The 1980s marked a golden age for post-apocalyptic storytelling, fueled by Cold War anxieties and a fascination with dystopian survival. Movies like Mad Max 2: The Road Warrior and Escape from New York, both from 1981, depicted bleak, lawless futures where survival hinged on resourcefulness, cunning, and sheer brutality. The dystopian themes spread throughout popular culture, influencing everything from comics to tabletop roleplaying games like Gamma World, and computer games were no exception.

While most computerized role-playing games of the era were rooted in medieval fantasy, a game in development by Interplay Productions sought to bring the gritty, chaotic world of nuclear devastation to home computers. With its lawless setting, brutal combat, and themes of moral ambiguity, the game was a direct response to the dark, anarchic tone of the movies and media that had captured the imaginations of audiences throughout the decade.

During the early to mid-’80s, Interplay Productions, co-founded by Brian Fargo and a small team of developers, had established itself as a key player in the computer gaming industry. After developing early titles such as Demon’s Forge and the critically acclaimed The Bard’s Tale, Fargo recognized the potential for computer role-playing games to evolve beyond the traditional fantasy settings that dominated the genre. He envisioned a game that could bring a sense of realism, choice, and consequence to the genre, moving away from the swords-and-sorcery formula popularized by the likes of Ultima and Wizardry.

Brian Fargo and Interplay developed the highly successful and influential The Bard’s Tale series, which helped define computer role-playing games in the mid-1980s. The first installment, released in 1985, was praised for its advanced graphics, deep mechanics, and engaging first-person dungeon-crawling experience. The series continued with The Bard’s Tale II: The Destiny Knight in 1986 and concluded with The Bard’s Tale III: Thief of Fate, which launched in the spring of 1988. The series became one of the most iconic roleplaying franchises of its era.

While Fargo and his team were solidifying Interplay’s reputation as a premier role-playing game developer, Electronic Arts was emerging as a dominant force in the video game industry. Founded in 1982 by former Apple executive Trip Hawkins, the company had positioned itself as a publisher that nurtured game developers, often crediting them as rock stars of the digital age on game packaging, mirroring the music industry’s approach to recording artists. By 1983, Hawkins’ company was funding and publishing innovative titles, quickly establishing itself as a powerhouse in the industry. The company’s focus on high-quality, polished releases made it an attractive partner for developers like Interplay, who needed financial and distribution support to bring complex, large-scale projects to market.

The team at Interplay shared Fargo’s ambition to push boundaries and had already demonstrated their expertise in crafting engaging role-playing mechanics with The Bard’s Tale. In 1986, with Fargo serving as director and designer, game designers Ken St. Andre and Alan Pavlish began work on Wasteland, a post-nuclear survival role-playing game heavily inspired by Mad Max. Their vision was to create a game that broke free from traditional role-playing games’ rigid, linear storytelling, instead offering players a dynamic, persistent world where choices had lasting consequences. Unlike the static environments of most games at the time, Wasteland would remember the player’s actions, ensuring that decisions, both good and bad, shaped the unfolding narrative. Recognizing the need for a compelling story to match the game’s ambitious design, Interplay brought in acclaimed science fiction and fantasy writer Michael A. Stackpole in 1987. Stackpole, known for his work in both tabletop roleplaying games and novels, was tasked with writing the game’s narrative.

Rather than relying solely on combat experience for character progression, Wasteland introduced an innovative skill-based system that allowed players to develop a wide range of abilities. The approach encouraged creative problem-solving, offering players multiple ways to tackle obstacles beyond brute force.

