In the early 1990s, the games industry found itself on the edge of a revolution. For more than a decade, developers had battled against the limited capacities of floppy disks. Graphics, audio, and every line of code had to be squeezed, trimmed, and compressed until barely fitting into a handful of megabytes. With the arrival of the CD-ROM, new possibilities were unlocked, enabling full voice acting, orchestral soundtracks, full-motion video, sprawling worlds, and cinematic storytelling. For the first time, games were able to look, sound, and feel like the movies they had aspired to match.

The shift had been building since the late 1980s. Even before CDs were widespread, companies were regarding “multimedia” as the future. Philips had launched the CD-i in 1990, Sega was readying its Sega CD add-on, and computer manufacturers like Packard Bell were bundling CD-ROM drives with their machines, promising interactive encyclopedias, talking storybooks, and, most enticingly, games of unprecedented magnitude.

The term “multimedia” wasn’t just a buzzword. It reflected a genuine shift in how games were made, and full-motion video, FMV, was to be the golden ticket. Games quickly flooded the market. Night Trap promised B-movie horror. The 7th Guest terrified players with eerie puzzles and lavish pre-rendered backdrops. Wing Commander III boasted Hollywood talent like Mark Hamill and Malcolm McDowell. Sierra’s Phantasmagoria grabbed headlines for its shocking content and million-dollar budget. The FMV craze had momentum, and for a few short years, it seemed unstoppable.

In France, one studio was already preparing to seize the moment. Paris-based Cryo Interactive had its roots in the mid-1980s, when programmer Rémi Herbulot and designer Philippe Ulrich were creating games at ERE Informatique, one of the country’s most inventive software houses. When Infogrames absorbed ERE in 1987, many of its most creative minds resisted being folded into a corporate machine. Among them were Herbulot and Ulrich, who soon found a partner in Jean-Martial Lefranc, a graduate of Sciences Po Paris, the country’s leading political science institute. With experience in French television and as head of development at Virgin France, where he helped launch SEGA in the local market, Lefranc brought a sharp business sense and a deep understanding of media production. That influence would prove vital as Cryo pushed into the emerging world of full-motion video and cinematic presentation. Together, the trio founded Exxos, an experimental label that blurred the line between commercial studio and digital art collective. From Exxos grew Cryo Interactive, officially established in 1990, carrying forward the same philosophy of technical ingenuity married with an atmospheric cinematic flair. The breakthrough came in 1992 with Dune. Part adventure game, part strategy title, it amazed players with its expansive visuals, its emotive soundtrack by Stéphane Picq, and its ability to capture the essence of Frank Herbert’s desolated world. The game not only put Cryo on the map, it gave the company leverage when pitching future projects in the emerging multimedia space.

With that success and new financial backing, Cryo aimed higher, and their next project, MegaRace, would dive headfirst into the multimedia boom. On paper, it was a futuristic combat racer. In practice, it was something stranger: a satirical TV broadcast from a dystopian future, with the player cast as a contestant in a deadly racing game show.

At the center of it all was Lance Boyle, an over-the-top host portrayed by American actor Christian Erickson. Filmed in Paris, Erickson’s performance was a blend of manic energy, sleazy charm, and fourth-wall-breaking banter. Much of his dialogue was loosely scripted, and Erickson improvised heavily on set, giving the character a manic unpredictability. His face, his voice, and his taunts would be the connective tissue that held the whole experience together.

Wrapped around Boyle’s theatrics was the racing itself. Real-time 3D graphics weren’t ready. Early 3D hardware was still years away, and the 486 DOS-era PCs simply couldn’t push fast-moving polygons at the fidelity Cryo wanted. The solution was interesting. Every race track was created in Autodesk 3D Studio, then rendered out and compressed into looping FMV sequences using the Cinepak codec, an early standard for CD-ROM video that allowed playback from even single-speed CD-ROM drives. The game would play back the prerendered backgrounds with the player’s car, rendered as a 2D sprite on top. Enemy cars and explosions were handled the same way. It was a clever workaround, and while it limited player freedom, it ensured MegaRace looked slicker than any contemporary computer could have rendered in real time.

