In the early 1980s, the home computer market was still finding its footing, the rules unwritten, the field wide open to anyone with curiosity, talent, and patience. With a machine like the Apple II, you could write a game, mail it to a publisher, and, if luck and skill aligned, receive royalty checks within weeks. It was the era of bedroom coders, floppy disks in Ziploc bags, and companies that rose and fell almost overnight. Among the dreamers who seized the opportunity was Mark Turmell, a teenager from Bay City, Michigan, who would go on to become one of the most influential arcade designers of the 1990s.

For Turmell, the dream of bedroom coding was no abstraction, and soon it became his teenage reality. Like many of his generation, his path into programming began with curiosity, long hours, and a machine that seemed to promise infinite possibilities. He was drawn to electronics and problem-solving. His father worked in middle management at Chevrolet, while his mother was a homemaker. They hoped he might pursue a traditional career, and law was often mentioned, but Turmell had other ideas.

His high school offered no formal computer courses, but at fifteen, in 1978, he enrolled in evening data-processing classes at Delta College, a hundred miles north of Detroit. A year later, he persuaded his parents to help him buy an Apple II, a $1,400 machine that came with a cassette drive but no monitor. He threw himself into it, working nights and weekends, teaching himself 6502 assembly language by poring over technical manuals and trial and error. BASIC was fine for experiments, but too slow for the kind of arcade action he imagined. He learned how to move sprites, detect collisions, and squeeze every ounce of speed from the 1 MHz machine.

Turmell wanted to make a living from games, and the $1,400 Apple II would soon justify itself. Social life took a backseat. “I was super-shy as a child. I went to college early, at 15 or 16, so I missed out on high-school dates and homecoming. I never went to one high-school dance, and was so focused on computers and this videogame thing, so I missed out on everything,” he admitted years later.

By the time he was finishing high school and starting at Ferris State University, Turmell had already mastered the Apple II’s intricacies. He debugged software for a local engineering firm and consulted on business packages, but what he really wanted to do was design games.

Spending nights and weekends, he created his first full game, Sneakers, a fast-paced shooter clearly inspired by Taito’s Space Invaders. Turmell wasn’t content to mimic the arcade, he wanted to capture its speed and intensity on a home computer. That meant pushing the Apple II beyond, moving multiple sprites smoothly, checking collisions in real time, and keeping the action frantic without bogging down the processor.

Once finished, Turmell faced a choice of shopping his newest creation around locally or aiming higher. He had been reading about Sirius Software, a fast-growing publisher out in California that seemed to be everywhere in the Apple II world. The company was building a reputation for discovering young, unknown programmers and giving their games national exposure.

Founded in 1980 in Sacramento by Jerry Jewell and Terry Bradley, Sirius had published dozens of titles, many of them arcade-inspired hits, and was generating millions in revenue. For a teenager in Michigan, Sirius looked like the quickest path from bedroom coder to professional game designer.

Turmell packed Sneakers and shipped it west. Jewell and his team were immediately struck by the game’s polish and energy, and quickly signed it. Practically overnight, Turmell went from a high school student learning assembly in his bedroom to a published author with royalty checks worth thousands arriving in the mail. His name appeared in the press, and for the first time, the idea of making a living from games no longer seemed like a far-fetched fantasy.

When Sneakers was released in mid-1981, the Apple II library was still dominated by text adventures, role-playing games, and educational programs. Turmell’s creation stood out as pure arcade action, with the frantic speed reminiscent of Sirius Software’s other hits, many by Nasir Gebelli, a programmer whose code, at the time, seemed to bend the Apple II beyond its limits.