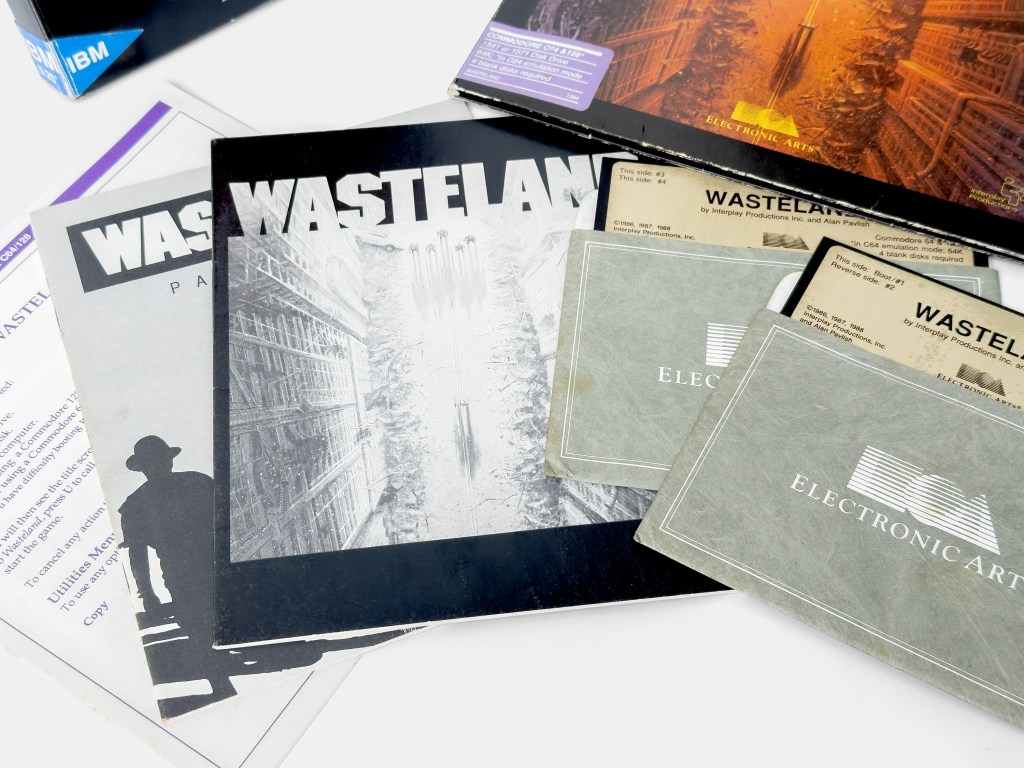

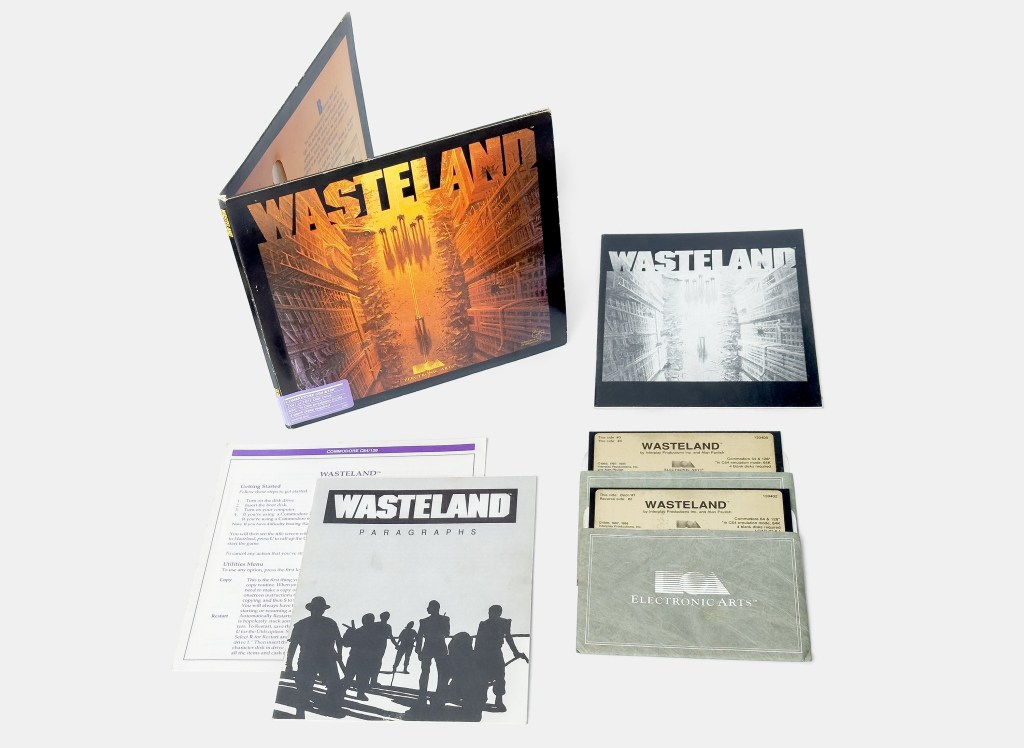

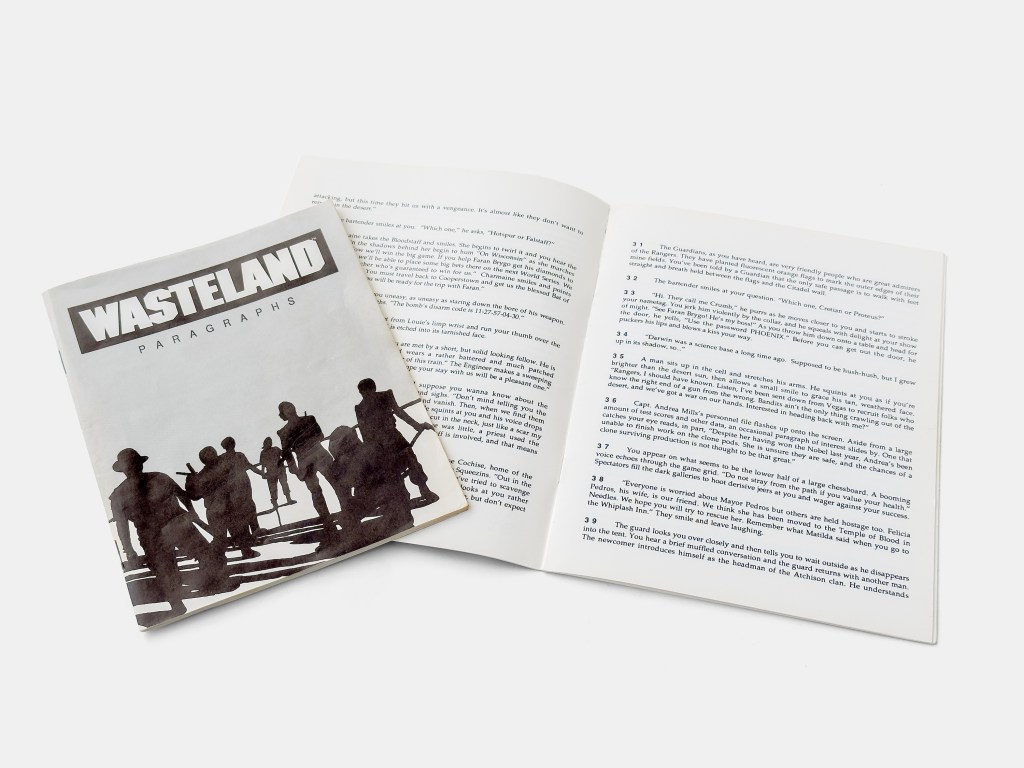

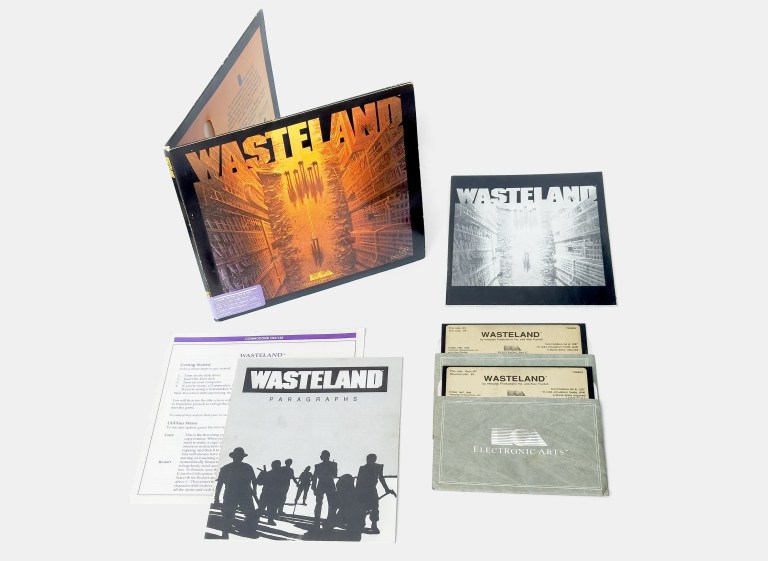

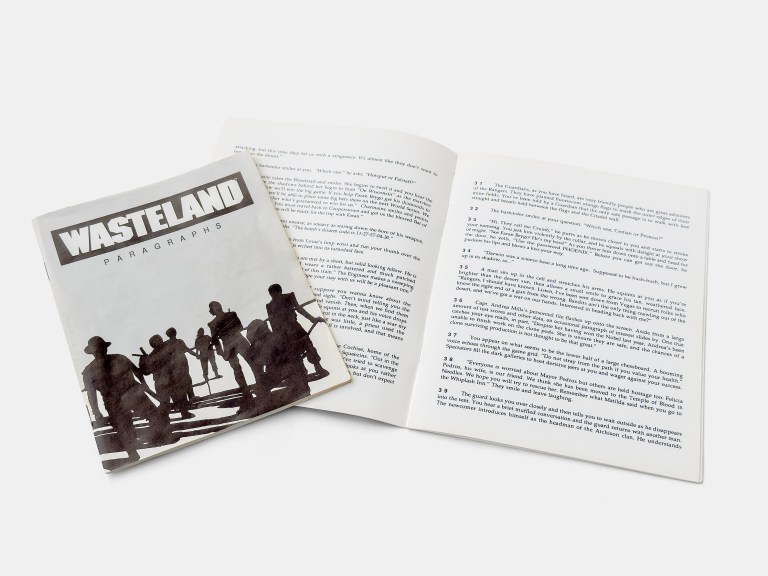

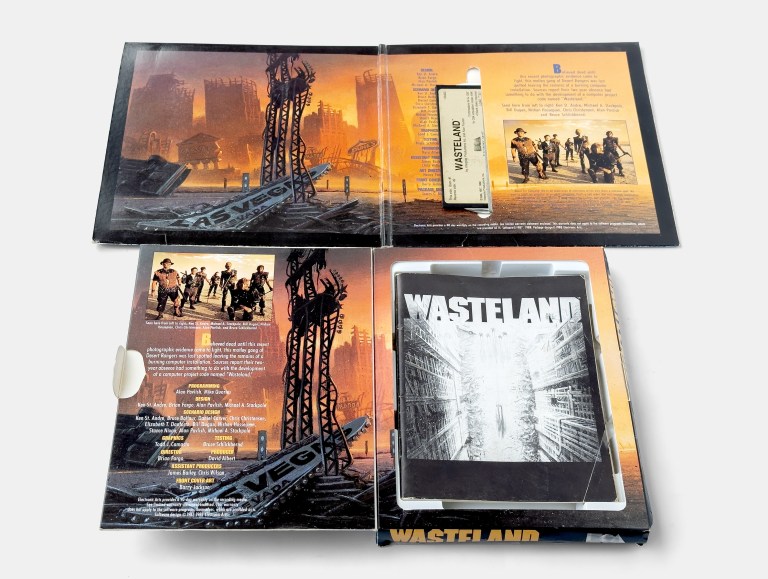

A major innovation was the introduction of non-playable characters, NPCs, with distinct personalities and motivations. Unlike the typical party-based role-playing games where recruited characters functioned as blank slates, Wasteland’s party members had their own behaviors and could even act independently of the player. Instead of relying entirely on in-game text, the game came with a printed 26-page Paragraph book that players referenced when prompted. This allowed for richer storytelling while saving on precious disk space, a necessity in an era where disk space was a scarce commodity. The Paragraph books also served as a rudimentary form of copy protection.

