In the spring of 1980, Ken and Roberta Williams were unknowingly about to change gaming. Working out of their small home in Simi Valley, California, their first game, Mystery House, had just been completed. A collaborative effort and bold experiment in combining text and crude vector graphics on the Apple II. To promote it, Roberta placed a full-page advertisement in Micro 6502 magazine. One game alone wouldn’t make a catalog, so two additional titles, Skeet Shoot and Trap Shoot, both developed by an outside programmer, were also featured, bearing Ken’s company’s On-Line Systems name. While the two additional titles soon faded into obscurity, Mystery House, the first adventure game to feature graphics, became a breakthrough hit, and the Williamses quickly began expanding their catalogue, bringing in a mix of original creations and third-party contributions. Among the early contributors was a young programmer named Mark Allen.

Allen’s interest in computers began during his college years at the University of California, San Diego. Here, he met Richard Gleaves, and together they developed a 6502-based interpreter for the Pascal programming language, an effort that would later form the foundation of Apple Pascal. Their work caught the attention of Apple Computer, including the late Bill Atkinson, who offered both jobs at the Apple headquarters in Cupertino. A golden opportunity, but Allen and Gleaves turned it down, preferring to stay in Southern California where they could continue independent projects on their own terms.

Despite turning down the offer, Allen’s first published game, Stellar Invaders, was picked up by Apple and published in 1980 in the Apple Entertainment Series. It was a nimble and technically impressive Space Invaders clone and showcased smooth animation and sound effects that squeezed surprising performance from the Apple II’s modest 1 MHz processor.

The following year, Allen put his own spin on the fixed shooter formula with Sabotage, an influential title that was picked up by Ken and Roberta’s company and released for the Apple II in the summer of 1981. The game became a hit, earning praise for its originality and addictive gameplay. It ended up at 16th place on Softtalk’s Reader’s Poll Top-Thirty chart of 1981. Like most early titles, it was vastly pirated and became one of the most-played games on the Apple II that year.

Sabotage went on to become a classic with its original fast-paced gameplay, animations, and sounds, spawning numerous clones in the years to come. Including one of the most important early x86 titles, Paratrooper, created by Greg Kuperberg and published by Orion Software in 1982.

Mark Allen’s second game, Sabotage, was published for the Apple II in the summer of 1981 by Ken and Roberta Williams’ On-Line Systems. The game quickly became one of the standout hits of the year, celebrated for its clever twist on the fixed-shooter genre. Its innovative gameplay inspired numerous clones in the years that followed.

1982 marked a new direction for On-Line Systems. With investment from venture capitalist Jacqueline C. Morby of prestigious TA Associates and the company’s recent move to the foothills of the Sierra Nevada Mountains in central California, the company was rebranded to Sierra On-Line. The rebrand was more than cosmetic. Sierra, no longer just a handful of programmers, was positioning itself as a full-spectrum developer and publisher.

In an attempt to organize its growing portfolio, dedicated sub-brands were created with SierraVenture housing graphic adventures and fantasy games, and SierraVision, dedicated to the company’s arcade-style and cartridge-based games for systems like the Apple II, VIC-20, and the Atari 8-bit line of home computers.

The move reflected a broader trend set by industry leaders, Atari, Activision, and Parker Brothers, who cultivated strong brand identities through a steady stream of both arcade-inspired hits and original creations across multiple platforms. Williams saw SierraVision as a way to place the company in direct competition with the giants, and crucially, to secure shelf space in mainstream retail outlets that catered more to cartridge games than to floppy-disk software.

