Last week I wrote about G.I. Joe, one of three titles in Epyx’s “Computer Activity Toys” line. Barbie and Hot Wheels share the same origins and trajectory, and probably should have been part of that story… oh well.

In the late 1970s, with the home computer industry still in its infancy, much of the software being written was aimed at hobbyists and technically minded players. In 1978, Jon Freeman and Jim Connelly founded Automated Simulations, one of the earliest independent computer game publishers. The debut, Starfleet Orion, was essentially a computerized board game, a turn-based space strategy designed to appeal to the same audience that played Avalon Hill war games. The following year, Temple of Apshai introduced role-playing mechanics and dungeon exploration, effectively translating the spirit of Dungeons & Dragons onto the screen. These early titles were intricate and rule-heavy, unapologetically aimed at the intellectually minded, simulation-oriented player.

Early Automated Simulations titles, ranging from 1978 to 1980.

These computer-based strategy and role-playing games helped establish the company as one of the first independent publishers in the home-computer market.

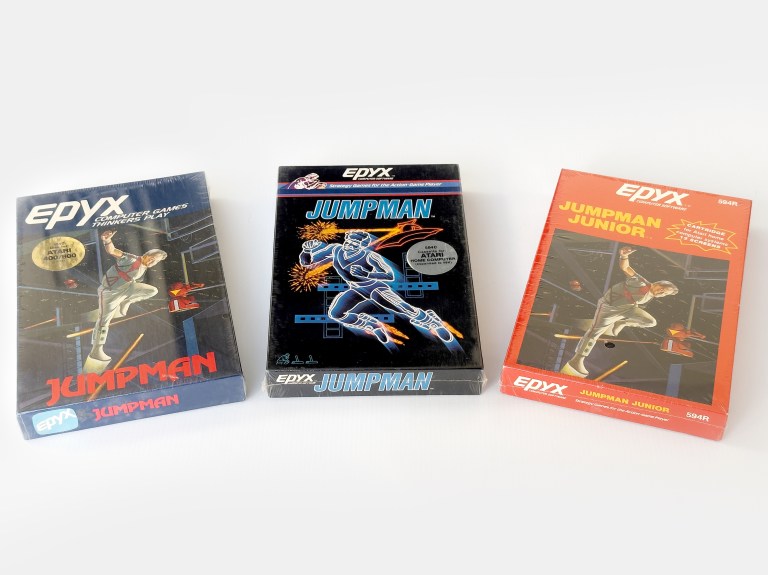

As the industry grew, so did the audience. By 1983, gone were both Freeman and Connelly, and Automated Simulations had rebranded itself as Epyx, a name that sounded sleeker and more in tune with the new arcade generation (the Epyx name had been used since 1980). Where Automated Simulations had been about digital rulesets, Epyx was about energy, color, and fun. The first major hit under the new name came in 1983 with Randy Glover‘s Jumpman, a game that spoke directly to the mainstream with its fast, arcade-style action designed to rival the coin-ops. The company quickly gained a reputation for slick, accessible titles and soon became one of the strong third-party publishers for the Atari 8-bit and Commodore 64, the era’s dominant home computers for gamers. Titles like Summer Games and Impossible Mission were polished, visually impressive, and created with a sense of style that matched the arcade cabinets teenagers flocked to at the mall.

After Epyx’s management change and repositioning in 1983, the company looked to expand beyond its original concepts. Under the guidance of Michael Katz, who had worked in product marketing at Mattel and later served as vice president of marketing at Coleco, Epyx found a new direction. Katz’s impressive resume provided both a working knowledge of retail audiences and an index of industry contacts that would prove decisive.

Randy Glover’s Jumpman from 1983 marked Epyx’s breakthrough into the mainstream.

Moving away from its early simulation roots, the company found success with the fast, colorful platformer, perfectly timed for the arcade-driven home-computer market of the early 1980s.