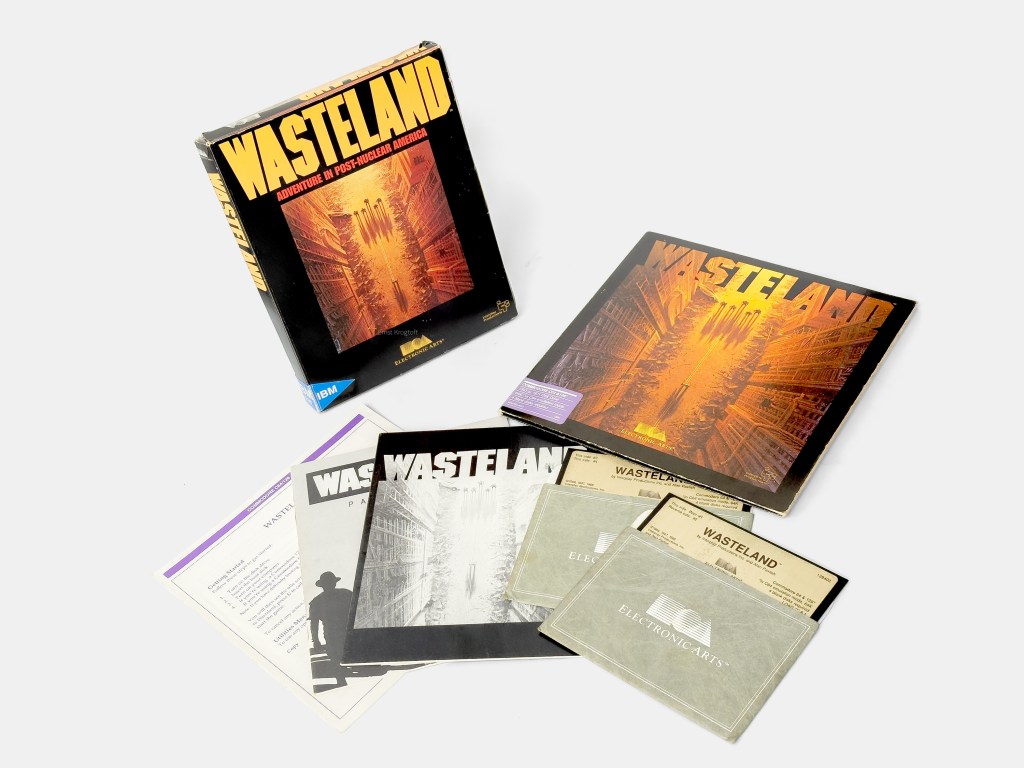

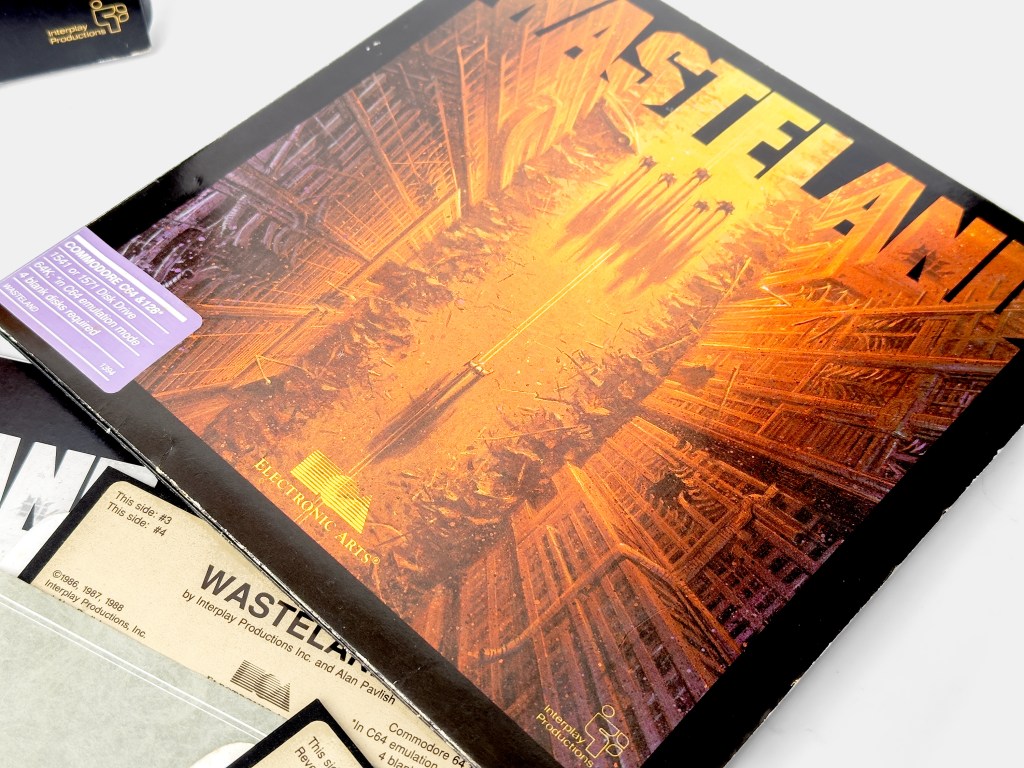

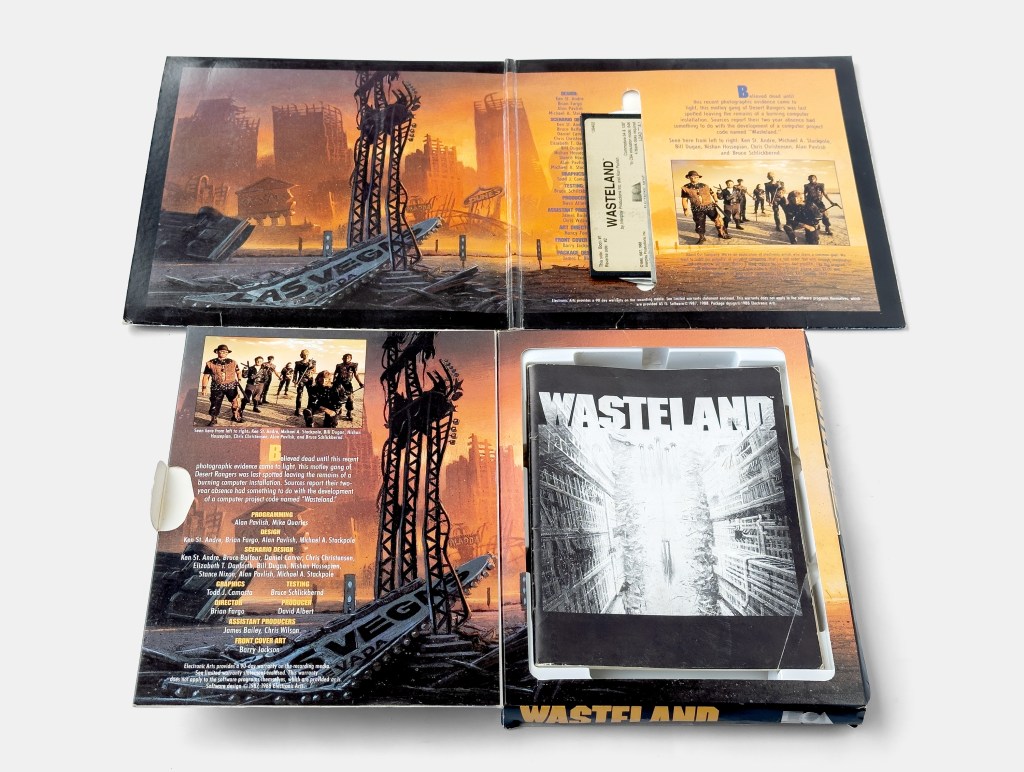

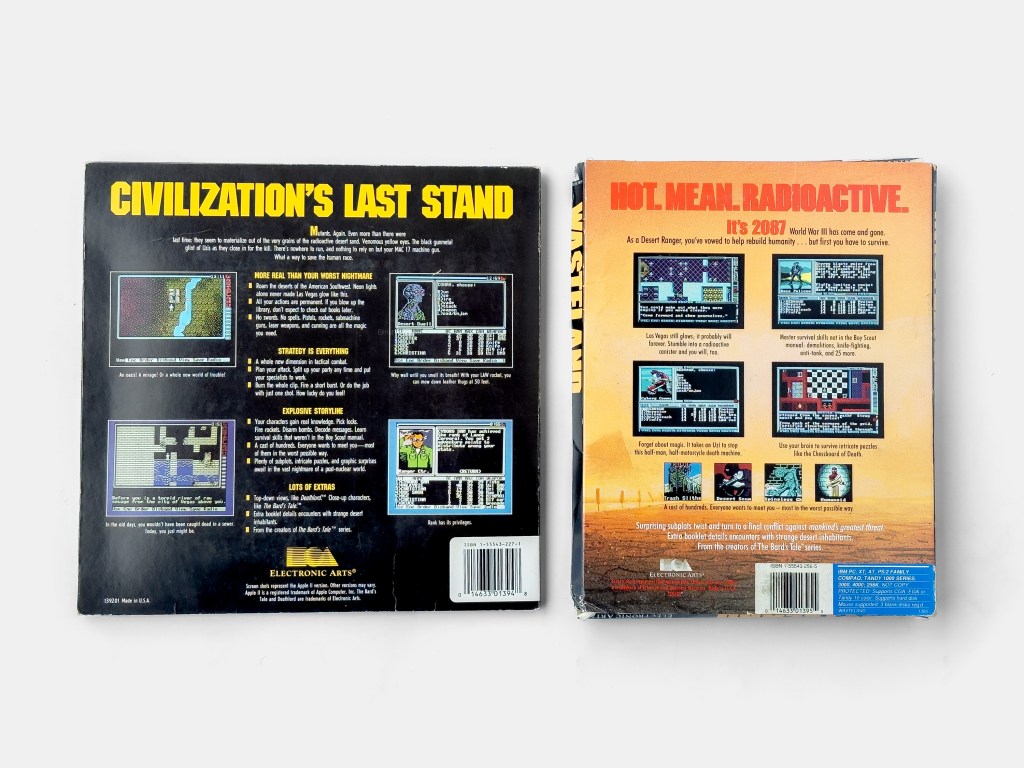

By late 1987, the development of the Apple II version of Wasteland, the platform for which it was originally created, was completed. Final masters were delivered to Electronic Arts, which handled packaging, publishing, marketing, and distribution. The Apple II version was released in the spring of 1988, and work commenced on ports for the Commodore 64 and IBM PC to expand the game’s reach to the most popular home computer systems of the era. Both the Commodore 64 and IBM PC versions were released in late 1988.

Wasteland was initially released for the Apple II in the spring of 1988 with Electronic Arts handling packaging, publishing, marketing, and distribution. A Commodore 64 and IBM PC version was released later that year,

The game shipped on both sides of two write-protected 5.25″ disks. To play, you copied all four disk sides to your own writable floppies and then booted off the copy of disk 1. As you played, the choices made by you, items acquired, characters killed, etc, would be permanently written to the set of disks.

Wasteland’s Paragraph book enhanced the storytelling by providing richer narrative details while conserving disk space.

It also served as a clever form of copy protection, ensuring only legitimate players could access key story elements.