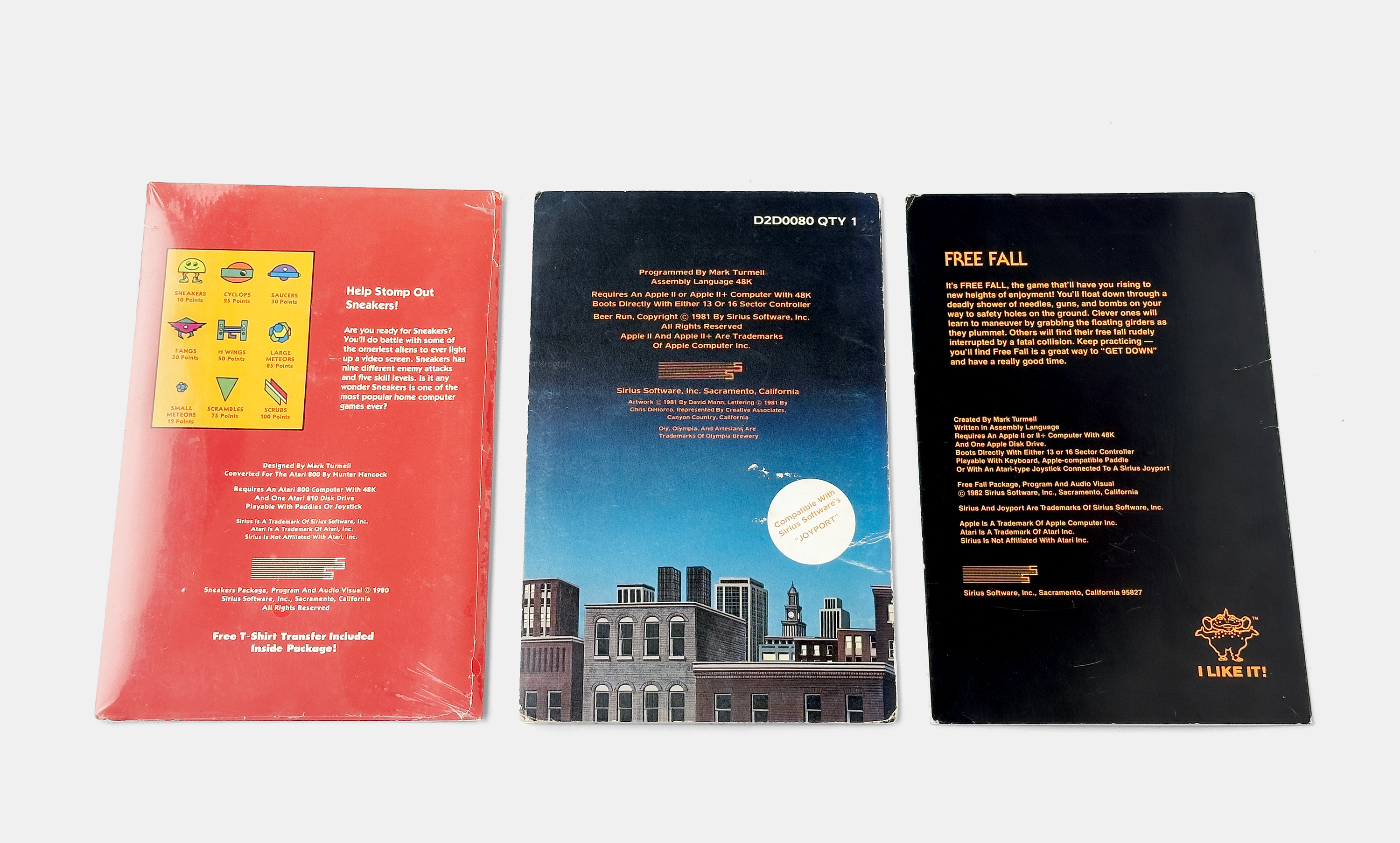

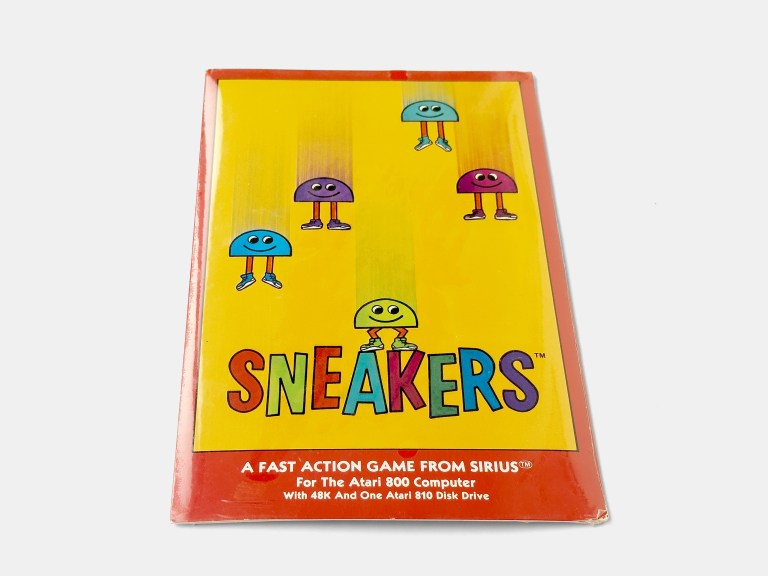

Mark Turmell’s first game, Sneakers, was picked up by Sirius Software and published in July of 1981.

Its strong Apple II sales carried it into Softalk’s “Top Thirty” chart and prompted Sirius to commission a port for the Atari 800, handled by Hunter Hancock (shown here).

Sneakers moved quickly, responded crisply, and captured the spirit of the coin-op arcade games that teenagers were lining up for at the mall. For Apple II owners, that kind of immediacy was rare. Players have to defend against incoming waves of enemies, each with distinct patterns and behaviors. One group, the “Scrubs,” could be hit twice, once to knock them down and again for bonus points while they tumbled. The playful detail gave the game humor and personality, helping it stand out in reviews and sales charts.

Sneakers was received with critical acclaim. Softline praised its graphics and addictive qualities, while the Arkie Awards honored it with a Certificate of Merit for “Most Humorous Home Arcade Game.” The combination of fast action and playful touches gave the game a distinct personality in a marketplace crowded with more straightforward shooters.

