By 1982, the home computer software market was evolving fast. What had begun just a few years earlier as a freewheeling space dominated by garage developers and bedroom coders was now becoming an industry. While most games were still written by individuals, the rules were changing. Marketing, packaging, and distribution were becoming just as important as the software itself. Companies like Brøderbund, Activision, and On-Line Systems, soon to become Sierra On-Line, had grown from scrappy startups into the industry’s most influential players.

These firms not only developed best-selling games in-house but increasingly acted as publishing powerhouses for third-party titles. They understood the value of visibility, shelf space, and speed. Success meant not just writing a good game, it meant getting it seen, shipped, and sold in volume. It was the beginning of the end for the sole developer-publisher.

Matthew Jew was part of a generation of developers who came up just before the industry professionalized. Based in San Francisco, Jew had, along with Erik Kilk, created Battleship Commander back in 1980. A digital text-only version of the board game Battleship, made for the Apple II. The game was picked up by Bob Christiansen‘s Quality Software, one of the early and well-respected publishers in the industry. Though the game wasn’t a hit, it was included in the company’s marketing push, appearing, alongside other Quality Software titles, in a full-page ad in Softalk magazine. For Jew, it was a modest but professional debut, and his first glimpse at what it meant to have a publisher behind you.

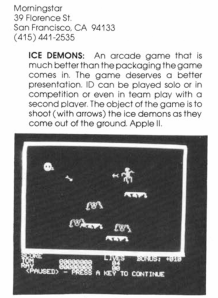

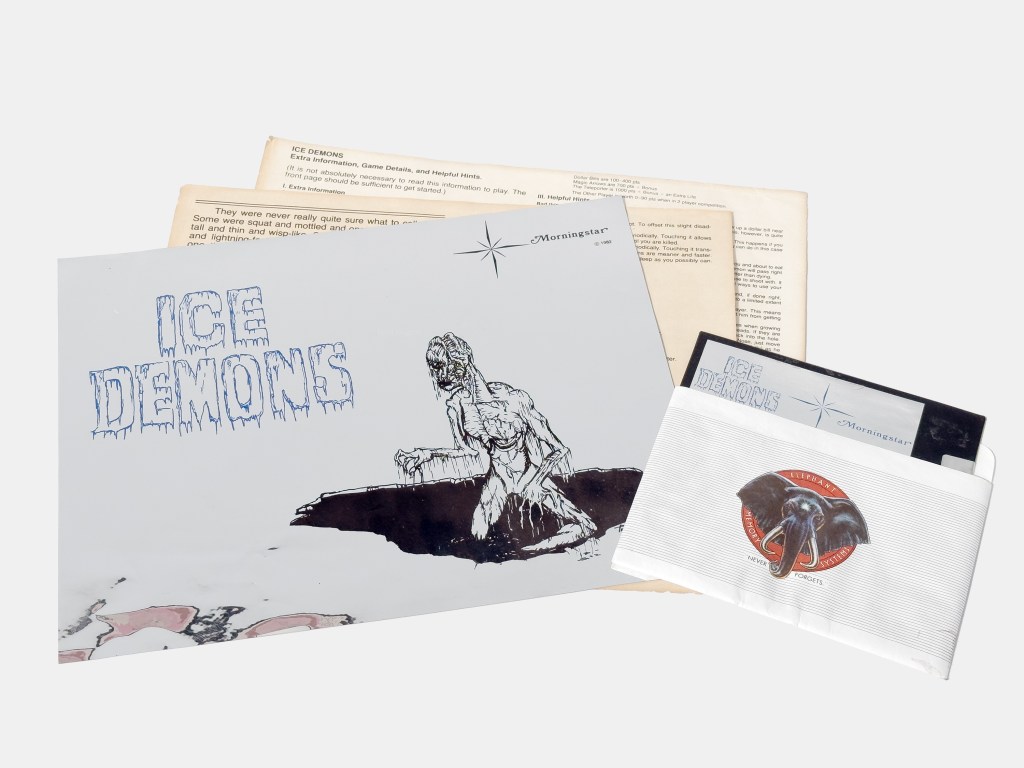

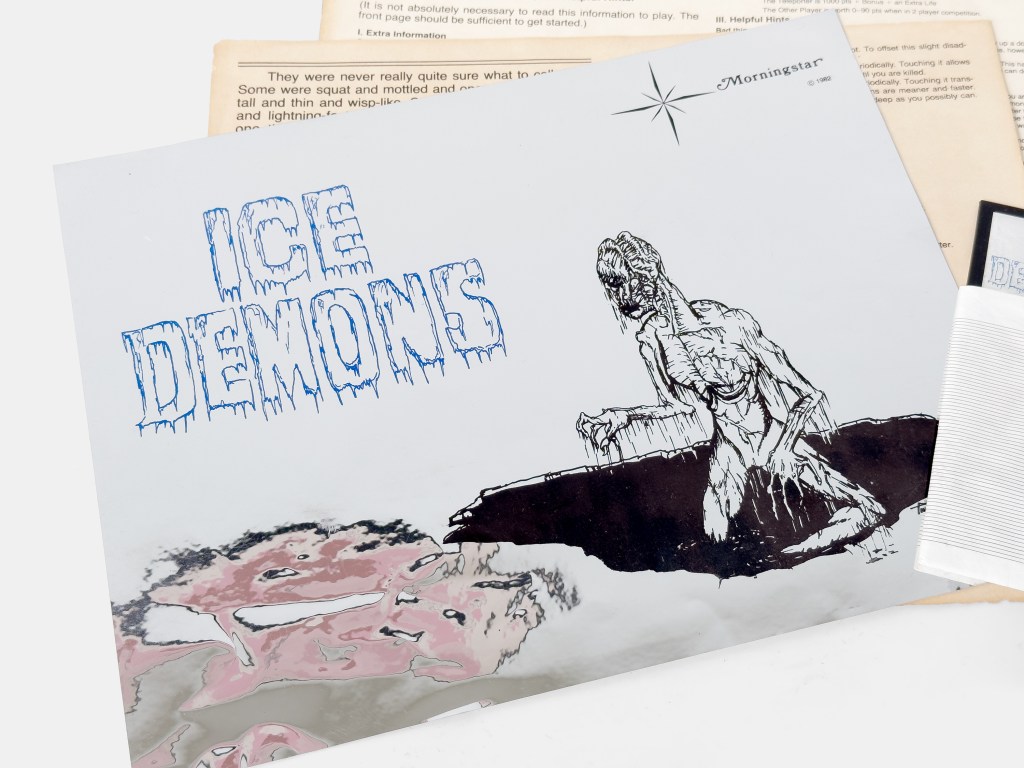

While doing commercial work as a freelancer, in 1982, Jew found time to fulfill a new game idea. This time, he decided, as pioneers before him, to publish and market the game himself. Jew knew the Apple II and its intricate hardware well, and with high ambitions, he went to work on Ice Demons, a fast-paced, paddle-controlled shooter for the Apple II, simple in concept but impressively executed. Jew crafted the game’s graphics using the VersaWriter, a digitizer board that allowed developers and artists to trace hand-drawn illustrations into Apple II Hi-Res graphics format. Ken Williams of On-Line Systems had used the same system two years earlier to create Mystery House, the first graphical adventure.