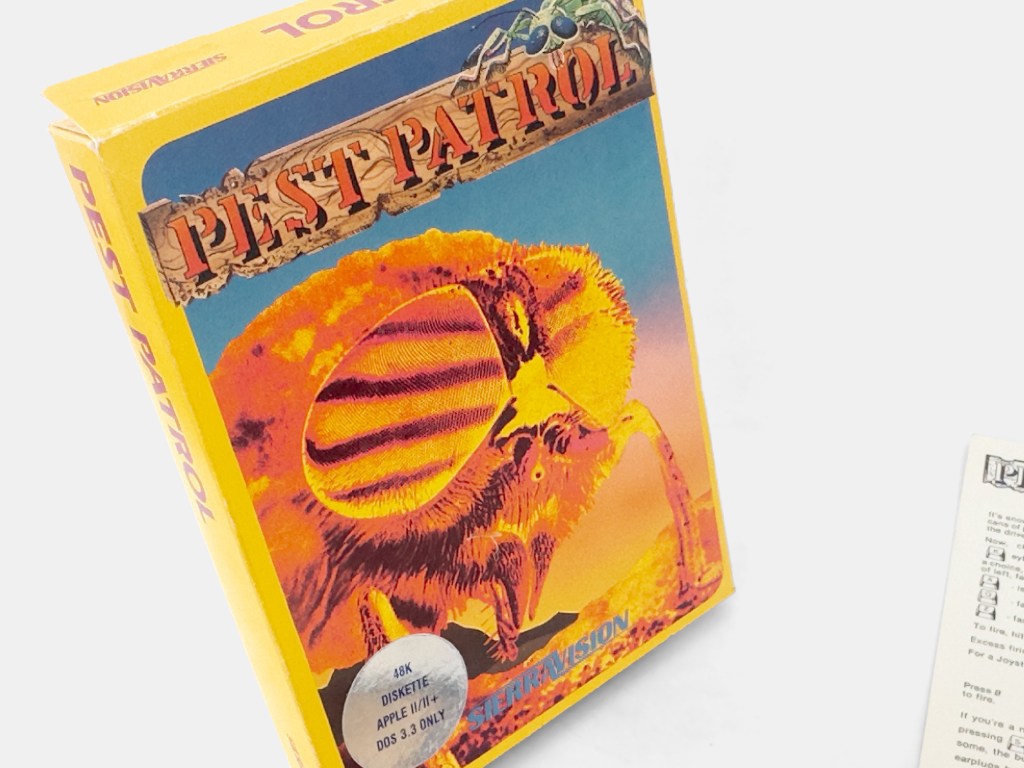

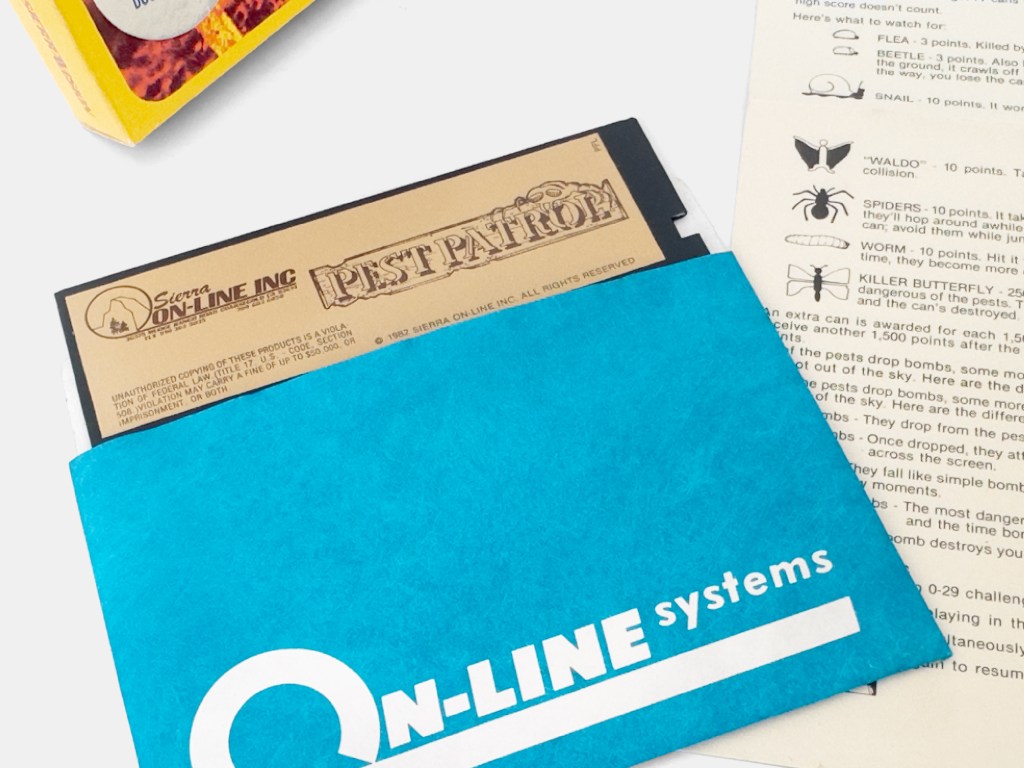

To promote the launch of SierraVision, Sierra abandoned its familiar Zip-lock bag packaging in favor of sturdier, full-color boxes designed to stand out on store shelves. It was a costlier approach, but one that signaled a more ambitious, polished, and cohesive product line. The label launched with a mix of both third-party and internally developed titles, including Frogger, Crossfire, Cannonball Blitz, Jawbreaker, and Threshold. The goal was to establish SierraVision as a recognizable brand that consumers could trust for quality action games, much like Activision’s name carried cachet with Atari owners.