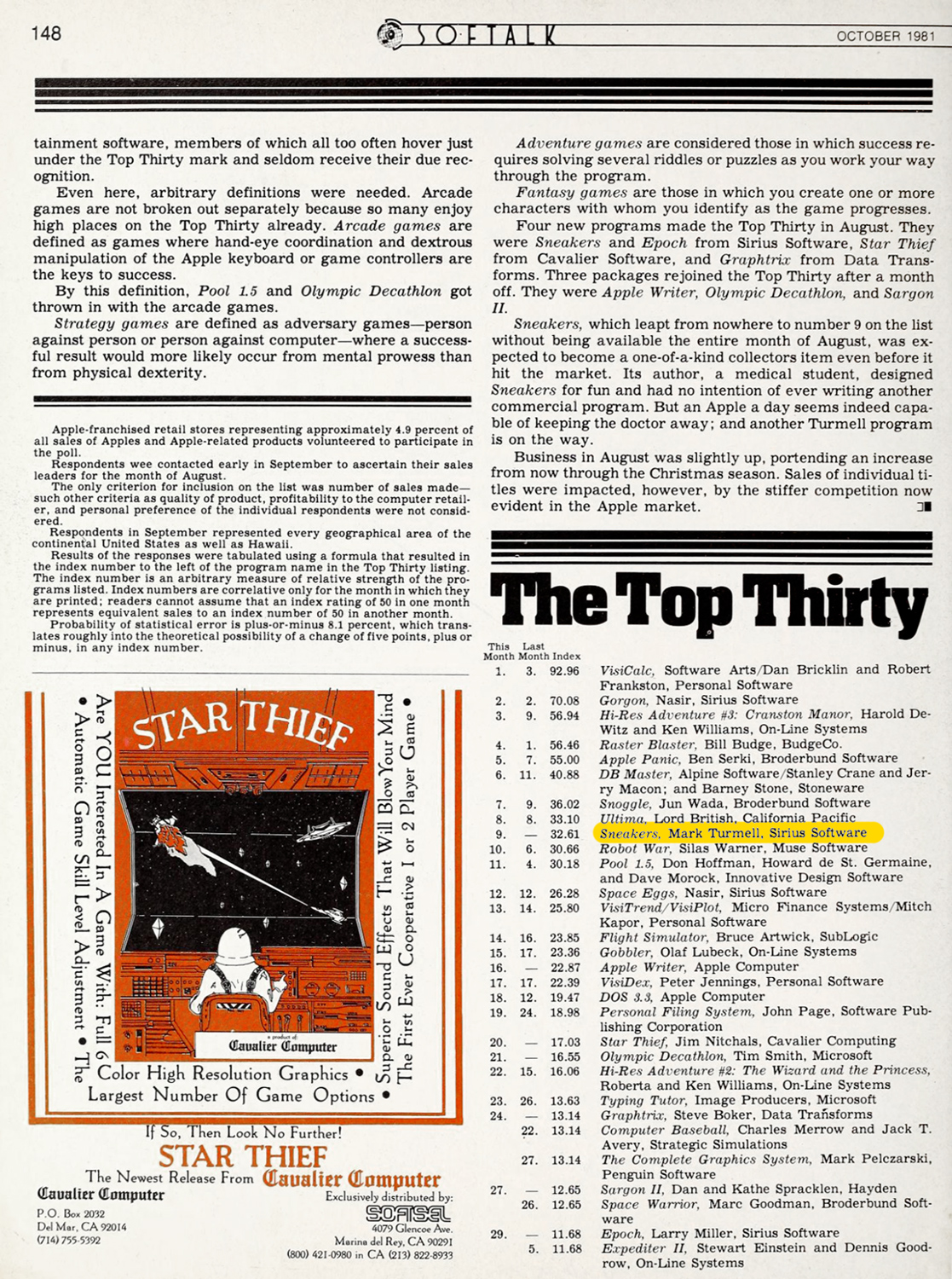

Within its first two months, Sneakers sold around 10,000 copies, a remarkable figure for the time. By October, it reached ninth place on Softalk magazine’s “Top Thirty” list, which tracked actual sales reported by retailers.

Sneakers went straight into 9th place on Softalk’s “Top Thirty” in October 1981, a monthly chart based on sales figures reported by Apple II retailers across the United States.

In a later interview with Electronic Fun with Computer & Games, Turmell explained that getting Sneakers to run cleanly on the Apple II had been a painstaking process of refinement, wrestling with memory limits, mitigating sprite flicker, and constantly balancing speed against graphical detail. “Balancing the levels so they weren’t too boring but not impossibly hard,” he recalled, was as important as the code itself.

