A 1989 title dared to confront the harrowing realities of war, eschewing glorification in favor of a sobering exploration of survival, morality, and human resilience. It stands as a bold departure from the action-centric titles of its time, offering players a raw, emotional journey that challenged conventions and left a lasting legacy.

The Vietnam War remained a subject of deep cultural resonance throughout the 1980s. Its wounds were still fresh enough to haunt those who lived through it but distant enough for a younger audience to explore its complexities through popular culture. Movies like Platoon and Full Metal Jacket strayed away from the bombastic heroics of earlier war stories, focusing instead on war’s psychological toll and moral ambiguity. The narratives struck a chord with a generation still grappling with the war’s legacy, transforming them into compelling, albeit sobering, backdrops for books, movies, and video games.

The video game industry, while trailing movies, was quickly evolving into its own entertainment behemoth. The medium heavily influenced games, and with systems like the Commodore Amiga, it was now possible to deliver an entertainment experience closer to cinema. While most war-themed titles stuck to arcade-style action or grand strategy, a game in the works in the UK during 1989 dared to do something different.

Ian Harling and Simon Cooke of Shadow Development were driven by a shared vision for a groundbreaking project. Harling had long wanted to create a game inspired by the visual sophistication and interactive movie style of Cinemaware titles like Defender of the Crown but with deeper, more emotionally engaging gameplay. Initially, he considered setting the game during the English Civil War. However, the abundance of available material on the Vietnam War, along with its strong resonance in pop culture, prompted him to shift focus and take the first steps toward what would become The Lost Patrol, a concept that blended resource management, survival mechanics, and moral dilemmas with bursts of action.