But there were challenges. Sierra’s strength lay in computer-based software, and the console market was a different beast altogether. The market was intensely competitive, arcade conversions and clones flooded store shelves, and smaller publishers found it hard to differentiate their products. Still, in late 1982, optimism ran high. SierraVision had its lineup, its branding, and its place in the holiday season rush. Among the releases was Pest Patrol, Allen’s newest game.

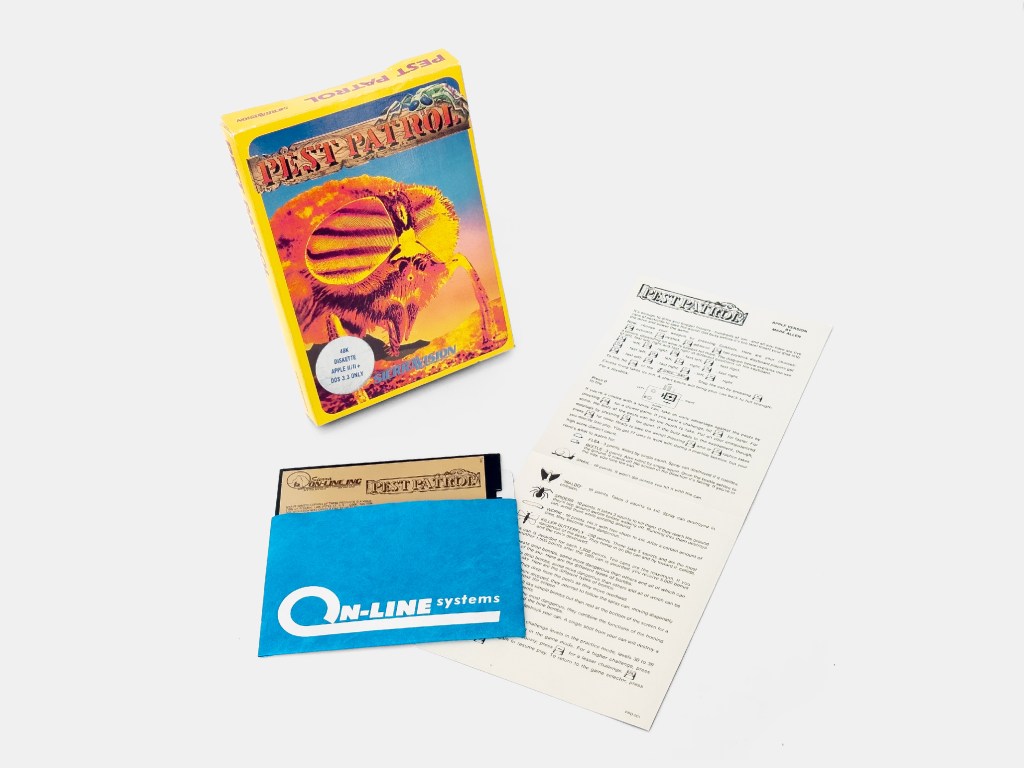

Released for the Apple II in the autumn of 1982, Pest Patrol was among the first titles to carry the newly minted SierraVision label. For Allen, it marked the third and final entry in his short but distinctive career as a game designer. Like his earlier works, the concept drew inspiration from Space Invaders, yet once again, he reimagined the formula with his own inventive twist.

Mark Allen’s third and final game, Pest Patrol, was released for the Apple II in the autumn of 1982 under Sierra On-Line’s newly launched SierraVision label.

As one of the first titles in the label’s short-lived lineup, it reflected Sierra’s early ambitions to expand into arcade-style action games, bringing fast-paced, home-computer-friendly gameplay to a growing audience.

The box and vibrant cover art were part of Sierra’s strategy to appeal to a broader audience and establish the SierraVision label as a recognizable brand in the action game market.