Wasteland is a post-apocalyptic role-playing game where players lead a squad of Desert Rangers through the irradiated ruins of the American Southwest. With a skill-based system, turn-based combat, and a dynamic world where choices have lasting consequences, the game challenges players to navigate moral dilemmas, scavenge for resources, and battle ruthless factions in a quest to restore order to the wasteland.

Following its release, Wasteland became a commercial and critical success. Reviewers praised its depth, open-ended gameplay, and mature storytelling. Computer Gaming World hailed it as one of the most immersive role-playing games ever made, noting how its world felt truly alive compared to the more static environments of contemporary games in the genre. However, it also became infamous for its difficulty. The game did not hold the player’s hand, and making the wrong choices could result in permanent consequences. The brutal design philosophy added to its charm, rewarding careful planning and tactical thinking over brute force. Computer Gaming World named Wasteland “Adventure Game of the Year” in its October 1988 Issue.

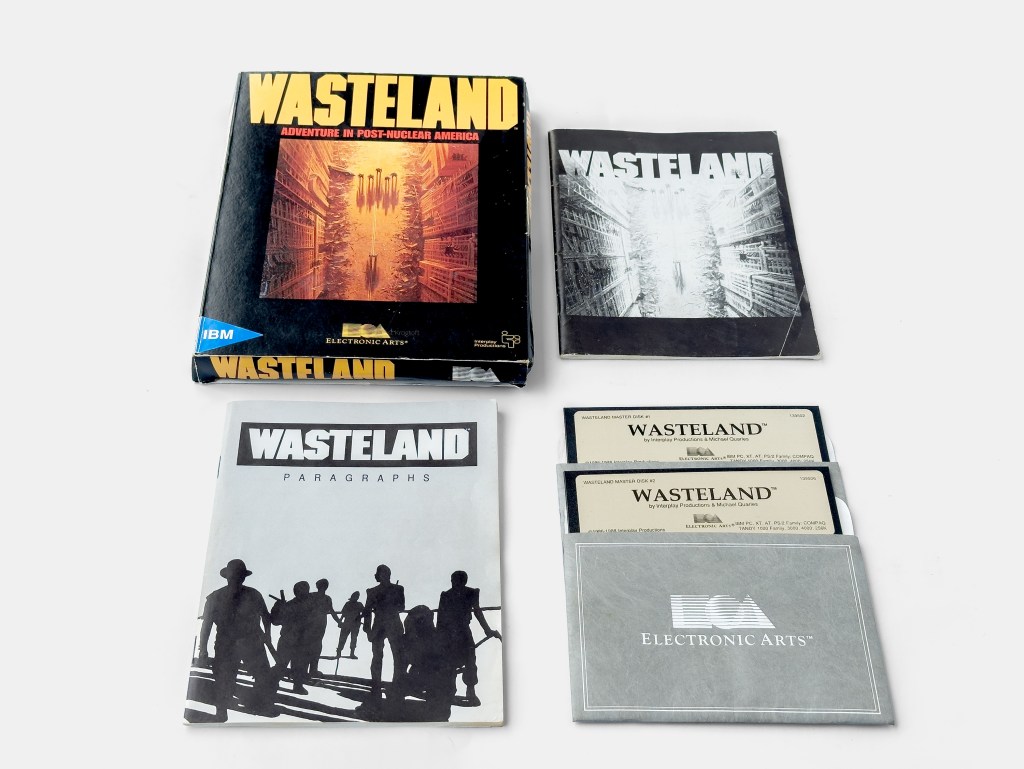

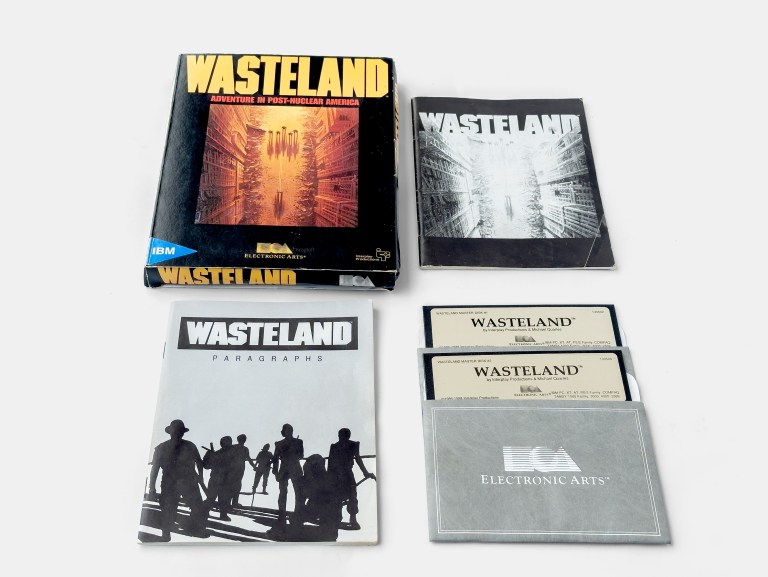

Wasteland was ported to the IBM PC and published by Electronic Arts in December 1988.