By the mid-1980s, Barbie was already a household name. Introduced in 1959, Mattel’s Barbie doll had become one of the most recognizable toys in the world, selling in the hundreds of millions and evolving decade by decade to reflect changing fashions, careers, and aspirations. In the 1980s, Barbie’s universe expanded dramatically with not just dolls, but clothing lines, accessories, Dream Houses, cars, records, and a wide variety of merchandise that kept the brand firmly wedged in the public imagination. Barbie was a cultural icon, and for Mattel, the challenge was to keep her relevant in every new medium children embraced.

Hasbro may have captured the boys’ attention with G.I. Joe and Transformers, but Mattel knew Barbie was its perennial powerhouse. Katz, who understood Mattel’s brand strategies from his time there, recognized the potential of bringing Barbie into the booming home computer market. Before leaving Epyx for Atari in 1984, he helped secure licensing agreements not only with Mattel but also with Hasbro.

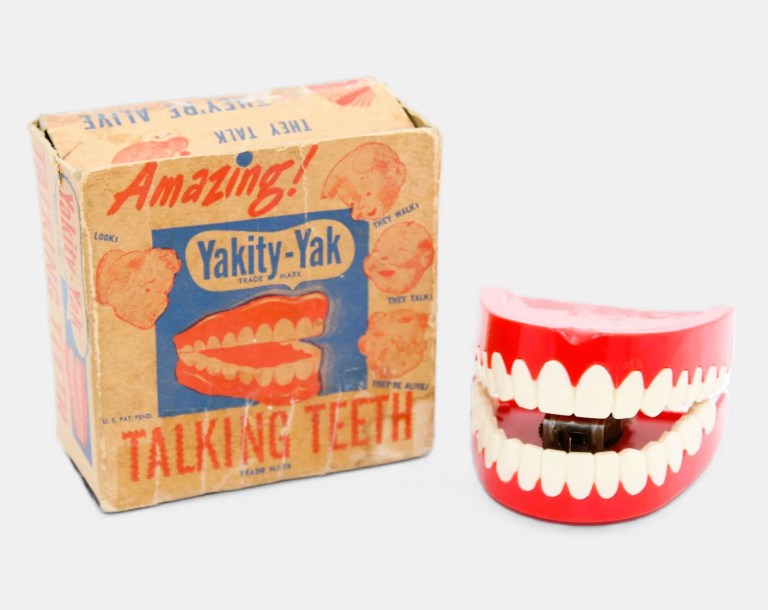

To develop the game, Epyx partnered with A. Eddy Goldfarb & Associates. Eddy Goldfarb was no stranger to toys or children’s entertainment. A prolific inventor whose career began in the late 1940s, he had created or co-created dozens of successful toys, from classics like Yakity Yak Talking Teeth and the Vac-U-Form to electronic gadgets and playsets. During his tenure at Mattel, Katz had already worked with Goldfarb, who was one of the company’s most prominent outside developers. By the 1980s, Goldfarb’s firm had become a go-to design house for translating concepts into tangible products, blending an understanding of play with the technical know-how required for electronic and digital formats. Several of his employees also had programming and game design skills, providing Epyx with the talent and experience needed to adapt Barbie into a computerized universe. For Epyx, having Mattel and Hasbro on board meant instant retail visibility and an audience that extended beyond the traditional computer hobbyist.

Eddy Goldfarb sold his “chattering teeth” design to novelty company H. Fishlove & Co., which released the toy as “Yakity Yak Talking Teeth” in 1949.