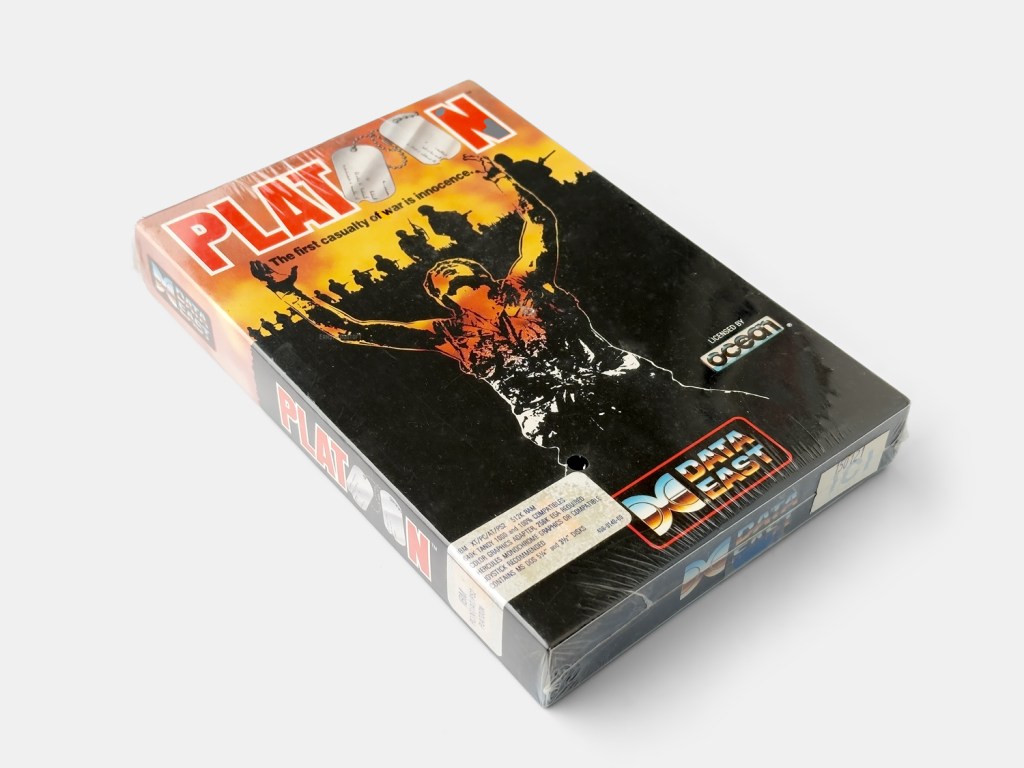

Harling and Cooke worked from their respective homes hundreds of miles apart. Despite the distance, their collaboration thrived, reflecting the era when small, bedroom-based teams still could produce commercially viable games. Harling, primarily a graphic artist, did extensive research, drawing inspiration from war movies, documentaries, and books to ensure authenticity. Cooke, an experienced coder, pushed the Amiga’s capabilities to realize ambitions. After pitching the idea to several companies, UK powerhouse Ocean Software ultimately greenlit the project with the initial intent of a sequel to its 1987 action title Platoon.

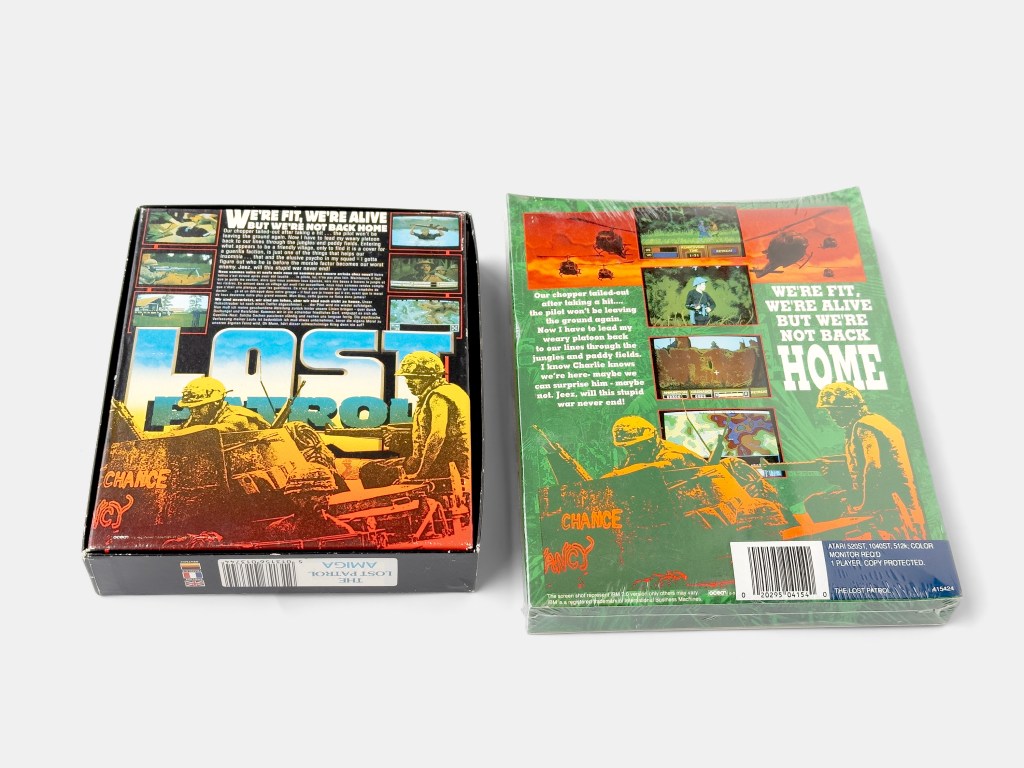

Ocean Software bought into Harling and Cooke’s concept, initially envisioning it as a sequel to their 1987 action title Platoon, seen here in its North American release by Data East.

The development process soon proved to be riddled with challenges. Ocean Software pushed for a more arcade-like structure in line with the company’s other titles, while Harling and Cooke aimed to craft a more realistic experience. The clash in direction resulted in delays and significant compromises. Despite this, Harling and Cooke managed to preserve parts of their core vision for the game.

The game’s visuals, created using Electronic Arts’ Deluxe Paint II, incorporated hand-drawn images, photo references, and digitized footage, created using Rombo Productions Vidi Amiga, a high-resolution video digitizer. Harling spent 12-14 hours a day meticulously crafting each screen while the memorable soundtrack, composed by only 16-year-old Chris Glaister, created an experience that captured the harrowing uncertainty and moral conflict of war.

