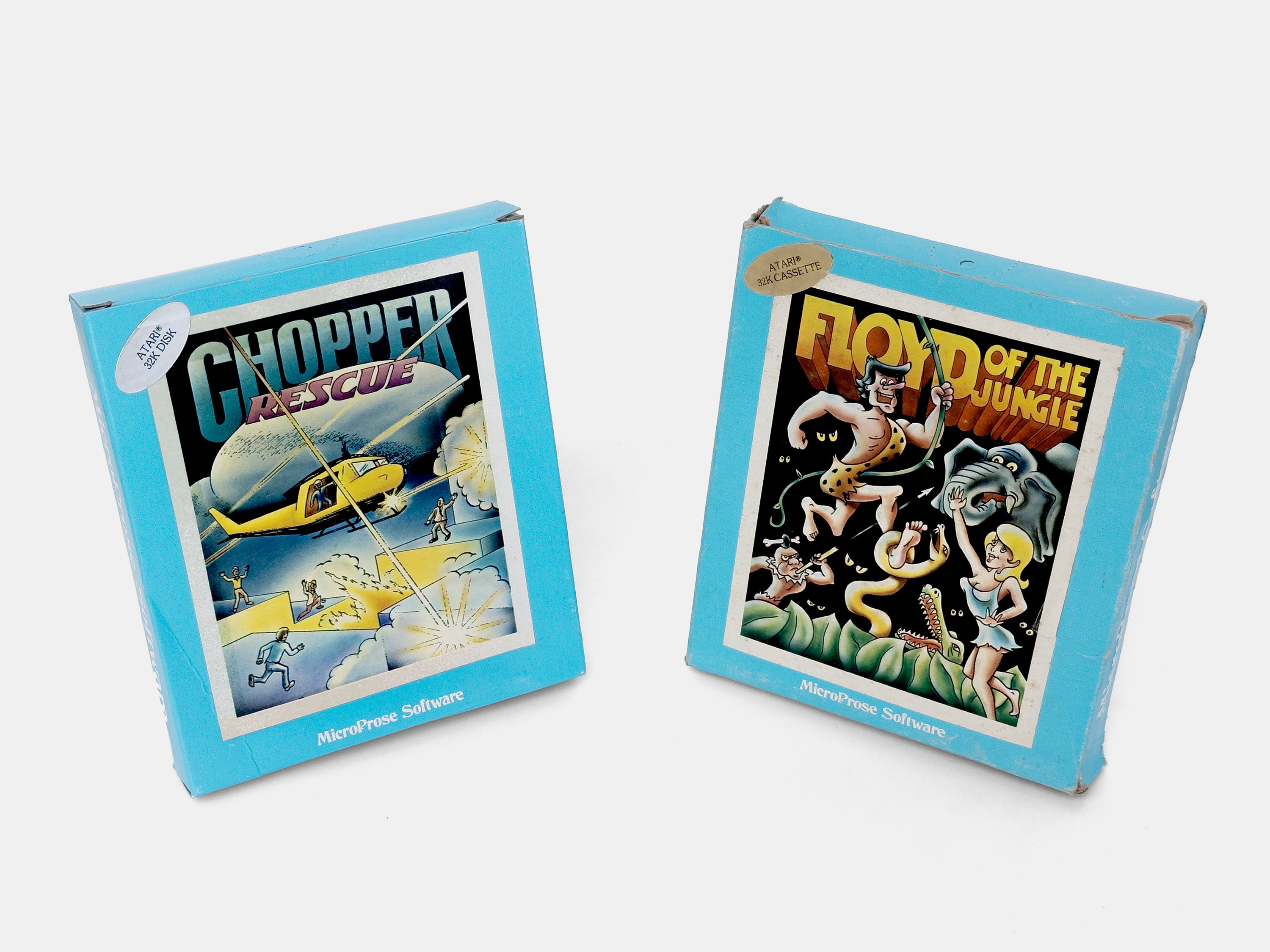

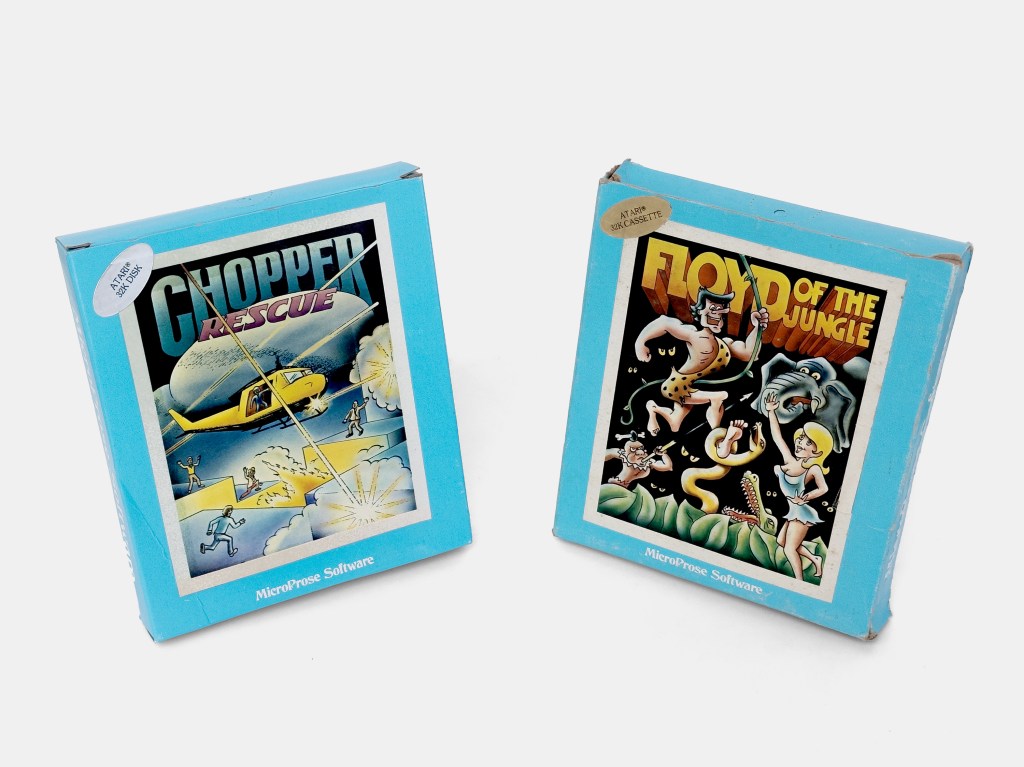

In 1982, MicroProse advertised its first batch of games under the headline “Experience the MicroProse Challenge!!!” The three games, all written by Sid Meier for the Atari 8-bit family of home computers, included Hellcat Ace, Chopper Rescue, and Floyd of the Jungle.

After nearly a year of detective work, a group of determined MicroProse employees successfully tracked down a legendary video arcade cabinet, the very machine that had inspired the company’s founding. The MGM Grand Hotel and Casino, where co-founders John Wilbur “Wild Bill” Stealey and Sidney Meier first met and squared off in digital dogfights back in 1982, had changed hands in 1986, and its once-bustling arcade had long since been dismantled. Luckily, unlike most machines, it hadn’t been sold off or, even worse, scrapped, but was hiding in the hotel’s storage under years of dust, forgotten but intact. With persistence and a few well-placed connections inside Bally Corporation, the hotel’s then-owners, the employees secured the vintage cabinet and presented it to the MicroProse founders at a company gathering in 1988.

