On June 6, 1982, Lucasfilm took a leap into interactive storytelling, partnering with Atari to bring a new generation of video games to life, without capitalizing on its hugely popular Star Wars or Indiana Jones franchises.

When George Lucas founded his production company, Lucasfilm, in 1971, he did so with a vision of merging technology and storytelling to push the boundaries of cinema. By the early 1980s, he had changed cinema in ways few could have imagined. His Star Wars space saga had become a cultural phenomenon, and The Empire Strikes Back made clear it was no stroke of luck. Lucas had built a technological ecosystem, ranging from visual effects at Industrial Light & Magic to sound and editing at Skywalker Ranch. Despite the immense success, he recognized that technology wasn’t just a tool for the silver screen but a playground for storytelling and expression. In his view, “the goal was to find new ways to tell stories,” and the video-game industry, still early and rough around the edges, offered an interactive medium, wide-open and undefined.

In 1979, Lucas had begun assembling a Computer Division within Lucasfilm, a forward-looking research lab exploring graphics, sound, editing, and interactivity. The division came to house three specialized groups: the Graphics Group (which would later become Pixar when sold to Steve Jobs in 1986), the Audio Group (which developed the SoundDroid system), and a smaller Games Group, established in 1982, whose task was to explore how computers could create experiences rather than merely process data. It was not a commercial venture, at first, but an experiment in digital entertainment and storytelling.

Lucas let the team operate relatively autonomously, focusing on raw talent and experimentation rather than micromanagement and tight deadlines. Internally, simply known as the Games Group, but as prototypes grew into playable experiences, the group adopted a more public identity. The name Lucasfilm Games started appearing in 1984, first on internal Atari materials and trade-show previews. By the time the studio’s first titles reached the public the following year, it had become the official banner, one that suggested a new kind of creative bridge between Hollywood and Silicon Valley.

To lead the new venture, Ed Catmull, head of the Computer Division, appointed Peter Langston, a musician and programmer from the Unix world who described himself as a “playful thinker.” Langston came with his own experimental streaks, having created games and software, and was quite more comfortable with algorithms than boardrooms. He accepted the job on the condition that he could hire tinkerers, people who saw games as art, and not mere commercial products. In an interview in 1984, he said, “I started hiring people who struck me as individuals who would go beyond what’s already been done and who would have interesting, new ideas.”

Among Langston’s first recruits was David Fox, an educator turned interactive-media designer and programmer who, in 1977, together with his wife Anne, had co-founded Marin Computer Center, the world’s first public-access microcomputer center. He was joined by David Levine, a forward-thinking systems programmer with a strong grasp of hardware and graphics. Noah Falstein, whose background in both computer science and psychology gave him a keen interest in how players think and respond to challenges. Gary Winnick, a self-taught artist, brought visual flair from his earlier role as the editor, artist, and writer for a comic magazine, while Charlie Kellner, a former Apple employee, contributed technical expertise from designing application and system software for the Apple II, III, and soon-to-be-released Macintosh.

Together, the eclectic group formed something resembling more of a research lab than a conventional game studio. Free from rigid schedules and commercial pressures, encouraged instead to prototype, experiment, and discard ideas until something truly magical emerged.

Original designers and programmers of the Lucasfilm Games Group. Pictured from left to right: Charlie Kellner (standing), David Levine (seated), Peter Langston, David Fox, Loren Carpenter (from the Graphics Group), and Gary Winnick next to an Atari 800 computer showing the golden Lucasfilm Games intro title.

Picture from Lucasfilm.com

The group’s financial foundation came from an unusual partnership with Atari. About a million dollars in seed funding in exchange for the right of first refusal on any games Lucasfilm produced (a contractual agreement that gave Atari the priority to buy assets before Lucas could sell them to someone else). The plan was for the Games Group to create titles for Atari’s 8-bit home computers and its Atari 5200 video console. For a while, everything went according to plan. The team built internal tools, experimented with technologies, and began work on several prototype games, using a 68000-based development system running the Unix operating system. But in 1983, the broader market collapsed. The North American video-game crash sent shockwaves through the industry, and by mid-1984, Warner Communications had sold Atari’s consumer division to Jack Tramiel. The deal with Lucasfilm disintegrated overnight. Planned releases of the group’s first two titles under the “Atari Lucasfilm Games” label were canceled, leaving the studio with completed projects but no publisher.

