Born in 1946, Jeffrey Stanton was a child of the post–World War II generation, growing up in an era when science and technology were shaping both industry and imagination. From an early age, he was drawn to how things worked, an interest that pointed him toward engineering. After graduating from James Madison High School in Brooklyn, he pursued higher education at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, where he earned a Bachelor of Mechanical Engineering in 1967 and a Master of Science in Mechanical Engineering in 1969. His career began in the aerospace industry, working at McDonnell Douglas and TRW Systems as a control systems and mechanical engineer. The work was precise, technical, and provided a solid professional track, but his interests soon began to drift.

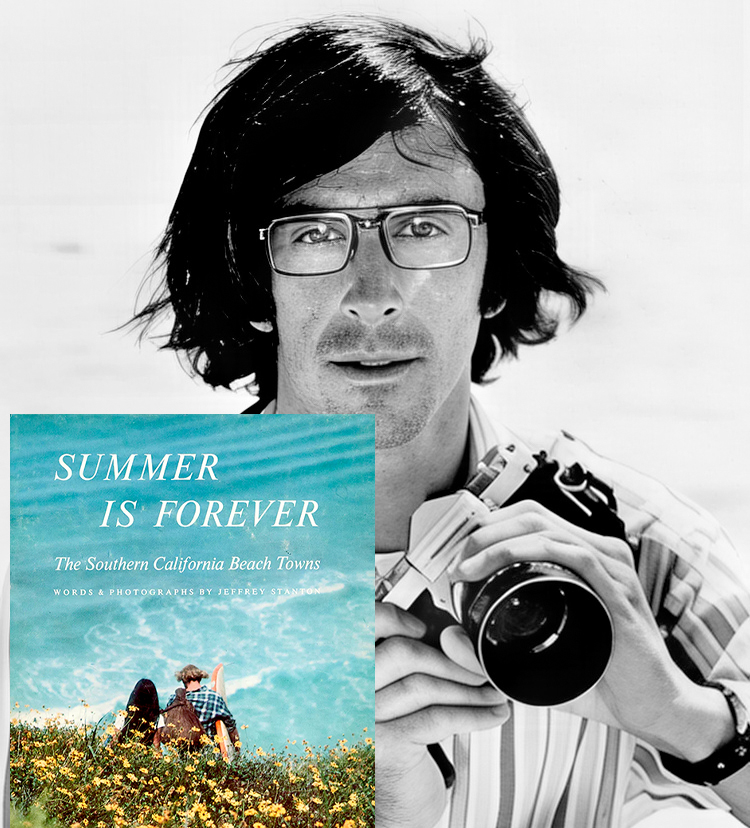

Stanton always balanced his technical training with creativity, and by the mid-1970s, he left engineering behind and started working as a freelance photographer and illustrator, publishing a photo-essay book in 1975 titled Summer is Forever, which captured the atmosphere of Southern California’s beach towns. He moved to Venice, a Los Angeles bohemian community that better suited his eclectic interests. From here, as one of the “original” still life photographers and Venice Boardwalk vendors, he ran a small postcard business, produced a cartoon-style tourist map, and immersed himself in the city’s history, culminating in a book chronicling Venice’s formative years between 1905 and 1930.

Jeffrey Stanton became a freelance photographer after he quit his engineering job in the mid-70s.

The photo of him was taken for his Summer is Forever book.

Image from westland.net

The turning point toward computing came in 1979 when Stanton purchased an Apple II computer. During the slower winter months of his postcard business, he began experimenting with programming, blending his analytical skills from engineering with his natural creativity. He explored the intricacies of 6502 assembly language and taught himself programming. He joined local computer clubs, swapped tips with other hobbyists, and invited neighborhood kids into his Venice studio to test his early contraptions. He even wrote reviews for hobbyist newsletters, placing himself at the center of the small but passionate Southern California computing scene.