It was a fitting tribute to the company’s origin story, a brief moment in a Las Vegas hotel arcade that sparked one of the most influential partnerships in gaming history. A story of two men from entirely different walks of life, who together created one of the most important game companies of the decade, one that would define a generation of simulation and strategy games.

Sid Meier, sitting, and Bill Stealey pose in 1988 with the original Red Baron arcade cabinet, the same machine that, six years earlier, sparked their partnership and led to the founding of MicroProse.

Image from The Digital Antiquarian.

In May 1982, during a General Instrument corporate sales conference at the MGM Grand in Las Vegas, two employees, “Wild” Bill Stealey and Sid Meier, found themselves looking for a break from the day’s presentations. Meier suggested they skip out early to explore the hotel’s arcade, and the two quickly turned the afternoon into a friendly rivalry, competing across a variety of titles, with Meier winning each time. Stealy eventually challenged Meier to compete in Red Baron, Atari‘s 1981 World War I flight simulation game. Stealey, confident in his aviation skills and with a wealth of real flying experience, was caught off guard when Meier effortlessly mastered the game.

While Stealey approached the game like a pilot, Meier, already dabbling in game design as a hobby, treated it as a programmer and designer. He showed an uncanny ability for predicting its next moves, consistently outscoring Stealey by decoding the game’s patterns and mapping out the enemy’s maneuvers. That afternoon in Las Vegas, Meier calmly dismantled both Red Baron’s mechanics and Stealey’s ego, finally remarking that he could write a better version in a week. Stealey laughed, undeterred, and raised the stakes: “If you can write it,” he shot back, “I can sell it.”

Red Baron, developed by Atari and released in 1981, ran on a black-and-white 19-inch Electrohome vector monitor with a blue overlay. Its back glass allowed bystanders to watch the dogfighting action, turning the arcade cabinet into a mini spectacle.

Meier’s fascination with games began in childhood, when he spent hours inventing rules and scenarios with toy soldiers and building blocks. He was less interested in following the rules than in understanding how things worked, a mindset that would serve him well once computers entered the picture. The microcomputer boom and the rise of coin-operated arcades in the 1970s would soon give him the perfect outlet.

In 1971, Meier enrolled at the University of Michigan with broad interests in chemistry, physics, and mathematics. Looking to earn extra money, he applied for a work-study job with physics professor Noah Sherman, who was experimenting with the then-novel idea of computer-assisted learning. Meier was already taking a programming course, and Sherman hired him with the expectation that he could learn on the fly. The experience jump-started his interest in computing. He began teaching himself programming on HP calculators, and by the time he graduated in 1975 with a degree in computer science, he had discovered his calling.

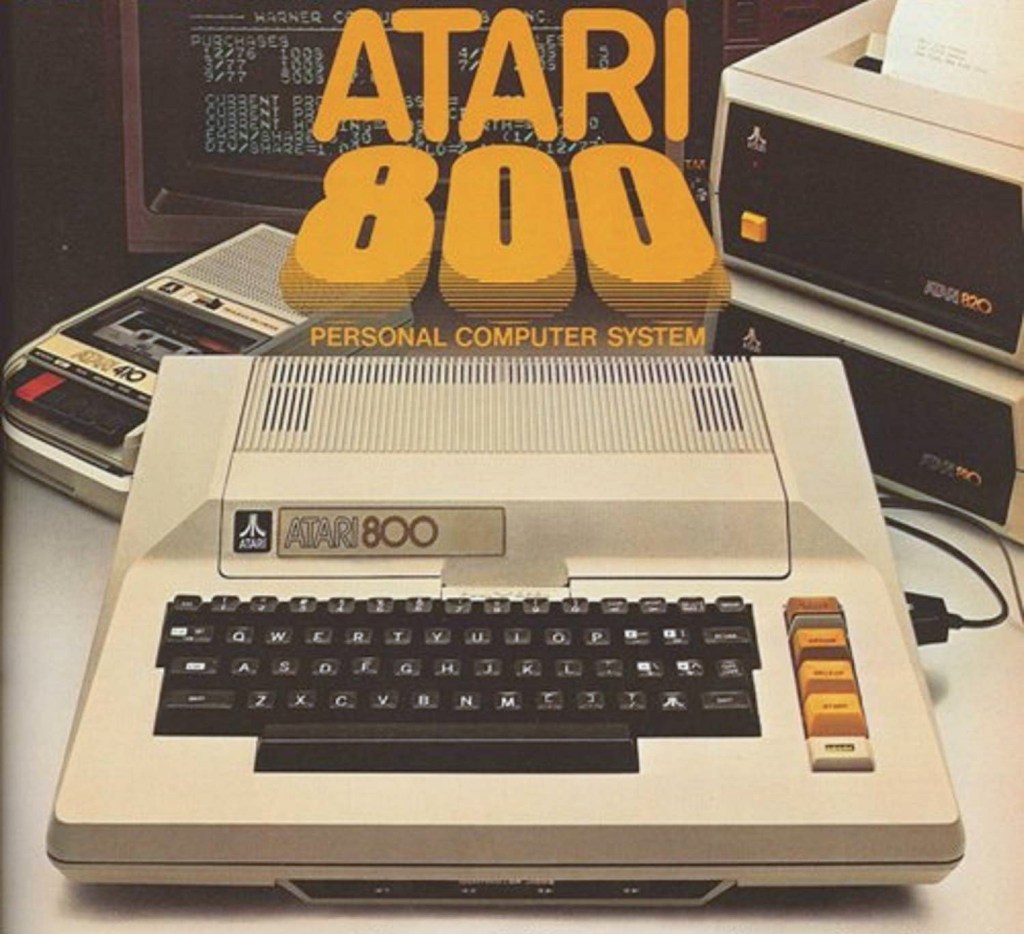

After college, Meier joined General Instrument Corporation as a systems analyst, installing networked cash register systems in retail stores. The work was steady but uninspiring, and during downtime, he amused himself by coding a Star Trek–style game that soon spread among coworkers. Still, he held off buying a personal computer of his own until Atari’s sleek 400 and 800 models arrived in 1979. By 1980, he brought home an Atari 800 and began coding in Atari BASIC. His first creation, Hostage Crisis, was a simple four-color shoot-’em-up in which players fired missiles at a giant, looming face nicknamed the “Ayatolla,” inspired by the Iran hostage crisis then dominating the headlines.

The Atari 800, released in 1979, was a powerful and accessible home computer. It and its smaller brother, the Atari 400, stood out among early home computers for their dedicated graphics and sound chips, which allowed more sophisticated visuals and audio than contemporaries. By 1980, Sid Meier had brought one home and began coding in Atari BASIC.