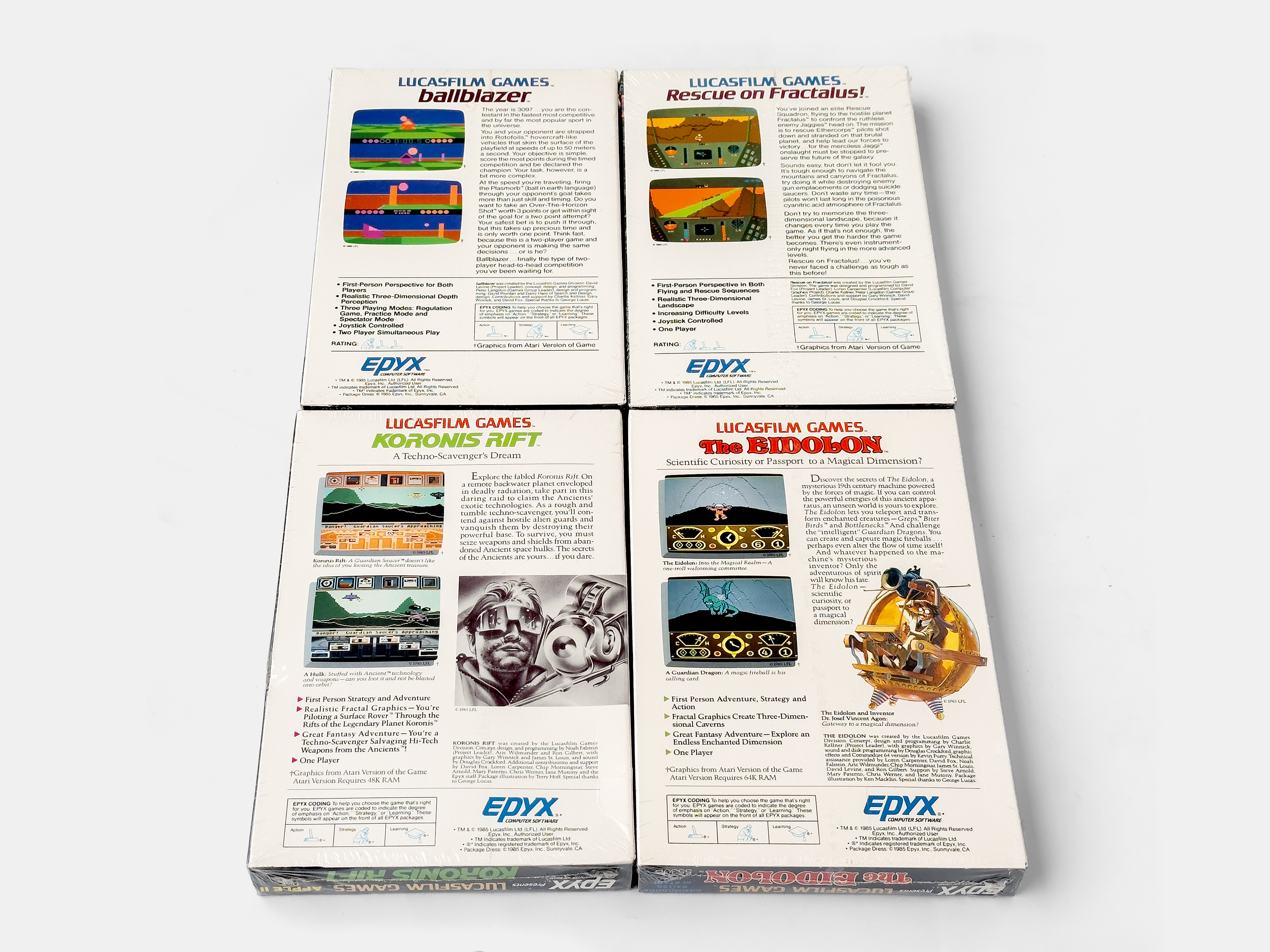

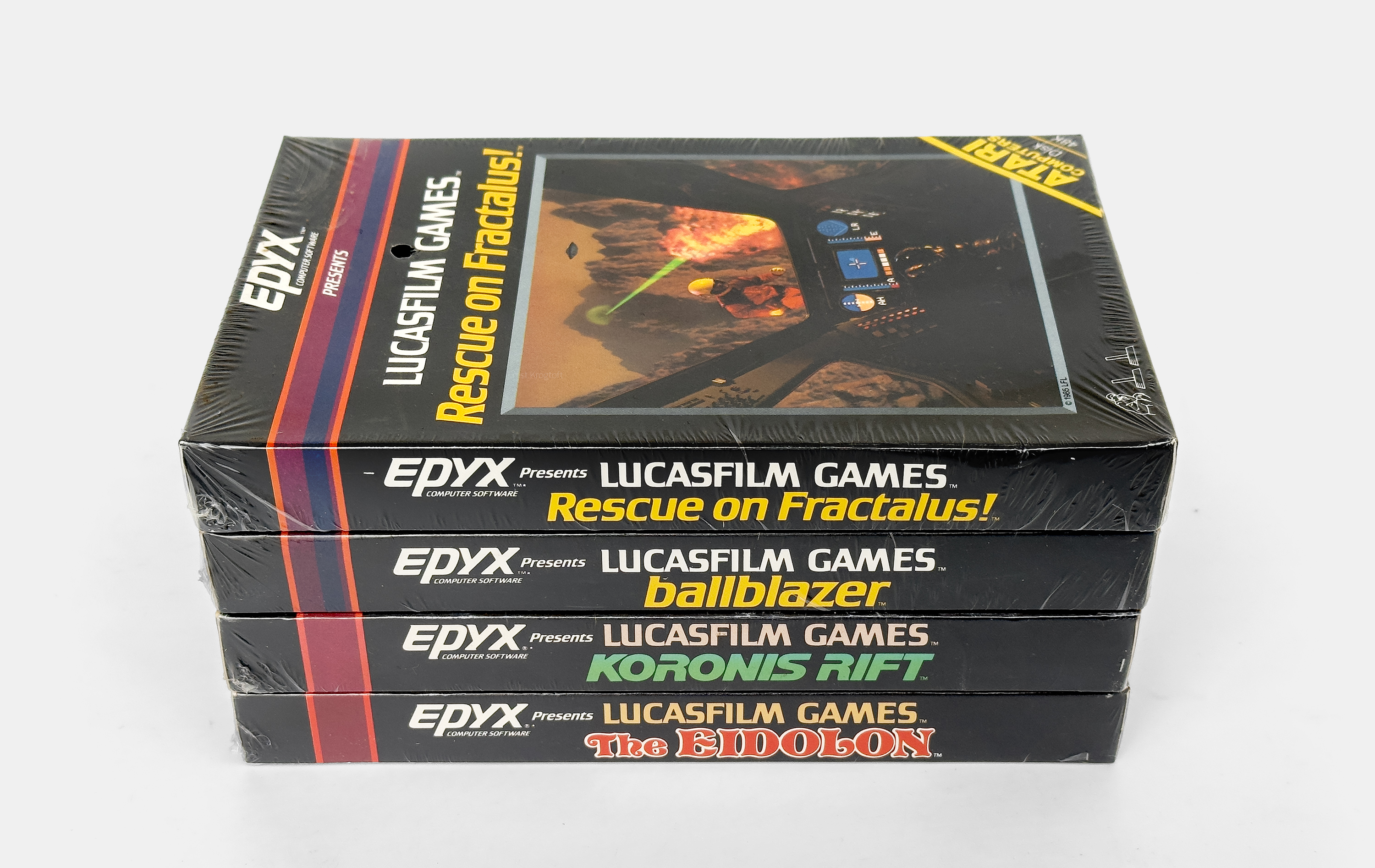

The group refused to let its work die, and in 1985, reached a new agreement with Epyx, a respected publisher known for its innovative sports and action titles. Under Epyx, Lucasfilm Games’ first titles finally managed to reach the public, each distinct, each pushing hardware and game design in new directions.