Amid the wealth of arcade shooters, action, and strategy games, The Lost Patrol, broke new ground, when released around Christmas 1989. The game defied expectations by prioritizing atmosphere and emotional depth over bombastic action. It wove together survival mechanics, tactical decision-making, and a haunting soundtrack, delivering a truly unique gaming experience.

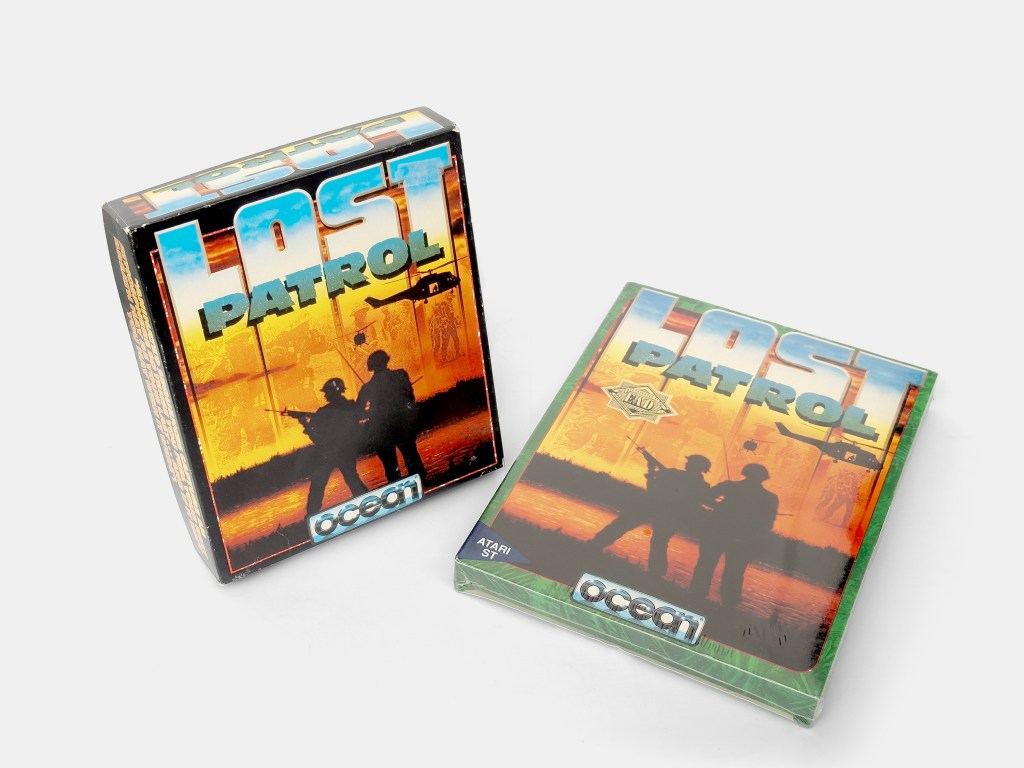