One evening, Meier gathered his parents in the living room to showcase his latest creation. His mother, who had never held a joystick, humored him at first with the polite enthusiasm parents reserve for their children’s projects. But as she played, something unexpected happened. Her excitement gave way to concentration, her jaw tightening, her body leaning instinctively with the on-screen movements as if dodging the missiles herself. It was a small, almost private moment, but it confirmed to Meier that games could capture the imagination across generations.

He continued refining his craft by cloning popular arcade hits like Space Invaders and Pac-Man, not for profit but as exercises in learning design and code. Hoping to connect with other hobbyists, he formed a small, informal Atari user group, quirkily named SMUGGERs – Sid Meier’s User Group for Atari computers.

Most of his early creations were crude but promising, coded late at night after his day job at General Instrument. Some he slipped into plastic baggies and sold through a local electronics shop. By 1982, he broke through with his first official release, Formula 1, published by Acorn Software Products.

In contrast to Meier, Stealey was loud, confident, all charisma and hustle. A fighter pilot turned corporate strategist, he knew how to pitch and promote, making something seem bigger than it was. Where Meier saw code, Stealey saw market potential. He had entered the Air Force Academy determined to become a pilot, and did, glasses and all. For six years, he flew on active duty before spending another decade with the Air National Guard. He started out instructing in nimble T-37 trainers, then moved on to the lumbering C-5A Galaxy. But cargo planes didn’t make generals. So he left active duty, kept flying on weekends, and set his sights on graduate school. Initially headed for law, a fellow Academy grad steered him toward business instead.

Consulting followed, first at Cresap McCormick & Paget in New York, then at McKinsey. But Stealey lacked the patience for corporate consulting. He wasn’t wired for slow. After three years, he joined General Instrument in Hunt Valley, Maryland, as director of strategic planning for a $250 million division. Weekdays, he was buried in spreadsheets and strategy. Weekends, he was back in the cockpit, flying A-37 Dragonfly attack jets with the Pennsylvania Air National Guard.

At General Instrument, surrounded by engineers still doing everything by hand, Stealey put his mix of brains and impatience to work. Back at Cresap, he had already built a remote dial-up financial modeling tool, essentially an early spreadsheet system, before personal computers made them common. Now he saw how computing could streamline corporate planning, which in early 1982 led him to buy an Atari 800. Not for games, but for VisiCalc.

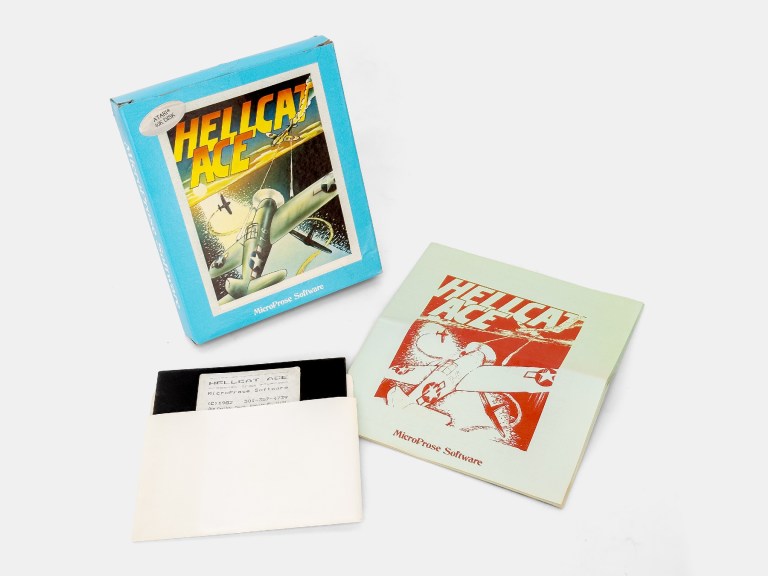

After the Las Vegas conference, Meier went back to Maryland, and set to work on what became Hellcat Ace, a World War II flight simulator modeled after the Grumman F6F Hellcat. True to programmer bravado, it didn’t take a week as promised, but a few months. The result was lean, fast, and surprisingly authentic for a home computer game. Meier handed it to Stealey, who play-tested it with the eye of a pilot, marking up bugs and military inaccuracies. A week later, Meier returned with an updated version.

Once satisfied, Stealey prepared his pitch and brought the prototype to Tom Disch, a computer store owner in New York. He walked out with a handwritten order for 50 copies. The partnership was now a business. Operations shifted to Stealey’s basement, and the two formed a company. After discarding names like “Smuggers Software,” drawn from Meier’s Atari user group, they settled on “MicroProse”. It sounded technical, sharp, and professional, despite its confusing similarity to MicroPro, another software firm. That confusion lingered until 1989, when MicroPro rebranded as WordStar.

In October 1982, with the final version of Hellcat Ace packed in a plastic bag with a mimeographed cover, manual, and cassette tape, Stealey walked into a sales call and walked out with an order for 100 copies. Still working full-time at General Instrument, he became a traveling salesman by night, lugging copies on business trips and pitching to computer stores whenever he could.

When orders began to roll in, Meier spent hours at his Atari manually duplicating disks, each one taking a full minute during which the machine could do nothing else. Soon, they hired a teenager from the user group at 25 cents per disk, freeing Meier to return to what he did best, making games.

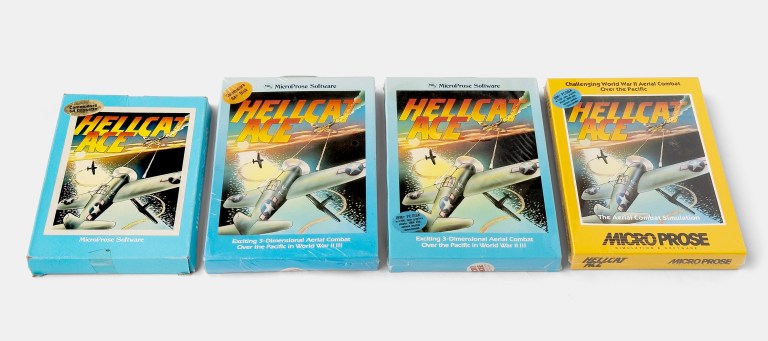

MicroProse quickly abandoned its improvised bagged copies for printed, shelf-ready boxes. The shift was driven by Stealey’s retail push, where professional packaging was no longer optional but essential. A proper box made the games easier to sell and gave the brand a more polished identity. The move mirrored a broader industry trend of the early 1980s, as many small developers traded zip-lock bags and hand-assembled kits for printed boxes.

Hellcat Ace, MicroProse’s debut game, was published in the fall of 1982 for the Atari 8-bit line of home computers.

Shown here is the boxed Atari version, the company’s earliest boxed retail packages, issued alongside Floyd of the Jungle and Chopper Rescue.

Hellcat Ace was a fast, no-frills combat flight simulator set in the Pacific theater of World War II. The graphics were primitive, blocky, and flat, even by the standards of 1982, but the soul of the game wasn’t its visuals. It was its feel.