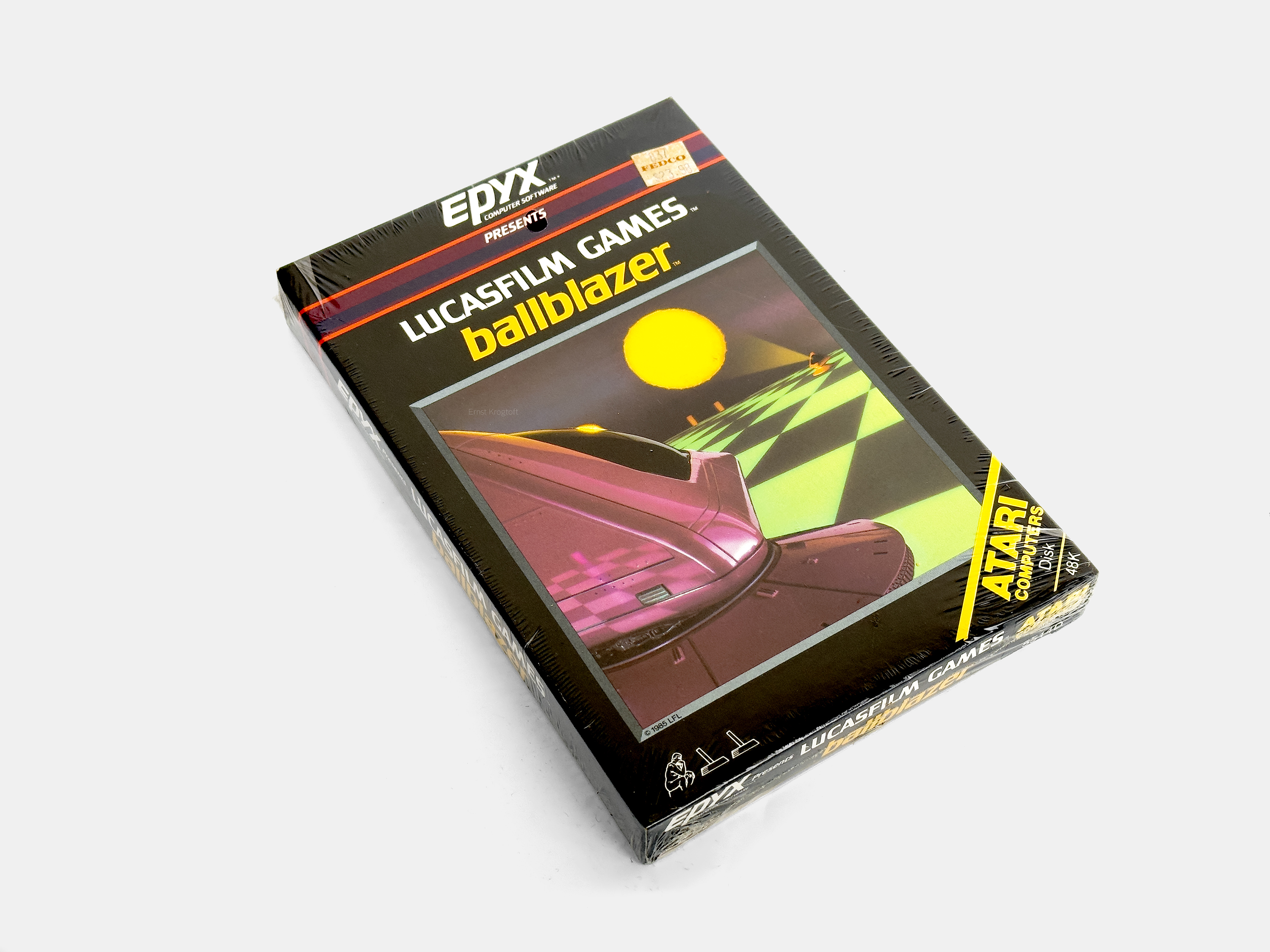

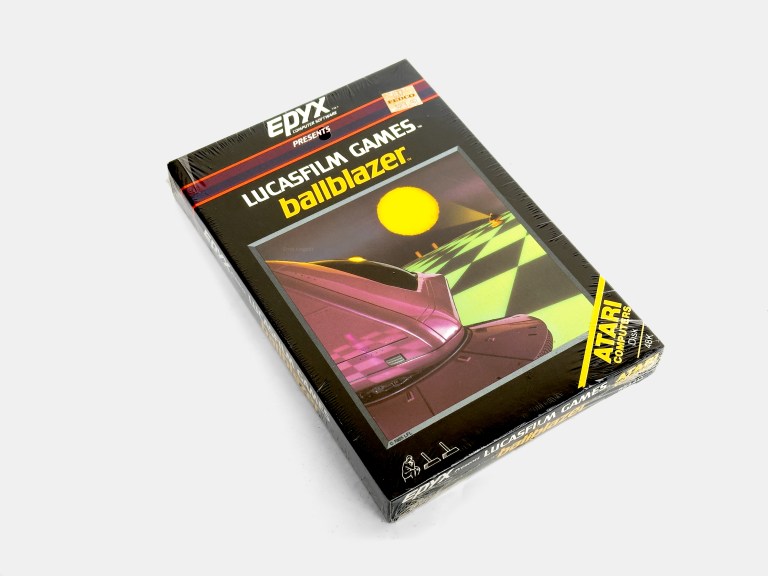

The first title, Ballblazer, emerged from Langston’s playful vision: What if sport from the future was abstract, symmetrical, kinetic, a zero‑gravity match between two hovercrafts? Levine led it, Fox and Winnick contributed design and visuals. On the Atari 8‑bit, the team squeezed smooth first‑person motion across a grid arena. The two‑player split‑screen allowed both participants to view their own craft’s perspective simultaneously. Algorithmic jazz‑fusion music composed by Langston ensured the soundtrack never looped in the same way twice. One reviewer later compared portions to Coltrane‑like improvisation. The game became an early proof that Lucasfilm Games could deliver an experience that felt fresh and cinematic.