Turmell’s focus came at a personal cost, but it gave him an extraordinary head start. He moved to California when he was around 19, a leap he made soon after Sneakers sold and Sirius signed the title. Yet while he missed out on much of the teenage social life other teenagers took for granted, his game was giving him opportunities most could only dream of. The move put him in the heart of the fast-growing software scene. Sirius’s offices were close by, and California was filled with other young programmers chasing the same dream.

The success of Sneakers brought Turmell something almost unheard of for a teenager in the early 1980s: real money. Royalty checks for thousands of dollars began arriving in the mail. For a kid who had once pooled together lawn-mowing money and a parental loan to buy his first Apple II, the sudden financial freedom was exhilarating. His first big-ticket purchase was a Porsche 924 Turbo, loaded with options, a high-end stereo, and a new bike. Practically overnight, Turmell had become a symbol of what young programmers could achieve in the early home-computer era.

One of Sneakers’ fans was none other than Apple co-founder Steve Wozniak. After a small plane crash left him hospitalized, he spent hours playing Turmell’s creation. “So I got this invitation to attend Wozniak’s wedding,” Turmell later remembered. “I was thinking, ‘Why was I invited?’ And he comes up to me and explains that while he was in the hospital, Sneakers was the game he played over and over.” He wanted to invite people who were making the Apple community vibrant.

The success of Sneakers gave Turmell freedom to experiment. His follow-up, Beer Run, could not have been more different. Inspired by Olympia Beer’s 1981 commercial celebrating the “artesian well water” used in its brewing, and its cartoonish mascot, the Artesian Hillbilly, Turmell created a game where players climbed a multi-story building while trying to collect falling beer cans.

The gameplay owed more to Donkey Kong than Space Invaders, with ladders, obstacles, and hazards replacing rows of alien creepers and ships. It was lighthearted, even goofy, and showed Turmell testing the waters of platform design.