Image from smilesfromthepast.com

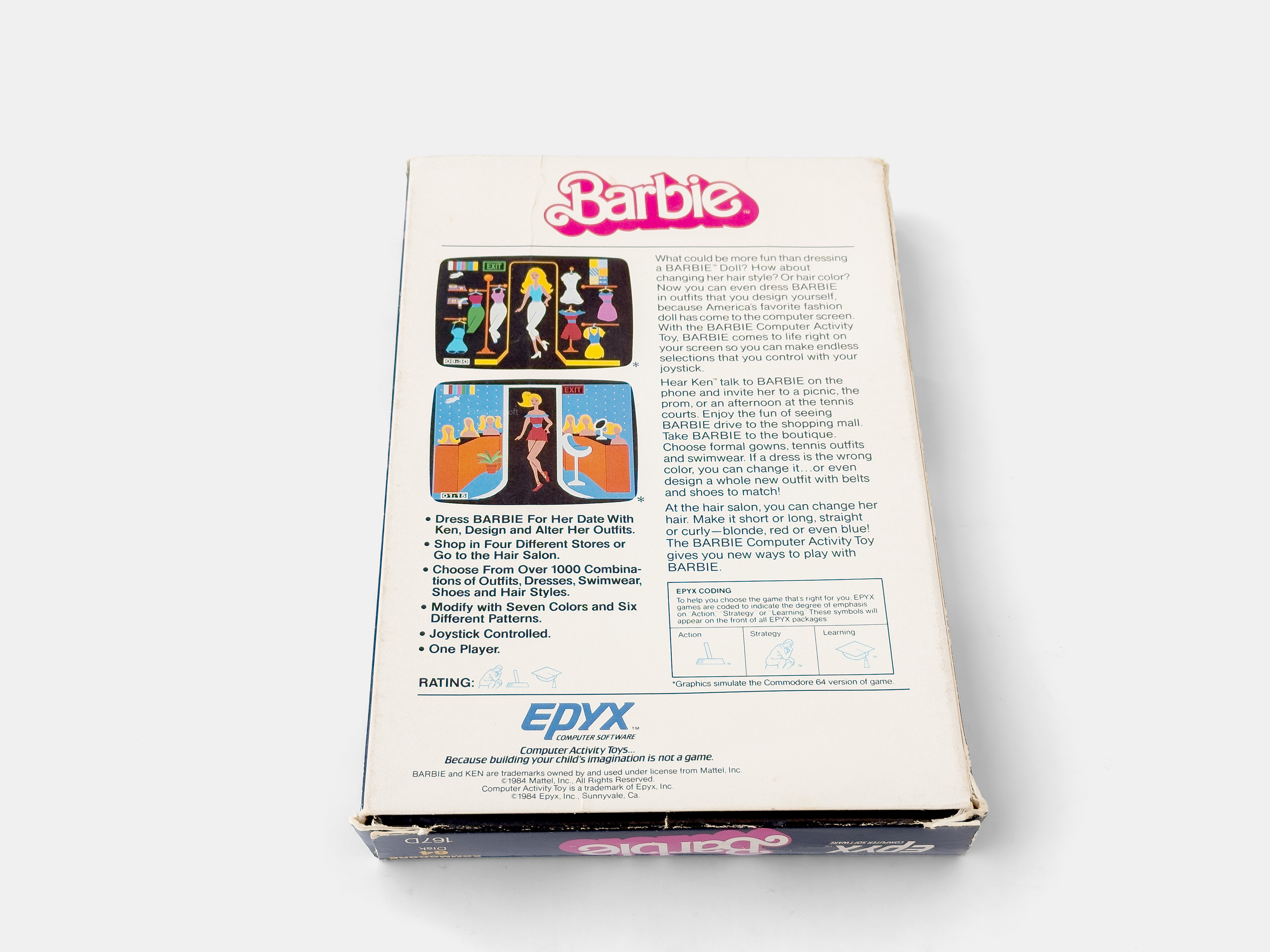

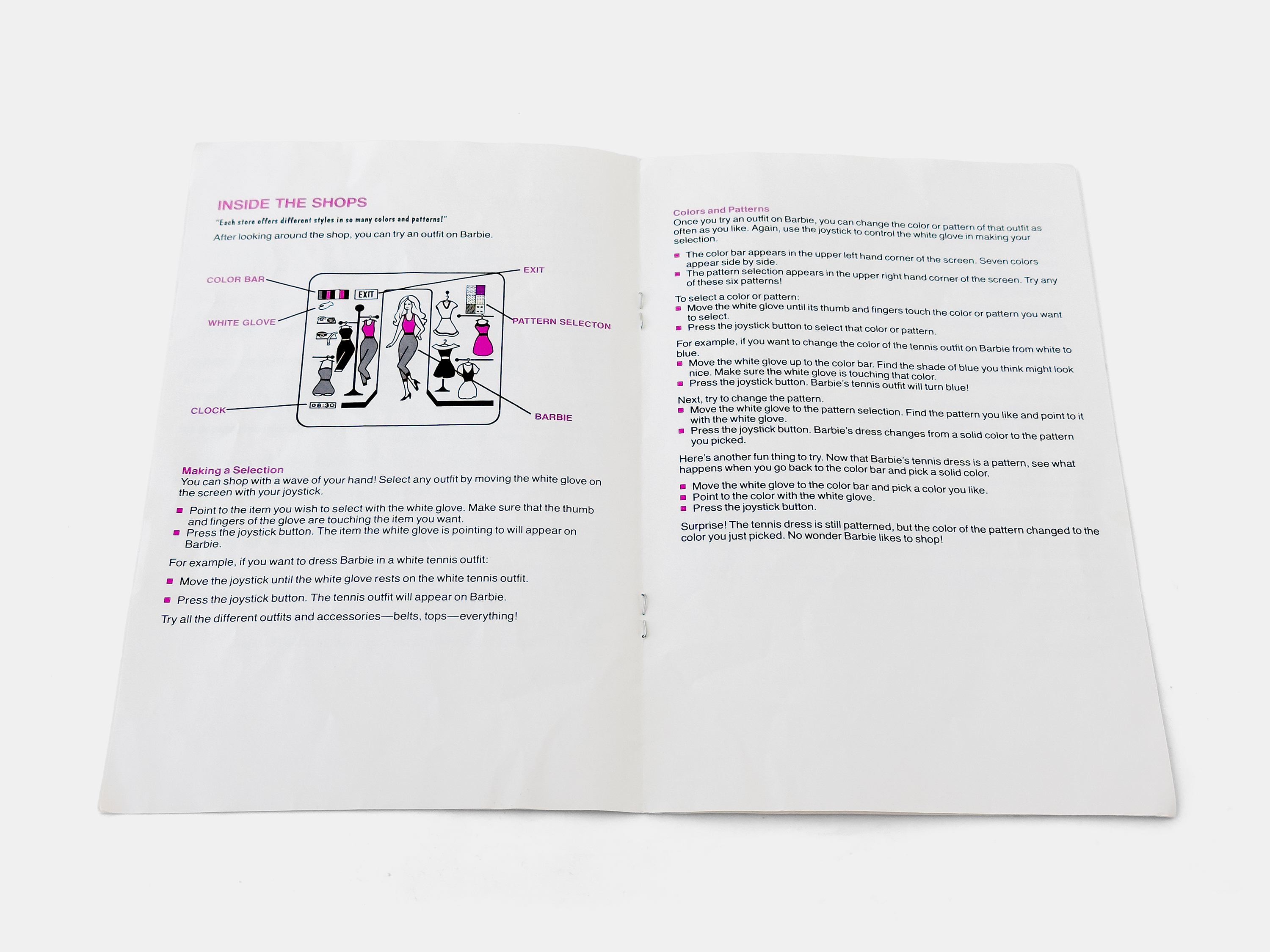

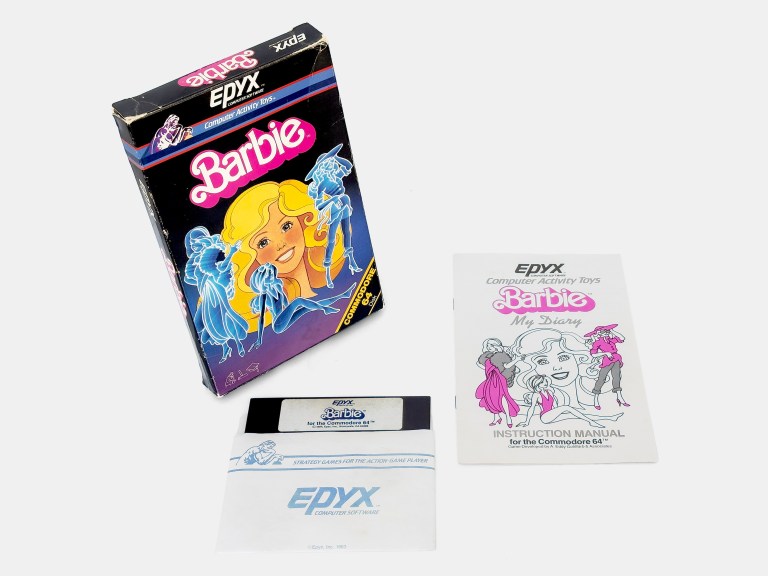

The challenge with Barbie was very different from Epyx’s usual action-heavy fare. Instead of combat or athletic competition, the game needed to capture the fantasy of fashion, social life, and imagination that defined the Barbie brand. This took the form of a simple narrative-driven “activity toy” where players guided Barbie through a day of shopping, fashion choices, and a date with Ken. Instead of points or enemies, the game emphasized exploration, choices, and presentation.

Barbie’s debut on home computers was part of Epyx’s “Computer Activity Toys” line in 1985, alongside Hot Wheels and G.I. Joe: A Real American Hero. Each was aimed at bridging the gap between the physical toys kids already owned and the digital space they were beginning to explore. When the game was first unveiled in June 1984 at Chicago’s Summer Consumer Electronics Show, alongside Hot Wheels, the press reacted enthusiastically to the idea, with coverage appearing in the Chicago Tribune, The News Journal, and The Boston Globe, among other publications. Barbie was released in the spring of 1985, with reviews beginning to appear later in the year. Epyx marketed the Computer Activity Toys titles not as hardcore games but as interactive extensions of play.