The game even developed an unintended underground reputation before its release. A near-final beta had leaked onto pirate bulletin boards under the name Ballblaster, a title that, for a time, became more widely known than the official Ballblazer. Later, when a young Tim Schafer applied for a position at Lucasfilm Games, he mentioned to David Fox during an interview that he was a fan of Ballblaster. Fox gently corrected him, stating that Ballblaster was the pirated version. Despite the awkward start, Schafer was hired as a “scummlet,” an assistant designer and programmer. It was the beginning of a remarkable career within the company. Schafer would go on to co-create and write some of Lucas’ most iconic adventures, including The Secret of Monkey Island, Day of the Tentacle, and Full Throttle, titles that carried the same offbeat humor and human touch that became his hallmark.

Ballblazer was completed in the fall of 1983 under the Atari partnership. With the North American Video game crash and Atari’s consumer division being sold to Jack Tramiel in mid-1984, the planned release was left in limbo. The game eventually found its way to market in the spring of 1985 through a deal with Epyx, marking the public debut of Lucasfilm Games.

The game was ported to the Apple II and Commodore 64 in 1985, with versions for the Atari 5200/7800, Amstrad CPC, ZX Spectrum, MSX, and NES arriving the following years.

Two pilots face off in a futuristic one-on-one sport, maneuvering hovercrafts across a grid arena to blast a floating ball into their opponent’s goal—fast, fluid, and one of the earliest “3D” experiences on home computers.