A mission dropped the player into the cockpit of a Grumman F6F Hellcat, typically cruising at 10,000 feet over the Pacific, flying north at 200 mph. The first scenario, Flying Tiger, was a kind of tutorial masquerading as a mission. A lone Japanese bomber drifting into your gunsight, conveniently level and directly ahead, making it an easy target for a single, satisfying burst. From there, the challenge ramps up with later missions introducing increasingly nimble enemies and new dogfighting dynamics. Get 5 victories and you become a Hellcat Ace.

Stealey managed to get Antic, a magazine dedicated to Atari 8-bit computers, to review Hellcat Ace in its May 1983 issue. The verdict: modest visuals, strong fundamentals. “While the graphics are not stunning,” the reviewer wrote, “the game plays well and holds your interest with multiple skill levels and a variety of scenarios.” They praised the fluidity of the controls, “Fancy aerobatics are easily done with loops, barrel rolls, split ‘S’ and Immelman turns being possible”, and concluded that while the game could benefit from sharper graphical effects, its playability made it a clear recommendation for anyone interested in flight simulators. For MicroProse, it was the first taste of real national exposure.

As Hellcat Ace began to circulate, Meier quickly followed it with Chopper Rescue, a fast-paced hybrid of Defender and Berzerk. Players piloted a helicopter through tight mazes, dodging cannons and alien ships, racing against the clock to extract stranded teammates. It was more arcade than simulation, a sign that Meier was experimenting with different design styles.

Chopper Rescue was a fast-paced, arcade-inspired action game that had players piloting a helicopter through tight mazes, dodging cannons and flying enemies while racing against the clock to rescue stranded allies. Unlike Meier’s flight simulator, it emphasized reflexes and immediate thrills that captured the excitement of early 1980s coin-op games.

That experimentation carried directly into his third game, Floyd of the Jungle, a hard swerve away from aviation and into pure, chaotic fun. Inspired partly by the latest Tarzan movie airing on TV and partly by animation tools Meier had been tinkering with, the idea merged into a jungle adventure filled with multiple characters, colorful effects, and slapstick action. “There was this movie on TV, the latest Tarzan movie with Bo Derek,” Meier recalled, “and I was also working at the time with some animation tools that I’d been developing, animation effects with multiple characters and multiple player/missile images, and the two just merged together.”

Floyd of the Jungle stood out for supporting up to four players on the same computer, a rare feature at the time. It was chaotic, loud, and above all, social. While Meier’s first two games had been straightforward and mostly solitary experiences, Floyd was designed to be shared. You needed friends, fast fingers, and a willingness to yell at each other while hammering the keyboard. It quickly became Stealey’s favorite demo when pitching to computer stores, because it filled a room with laughter and noise.

Following the release of Hellcat Ace, Meier created Chopper Rescue and Floyd of the Jungle, both released for the Atari 8-bit in the latter part of 1982.

MicroProse’s first advertising campaign carried the slogan: “Experience the MicroProse Challenge!!!” and featured the three Meier-designed titles for the Atari 8-bit line, Floyd of the Jungle, Chopper Rescue, and Hellcat Ace.

Image from Atarimania.

From the start, the division of labor was clear. Meier focused on development, and Stealey ran the business. MicroProse became profitable in its second month. By 1983, Hellcat Ace and Floyd of the Jungle were getting their first reviews. They weren’t glowing, but Stealey didn’t care. He had a plan. He began selling the games through old-fashioned telemarketing, often cold-calling electronics stores under fake names to ask if they carried MicroProse titles, only to call again moments later as a “sales rep” offering to ship copies. He kept this up for over a year. It was textbook Wild Bill. Charm, audacity, and just enough truth to close the deal. In 1983, he left General Instrument to work on MicroProse full-time. Meier followed a year later.

As 1982 turned into 1983, the personal computer market was shifting rapidly. Commodore’s newest machine, the Commodore 64, was selling like hotcakes, climbing from 350,000 units in 1982 to more than 1.3 million in 1983. It was clear that the C64 was becoming the dominant platform. MicroProse moved quickly, porting Floyd of the Jungle to the Commodore 64 that year, its first title for the platform, followed shortly by Hellcat Ace, adapted by Ron Verovsky and Don Awalt. IBM PC users would get their own version a year later. The ports not only broadened the audience but also demonstrated that MicroProse could adapt its lineup to new markets, a survival skill in the fast-moving early 1980s software scene.

Hellcat Ace was ported to the Commodore 64 in 1983 and the IBM PC in 1984, with subsequent releases continuing as late as 1986.