Once development had taken shape, Cryo needed strong publishing partners who could push MegaRace into the growing CD-ROM market. In Europe, the role was filled by Mindscape, a company already well established in distributing both educational titles and games across the continent. For North America, Cryo turned to The Software Toolworks, a California-based publisher that had rapidly expanded from its roots in educational software. After scoring major successes with The Chessmaster series and Mario Teaches Typing, Toolworks was eager to prove itself in the booming multimedia market, aggressively acquiring and publishing titles that showcased the capabilities of the CD-ROM. Both companies recognized the appeal of MegaRace not just as a game, but as a technical showpiece, flashy video, digitized sound, and a presentation that felt ahead of its time.

MegaRace was released for MS-DOS in the spring of 1993. Riding the wave of the early CD-ROM boom, it was positioned as both a technical showcase and a piece of entertainment that felt radically different from anything on floppy disks. For many PC players, it was among the first titles that truly justified the purchase of a CD-ROM drive.

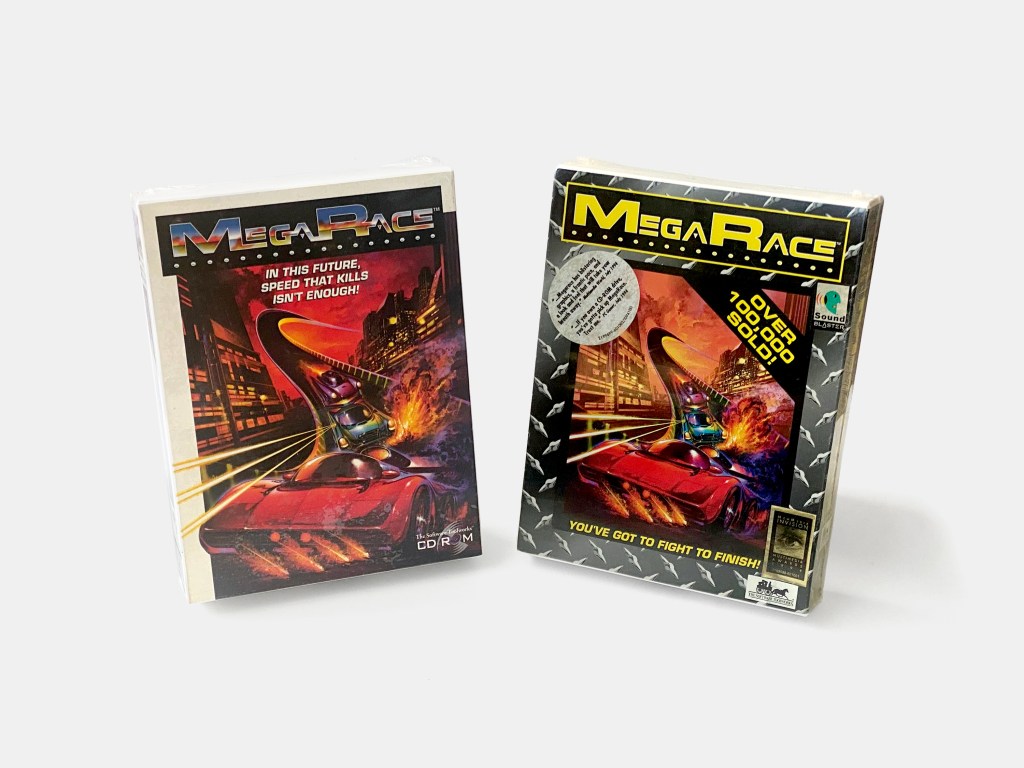

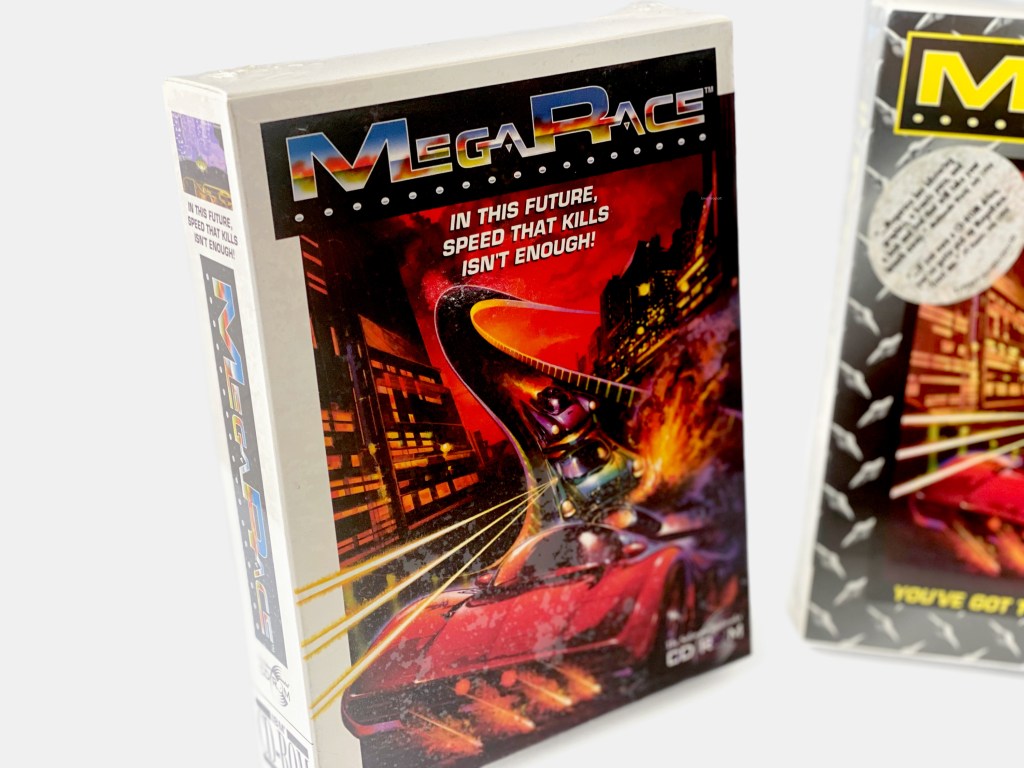

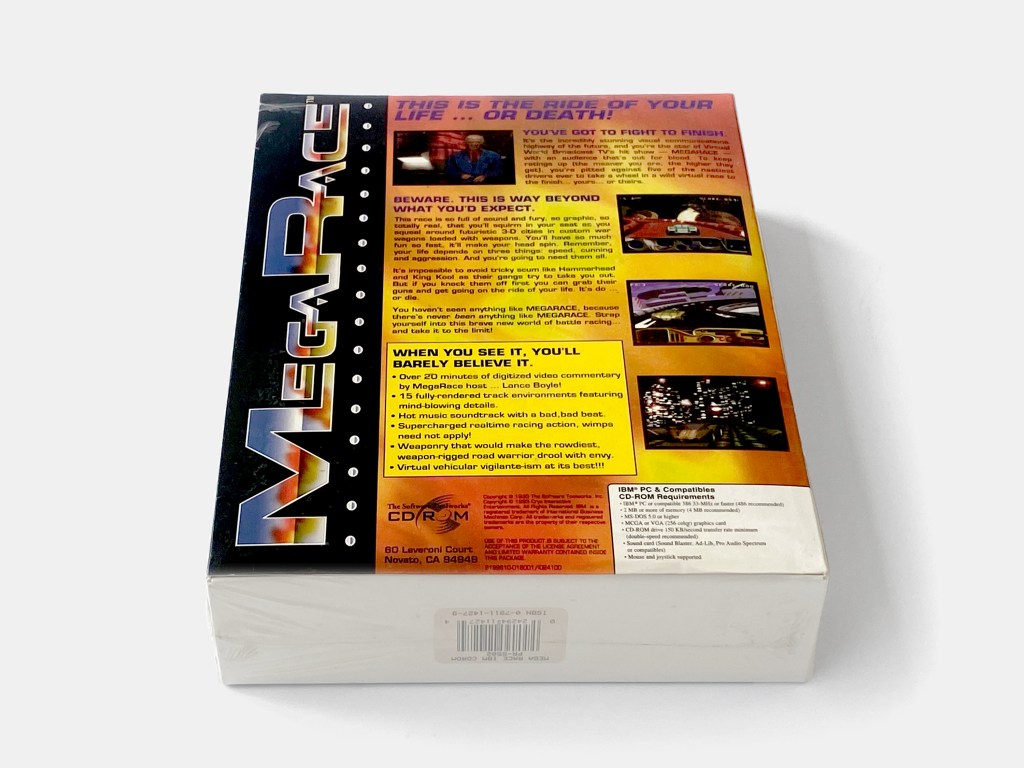

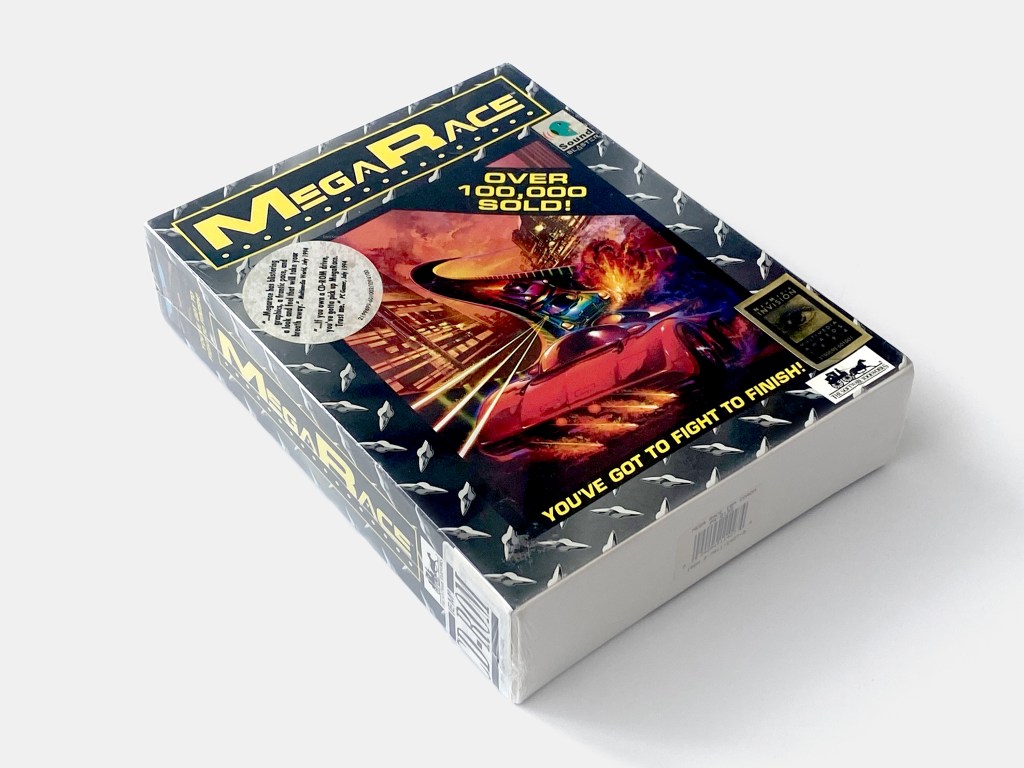

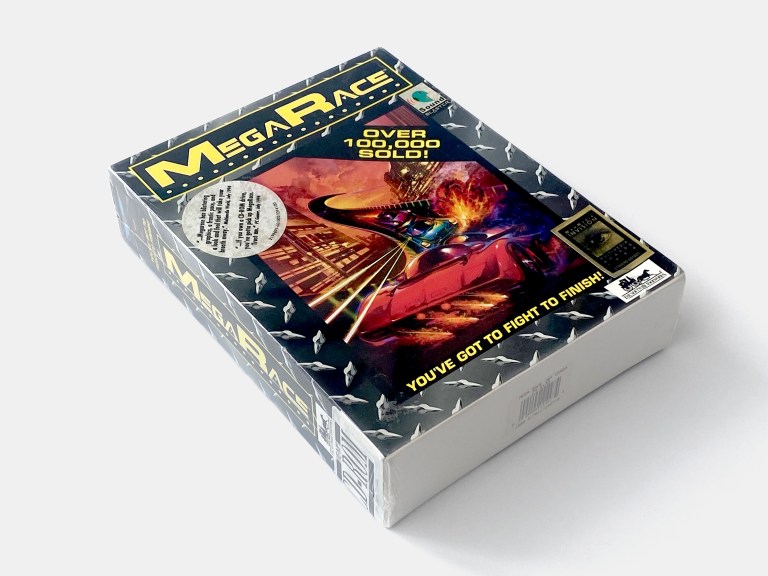

Cryo Interactive’s MegaRace was published in North America by The Software Toolworks in the spring of 1993.

The game was every bit as excessive as its title promised.

MegaRace blends futuristic combat racing with full-motion video trickery. Players speed through pre-rendered 3D tracks, steering a 2D car sprite while battling enemy drivers in a deadly TV game show setting. Guided and constantly mocked by over-the-top host Lance Boyle.

Former staff have recalled that even for MegaRace, designers sketched mock “broadcast schedules” and Lance Boyle catchphrases long before the racing mechanics were finished, showing how central the parody TV-show framing was. In some ways, the races were the filler between commercials and Boyle’s banter.