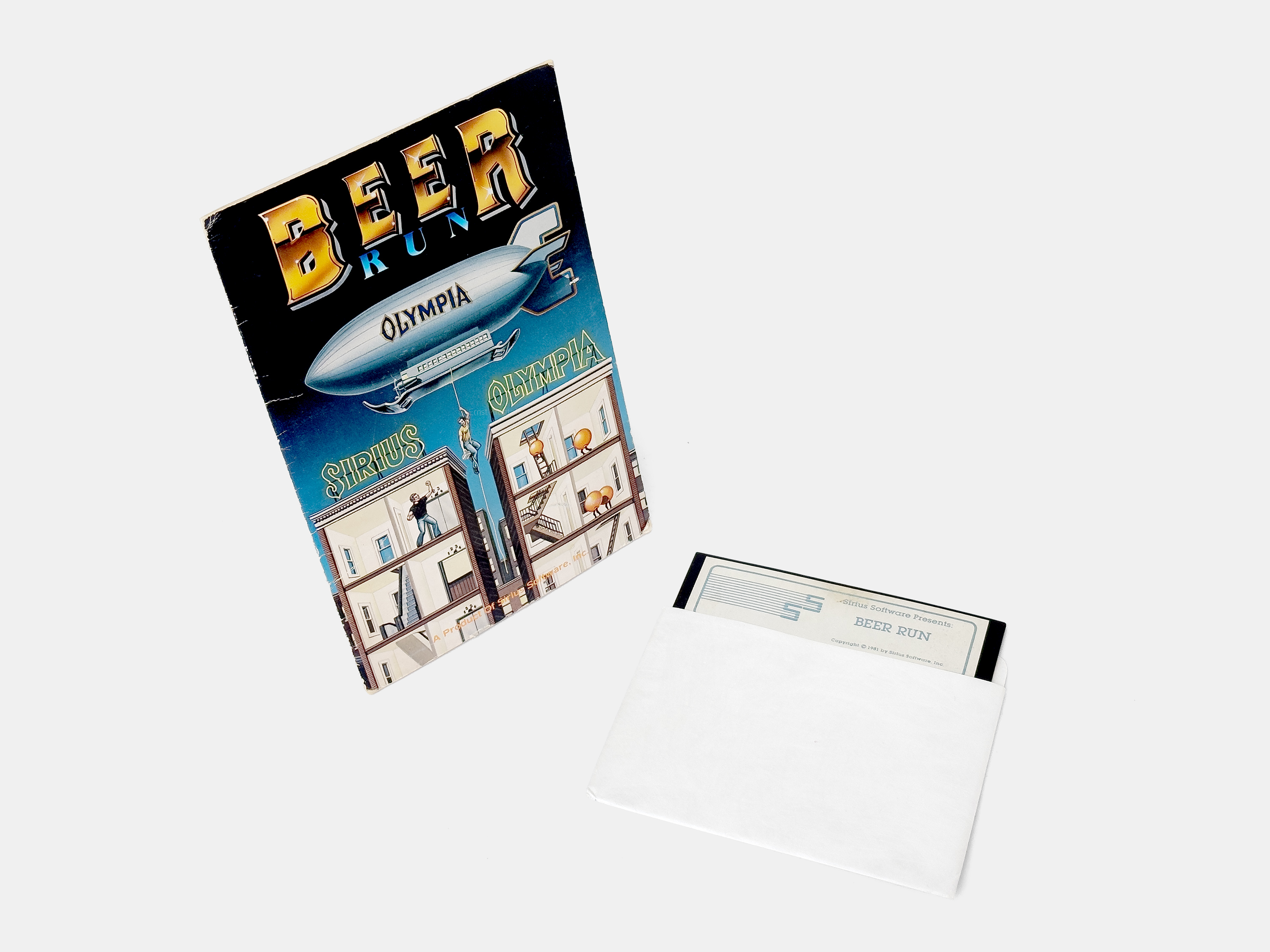

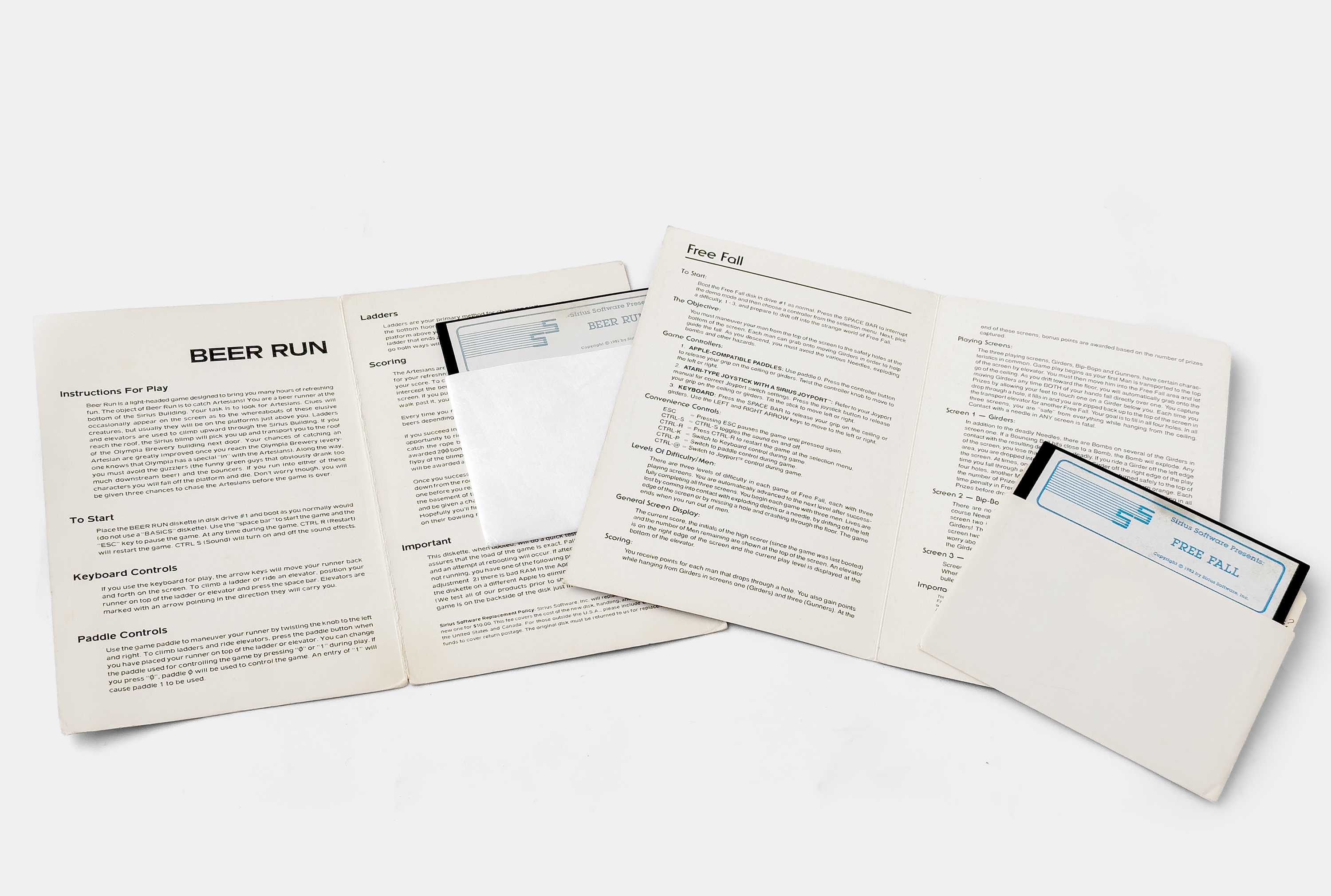

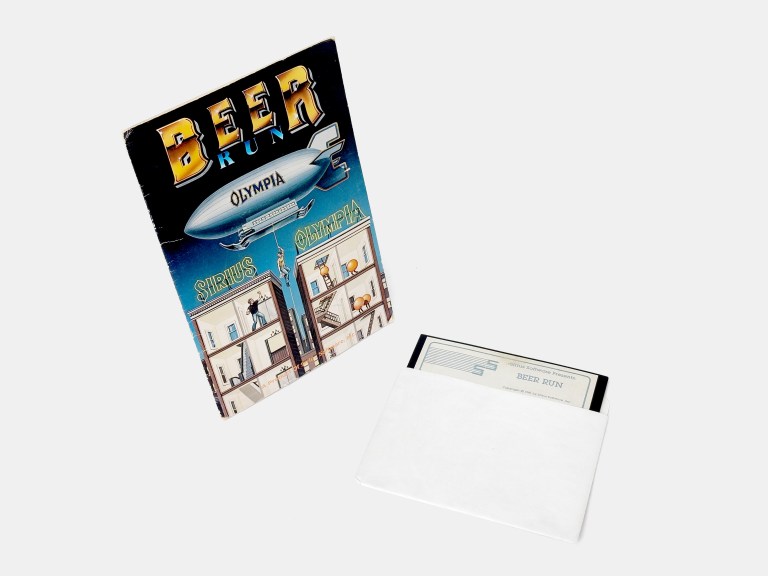

Turmell’s second game, Beer Run, was another Sirius Software release. published in the latter part of 1981.

It never matched the chart success of Sneakers and, due to its comparatively low sales, was never ported to other systems.

Beer Run challenged players with ladders, elevators, and roaming enemies, all while navigating a lighthearted premise: catching beer cans tossed by mischievous sprites. A Donkey Kong–style climb-and-dodge game, it moved beyond shooters and showcased Turmell’s early experimentation with platform mechanics and playful themes. Despite its inventiveness, the game remained a modest seller and was never ported to other systems.