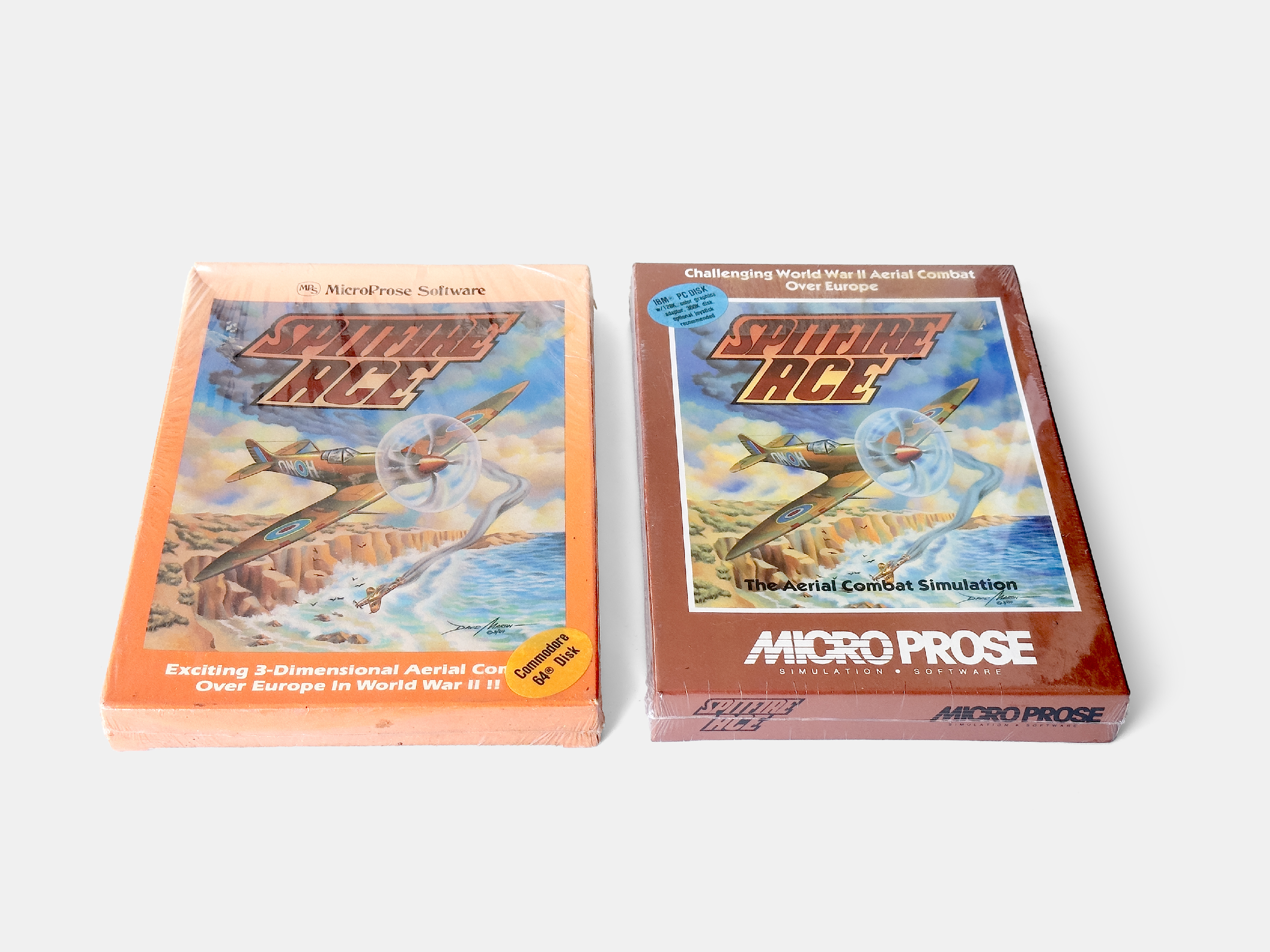

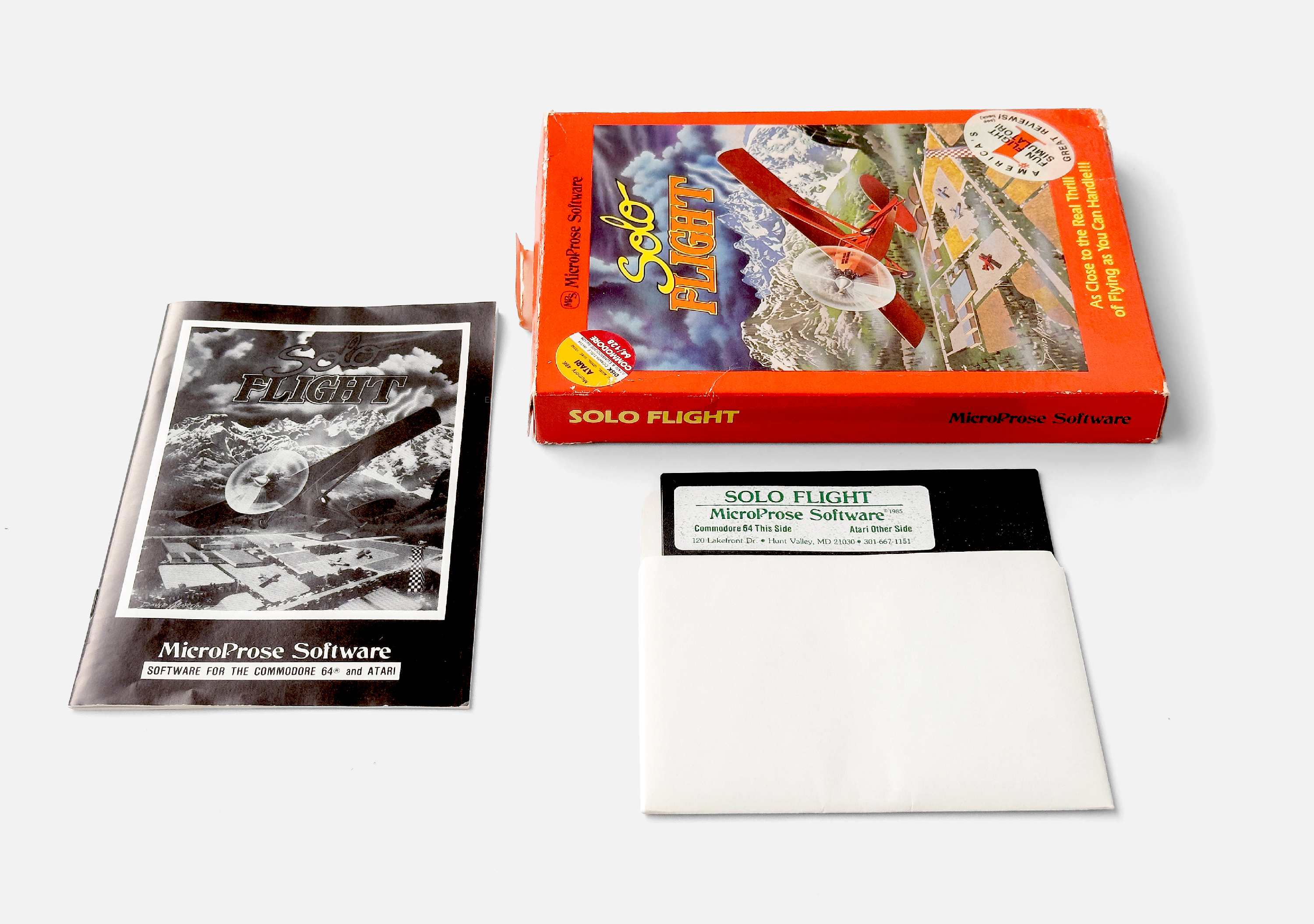

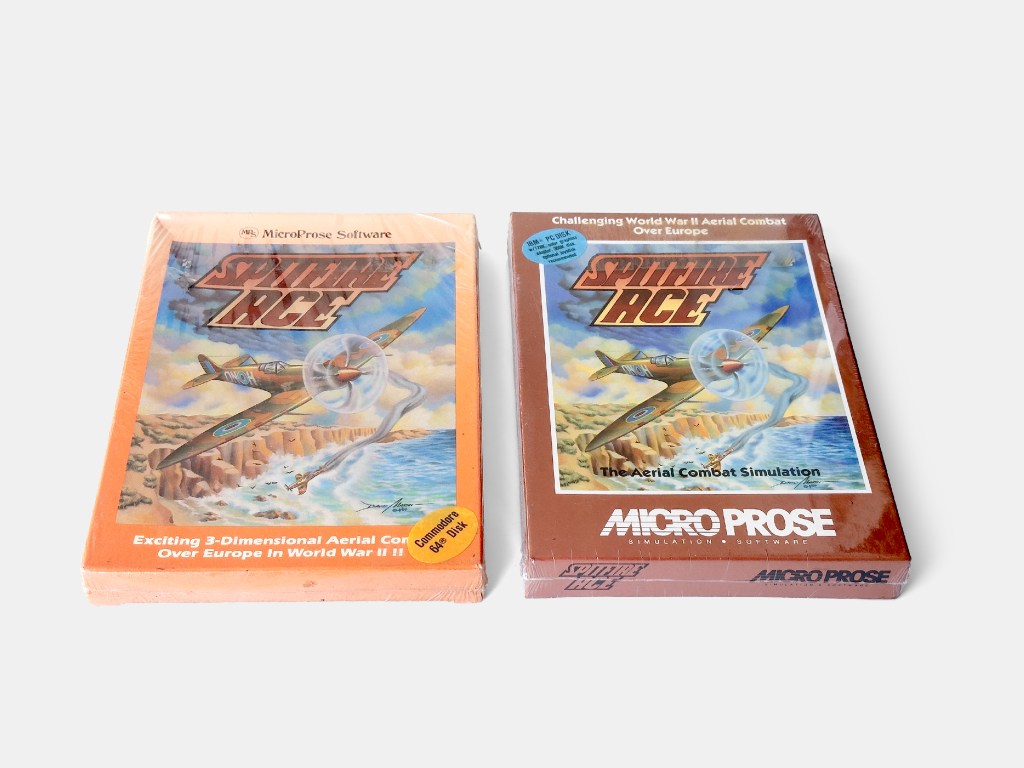

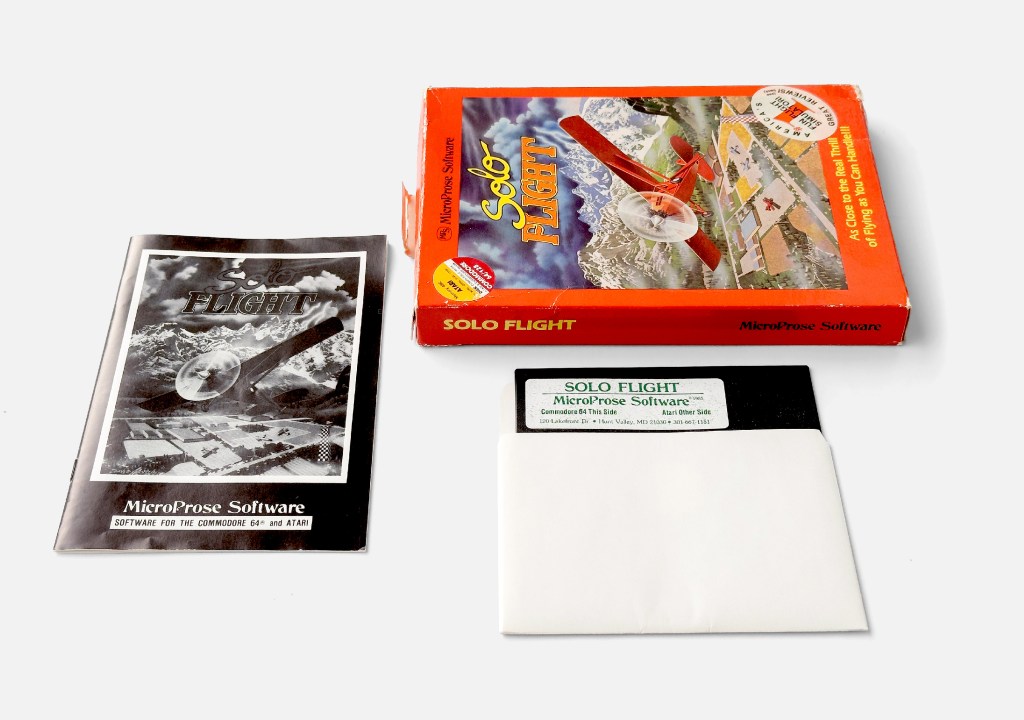

With the three games forming its initial lineup, it was Hellcat Ace that pointed to the company’s future. A second flight sim, Spitfire Ace, essentially a modified Hellcat Ace, followed in late 1982 for the Atari 8-bit and later the Commodore 64. In 1983, came Solo Flight, a civilian simulator that marked MicroProse’s first genuine commercial success.

Spitfire Ace, first released in 1982 for the Atari 8-bit and later ported to systems like the Commodore 64 and IBM PC, was essentially a refined version of Hellcat Ace. It kept MicroProse in the flight simulator market while the company prepared its first breakout success, Solo Flight.

Solo Flight, released in 1983, marked MicroProse’s first major commercial success. Building on the foundations of Hellcat Ace and Spitfire Ace, it offered players a more sophisticated civilian flight experience, helping establish the company as a leader in realistic flight simulation.