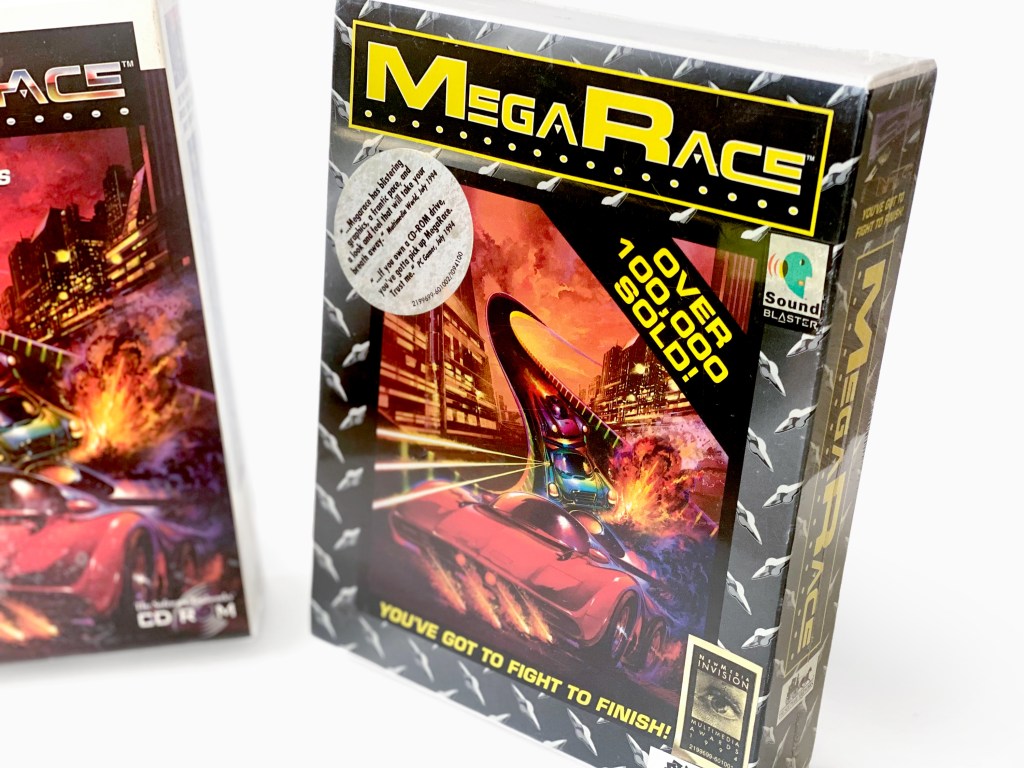

The first retail box carried Toolworks’ standard branding, but a year later it returned in a black “Best Seller Series” reprint boasting a “100,000 copies sold” sticker, reflecting the publisher’s new budget-line push. Its reach expanded dramatically when Packard Bell, the same year, began bundling it with its home PCs, a practice that continued through 1997. Packard Bell’s own marketing campaigns often listed MegaRace alongside Microsoft Encarta as proof of what a CD-ROM drive could deliver, a futuristic racer and a digital encyclopedia pitched together as the “killer apps” of the new format. For countless households, MegaRace wasn’t a game they sought out in stores; it was their very first CD-ROM experience, delivered straight out of the box by Packard Bell.

The Software Toolworks rereleased MegaRace in 1994, aiming to highlight strong sales and to renew consumer interest.

Following its PC debut, Cryo adapted MegaRace to other CD-based platforms. In 1994, it appeared on the Sega CD and Panasonic‘s 3DO, two systems that leaned heavily on FMV titles to demonstrate their multimedia capabilities. These versions preserved the core mix of pre-rendered racetracks and live-action hosting, though technical compromises and differences in video quality were evident. While the ports never achieved the same cultural penetration as the bundled PC edition, they reflected the broader push of the era.

The Software Toolworks and Mindscape soon became part of the same family when, in 1994, The Software Toolworks was acquired for $462M by Mindscape’s parent company, UK media giant Pearson, effectively linking MegaRace’s European and North American distributors under one corporate roof. Their combined backing ensured the title reached both sides of the Atlantic with the marketing weight needed to stand out in a crowded and experimental multimedia landscape.

Reviews were mixed but intrigued. Computer Gaming World praised the graphics and presentation, nothing else looked quite like it, but criticized the repetitive gameplay and rigid controls. UK magazines like PC Format noted its originality, with Lance Boyle singled out as a highlight, though they too pointed out the shallow racing mechanics. By September 1995, MegaRace had sold 330,000 copies. Later marketing boasted of “1.5 million sold,” counting bundles and re-releases. For a mid-’90s multimedia title, it was a genuine success.