Beer Run showed Turmell experimenting beyond shooters, trying his hand at a platform-style game with vertical movement and environmental hazards. It was inventive, but inevitably, compared to Sneakers, it felt like a sophomore effort. Reviews noted its novelty but judged it less compelling than his debut. It only sold around 2,000 copies and never reached the Softalk charts, but it reinforced Turmell’s reputation as a designer willing to take risks rather than repeat himself.

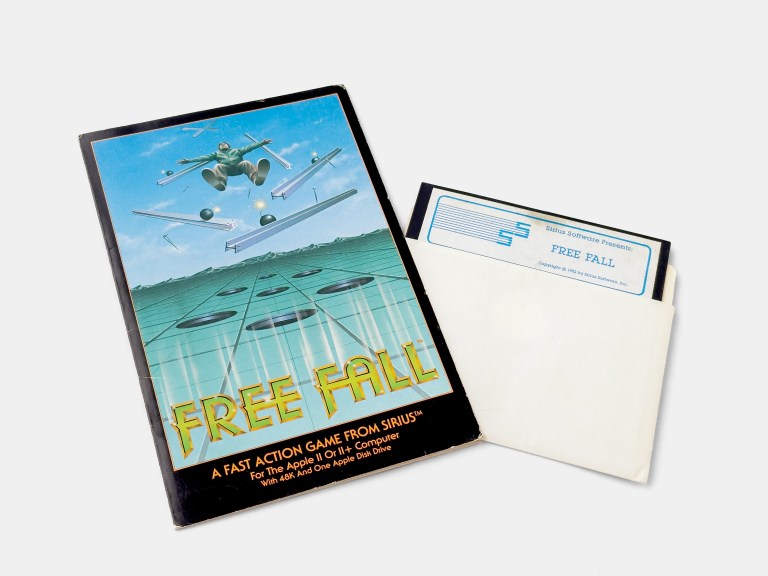

Turmell’s third Sirius title, Free Fall, arrived the following year, in 1982. Once again, it explored different mechanics. Players guided a character tumbling through a vertical shaft, dodging hazards on the way down. The concept was simple but quirky, built around timing, reflexes, and a playful tone.

