By the early 1990s, Lethal Weapon, the mismatched buddy-cop franchise starring Mel Gibson and Danny Glover, had evolved into one of Hollywood’s biggest action franchises. Across three blockbuster movies released between 1987 and 1992, Reckless Martin Riggs and cautious Roger Murtaugh became household names, embodying the volatile mix of chaos and control that defined late-’80s and early-’90s action cinema.

When Lethal Weapon 3 hit theaters in May 1992, Ocean Software was already positioned to strike. The Manchester-based publisher had built a reputation, and much of its business model, on the swift acquisition and monetization of movie licenses. From RoboCop to Batman, The Untouchables to The Addams Family, Ocean had become synonymous with movie tie-ins in Europe. Their approach was quite pragmatic – secure the rights to a hot property, develop a game quickly and affordably, and ride the marketing wave before the buzz wore off. Results varied wildly, but the formula worked often enough to keep Ocean at the forefront of the European games industry for over a decade.

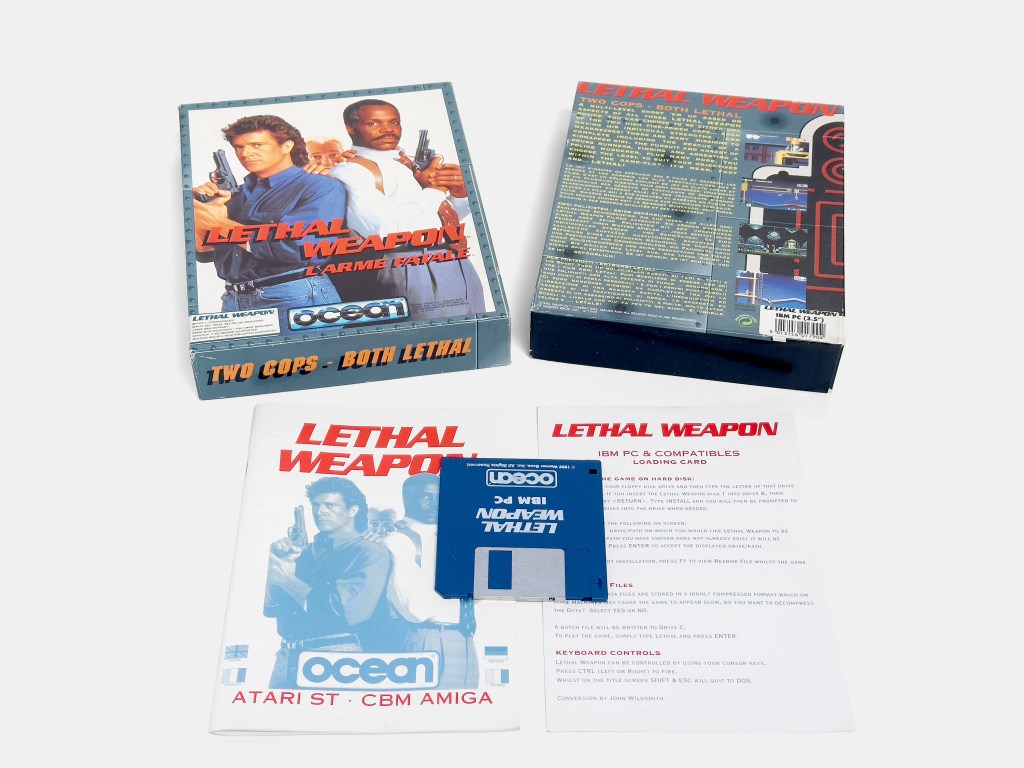

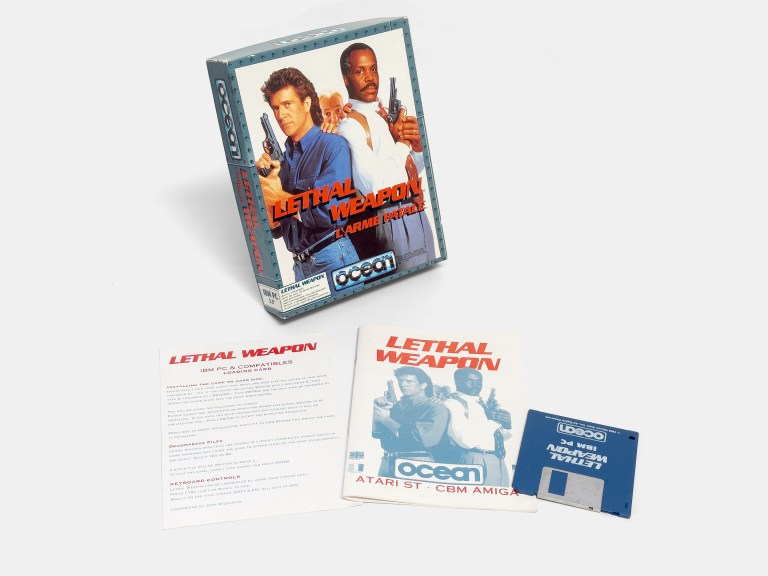