Cryo doubled down. MegaRace 2 arrived in 1996, once again starring Christian Erickson as Lance Boyle. This time, pre-rendered video tracks were overlaid with 3D polygon models for the cars, blending contemporary techniques.

MegaRace 2 kept the pre-rendered tracks that allowed for visual polish and intricate detail that few PCs could generate on the fly, while the new 3D polygonal vehicles made combat, collisions, and explosions more dynamic than before. It wasn’t a truly open track in the sense of a modern 3D racer, but it felt more interactive than the rigid rails of its predecessor. With multiple paths, shortcuts, and an expanded arsenal of weapons, the game offered players a greater sense of agency and variety.

By 2002, the third game, MegaRace 3, embraced fully real-time 3D graphics and added online multiplayer. But by then, the FMV craze was long over. Players had moved on to more dynamic 3D racers like Need for Speed and Wipeout.

FMV as a genre didn’t last. By the late ’90s, high production costs and limited interactivity had sealed its fate. Yet its influence endured, pushing developers to adopt new production pipelines and borrow techniques from the world of filmmaking. MegaRace was both a product and a parody of multimedia excess. Lance Boyle’s manic grin, Stéphane Picq’s pounding techno score, the neon blur of its surreal racetracks, a perfect time capsule of the FMV craze, a moment when games leaned hard into cinematic spectacle, chasing a future that never quite arrived.

In 2014, the Jordan Freeman Group and ZOOM announced plans for a modern revival, complete with updated versions of the original trilogy and a brand-new reimagining. Erickson returned to reprise his role as Lance Boyle, recording new footage more than two decades after his original performance. The project generated excitement among fans nostalgic for FMV’s campy glory, though the full reboot ultimately stalled and never materialized.

Sources: Wikipedia, Cryo Interactive retrospectives, MobyGames, GamePro Magazine, Substack…

One of the best racing games ever. I also loved the crude humor.

A fascinating game indeed, and a perfect showcase of the emerging technology. As a young aspiring 3D artist in the mid’90s I was blown away by the visuals…