Joel Billings turned his lifelong passion for war and strategy games into a pioneering venture when he founded Strategic Simulations, Inc. The debut title, Computer Bismarck, became the first historical wargame for home computers, defining a genre and igniting controversy with tabletop giant Avalon Hill, the very company whose games had inspired Billings. This is the story of how one man’s love for wargames helped shape the future of computer strategy gaming.

Operation Rheinübung, launched by the Nazi Kriegsmarine in May 1941, was a daring bid to disrupt the lifeline of Allied supply convoys crossing the North Atlantic. At its heart was the mighty Bismarck, accompanied by the heavy cruiser Prinz Eugen. With a mission to disrupt the critical flow of troops, weapons, and supplies from North America to Britain, their destruction was paramount. A successful German campaign had the potential to sever Britain’s lifeline across the Atlantic and shift the tide of the war.

Proudly named after Otto von Bismarck, the first Reich Chancellor of the German Empire, Bismarck was a marvel of engineering, armed with eight colossal 15-inch guns and protected by thick armor, she was one of the most powerful and feared warships ever built. On the evening of May 19, 1941, Bismarck and her consort slipped from Gotenhafen, heading for the open waters of the North Atlantic. By the time they cleared the Danish Straits, the British Home Fleet was on high alert, mobilizing a relentless pursuit to intercept the German vessels.

The mighty Bismarck as seen from the German heavy cruiser Prinz Eugen in a Norwegian fjord on May 21, 1941, shortly before departing for the Atlantic.

Image from “Die Kriegsmarine“

On May 24, 1941, in the icy expanse of the Denmark Strait between Greenland and Iceland, the British battlecruiser HMS Hood, the pride of the Royal Navy, and the newly commissioned battleship HMS Prince of Wales intercepted Bismarck and Prinz Eugen. The ensuing clash was a brief but devastating exchange of fire. Within minutes, a shell from Bismarck found its mark, detonating an ammunition magazine aboard Hood. In a cataclysmic explosion, the great ship split in two, her wreckage disappearing beneath the waves within seconds, leaving only three survivors.

While Bismarck celebrated she hadn’t escaped unscathed. A shell from the Prince of Wales had pierced one of her fuel bunkers, causing an oil leak. A seemingly minor damage that proved disastrous in the long run, forcing the German battleship to abandon her raiding mission and attempt a desperate dash for the safety of Nazi-occupied France. The Royal Navy, reeling from the loss of Hood, was now consumed with the single objective, to Winston Churchill‘s words, “find and sink the Bismarck“.

The Bismarck, seen from the Prinz Eugen in the morning of 24 May 1941.

Image from “KBismarck.com”.

The chase culminated on May 27, 1941, when Bismarck met her end in the cold, dark waters of the North Atlantic. Crippled by a torpedo strike from the aging Swordfish biplanes of HMS Ark Royal, her port rudder was jammed, leaving her to steam helplessly in a fatal circle. At dawn, four British warships closed in for the kill, unleashing a torrent of firepower. Over 2,800 shells were fired, with more than 400 striking their target. Once a proud symbol of German naval might, Bismarck was reduced to shambles, aflame from stem to stern, her proud and feared silhouette reduced to a smoldering ruin.

By 9:30 a.m., with no hope, the order to abandon ship was given. Below decks, Fregattenkapitän Hans Oels directed the crew to open watertight doors and prepare scuttling charges, determined to deny the British their prize. An hour later, the once-mighty battleship slipped beneath the waves, vanishing into the abyss with 2,107 souls, only 114 survived.

20 years after the dramatic conclusion of Operation Rheinübung, the relentless hunt for Bismarck was immortalized not just in history books but on tabletops. In 1962, Avalon Hill, the era’s leading producer of strategic board games, released Bismarck, a two-player simulation that captured the tension and strategy of tracking the infamous German battleship. Two revisions in the ’70s expanded the experience, adding control of the Prinz Eugen and refining its mechanics without losing its original appeal. Jon Freeman, game designer and co-founder of Automated Simulations (later EPYX), hailed it in The Complete Book of Wargames as “probably the best—and shortest—introductory wargame on the market at the time.” The blend of historical drama, streamlined strategy, and simplicity made Bismarck not just a standout board game, but an ideal candidate to bring wargames into the digital age.

Bismarck, published by Avalon Hill in 1962 is a two-player board wargame in which one player controls the German battleship Bismarck, and the other the British forces hunting for it.