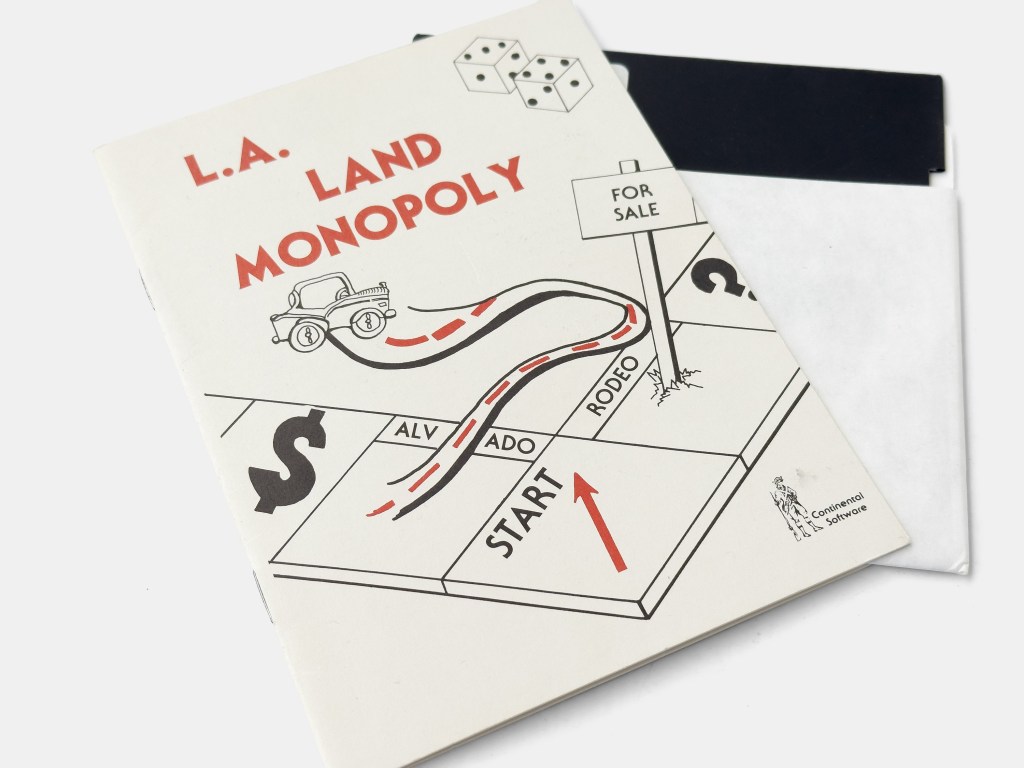

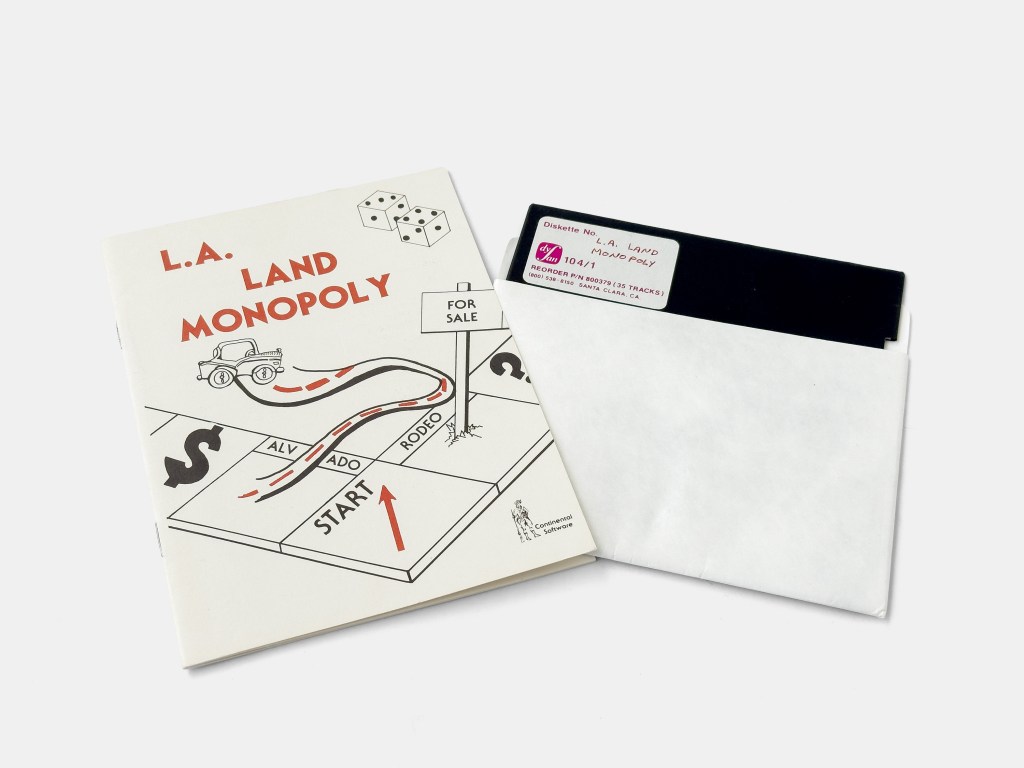

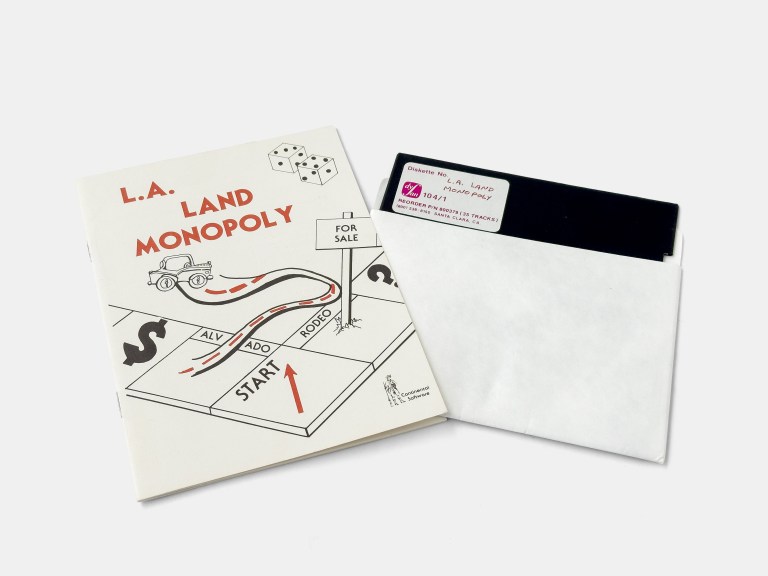

Stanton’s first commercial game was a reimagining of the classic board game Monopoly, given a distinctly Los Angeles flavor. Drawing on his familiarity with the city, he replaced the traditional property set with well-known local streets, transforming the familiar board into a tour of the City of Angels. Designed for two to six players, the game stayed faithful to Parker Brothers’ rules but streamlined play with computer-managed transactions, eliminating the bookkeeping that often slowed down tabletop games. Light animations and clear, functional graphics gave the game an inviting look, while the computer’s ability to handle property deeds, rent, and bank balances added a level of polish and efficiency uncommon in many early hobbyist titles.