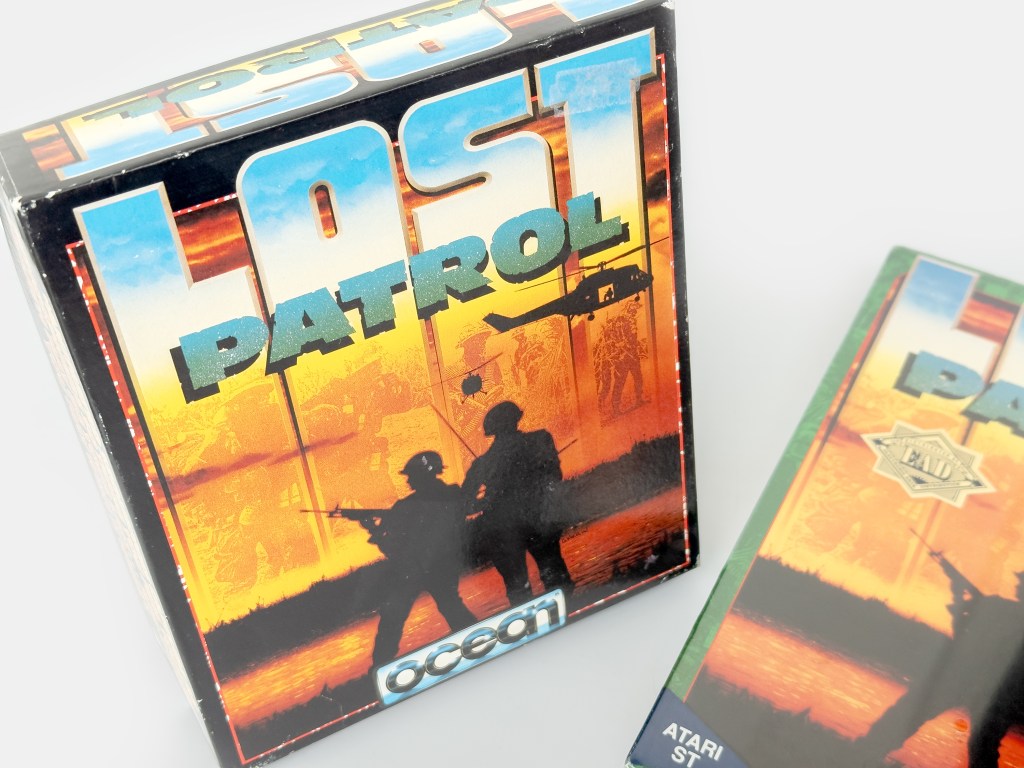

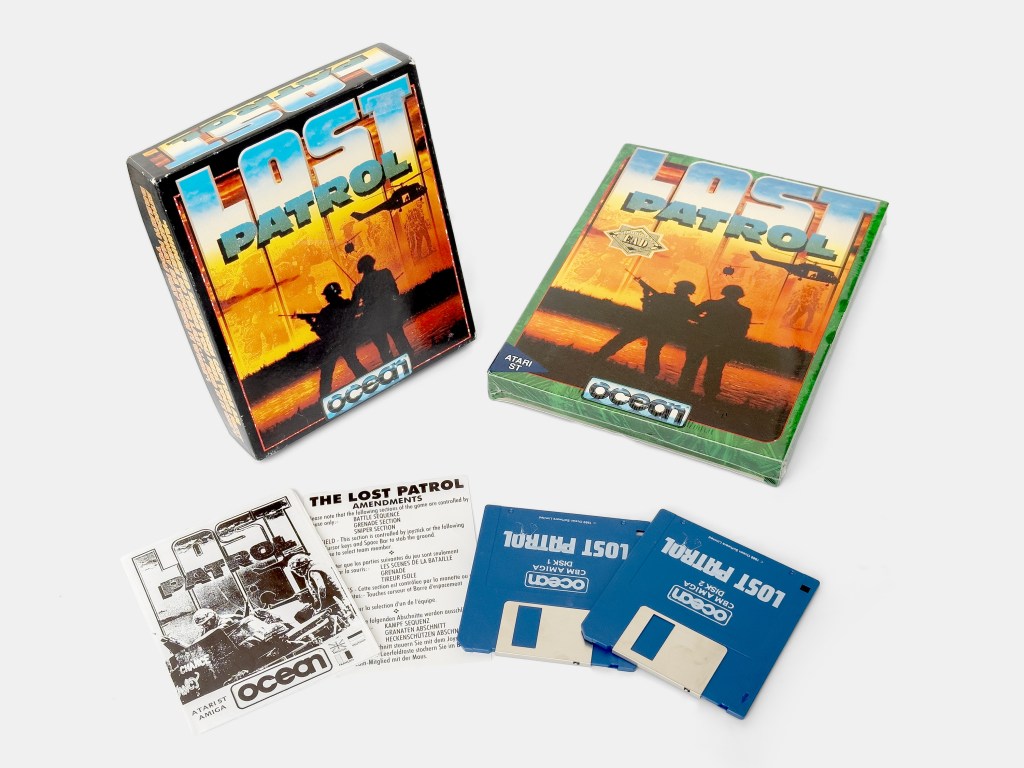

Ian Harling and Simon Cooke’s The Lost Patrol was picked up by UK powerhouse Ocean Software and published for the Commodore Amiga around Christmas 1989. The European release came in the classical small box used by most publishers on the continent while North America received a larger box, distributed by Electronic Arts Distribution.