During the ’70s, tabletop gaming thrived with intricate board game simulations of military campaigns, diplomatic negotiations, economic systems, and sports games being released into the market. One of the many captivated by these games was Joel Billings, who from a young age, grew up surrounded by a family deeply entrenched in military history. His father, Robert, had served as an artillery observation officer during the Normandy campaign in World War II. His uncles were veterans of pivotal battlefields, including North Africa, Sicily, and Leyte in the Philippines.

Robert’s fascination with tactics extended well beyond his military service, shaping his civilian life and inspiring the next generation. An English professor by trade, Robert turned his wartime experiences into homemade tabletop games. Using wooden boards for maps and used nuts and bolts as pieces, crafting a crude yet effective system for strategic play. Though these games never left the confines of their home, they brought immense joy to him and his young son.

In 1965, Robert introduced Joel to Avalon Hill’s Tactics II, the first commercially successful tabletop wargame. Seven-year-old Billings spent countless hours recreating battles on the living room floor, with only his family dog to bear witness to his early strategies. Robert eventually lost interest in wargames and Billings lost an opponent. In junior high, he discovered that wargamers were a minority, there was no one to play against. In desperation, he joined the school chess club where he converted a few curious members into fledgling wargamers. Soon Billings started a dedicated club of his own and earned a reputation as a devoted gamer destined for bigger battles. When his family moved and he started high school, he faced the same dilemma again. Undeterred, he turned to play-by-mail wargaming.

In May of 1979, Shortly before heading to business school, a friend introduced Billings to Tandy Corporation‘s TRS-80, one of the most popular and affordable personal computers of the era. As he explored the machine’s potential, he realized that computers could streamline the tedious mechanics of traditional wargames, like calculating combat odds, all while introducing innovative features such as solo play with rudimentary AI-controlled opponents and the realism of “fog of war.”

For Billings, the vision was clear, he wanted to transform wargaming through computers, but the timing presented a dilemma. Was he going to follow through with his plan to attend business school in Chicago, or was he ready to take the leap, postpone it, and start a company, here in Silicon Valley, where he could turn his lifelong passion into a reality? It wasn’t an easy decision, but his dream of creating digital wargames burned too brightly to ignore.

In the summer of 1979, Billings set out to find a programmer to help bring his vision to life. His first attempt, a pitch to an IBM programmer, ended in rejection. The programmer, unfamiliar with wargames, doubted their commercial viability on computers. Undeterred he placed questionnaires in local hobby shops, seeking programmers who shared his passion for wargames. The effort paid off with promising responses from two skilled and dedicated wargamers, John Lyon and Ed Willeger.

Lyon had been struck with polio at the age of 16 and left paralyzed in both legs. After learning to walk with braces and crutches, he returned to school and embraced intellectual pursuits, participating in Chess Club, among others. His academic dedication earned him college scholarships, including one from Abbott Laboratories, and he attended Lake Forest College in 1959, earning a degree in business before pursuing graduate studies in economics. A job with Control Data Corporation brought him west to Sunnyvale, California, where he eventually responded to Billings’ questionnaires.

Throughout that summer, Billings and Lyon worked by night in Billings’ small apartment to create a prototype for what would become Computer Bismarck. Although Lyon had been programming since the 1960s, he had no prior experience with personal computers or the BASIC programming language. Neither he nor Billings owned a computer at the time, but Billings’ job at Amdahl Corporation, a firm specializing in IBM mainframes, proved fortuitous. Through David Cook, head of Amdahl’s homebrew computing club, the pair gained access to a North Star CP/M machine with a simple text-based display.

Lyon handled the bulk of the programming, while Billings concentrated on the game’s design, assisting with data entry and minor coding tasks. Through their collaborative efforts, they managed to turn their shared vision of a computerized wargame into a functioning prototype. With $1,000 from his personal savings, Billings took a leap of faith and founded Strategic Simulations, Inc. The choice to focus on Bismarck was deliberate as Avalon Hill’s board game’s straightforward mechanics suited the limited capabilities of early home computers, and the historical drama made it instantly engaging. The game’s structure drew inspiration from strategy classics like The Fox and the Goose, recreating the high-stakes cat-and-mouse dynamic of evasion and pursuit.