L.A. Land Monopoly was picked up by Continental Software, a small Apple II label established by Los Angeles retailer and publisher James D. Sadlier. His ventures included The Book Company and the ComputerLand store of Lawndale, which provided both a ready distribution network and a base of local customers. Continental gave Stanton’s game a modest but real commercial platform, advertising it in Softalk magazine in September 1980 alongside titles like Hyperspace Wars and a handful of office utilities. For many Apple II owners in Southern California, it offered not only a digital take on a familiar favorite but one with a local identity.

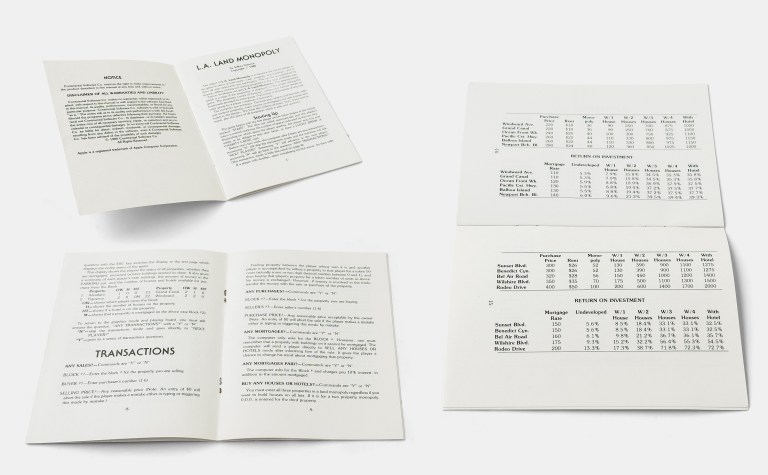

Jeffrey Stanton’s first commercial game, L.A. Land Monopoly, was published by Continental Software for the Apple II in the early Autumn of 1980.