Development was handled in-house in Manchester with the Commodore Amiga being the flagship version, versions for the IBM PC and Atari ST were developed concurrently and shared the same core gameplay and design philosophy. Rather than attempt a faithful retelling of any single Lethal Weapon movie, the developers chose to draw loosely from all three existing entries, crafting a standalone story that functioned more like a highlight reel of generic urban crime-fighting. The decision wasn’t unusual. Ocean often prioritized gameplay tropes over narrative fidelity, especially when working under tight deadlines tied to a movie’s theatrical release. With Lethal Weapon 3 already in cinemas, the clock was ticking. The game engine was repurposed from earlier Ocean platformers, with the developers refining sprite handling and scrolling while reusing much of the underlying codebase.

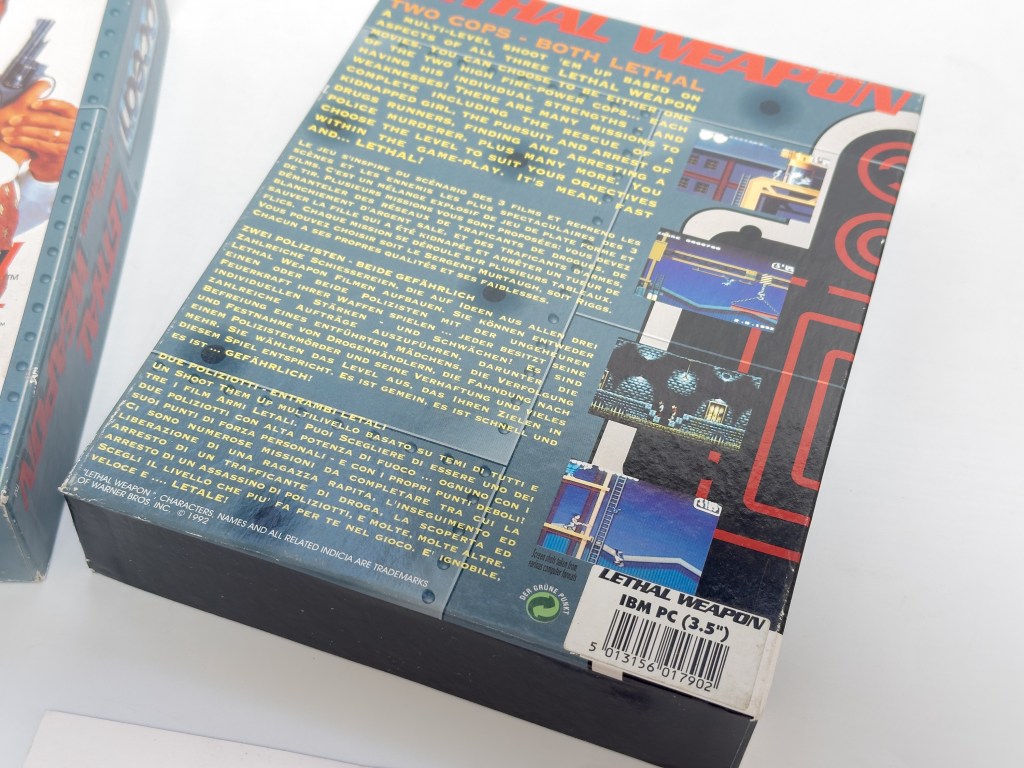

The overall structure was simple, four primary missions, each set in a different Los Angeles crime zone, culminating in a fifth and final mission unlocked only after completing the others. Gameplay combined side-scrolling platforming with light puzzle elements. Combat leaned into shoot-’em-up conventions, while platforming demanded pinpoint precision. Health pickups were rare, difficulty spikes were frequent, and the absence of narrative or cutscenes made the experience feel more like a generic action title than a cinematic adaptation.