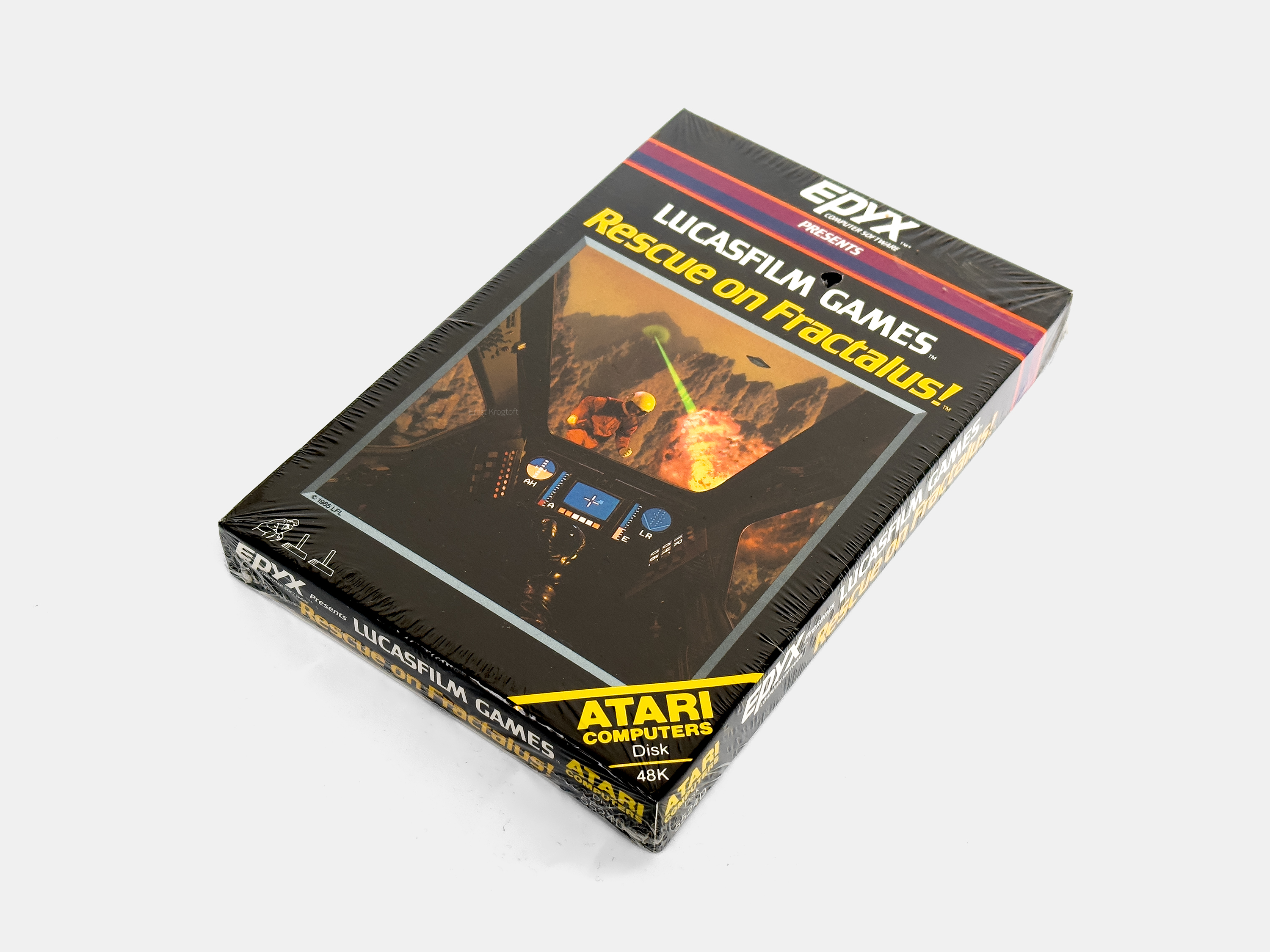

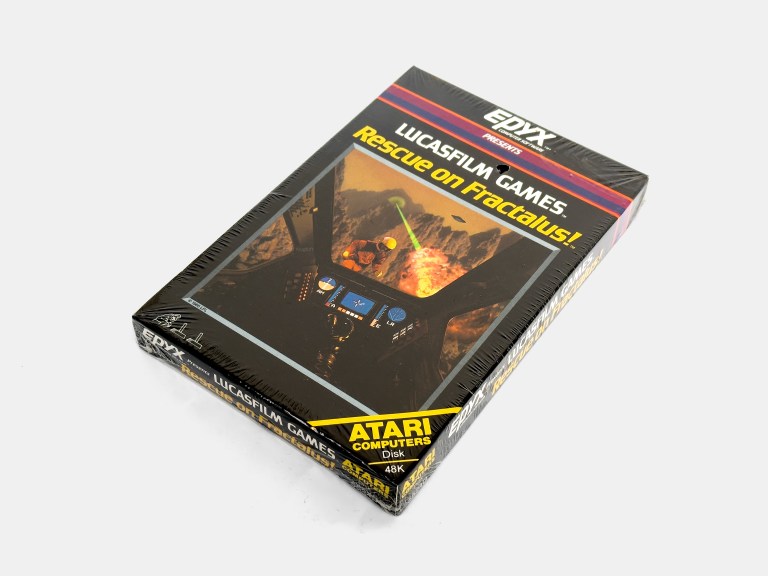

In parallel with Ballblazer came Rescue on Fractalus!. Fox drew inspiration from an offhand conversation with Lucasfilm’s graphics researcher and Industrial Light & Magic employee, Loren Carpenter, who was largely responsible for the fractal mountains in the Genesis sequence in Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan, the first completely computer-generated movie sequence, when it hit theaters in 1982. One day, Fox asked Carpenter if it was possible to generate fractal mountains on home computers. Carpenter left, borrowed an Atari 800, taught himself 6502 assembly, and understood how the system handled graphics. Weeks later, he returned with a functional fractal-mountain demo. Fox and Carpenter showcased it to Langston and the team. With fractal landscapes of peaks, valleys, and ridges, all rendered in “real time” at eight frames per second, they were “blown away.”

Fox’s initial design document framed the game as Rebel Rescue, a scenario in which a small craft scoured hostile planets to locate and recover stranded pilots, in a nod to X‑Wing and Star Wars. Licensing restrictions, however, prevented any official Star Wars tie‑ins, and the concept had to be reimagined as an original setting. Early builds of the game lacked a firing mechanic, but sometime in 1983, when Lucas tried a prototype, he famously asked, “Where’s the fire button?” Weapons were added soon after, along with gun emplacements on the fractal mountains and flying saucers to challenge the player. The procedural terrain, generated with Carpenter’s fractal algorithms, added a sense of vast, alien emptiness and introduced one of gaming’s earliest jump scares.

A frightening little fellow. One of gaming’s earliest jump scares with kind regards of George Lucas.

Sometimes, when landing to rescue a seemingly stranded pilot, the figure would leap toward the ship and suddenly reveal itself, right in your face, as an alien in disguise, complete with a terrifying scream, an idea that came from Lucas.

The creatures themselves earned the nickname “Jaggies,” derived from the jagged, stepped edges seen in early computer graphics due to limited resolution and color depth. The game’s working title, Behind Jaggi Lines, referenced both the alien foes and the angular struts of the cockpit window. However, Atari’s marketing team failed to appreciate the nerdy in-joke. In the end, the game was released as Rescue on Fractalus!, a name that conveyed both the peril and excitement of alien landscapes, while quietly preserving the team’s geeky humor.

Rescue on Fractalus! was like Ballblazer, developed early on but didn’t see public release until 1985 when released by Epyx.

The game was ported to the Apple II and Commodore 64 in 1985, with versions for the Atari 5200, Amstrad CPC, ZX Spectrum, MSX, and TRS-80 CoCo arriving the following years.

Players pilot a rugged fighter craft to locate and rescue downed pilots, across a world rendered with groundbreaking fractal 3D terrain, never knowing whether a desperate ally or a deadly alien waits outside the canopy,.

Nearly a year before being published, both Ballblazer and Rescue on Fractalus! were publicly demonstrated at the 1984 Summer Consumer Electronics Show (CES) held June 3–6 at McCormick Place in Chicago. The show floor drew nearly 100,000 visitors that year, an enormous stage for the Games Group. At the booth alongside other consumer‑electronics heavyweights, the titles drew attention for their smooth first‑person motion, split‑screen multiplayer, and real‑time soundtrack innovations. Journalists and attendees noted that the games felt more like miniature cinematic experiences than typical home‑computer fare. The reactions were excited but cautious, impressive technically, yet the commercial future of home computer gaming was still somewhat unsure.