Billings and Lyon originally set their sights on the TRS-80 as the target platform. However, a chance meeting with Apple Computer’s young and ambitious marketing manager, Trip Hawkins, changed the course of development. Introduced via a venture capitalist, Hawkins, a gaming enthusiast with an eye for the rapidly growing potential of home computers, championed the Apple II as the superior choice for games. He pointed out its vibrant color graphics, robust capabilities, and rapidly growing user base, making a compelling case against the somewhat rudimentary TRS-80’s.

Persuaded by Hawkins, Billings bought an Apple II in October 1979. The existing code was adapted to the new platform, and the game’s map, its sole graphical feature, was created using an early paint program. The shift to the Apple II enhanced the game’s presentation and aligned SSI with a platform primed for the next wave of innovation in computer gaming. Billings worked on a five-year business plan and talked to venture capitalists. By December he had raised another $40,000 primarily from family and friends.

While Lyon was programming, Joel studied the rapidly growing video game market. He visited local game stores, networked with industry professionals, and attended a gaming convention in San Francisco, hoping to secure a publisher for Computer Bismarck. His first call was to Avalon Hill, where Tom Shaw, co-designer of the original Bismarck board game and now the company’s vice president, dismissed the idea.

Undeterred, Billings reached out to Automated Simulations, one of the early pioneers in computer games, but also came to a dead end. The lukewarm responses led to a realization, that if Computer Bismarck was going to see the light of day, SSI would have to publish it independently. In December 1979, Billings brought his sister Susan on board to handle the administrative and logistical side of the business. She came from hospital management in southern California and though she had little interest in games or computers, her organizational expertise and commitment proved just as crucial to SSI’s success as Billings’ passion for strategy. Susan helped foster a collaborative, welcoming work environment that balanced professionalism with a sense of camaraderie, shaping the company’s culture in its formative years.

As Computer Bismarck neared completion, Billings shifted focus to its presentation. In an era when most computer games came in simple zip-lock bags with a floppy disk and a photocopied manual, he envisioned something far more polished. Drawing inspiration from the professional packaging of the board games he had long admired, Billings sought a graphic designer to craft eye-catching cover art. that would signal SSI’s ambition and quality from first impression. He connected with aspiring graphic designer Louis Saekow through an officemate at Amdahl. Just two months earlier, Saekow had made the bold decision to defer medical school to pursue his passion for design. Eager to prove himself, he offered Billings an unusual guarantee, if his work didn’t meet expectations, Billings wouldn’t have to pay him.

Using a large-format stationary camera covertly accessed after hours, thanks to a roommate who worked at a magazine company, Saekow created the striking cover art depicting the mighty Bismarck charging head-on at full speed. To complete the professional presentation, Saekow’s cousin handled the printing of the packaging. The result was a large, board game-style box designed to catch the eye of traditional wargamers who might otherwise dismiss the promising world of computer games.

By January 1980, Computer Bismarck was finished, and Billings launched a grassroots marketing campaign while still operating out of his second-floor apartment. Apple’s warranty list, provided by Hawkins, gave him access to 30,000 potential customers for direct mailers. Soon, 2,000 copies of the game were stacked from floor to ceiling in his bedroom. The game debuted at the Applefest exposition the following month, drawing attention from attendees. To further promote the game, a full-page advertisement ran in the March 1980 issue of BYTE magazine, emphasizing Computer Bismarck’s innovative features such as the possibility to save, play solo against the computer’s AI opponent, or head-to-head competition with another player. The ad also teased upcoming support for the TRS-80 and other platforms.