The soundtrack, composed by Dean Evans with help from Barry Leitch, stalwarts of Ocean’s in-house audio team, matched the game’s tempo with synth-heavy tension. While their work bore no resemblance to Michael Kamen’s jazzy orchestral scores from the films, it offered energy and atmosphere. Sound effects were sparse due to storage constraints.

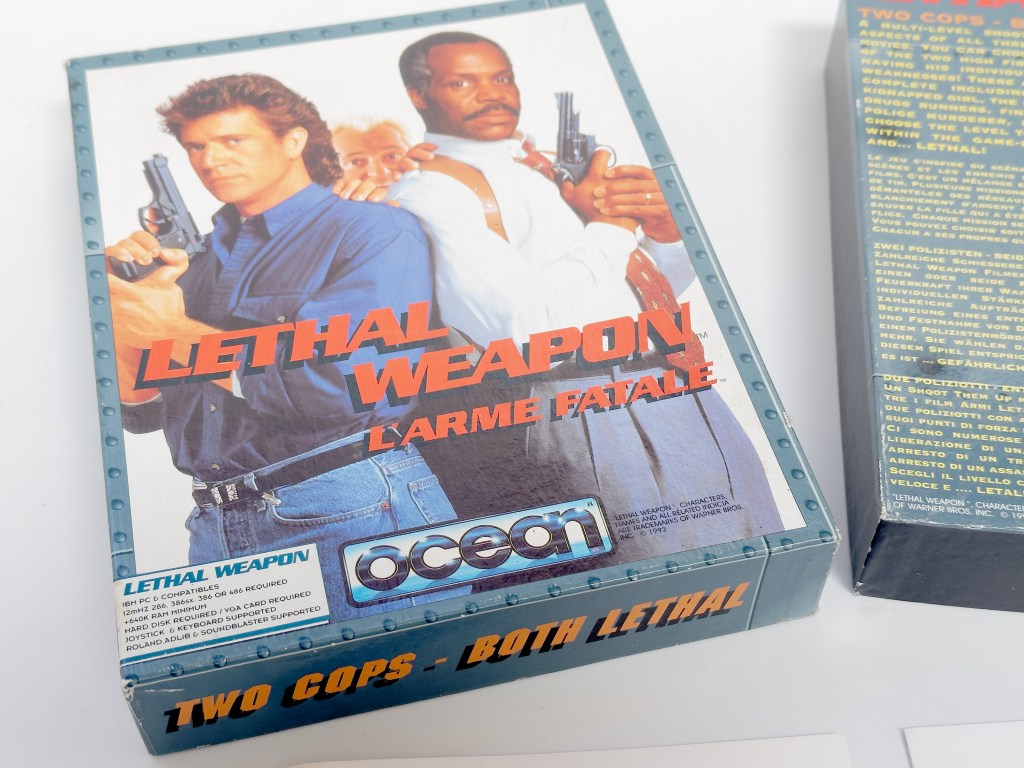

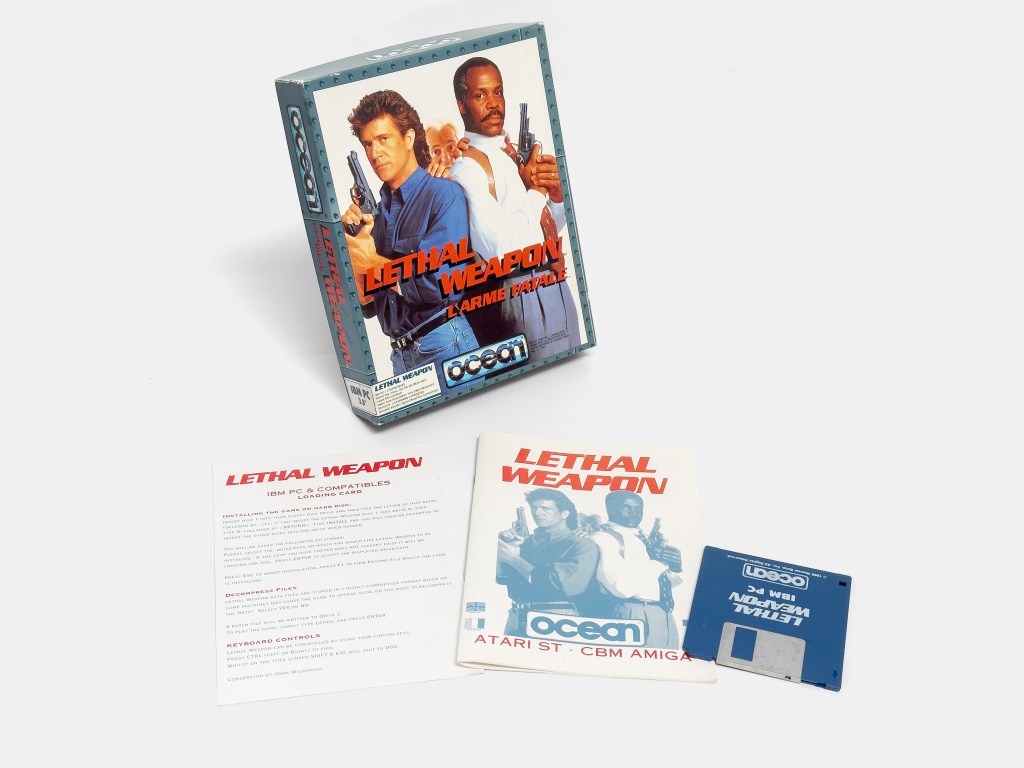

Lethal Weapon was developed and published by British powerhouse Ocean Software for the IBM PC, Commodore Amiga, and Atari ST in late 1992.

The IBM PC version suffered from choppier scrolling and color limitations unless run on a high-end VGA machine. It also had slightly altered sound effects due to varying hardware support.

The game’s production cycle was tightly bound to Lethal Weapon 3’s theatrical release. Development reportedly wrapped in under six months, a timeline that left little room for innovation. Mechanics were recycled, level design was functional but at times uninspired, and it sure looked like the game existed primarily to capitalize on a moment.

The Commodore Amiga release, bright, bold, and unmistakably early-’90s, is the definitive version, featuring vibrant backgrounds, smooth scrolling, fluid character animation, and a great synth soundtrack.

Gameplay consists of side-scrolling action with precision platforming, shooting, and boss fights across a crime-ridden Los Angeles.

Though players can choose to play as either Riggs or Murtaugh, the characters were functionally identical apart from their sprites. There are no unique abilities, dialogue differences, or gameplay changes, as otherwise stated on the back of the box, one of several points of criticism in contemporary reviews. The end-level bosses in the game were original creations by the developers and not characters from the films. The design leaned into comic book exaggeration rather than the grounded (if explosive) tone of the Lethal Weapon movies.