It was marketed as a local-flavor twist on Parker Brothers’ classic, with Los Angeles streets replacing the traditional properties.

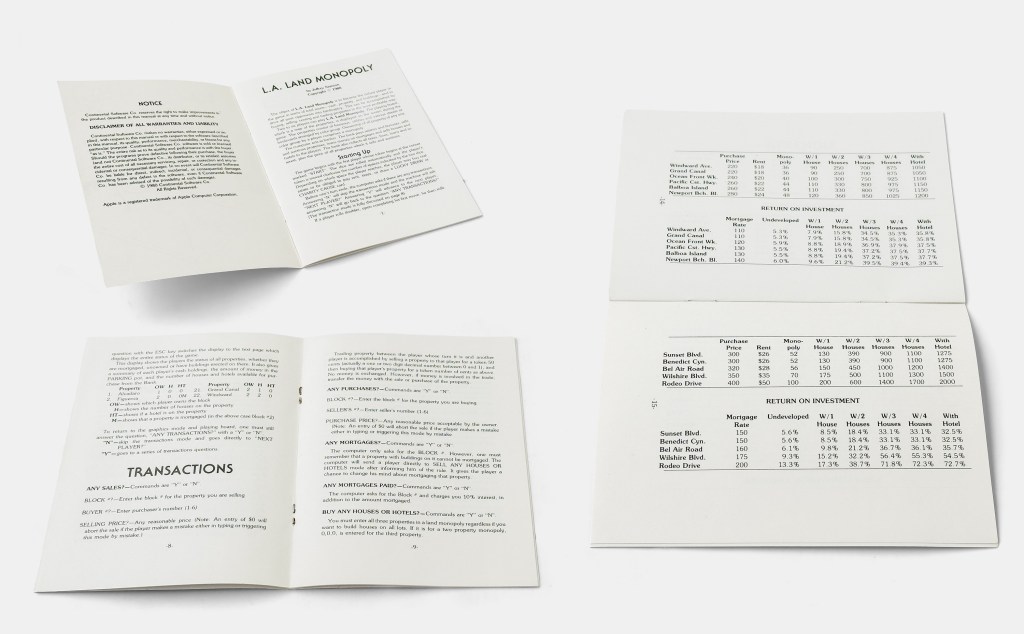

The game included a 16-page manual that detailed the rules, property values, and costs of houses and hotels, guiding players through Stanton’s Los Angeles-themed take on Monopoly.

Stanton’s digital reimagining of the classic board game allowed 2–6 players to buy and trade Los Angeles streets, with the computer handling money, property deeds, and transactions.

The game’s novelty lay in the blend of familiar gameplay and local flavor, making it a modest hit among Southern California Apple II users and a perfect reflection of Stanton’s mix of technical know-how and personal voice.