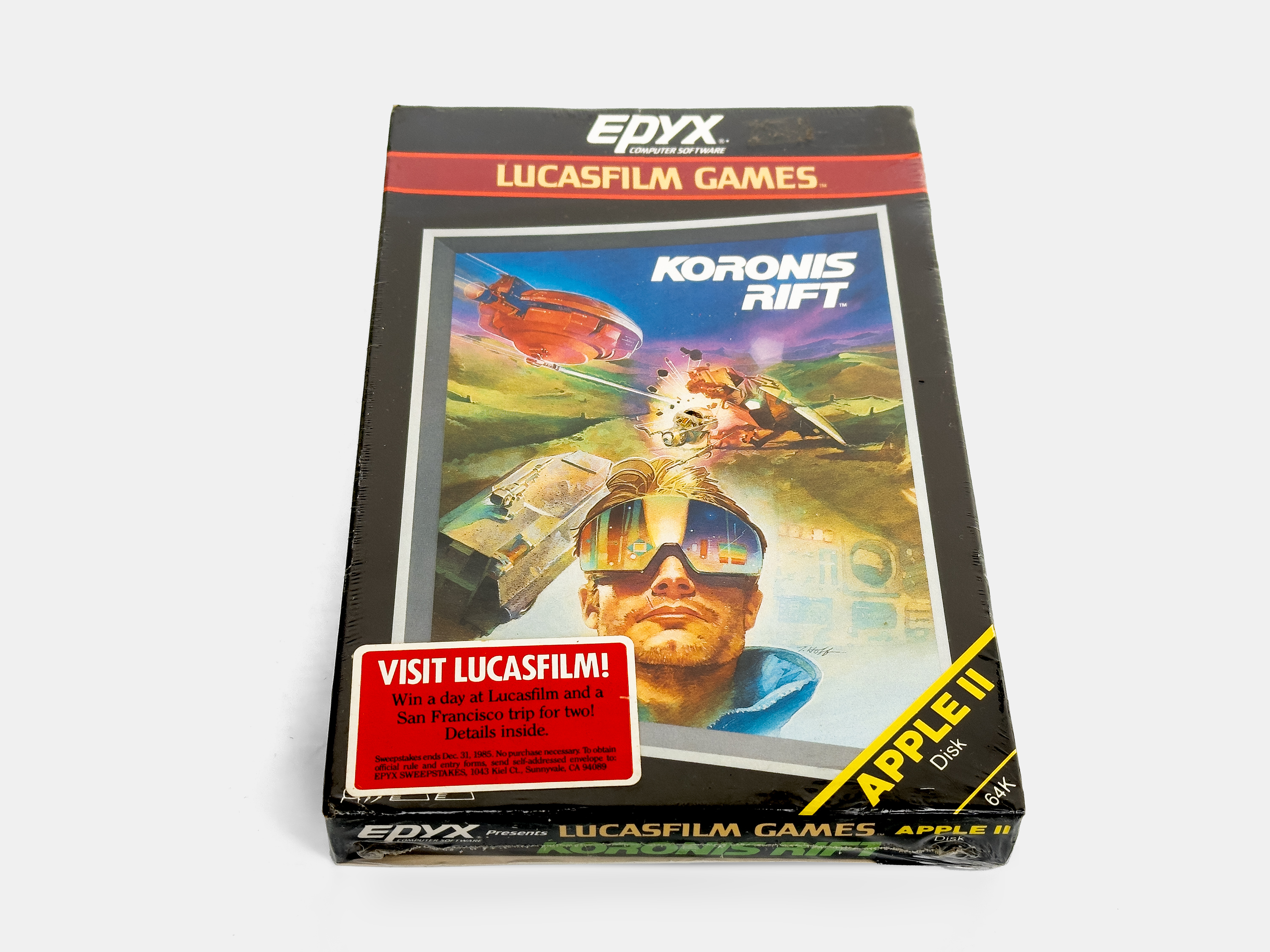

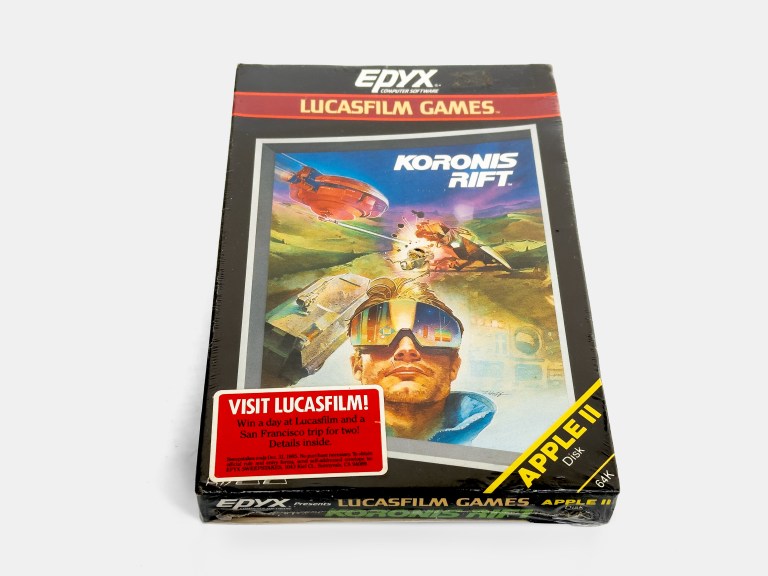

Following Rescue on Fractalus!, Lucasfilm Games turned its attention to Koronis Rift, a project led by Falstein, who sought to push beyond the adrenaline of dogfights into more layered, strategic gameplay. While the game reused Carpenter’s fractal terrain engine, it added a depth of planning and exploration that the team had only hinted at before. Players controlled a rover on an alien world, tasked with uncovering and salvaging Ancient technology while sending droids to analyze objects, upgrading their ship’s systems, and engaging hostile saucers. Combat was no longer a simple matter of shooting everything in sight. Each weapon was effective against specific classes of enemies but nearly useless against others, requiring players to observe, experiment, and adapt. The sense of discovery was as central to the experience as the action itself. The vast, mist-shrouded landscapes invited careful exploration, giving a feeling of isolation and wonder that was quite rare for games of the era.

Technically, Koronis Rift represented a quiet leap forward for the studio. The team combined fractal generation with Atari GTIA Mode 9, a graphics mode on the Atari 8‑bit computers that combined the Graphic Television Interface Adapter chip’s advanced color and sprite capabilities to create an atmospheric depth illusion, letting mountains recede into mist and enhancing the planet’s alien character. The visual cues were subtle but important, and in many ways marked Lucasfilm Games’ evolution from spectacle-driven titles toward games that blended technological ingenuity with thoughtful design and atmosphere, a philosophy that would continue to define the studio’s work throughout the 1980s and 1990s.

Koronis Rift marked the next step for Lucasfilm Games when released by Epyx in late 1985.

The game was developed for the Commodore 64 simultaneously with a version for the Apple II, also arriving in 1985. Versions for the Amstrad CPC, ZX Spectrum, MSX, and TRS-80 CoCo arrived in the following years.

Powered by the fractal engine used in Rescue on Fractalus!, in Koronis Rift players command a high-tech rover across an alien wasteland, scavenging ancient vehicles for lost technology while fending off alien saucers.