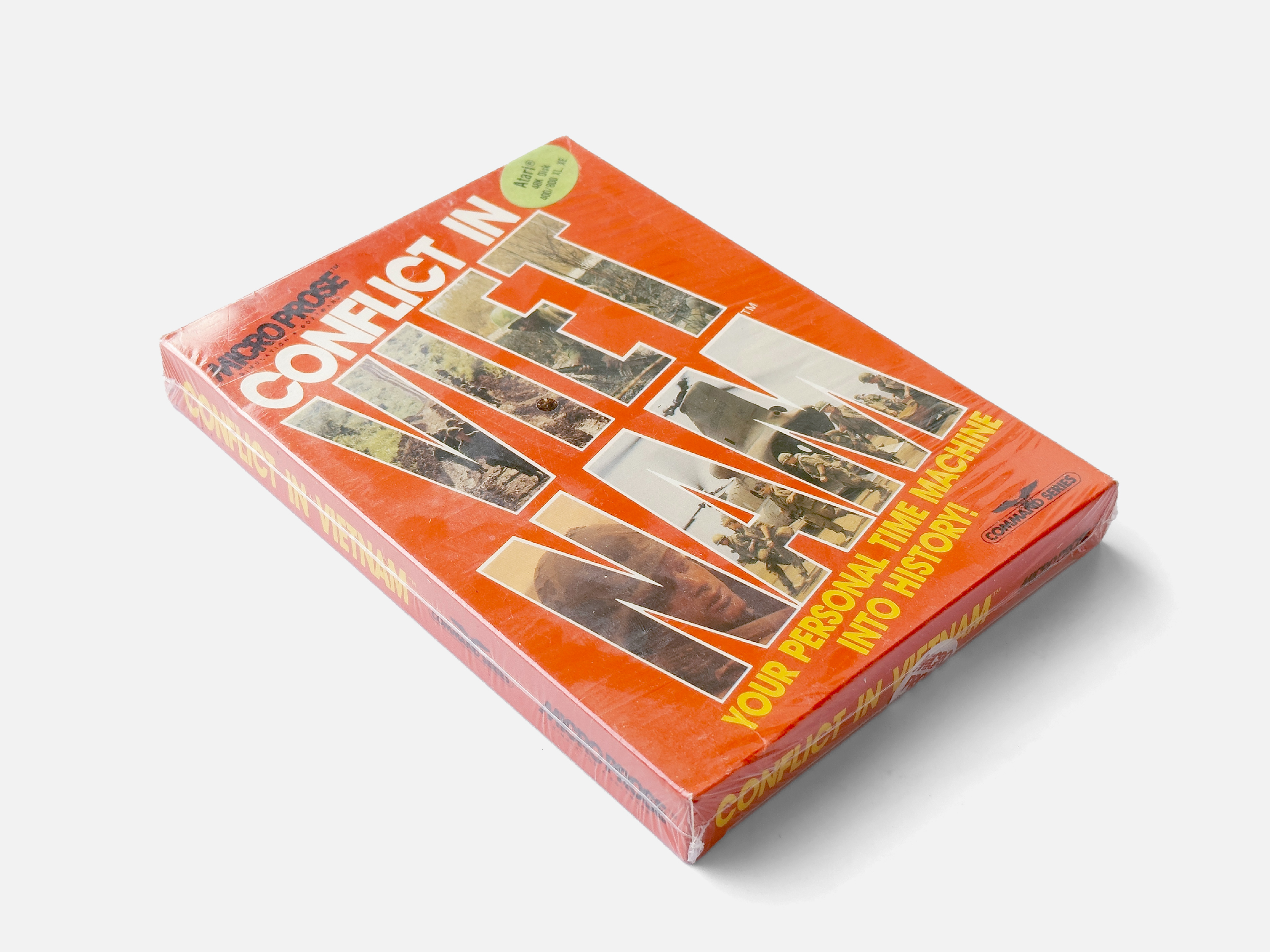

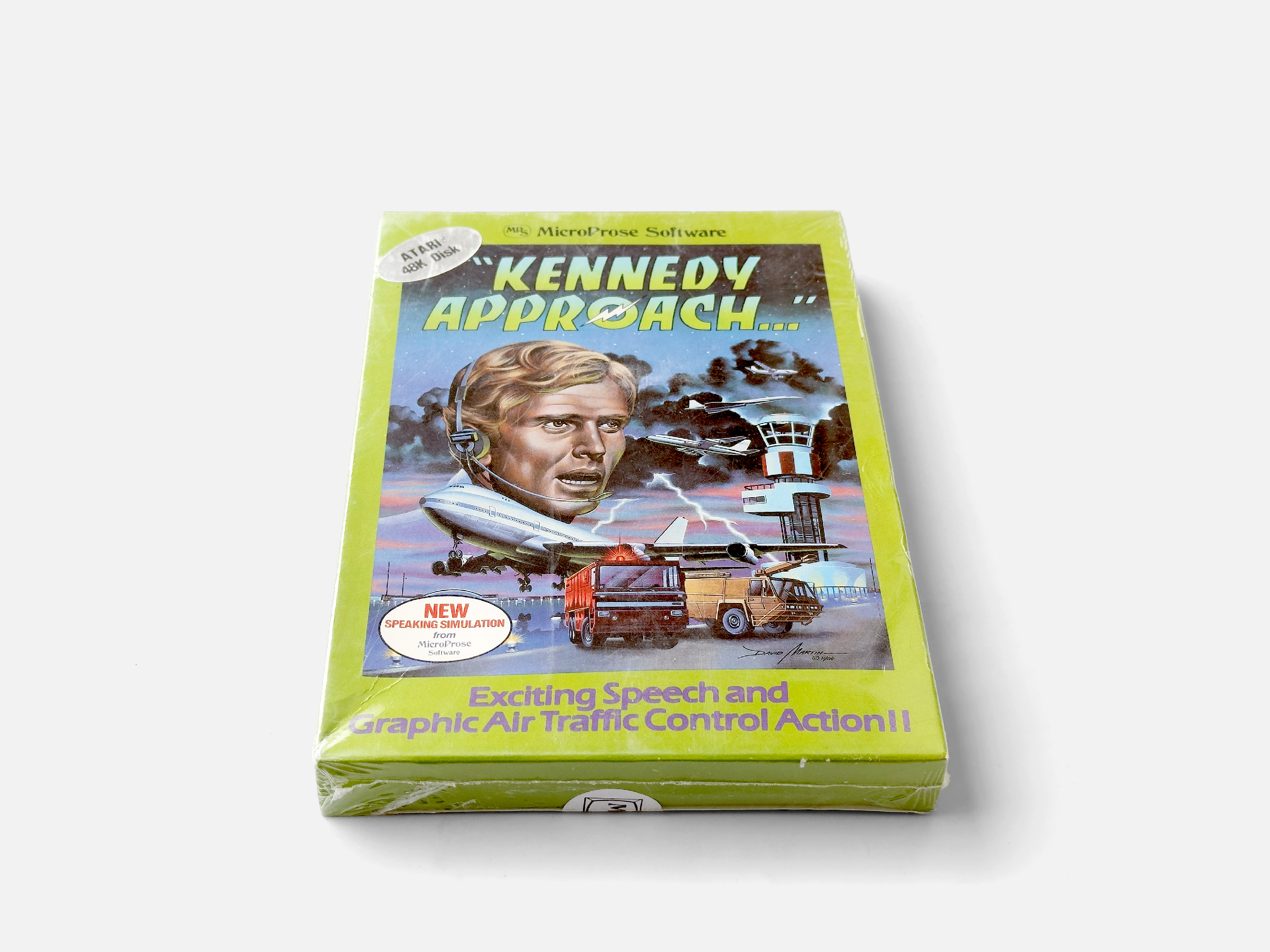

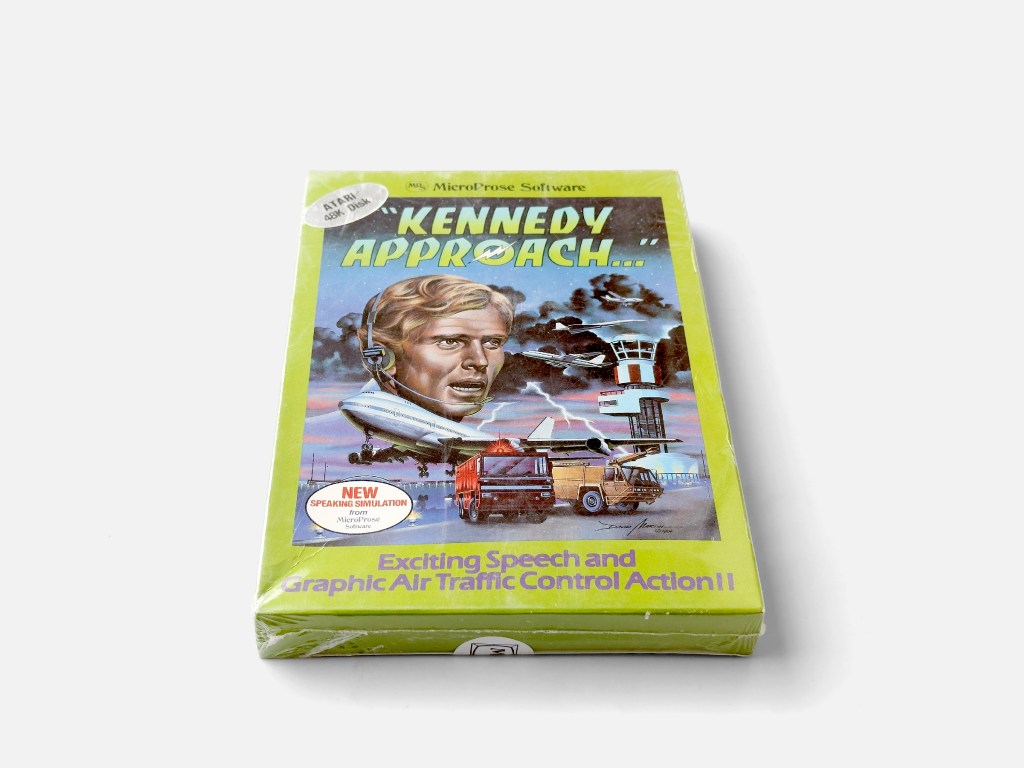

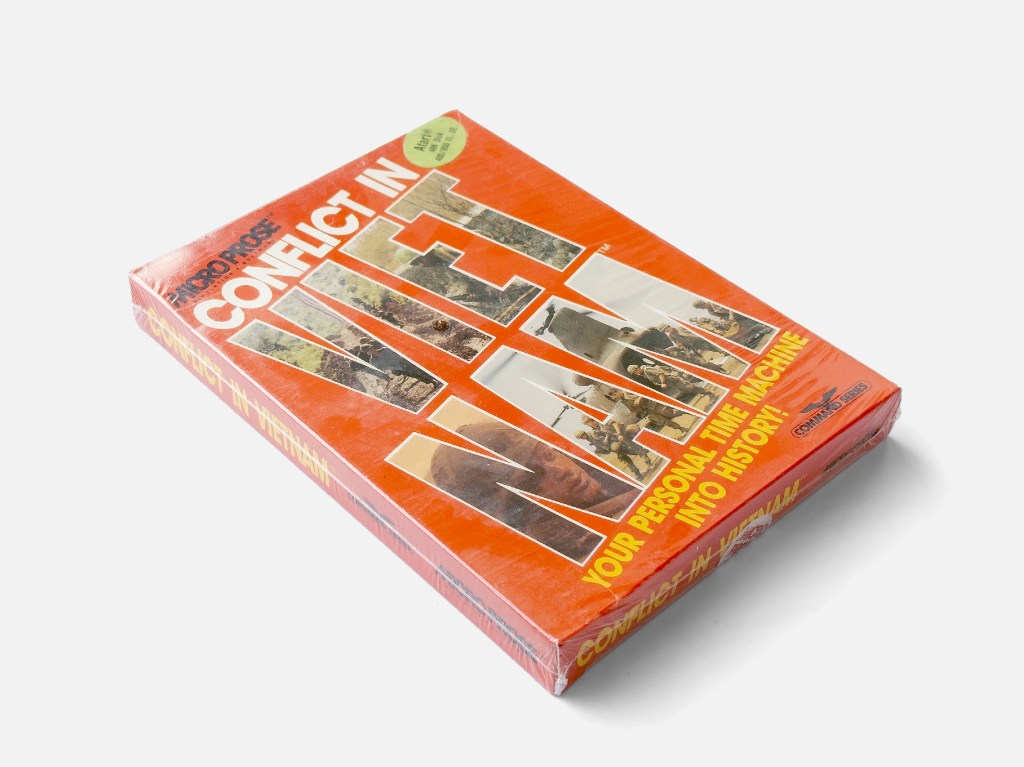

Momentum carried the company into the mid-1980s. Kennedy Approach, a unique air traffic control sim designed by Andy Hollis, arrived in 1985. Conflict in Vietnam followed in 1986, closing the book on the company’s Atari 8-bit development. The real breakthrough, however, had come with Solo Flight and later F-15 Strike Eagle. The latter quickly became a flagship franchise, eventually selling more than one million copies. Stealey, with his military background, gravitated toward realism-heavy simulations, while Meier, ever the strategist, leaned toward history and systems. Those inclinations would gradually steer MicroProse into new creative directions.

Kennedy Approach, released in 1985, was a unique air traffic control simulator that expanded MicroProse’s focus beyond combat and civilian flight. It challenged players to guide aircraft safely into New York’s Kennedy Airport, showcasing the company’s growing ambition for realism and innovative gameplay.

Conflict in Vietnam marked MicroProse’s final release for the Atari 8-bit line. For four years, the system had been the company’s backbone, but by the mid-1980s, its aging hardware, over seven years old, was being outpaced by newer platforms.

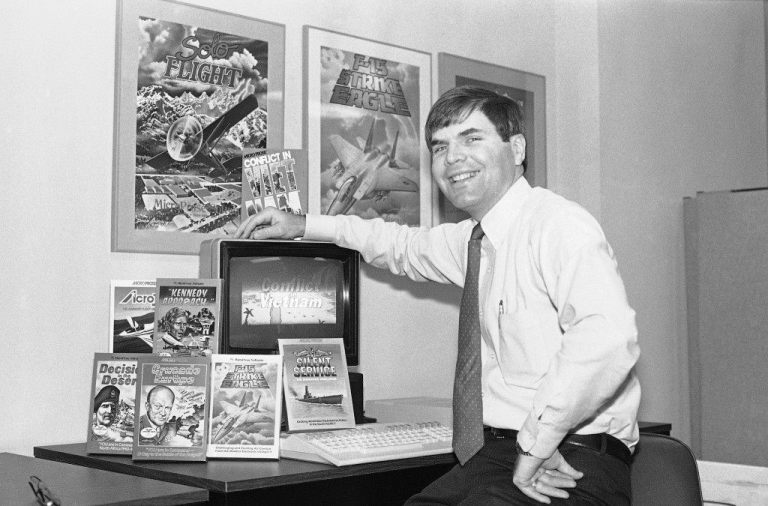

“Will” Bill Stealey, in front of MicroProse’s growing library of hits from the mid-to-late 1980s, a period when the company established itself as a leader in flight simulation and strategy games.

Image from Flashbak (AP Photo/Bill Smith).

By the late 1980s, Meier was drawing from his love of board games, particularly those published by Avalon Hill. With Stealey’s backing to secure the necessary permissions, he began developing games that married strategic depth with digital systems. The result was Railroad Tycoon and later Civilization, both groundbreaking, both deeply influential, with design DNA that would resonate across the industry for decades.