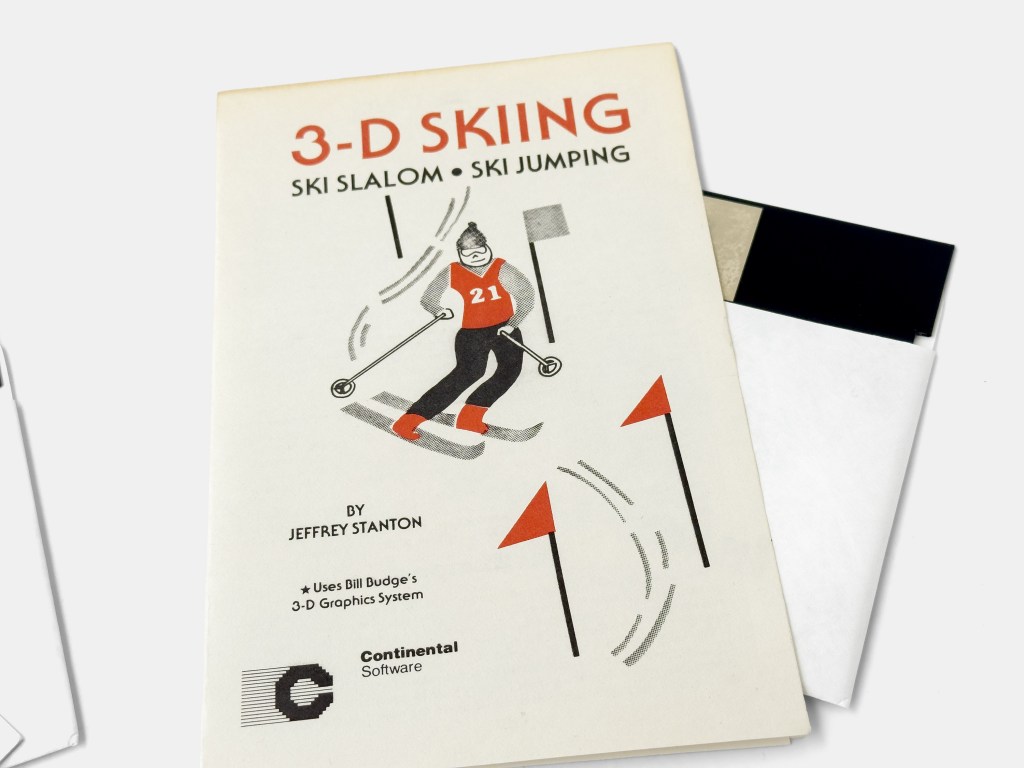

As an avid skier, spending considerable time skiing following his move west, and with fond memories of Vermont slopes from his college years, Stanton turned to the sport as the subject of his next project. Skiing gave him both a personal connection and a technical challenge on how to recreate the sensation of speed, depth, and movement on the Apple II’s limited hardware. It was the perfect testbed for his growing fascination with stretching the boundaries of computer graphics.

The fascination had begun with Bruce Artwick’s 1979 title, Flight Simulator, a program celebrated for its “real-time” wireframe 3D graphics. Having worked in aerospace, Stanton was intrigued by the idea that a home computer could calculate and render three-dimensional spaces and objects. He even modified the program’s database to replace its terrain with local landmarks, Marina del Rey harbor, and the Palos Verdes hills, places he knew and loved. Yet tinkering with someone else’s engine was not the same as building an original game from the ground up.