Set in 1966, the story follows Sergeant Charlie Weaver, tasked with leading his squad of helicopter crash survivors across 58 miles of Vietnam’s perilous Central Highlands to reach the hell hole of Du Hoc. Players face treacherous landscapes, resource management, and ethical dilemmas. Enemy ambushes, booby traps, and minefields add tension, while morale, food, and ammunition must be carefully managed. A poorly timed rest or a reckless decision could spell disaster, and interactions with civilians would carry their own risks and rewards.

Combat is portrayed through a series of varied mini-games, including sequences of hand-to-hand fighting, sniper engagements, and minefield navigation.

In an interview, Harling recalled the meticulous work that went into the project, describing how the duo worked tirelessly to create an authentic and immersive experience. He spoke of the extensive research that informed the game’s visuals and tone, emphasizing their commitment to creating a title that resonated emotionally with players. He also shed light on the difficulties of working with Ocean Software, including the frustrations of having to compromise on key elements of the game’s design. Yet, he expressed pride in what they were able to achieve.

The game faced some post-launch challenges as an early, pirated version of the game plagued by bugs damaged its initial reception. Furthermore, the DOS port from 1991, developed by Astros Productions, suffered from downgraded graphics and stripped-down mechanics. Despite the setbacks, the game sold well, reaching the UK’s Amiga top ten charts in late 1990. Critics praised its innovative gameplay and atmosphere, though some found it somewhat repetitive. Computer Gaming World harshly criticized the DOS version, rating it zero stars for its poor playability.

While the game sold reasonably well, Harling and Cooke suspected they were not fully compensated by Ocean Software, a sentiment echoed by other developers who worked with the publisher at the time.

Harling and Cooke’s vision managed to set the game apart with its unflinching portrayal of the Vietnam War. Abstain from glorification, the game conveys the harrowing realities of conflict, the fragility of life, the weight of leadership, and the pervasive sense of despair. As Roberto Dillon noted in The Golden Age of Video Games, The Lost Patrol offered “a different perspective on war from any other game released before or since … showing there is no glory in war but only pain and destruction.”

The Lost Patrol remains a testament to the ambition of Harling and Cooke and their team. Although Shadow Development disbanded after the game’s release, the title’s legacy endures as a unique exploration of war’s psychological and moral complexities within video games. Reflecting on the experience, Harling expressed both pride and regret, wishing they could have delivered the game as originally envisioned. Today, it stands as a moving reminder of an era when small teams dared to push the boundaries of what video games could achieve… and dared to do things differently.

sources: Matthias Veit’s Interview with Ian Harling, Wikipedia, Lemon Amiga, Amiga Reviews…

This is a really interesting game. I didn’t really “get it” as a kid, but I respected the fact it was doing something different that felt… noteworthy, somehow.

I’m still not entirely sure I “get it” as a game to this day, but I respect it even more nowadays, knowing some of the story behind it.

i remember seeing it first when i still had a C64 and just read (there was a book, and my mother bought me one instead of letting me see the film, deeming it too heavy for a 13-year old kid) Platoon. drool drool drool.

soon i had an Amiga too and Lost Patrol were on disks 21 and 22 ;) in some ways, playing it had been even heavier than watching Platoon. the jungle around proved to be green hell indeed and i never managed to finish the game, but sure _I_ felt finished. exhausted, overcome and turned into a bloodthirsty beast.

very memorable experience, somehow an anti-war statement (Wings left a similar impression – being a strikingly similar game overall indeed) and a masterpiece of artistry, both in vision and sound.

Thanks for sharing, great hearing a bit of your story.

Disk 21 and 22, hehe, I understand:) There was something “clever” built into the game, rendering it impossible to continue from the first part of the map if you had a pirated copy.

thanks for the reply! surprisingly, my copy didn’t have hidden copy protections, but it had a disk error, preventing minefield-passage minigame from loading. but that’s the only one you can avoid, it isn’t obligatory. my best attempt ended just several days worth of movement until reaching the base – something, probably an ambush, had killed my last remaining man (Weaver, obviously) then :(