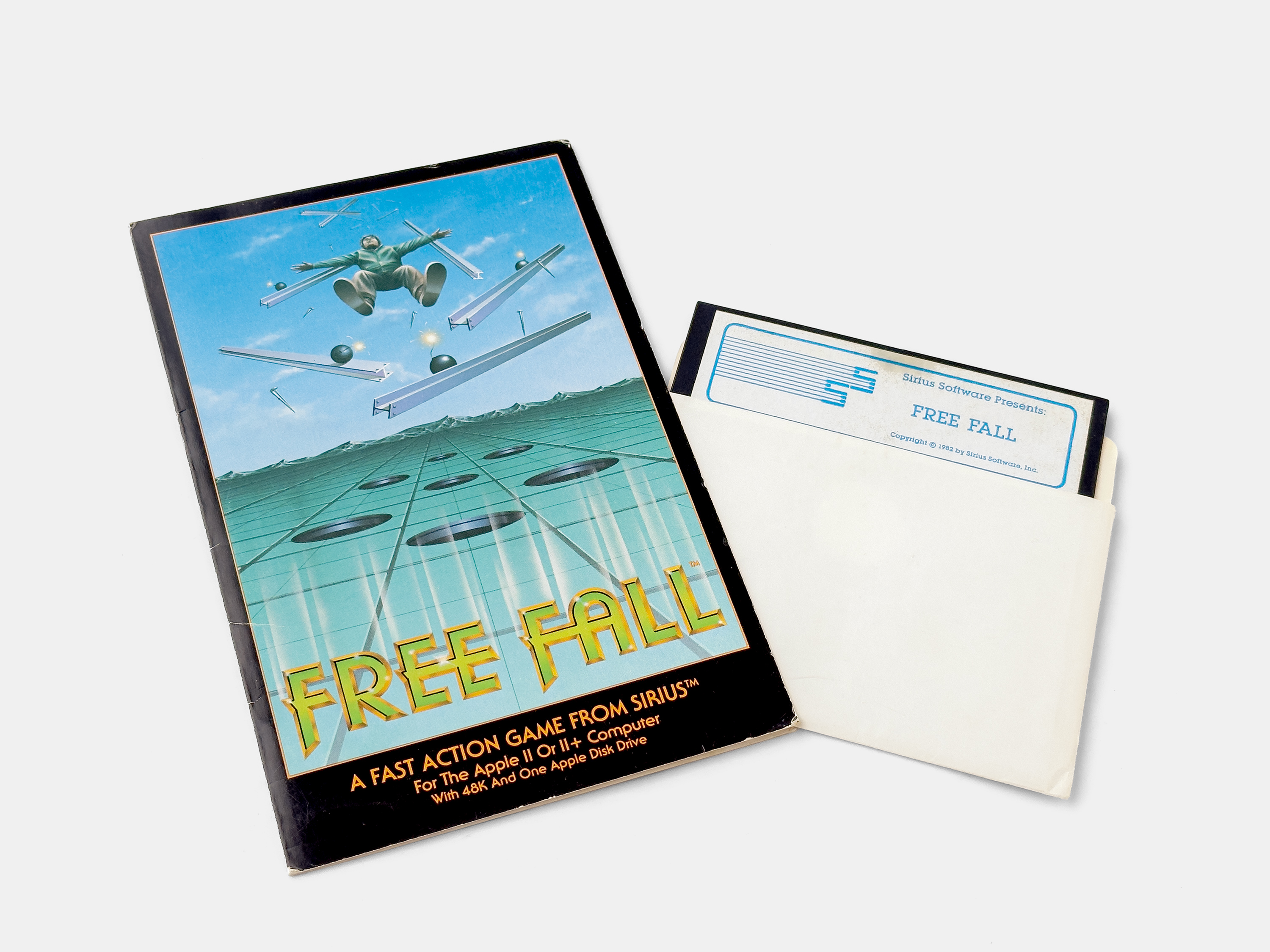

Free Fall, released by Sirius Software in 1982, was Turmell’s third and final Apple II title.

Like Beer Run, it failed to reach the sales charts and remained an Apple II exclusive.

With Free Fall, Turmell once again experimented, this time creating a quirky action game with lighthearted mechanics. Magazines like Electronic Games praised its originality, though it remained a modest seller, overshadowed by his debut hit. Players controlled a character suspended at the top of the screen, who had to release and fall safely through a maze of moving girders, bombs, and bouncing hazards. Success relied on timing the drop and steering mid-air to slip through holes at the bottom.

Electronic Games magazine described Free Fall as lighthearted and unusual, but like Beer Run, it failed to replicate the runaway success of Sneakers. Sales were modest, and it never broke into the Softalk charts. Still, for Turmell, each project was a stepping stone. “Both Beer Run and Free Fall were experiments,” he reflected. “I was more interested in trying new things than chasing the exact same success.”