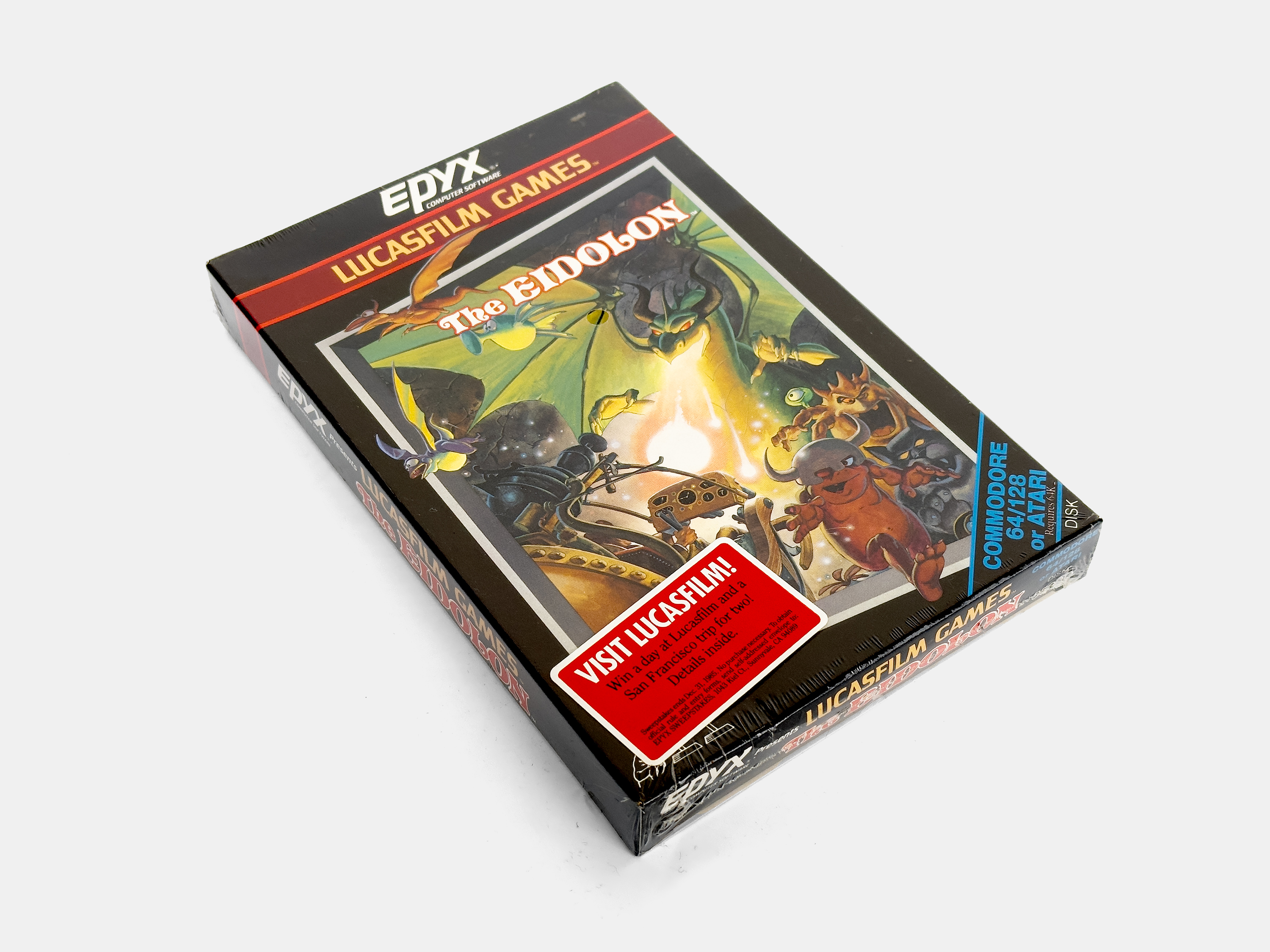

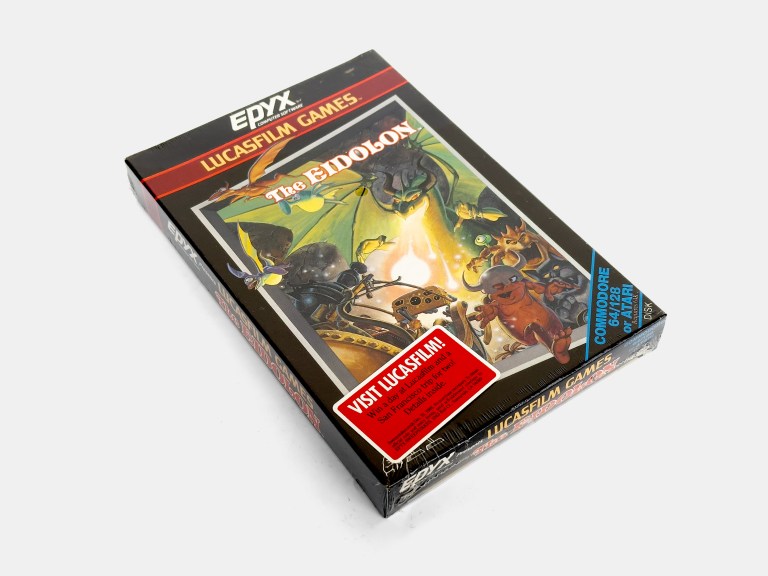

The fourth and last Lucasfilm Games title to be published by Epyx, The Eidolon emerged as a radical reimagining of the fractal technology first seen in Fractalus! Kellner, building on Carpenter’s original fractal engine, reversed the terrain algorithm to create subterranean labyrinths instead of mountains and valleys, turning the very idea of landscape inside out. The project had its origins in Kellner’s early design notes for The Dragon Game, in which players controlled a dragon navigating a fantasy world. Over time, the concept evolved into a Victorian‑inspired fantasy, where a daring inventor tunnels into the recesses of his own mind, exploring cavernous depths, battling bizarre creatures, and ultimately confronting dragons that embodied different kinds of magical challenges.

Winnick, already known for his visual flair, devised a clever cell-animation system to bring the creatures to life. Each character, whether dragon, troll, or flying hybrid, was composed of separate body parts, wings, tails, and heads, which were layered meticulously every frame to conserve precious memory. The method allowed the team to populate the screen with a surprising variety of enemies, despite the limitations of the 6-year-old Atari 8‑bit hardware. The titular machine, the Eidolon, was a steampunk-inspired contraption, its cryptic control panel leaving players to learn through trial and observation rather than relying on a manual.

Kellner later reflected that while the dragons’ movement was limited due to technical constraints, the team had accomplished something remarkable, crafting a deeply atmospheric, visually arresting world that felt far larger and more intricate than the hardware could reasonably allow. The Eidolon stood as both the culmination of Lucasfilm Games’ experiments and a testament to the inventiveness, technical daring, and artistic vision of its small but extraordinary team.

The Eidolon, released in December of 1985, was the final entry in Lucasfilm Games’ first quartet of experimental titles, and the last to be published by Epyx.

The Eidolon was ported to the Apple II and Commodore 64 in 1985, with versions for the Amstrad CPC, ZX Spectrum, MSX, and NEC PC-88 arriving the following years.

Using an inverted iteration of the fractal engine from Rescue on Fractalus!, The Eidolon delivered a strange, labyrinthine first-person adventure featuring dragons, color-coded energy blasts, and an imaginative Victorian-inspired sci-fi shell.

With experimentation and originality, Lucasfilm Games established a philosophy that would come to define the studio for the following decade. Games that stood on their own, independent of existing licenses, while pushing the boundaries of storytelling. The early limitation of not being able to draw on Star Wars or Indiana Jones proved an unexpected advantage, forcing the team to build from scratch, to invent mechanics, and forge their own intellectual properties. As the studio later reflected, “we had to build something from the ground up.” That insistence on originality became a cornerstone of Lucasfilm Games’ identity.

