labyrinth. Only by recovering it and returning it to Gedwyn, the blinded hero, can Ulma be destroyed forever. Players descend into ever-shifting, procedurally generated dungeons, searching the treacherous depths of levels 15–20 for the legendary Sword of Fargoal. Once found, a relentless 2,000-second (33 minutes) countdown begins, forcing a frantic ascent back to the surface before the dungeon collapses. If monsters attack, they will likely steal the sword and bring it back to the level where it was found, making luck, timing, and strategy essential. Even decades later, McCord admitted he had survived the dungeon only twice in thirty years.

While the game demanded a 16 KB memory expander to run, the accessory had become so common that it hardly deterred players.

The following year, with the now hugely popular Commodore 64 offering expanded memory and richer graphics, rendering the VIC-20 and its ecosystem obsolete overnight, Epyx commissioned a port of Sword of Fargoal. McCord remained the creative lead, overseeing the project while friends Scott Carter and Steve Lepisto contributed assembly routines to speed up draw routines and dungeon generation. Though the hardware had changed, the dungeon’s pulse remained identical. Procedural generation, random encounters, traps, and the unyielding 2,000-second clock from the moment the sword was found ensured that decisions carried weight.

Following the VIC-20 debut, Epyx released the Commodore 64 port of Sword of Fargoal in 1983. Jeff McCord remained the creative lead, while Scott Carter and Steve Lepisto handled the assembly-level routines that sped up graphics and movement. The game shipped on either cassette or 5¼″ floppy disk and was updated with slightly better graphics, a few added features, and ominous sounds punctuated by monster movement.

The 1983 Commodore 64 version expands on the VIC-20 original with slightly richer graphics and faster draw routines, yet the core experience remains unchanged.

Fargoal’s design was revolutionary precisely in its subtlety. Whereas many early 1980s dungeon crawlers emphasized fantasy spectacle, complex mechanics and stats, or character focus, McCord focused on simplicity, the fear of the unknown, the thrill of exploration, and the rising dread as time slipped away. A fog-of-war concealed unexplored corridors, monsters moved unpredictably, heard before seen, and treasures tempted with the ever-present risk of death, yet the rules were often much fairer and more consistent than the competition.

The manual (Book of Lore) tells the mythic back-story of the Protectorate Sword, player characteristics, monsters, treasure-and-trap mechanics, and an introduction to the procedural dungeon levels and, of course, the game’s iconic 2,000-second escape timer.

Illustrations and cover art were done by well-known American fantasy/sci-fi illustrator George Barr, whose work graced many science-fiction and fantasy volumes of the era.