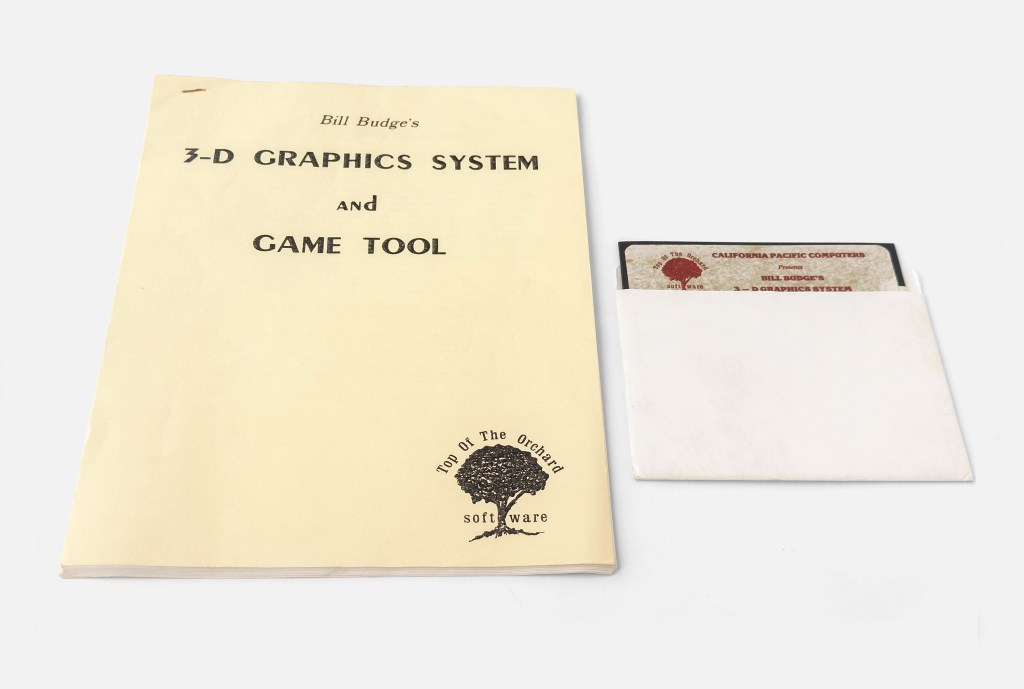

When programming prodigy Bill Budge introduced his 3-D Graphics System and Game Tool for the Apple II in 1980, he gave developers access to sophisticated routines, lowering the barrier to entry for those eager to experiment with early 3D. That winter, with his postcard and photography business in its seasonal lull, Stanton took full advantage of the opportunity. Budge’s tools allowed him to bypass some of the most difficult low-level coding challenges and instead focus on design and gameplay.

Programming prodigy Bill Budge, widely admired for his advanced graphics coding on the Apple II, released his 3-D Graphics System and Game Tool in 1980 through Al Remmer’s California Pacific Computer Company. The package gave hobbyists like Stanton access to powerful routines, enabling “3D” graphics and games.