From a single game coded in a few weeks to a sprawling company employing over 500 people worldwide, MicroProse expanded rapidly. By 1991, it reported annual revenues of more than $45 million. That same year, it went public with a valuation exceeding $400 million, one of the most successful IPOs in gaming history. Civilization was released that year, a massive success, and it would go on to become Meier’s most recognizable work, a franchise that has since sold around 40 million copies.

But while the early 1990s were creatively rich for Meier, they were financially dangerous for MicroProse. The company made costly bets on an arcade division and an adventure game engine, investments that left it saddled with debt. In 1993, Stealey, a longtime friend of Spectrum Holobyte president Gilman Louie, negotiated a merger between the two companies. The move stabilized MicroProse but forced painful closures of satellite offices and large-scale layoffs.

In 1994, Stealey departed, remarking that “It was a great marriage, but the new company only needed one chairman.” MicroProse continued as a subsidiary under Spectrum Holobyte until 1996, when the parent company consolidated operations and made further cuts. Disillusioned by the corporate reshuffling, Meier left with Jeff Briggs and Brian Reynolds to found Firaxis Games. His final MicroProse project, a licensed Magic: The Gathering game, was released in 1997.

MicroProse’s dual DNA had been there from the beginning, with Stealey’s military instincts, emphasizing realism and immersion, and Meier’s strategic mind, pulling the company toward history and systems. Together, they defined a generation of simulation and strategy games.

Sources: Computer Gaming World, Wikipedia, The New Yorker, Sid Meier’s Memoir!: A Life in Computer Games, Video Game Newsroom Time Machine interview with Bill Stealey, University of Michigan, Retro Gaming Geek, Game Designer Spotlight – Sid Meier, Atarimania, Gamers at Work by Morgan Ramsay, Rom Magazine Issue 3 – Interview with Sid Meier, The Digital Antiquarian…