Critical reception was lukewarm. Reviewers praised the visual presentation, particularly on the Amiga, but criticized the shallow gameplay, uneven difficulty, and repetitive structure. Amiga Format described it as “a competent shooter that lacks any real connection to the films,” while CU Amiga found it “technically solid, but ultimately uninspired.”

For players expecting cinematic storytelling, memorable characters, or explosive set-pieces, Lethal Weapon delivered none of it. It was an action-platformer with a license slapped on, a game that could have been reskinned with almost any IP.

Despite its flaws, Lethal Weapon sold reasonably well, especially in Europe. The recognizable branding and well-timed release helped drive sales, even if player engagement waned quickly. By the mid-1990s, players and critics began demanding more from licensed titles, more story, polish, and a stronger justification for the game’s existence.

Lethal Weapon was one of the last Ocean tie-ins to succeed on branding alone. The company’s reliance on movie licenses, once its defining strength, became a liability as development budgets grew and player expectations rose. By the end of the decade, Ocean, once a pillar of British game publishing, had been absorbed by French publisher Infogrames, bringing a storied chapter in European gaming to a close.

In 1993, Lethal Weapon arrived on the Nintendo Entertainment System. Developed separately by Eurocom and published by Ocean, the version featured different level designs, music, and gameplay mechanics. Though it shared the name and premise, it was essentially an entirely different game.

Lethal Weapon was a product of tight deadlines, marketing-driven design, and a time when brand power could momentarily outweigh gameplay substance. It was a game made to capitalize on the moment, and like so many movie tie-ins of its time, it faded with it.

Sources: Wikipedia, Mobygames, Amiga Format, CU Amiga, Ocean: The History by Chris Wilkins…