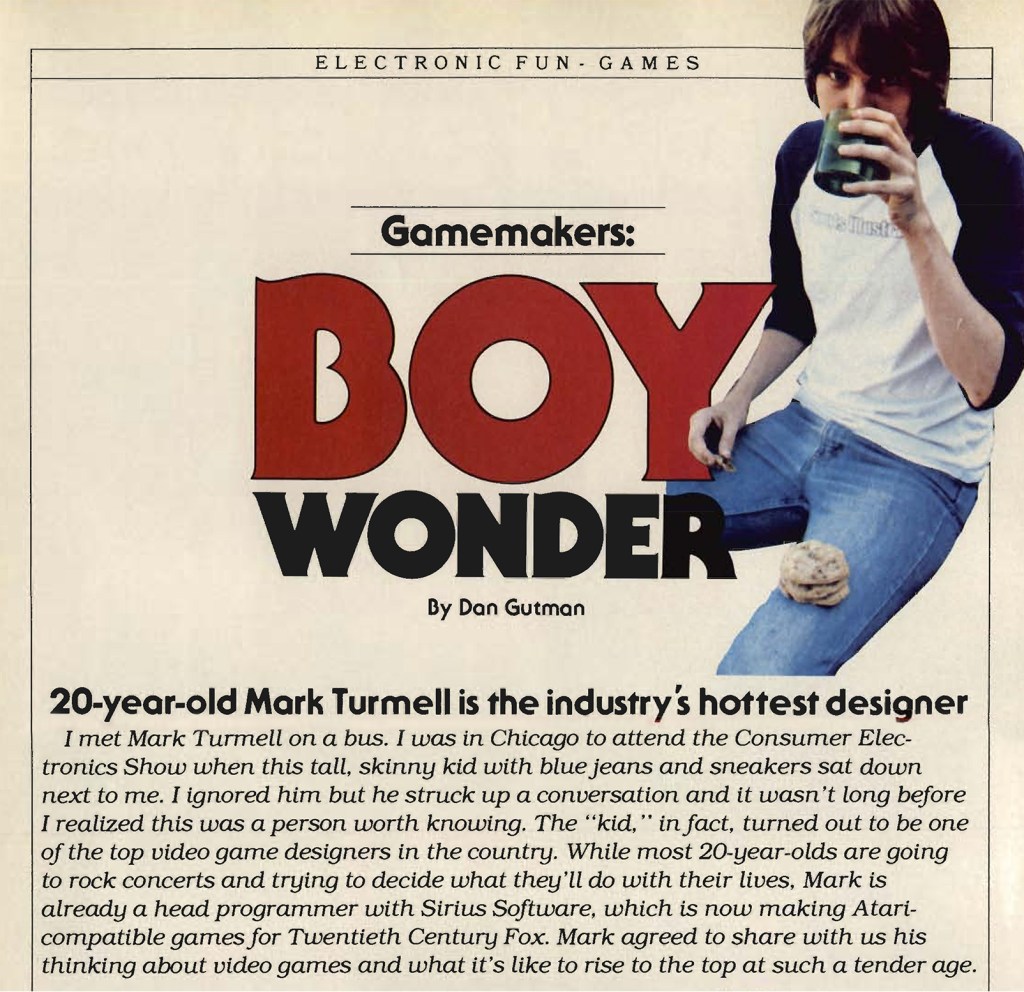

The November 1982 launch issue of Electronic Fun with Computer & Games carried a five-page interview with Mark Turmell by Dan Gutman. With a reported print run of 250,000 copies, likely a promotional figure, the feature brought Turmell wider recognition and served as encouragement for young aspiring programmers and game designers.

By the time Free Fall was released, the golden window for Apple II bedroom coders was closing. The North American video game crash of 1983 devastated publishers like Sirius, which folded that same year. The industry was shifting from solo hobbyists to professional teams, from floppies in baggies to multimillion-dollar productions.

For Turmell, barely out of his teens, this was less a setback than an opening. His three Apple II games had given him visibility and credibility, and soon he was working on Atari 2600 titles like Fast Eddie and Turmoil for Sirius before it folded. He joined Williams Electronics in the late ’80s and created original hits. At Midway, he became the name behind multimillion-selling titles like Smash TV, NBA Jam, NFL Blitz, NBA Showtime, WWF WrestleMania, and NBA Ballers.

The culmination of his journey came with NBA Jam in 1993. Combining lightning-fast basketball action with outrageous dunks, digitized player likenesses, and memorable catchphrases, it became one of the best-selling arcade games of all time. The kid who once mailed a floppy disk to Sirius Software had become one of the defining figures of the arcade boom of the 1990s, with titles that together generated over a billion dollars in arcade revenue.

Mark Turmell, pictured in 1993, the same year his NBA Jam, one of the best-selling and highest-grossing arcade games of all time, was released.

Image from Detroit Free Press.

Later, as senior creative director at Electronic Arts, Turmell helped refine the Madden franchise and spearheaded the rebirth of NFL Blitz. In 2011, he moved to Zynga as part of the social gaming wave.

Sources: The Golden Arcade Historian, Wikipedia, MobyGames, Electronic Games magazine, Softalk Magazine, Killscreen Interview with Mark Turmell, Softline interview by Greg Voss, Electronic Fun Computer Games Vol. 1, 1982 interview with Mark Trumell, Retromags, Detroit Free Press…

I met Mark when I was flown out to California to submit a game I wrote as well as another friend. He was very nice and Jerry Jewel and the crew where very inviting even though they turned our games down. I also met him again at a gaming tournament in Las Vegas that was created as a publicity stunt to sell our titles. We each had to play each others games. Softalk magazine did a story on it, I had found it and scanned it and sent it to Mark years later. He was flabbergasted he had forgotten all about it. You can see it here with a picture of Mark in the lower right hand corner. http://www.btstream.com/pietro/wizvswiz.html

Peter, thanks for sharing, that was great.