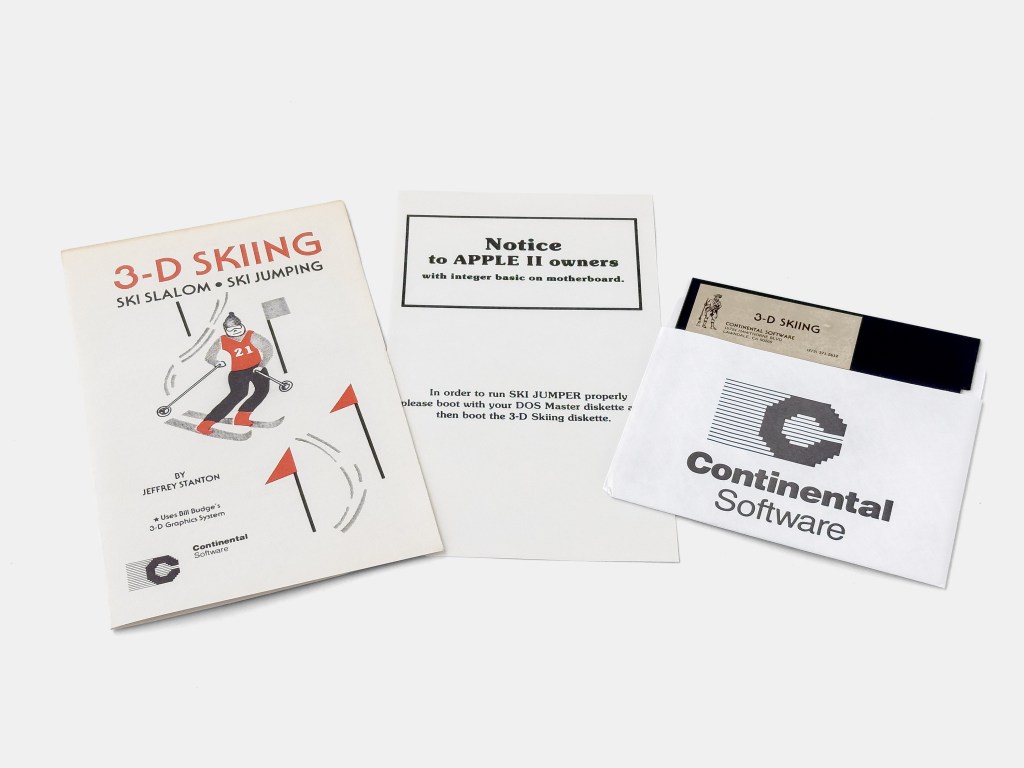

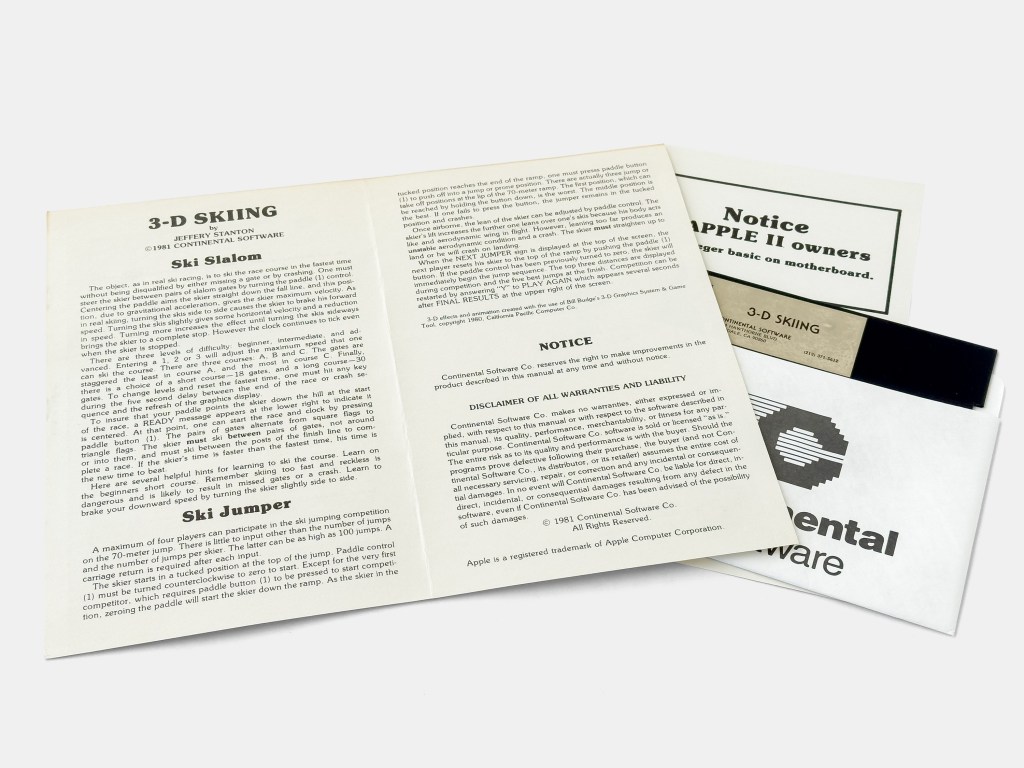

The result was 3-D Skiing, an ambitious attempt at forward-scrolling pseudo-3D. With the illusion of motion, created through scaled graphics and carefully timed assembly routines, players “hurtled” downhill against the clock, weaving through slalom gates. For Apple II owners, the effect was remarkable, dynamic, and fast-paced in a way few games of the era attempted. The package also included a second event, a more traditional 2D ski-jumping contest controlled with the Apple II’s paddles. Combined, the game stood out in hobbyist circles for its originality and technical daring, offering players a taste of perspective and speed at a time when most computer games were still locked into flat, static screens.

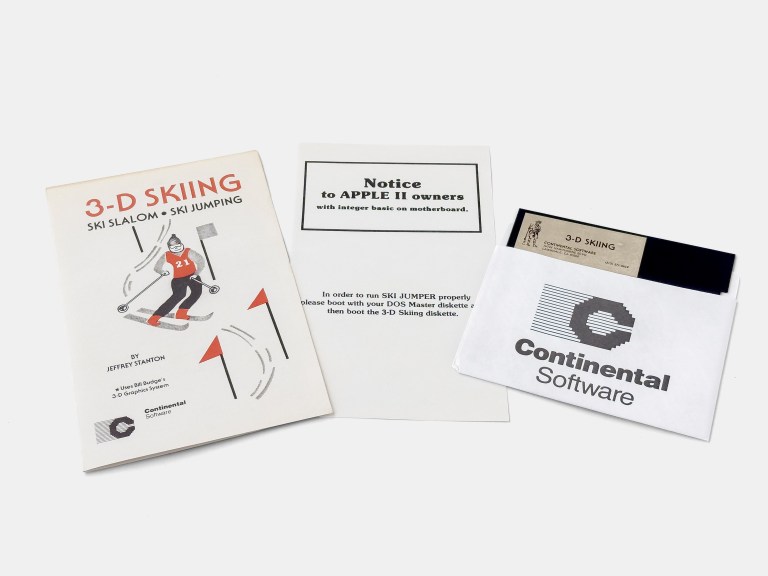

Jeffrey Stanton’s second and last game, 3-D Skiing, was, like his first, published by Continental Software for the Apple II in 1981.