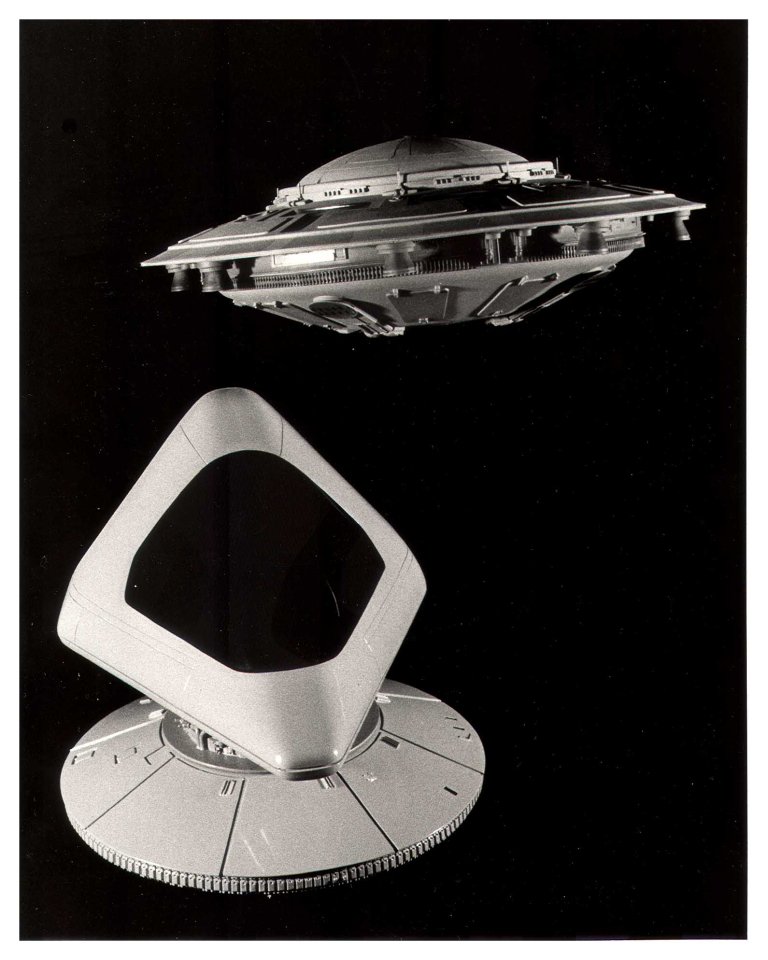

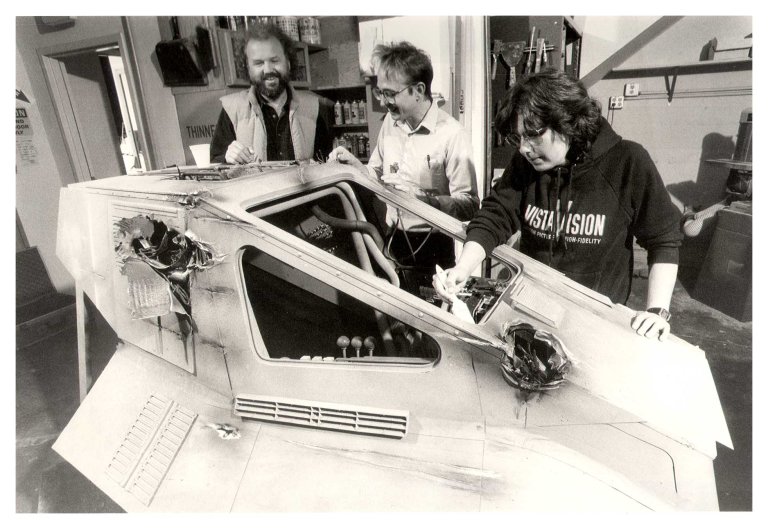

Just as the parent company had mastered visual effects, sound design, and world-building on the big screen, the Games Group approached interactive entertainment with the same rigor. Every ship, vehicle, and environment was treated with cinematic care, designed to feel believable and engaging, and the integration of film-studio expertise was tangible. The team drew inspiration from Industrial Light & Magic, sound engineers, and model makers. Cockpit mockups, physical miniatures, and analog recordings informed prototypes. The Valkyrie fighter in Rescue on Fractalus! drew on Lucasfilm model research, with Fox referencing X‑Wing instrument panels stored at Industrial Light & Magic’s warehouse to make the cockpit and ship systems feel authentic.

As the games were built from the ground up with meticulous care, they carried a sense of fidelity and internal consistency uncommon for early 1980s gaming. Whether piloting a rotofoil, flying a Valkyrie, exploring the rifts of Koronis Rift, or navigating the cave systems of The Eidolon, players interacted with systems that behaved believably.

Top image: A model of the Ballblazer “Rotofoil” hovercraft and “Jaggi” suicide saucer from Rescue on Fractalus.

Bottom image: A model of the Valkyrie Class fighter from Rescue on Fractalus!,

The models, built by Lucasfilm technical experts, were crafted following the completion of the games in 1984, for use in manuals, packaging, and marketing.

Images from the Atari/Lucasfilm Press Kit – Langston.com

Amid industry turbulence, Lucasfilm Games pressed forward. After the collapse of the Atari deal, delayed releases, and beta versions circulating on bulletin boards, Ballblazer and Rescue on Fractalus! finally reached the public through Epyx in 1985. Just a year later, the studio released its first licensed adaptation with Jim Henson and George Lucas’ Labyrinth. In 1987, Lucasfilm Games self-published its first title, Maniac Mansion, launching a decade of some of the most beloved and influential adventure games.

For Peter Langston, David Fox, Noah Falstein, Gary Winnick, Charlie Kellner, and David Levine, these first titles became stepping stones toward careers that would shape gaming and digital media. For George Lucas, they proved that imagination, technology, and narrative could converge in a wholly new medium.

Sources: Steve Bloom’s article in Computer Games Vol. 3 December 1984, Wikipedia, Retrogamer, Data Driven Games, Antic Magazine August 1984/December 1985, LucasArts.com, langston.com, electriceggplant.com, Jedi News, Escapist, fanthatracks, COMPUTE!, Zzap!64…