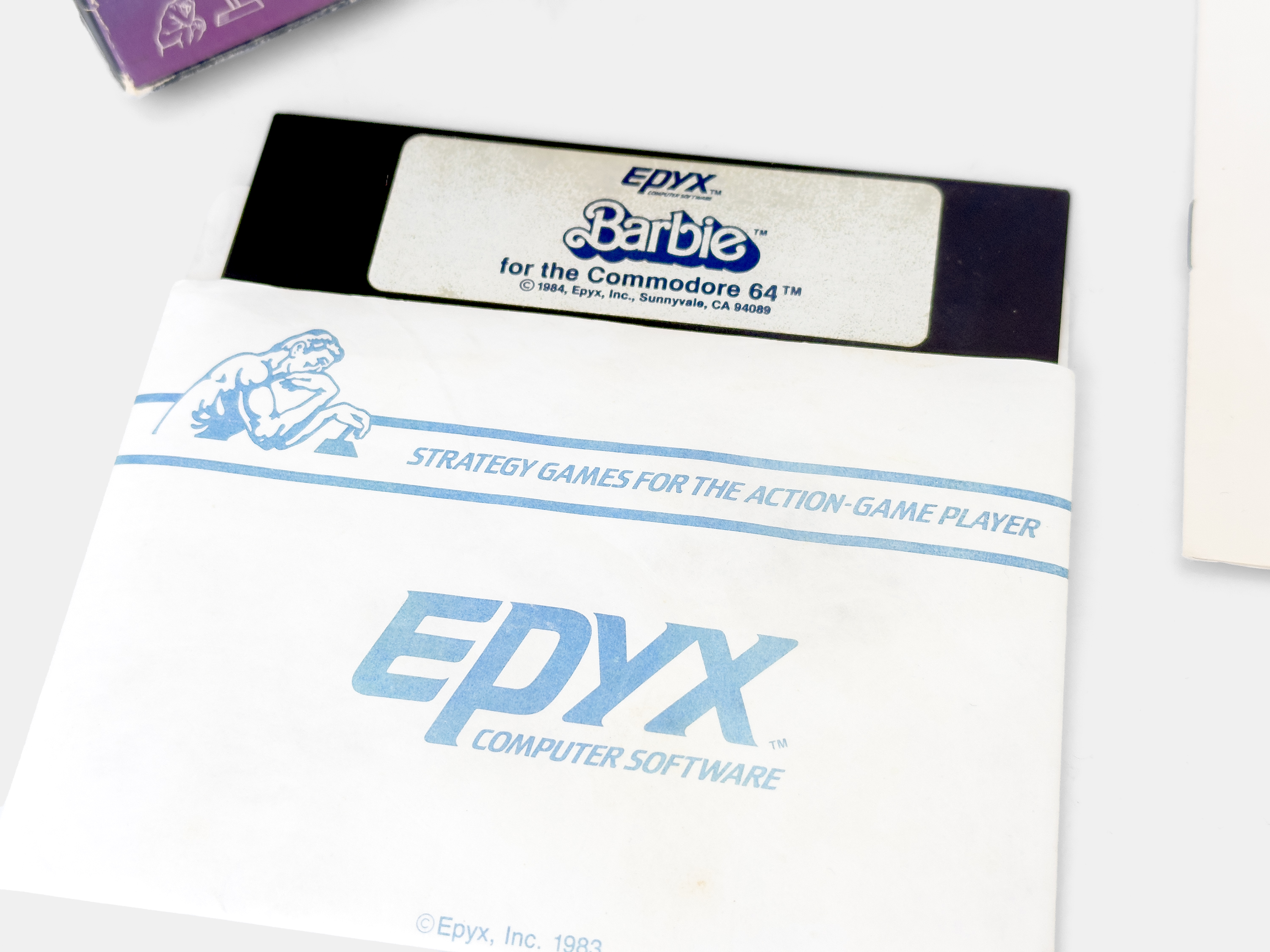

Barbie was developed by A. Eddy Goldfarb & Associates and published for the Commodore 64 by Epyx in the spring of 1985.

Barbie leaned on the Commodore 64’s colorful graphics and SID sound to create a vibrant, cartoon-like environment. Barbie could change outfits, drive her convertible, and interact with Ken, reflecting the aspirational lifestyle promoted by Mattel. The game stood out in 1985 not only for its use of digitized speech, still a novelty at the time, but for its attempt to appeal directly to girls, a market segment largely ignored by the male-dominated computer game industry.

Unlike G.I. Joe, Barbie was not ported to other systems, suggesting that Epyx and Mattel saw the Commodore 64 as the most viable platform for reaching Barbie’s audience, with its large market share. Reviews at the time were mixed. Computer magazines noted the novelty of a Barbie computer game, but critics accustomed to the action and challenge of Epyx’s usual catalog found it lacking in depth. For its target audience, however, Barbie offered something unique.

Barbie wasn’t about pushing technical boundaries, though its digitized speech was a novelty, but about cultural positioning. By the mid-1980s, computer games were beginning to mirror the diversity of the toy aisle. For Epyx, it was an experiment in leveraging one of the world’s most powerful toy brands. For Mattel, it was a first step in bringing Barbie into the digital age. And for A. Eddy Goldfarb & Associates, it marked another inventive turn in a long career of shaping how children played.

Despite the cultural importance, the game struggled commercially and only sold modestly compared to Epyx’s blockbuster sports titles. The company lacked the advertising and marketing muscle to create widespread awareness, and the release received little promotional backing from Mattel or merchandising support from retail giants like Toys R Us, Electronics Boutique, Sears, or Walmart. In the end, Hot Wheels and Barbie would be the final computer games produced by A. Eddy Goldfarb & Associates.