3-D Skiing drops players onto the slopes for a fast, arcade-style run. The game combines slalom racing with a ski-jumping challenge, capturing the thrill of the sport in a way few computer titles managed in the early ’80s.

L.A. Land Monopoly and 3-D Skiing were sold by Sadlier’s local ComputerLand store and distributed through mail order and user group newsletters. While Reviews were limited, they were generally positive, with enthusiasts appreciating the local references in Monopoly and being impressed by the pseudo-3D effect of 3-D Skiing.

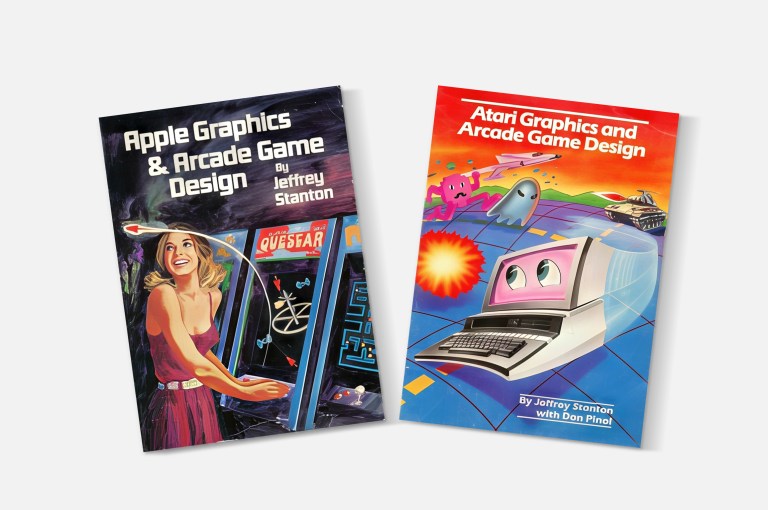

By 1982, Stanton had begun sharing his knowledge more broadly. That year, Sadlier’s The Book Company published Stanton’s Apple Graphics & Arcade Game Design, a how-to book that guided hobbyists through the creation of their own arcade-style graphics and games. Around the same time, Stanton purchased an Atari 800 home computer, which he admired for its advanced capabilities, multiple graphics modes, hardware sprites with collision detection, and a dedicated sound chip. Together with Dan Pinal, he co-authored Atari Graphics & Arcade Game Design, released in 1984. These books became essential reading for aspiring programmers, helping bridge the gap between hobbyist curiosity and professional technique.

Apple Graphics & Arcade Game Design and Atari Graphics & Arcade Game Design, Jeffrey Stanton’s two influential programming guides from 1982 and 1984, respectively.

Both taught hobbyists how to create arcade-style games, bridging the gap between curiosity and technical mastery on home computers.

Stanton’s reputation brought him to the attention of the industry. In April 1983, he was offered a part-time consulting position with Atari’s 5200 division, a $25,000-per-year role that would have had him flying from Los Angeles to Silicon Valley each week. But just as the opportunity arose, Atari suffered a $300 million quarterly loss, and all consultant contracts were canceled, a stark reminder of how volatile the early video game industry had become. By the end of the year, the North American video game crash was in full effect.

By the mid-1980s, Stanton had largely stepped back from computing. The industry was shifting toward bigger publishers and more commercial projects, leaving less space for independent experimenters. He returned to photography, writing, and his ongoing historical research on Venice. Yet his time in games left a small but distinctive mark. L.A. Land Monopoly and 3-D Skiing captured both his sense of place and his technical imagination, while his programming books gave thousands of readers the wisdom and tools to begin creating games of their own.

sources: Internet Archive, MobyGames, Creative Computing, Jeffrey Stanton – Biography at westland.net, Wikipedia, Softalk…