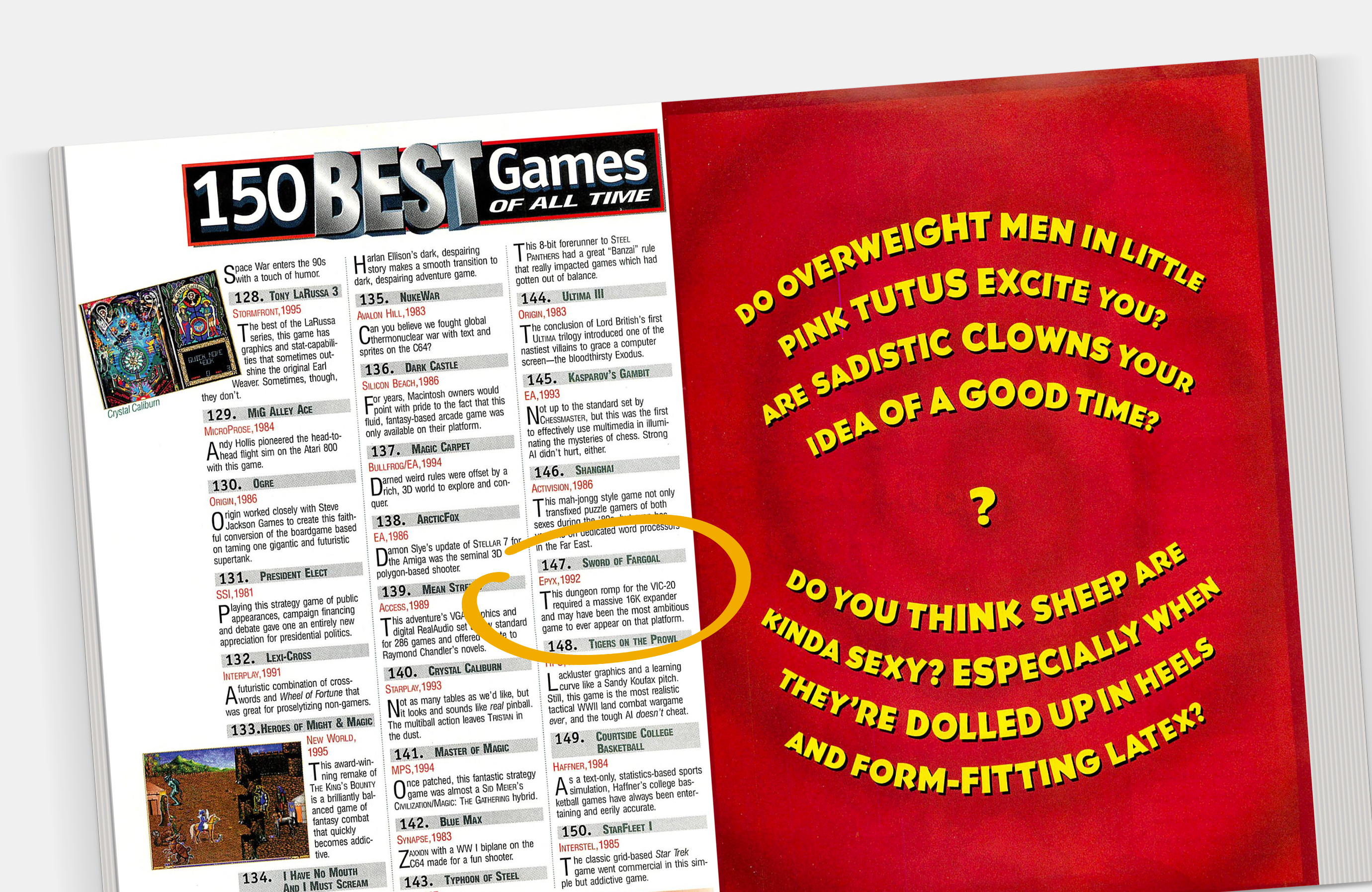

Reception was quietly enthusiastic. Critics praised its addictive design, tense atmosphere, and procedural depth, drawing comparisons to Rogue and Temple of Apshai, though neither fully captured McCord’s elegant balance of accessibility and suspense. He earned modest royalties, reportedly around $40,000, yet the game’s influence stretched far beyond its official sales thanks to rampant pirating. Commodore enthusiasts treasured it, sharing copies through user groups and BBSes, and the game would go on to achieve a lasting cult status. Years later, the game’s influence was acknowledged when Computer Gaming World in November 1996, placed Sword of Fargoal at #147 in its “150 Best Games of All Time.”

In November 1996, Computer Gaming World, Issue 148, ranked Sword of Fargoal #147 in its “150 Best Games of All Time.”

The magazine mistakenly listed it as a 1992 (a small oversight) release, but correctly noted its significance as one of the most ambitious titles for the Commodore VIC-20.

The 2000s brought a resurgence of interest in retro computing, and McCord returned to the spotlight. Collaborating with Paul Pridham and Elias Pschernig, he helped develop a modernized remake, which brought the procedural heart of the game to modern platforms while retaining the tension and challenge of the original. Reflecting on the enduring appeal, McCord emphasized his philosophy: Players were never meant to be all-powerful; they had to struggle, improvise, and rely on their wits. The game was never about dominance; it was about suspense, survival, and the stories players carried from the depths of the dungeon.

Following Fargoal, McCord continued to explore game development, though none of his subsequent projects achieved the same lasting visibility. He experimented with new mechanics, designs, and platforms, including a proposed project called Tesseract Strategy, which attracted attention from publishers like Electronic Arts, who even flew him to San Francisco for promotional work. Though the project never materialized, McCord’s work on Fargoal cemented his place in the early home-computer games. After leaving California in the mid-1980s, he studied filmmaking, then moved into graphic arts and freelance design, becoming a layout/production artist in New York for The Village Voice and National Lampoon. Over time, his career also expanded into prepress and Photoshop work, house restoration, and even board- and card-game design.

Sources: Matt Barton’s book: Dungeons & Desktops, Wikipedia, Wired, Reddit, GameBanshee, TouchArcade, Kickstarter, Computer Gaming World, fargoal.com…