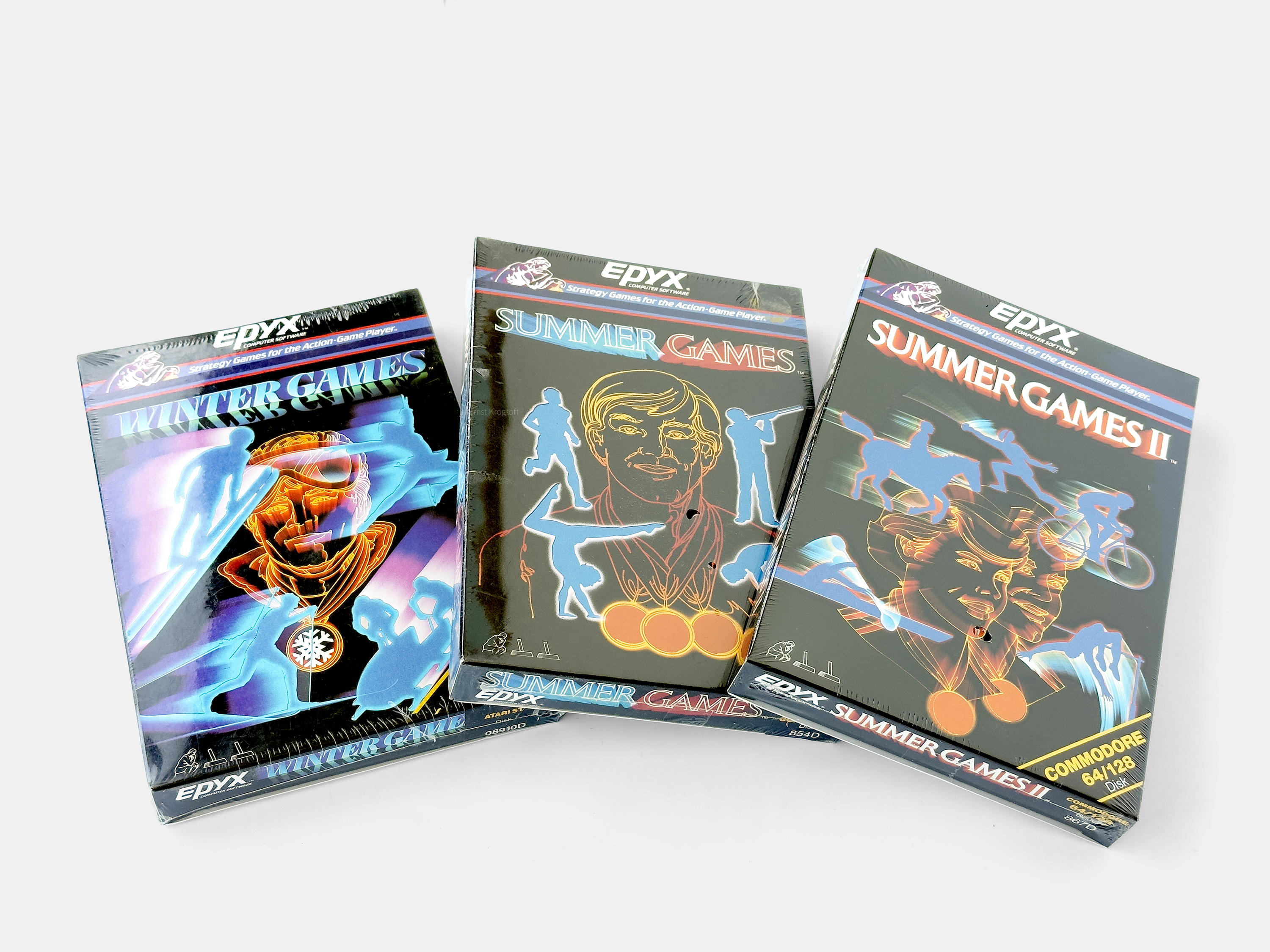

Epyx truly hit its stride in the mid-1980s with its sports simulations. Summer Games and Winter Games became staples of the Commodore 64 and many other systems, remembered as much for their competitive spirit as for the sore hands and broken joysticks they left in their wake.

Barbie marked one of the earliest attempts to design a computer game specifically for girls. Later efforts like Barbie Fashion Designer, from 1996, would make headlines for bringing millions of young women into PC gaming. The title became a phenomenon, selling more than 600,000 copies within its first year and generating $14 million in revenue, outselling heavyweights like Quake and Doom.

Sources: Time Extension, MobyGames, Wikipedia, Edyy’s World…