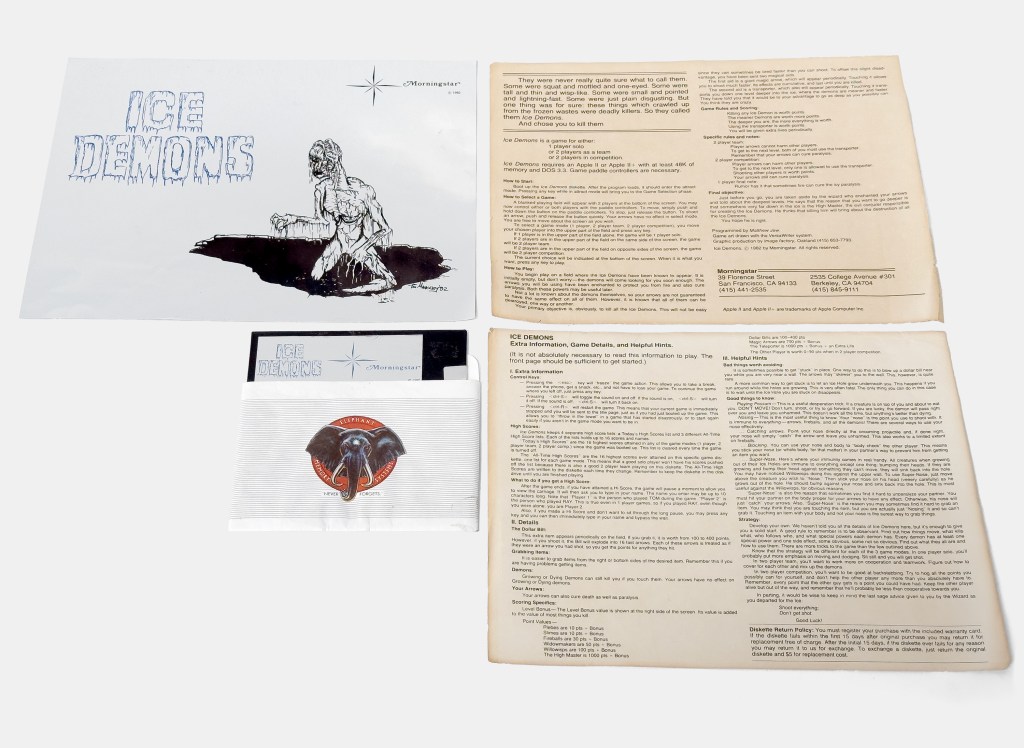

Jew took it upon himself to market and publish the game. He enlisted Image Factory, a small Oakland-based studio, to handle the game’s physical aspects. Unlike the plain sleeves and photocopied labels that adorned most small-scale releases, Ice Demons shipped with a dazzling mirror-like cover evoking the sharp, icy shards from which the demons in the game emerged. The artwork was screen-printed directly onto the reflective surface, resulting in a product that felt extremely premium. For publishing, he created the Morningstar label.

The original signed cover artwork and mirror-like appearance spoke volumes about Jew’s ambitions. This wasn’t a quick release or a throwaway game. Everything about Ice Demons was carefully considered, from gameplay to packaging, a self-contained, well-crafted effort.

Ice Demons, Matthew Jew’s second game, was published for the Apple II in 1982 under his Morningstar label.

Its striking cover—metallic, mirror-like card stock with screen-printed artwork- was anything but ordinary.

The mirror-like finish shimmered like shards of ice.

Ice Demons waste no time on story, besides a brief introduction in the manual, but opens with an ambitious touch – an impressive title screen accompanied by Bach’s Toccata and Fugue in D Minor.

Players control smiley-face characters, rotating left or right to aim arrows at “ice demons” erupting from holes in the platforms.

The game is controlled using Apple II paddles, a somewhat unusual design decision, even by 1982 standards.

The controls aren’t forgiving, and scoring takes practice.

Jew submitted Ice Demons to Softalk magazine, hoping for that all-important review that could help an independent title break through the noise. It arrived in the February 1983 issue. The verdict was mixed but respectful: “Although marred by poor animation, rather boring sound effects, and occasional image flicker, the inventive quality of the concept plus its totally unique modes of play make Ice Demons a significant game and Morningstar a company to watch.”