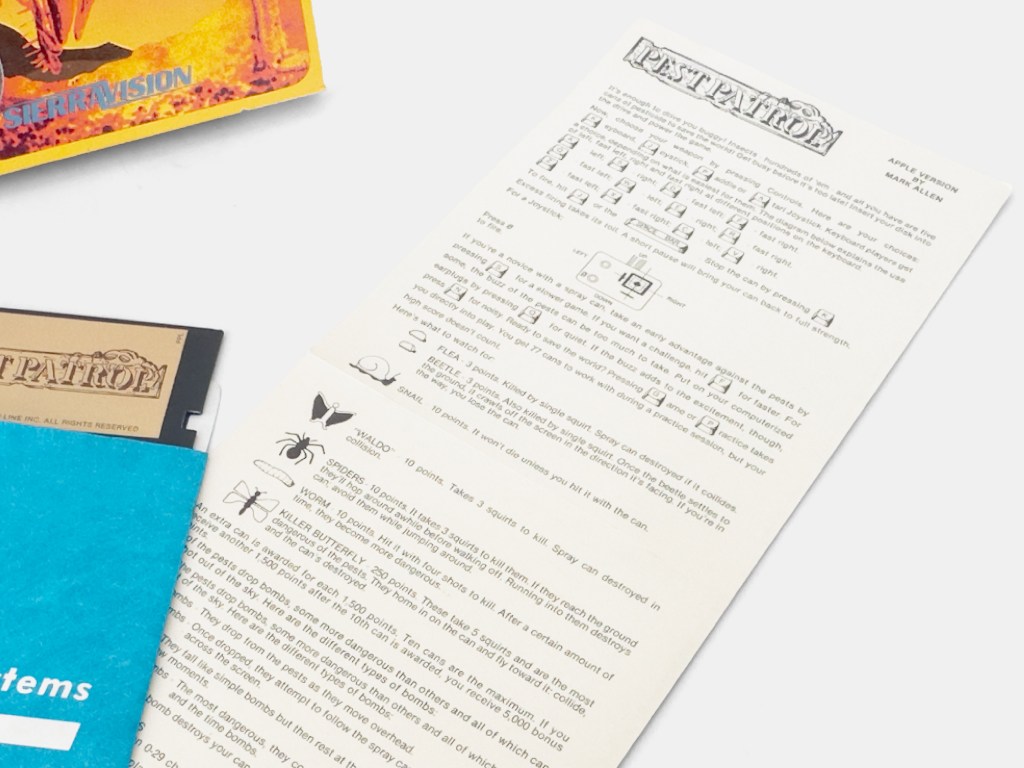

The battlefield is your backyard, and your only weapon against enemies is a can of pesticide, spraying at incoming waves of insects and critters of all sorts, in classic Space Invaders fashion.

The game featured forty levels, each with its own unique attack pattern. The first twenty-nine could be selected via the plus key in practice mode; the remaining ten were accessible only by playing through the game normally.

Like his earlier work, Allen combined crisp control with interesting enemy design and tight animation. The game felt fast and reactive on the now five-year-old Apple II, a notable feat given the machine’s modest hardware.

The optimism of late 1982 wouldn’t last. The industry-wide collapse of 1983–84 devastated the industry. Console and many cartridge-based systems saw collapsing sales. Unsold inventory piled up in warehouses, with some games, famously, ending up in landfills. Cartridge production was costly and slow, and when sales dried up, companies like Sierra found themselves holding expensive, unsellable stock.

Ken Williams, looking at the financial damage, reportedly vowed never to make another console game. SierraVision, once positioned as the company’s action-gaming brand, quietly disappeared.

While Pest Patrol delivered fast-paced action and tight, responsive controls, it remained a fundamentally simple arcade-style game. The Space Invader concept had largely exhausted itself, and despite its charm, the game struggled to stand out, selling only in very limited numbers. By late 1982, the home computer market was beginning to demand more complex experiences, with deeper gameplay, varied objectives, and longer-lasting challenges. In that context, Allen’s straightforward swatting of pests, though enjoyable, paled next to the richer, more ambitious titles emerging from both Sierra and its competitors. Its simplicity, while part of its appeal, also highlighted the changing expectations of players and the inherent limits of the SierraVision experiment in an industry that was evolving rapidly.

Following Pest Patrol, Mark Allen stepped away from game development. His name faded from the industry as Sierra doubled down on adventure games, eventually building empires from titles like King’s Quest, Space Quest, and Leisure Suit Larry. While Sabotage retained a measure of fame thanks to its widespread cloning, Pest Patrol became one of Sierra’s more obscure releases, a clever, well-made game that never had a chance to find its place in the market.