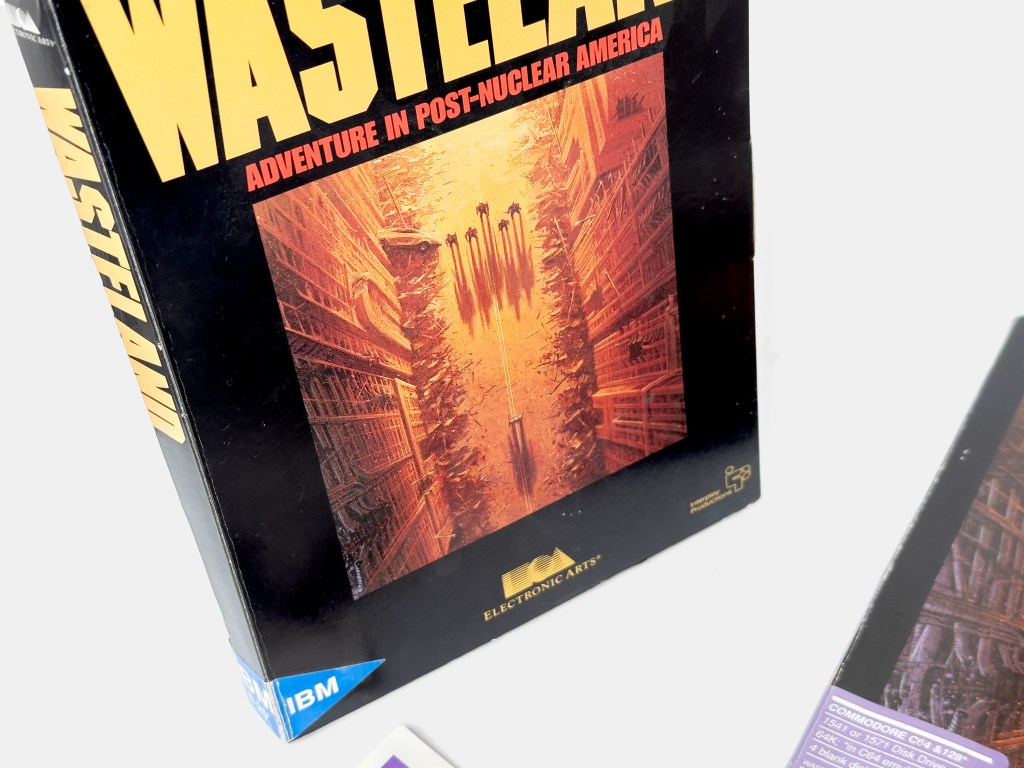

The Album cover packaging used earlier was swapped for a more traditional box.

Designed by James Blair and featuring stunning cover art by Barry Jackson, Wasteland’s packaging perfectly captured the bleak, dystopian atmosphere of a post-nuclear world.

Despite its success, Wasteland never received a direct sequel during its original era. Interplay had originally planned a sequel called Meantime, slated for release in 1989 on the Apple II. The game, which featured a time-traveling premise where players recruited historical figures, was worked on. However, as the Apple II and 8-bit market declined, the project was deemed too costly to port to the IBM PC, leading to its cancellation. A beta version was reportedly produced, but full production was ultimately abandoned.

Wasteland’s influence was undeniable. Many of its core mechanics, moral choices, persistent world changes, and skill-based progression became hallmarks of the role-playing genre. Interplay later attempted to revive the Wasteland name, but Electronic Arts still held the rights to the title. Instead, in 1997, the game evolved into Fallout, a spiritual successor that, while set in a different universe, carried forward Wasteland’s themes and mechanics, developed by many of the same minds behind Wasteland. The Fallout series refined Wasteland’s vision, introducing a broader audience to the grim, irradiated wastelands of post-nuclear survival. The DNA of Wasteland can be seen in countless modern role-playing-like games, from The Outer Worlds to Cyberpunk 2077, each of which owes a debt to Interplay’s pioneering 1988 title.

It wasn’t until 2014 that a proper sequel, Wasteland 2, was finally released. By then, the IP had been acquired by Fargo’s company, inXile Entertainment. Funded through a successful crowdfunding campaign, the game was a love letter to fans of the original, proving that the franchise’s legacy was still alive decades later.