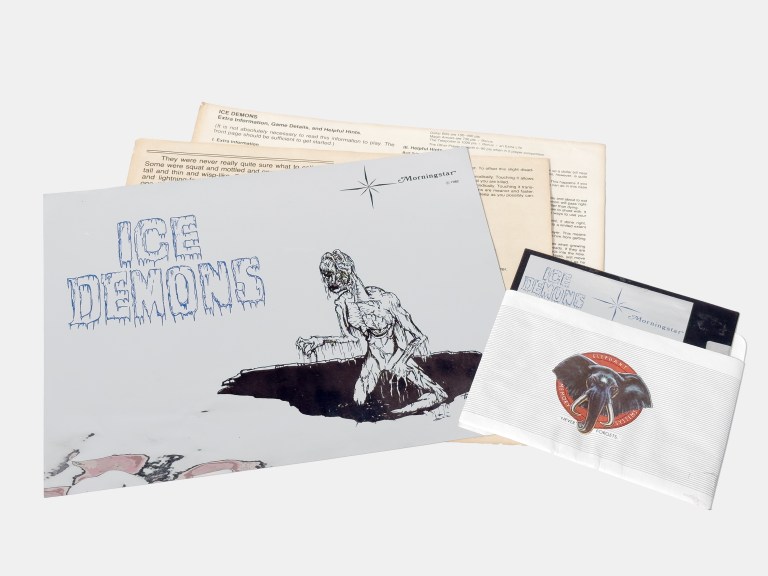

That same month, Ice Demons earned a brief mention in Computer Gaming World’s “Taking a Peek” section, where it was summarized in a few lines, between dozens of new releases jostling for attention in the rapidly expanding marketplace.

Ice Demons was briefly mentioned in Computer Gaming World Issue 8, January/February 1983. The writer expressed admiration for the game itself, but, somewhat oddly, seemed underwhelmed by its packaging, overlooking what was arguably its most distinctive and striking feature.

In 1983, Softline magazine listed Ice Demons in its high-score table, alongside major hits of the era. Steve Williams of Washington submitted a 1-player score of 48,990, while he and friend Dan Knight posted a 2-player record of 612,290. The exposure wasn’t much, but it was enough to confirm that someone, somewhere, had played the game. Beyond that, there was silence.

Like many solo developers of the early ’80s, Jew wore many hats: programmer, producer, publisher, and marketer. The ambition was undeniable, but the market was changing rapidly. Ice Demons was released into an increasingly crowded space where visibility was everything. Without a distributor or marketing campaign, only a limited number of copies were ever sold. Like many independently released titles of the era, it quietly and quickly faded into obscurity.

Following Ice Demons, Jew remained active in software, but his name never again appeared on a commercial game. Morningstar released no further titles. That one shimmering cover was both its debut and its finale. It captured something essential about its time: the possibility for a single developer to do everything, design, code, and publish. But it also stood as quiet proof that those days were numbered. By the mid-1980s, the industry had shifted. Shelf space was limited, distribution channels were locked, and publishers now demanded exclusive rights, rapid production, and market-ready polish. The idea of mailing out a game with a home address on the label was becoming quaint, if not entirely obsolete.

Decades later, the door reopened. With digital distribution, new tools, and global platforms, independent developers could once again create and release games on their own terms. The same dream, reimagined. Today, with the right idea and execution, a solo creator can reach an audience on a scale that even Jew, back in 1982, could hardly have imagined.

Jew moved between freelance and commercial software work. Between 1981 and 1986, he authored several programs, including a high-performance sorting library and low-level tools for devices and drivers. After that, his name faded from the public-facing tech world. His LinkedIn profile reflects a continued career in consulting, spanning operating systems, telephony, and insurance systems, but no further games.

Sources: Micro 6502 Journal, February 1983, LinkedIn, Softline Issue 3.1, Computer Gaming World Jan/Feb 1983, Softalk Feb 1983…

-There’s very little information available on Matthew Jew and Ice Demons. The Morningstar name had no prior software history and would release no other titles. The manual listed two contact addresses: one at 2535 College Avenue in Berkeley and another at 39 Florence Street in San Francisco. The latter was Matthew Jew’s residence at the time. Evident that Morningstar was a publishing label created by Jew himself to release Ice Demons independently.