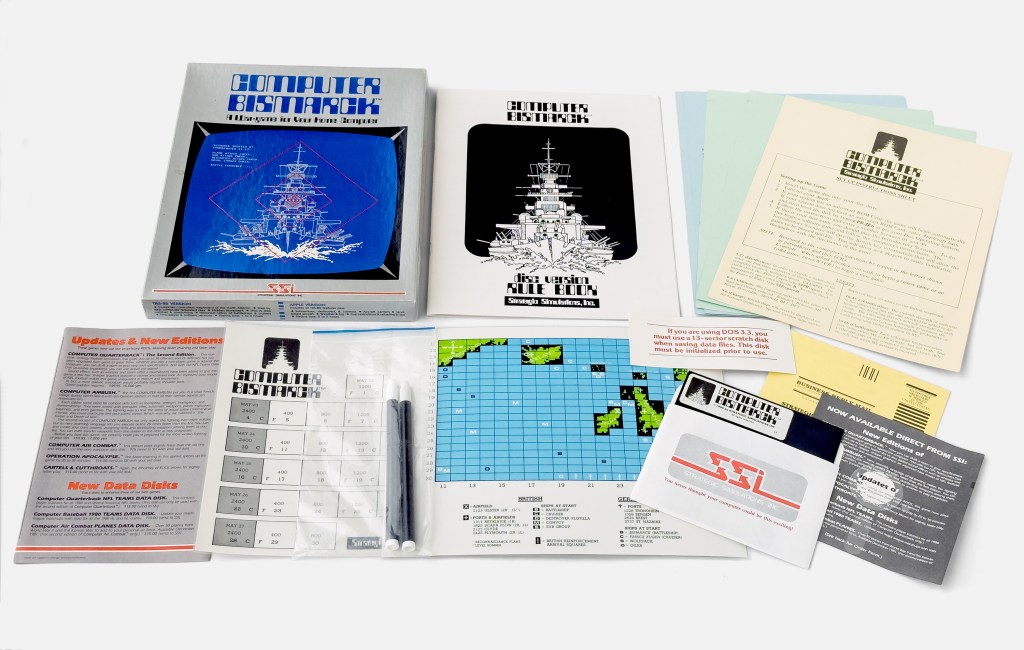

Computer Bismarck, published for the Apple II in 1980 by Joel Billings’ newly founded Strategic Simulations, Inc., debuted in an impressive thick box reminiscent of the board games that inspired it. The distinctive packaging was exclusive to Computer Bismarck and SSI’s follow-up title, Computer Ambush. Inside, buyers found a professionally typeset manual, detailed maps, and pens for marking positions.

Computer Bismarck recreates the dramatic Bismarck Chase in the North Atlantic in May of 1941. The game offers both single-player and two-player modes. In single-player mode, the computer opponent, cheekily named Otto von Computer, commands the German ship and U-boat wolfpacks, while the player leads the British Home Fleet. The action unfolds on a map of the North Atlantic, where military units and facilities like airfields and ports are represented by letters. Players issue orders during alternating phases to maneuver their units, engage in battles, and track status updates. Weather and each unit’s distinct capabilities, including mobility, firepower, and vulnerability, influence the gameplay and outcome of battles.

The second release of Computer Bismarck introduced a slimmer box design, establishing the standard size for SSI packaging in the years to come. Strategic Simulations, Inc. was shortened to SSI on the cover and the floppy came with a branded sleeve.

In 1981, Computer Bismarck was updated, now taking advantaged of SSI’s proprietary RDOS, an operating system with only a small memory footprint allowing for faster load and calculation times. The logotype on the cover was changed from red and blue to red and white.

SSI’s first sales came through Hawkins’ connections, with Los Altos Computerland and Local San Antonio Hobby placing early orders in February 1980. The same month, Lyon quit his secure day job and became fully committed to SSI. Priced at a premium of $59.95 (about $230 today), Computer Bismarck quickly gained traction. Despite its unconventional, oversized packaging for a computer game, stores had no hesitation in stocking it. While Billings originally planned for the majority of sales as mail-order, by March 1980, store orders accounted for 90% of sales. SSI expanded and moved into an office building on San Antonio Road in Silicon Valley.

By October 1980, Computer Bismarck had sold 2,500 copies, an impressive feat for a niche product. SSI’s cheeky magazine ad tagline, “The $2160 Wargame!”, emphasized the combined cost of the game and the Apple II+ system required to play it, generating buzz among wargaming enthusiasts. Over its lifetime, the game sold 7,900 copies and remained available for years, even appearing in SSI’s Fall ’86/Winter ’87 catalog as part of the SSI Classics lineup, priced at $14.95.

The iconic “$2,160 Wargame” ad from 1980, published in Strategy & Tactics magazine, a bi-monthly publication, distributed to subscribers and sold in specialty game shops and newsstands worldwide. The ad cleverly highlighted the combined cost of Computer Bismarck and the Apple II+ system required to play it.

Image from BoardGameGeek.

By the autumn of 1980, SSI began to diversify its catalog with Computer Quarterback, a pioneering football simulation by Dan Bunten. The game’s innovative use of paddle controllers on the Apple II and its overall polish surpassed SSI’s early in-house efforts. Recognizing its potential, Billings struck a deal to publish it in September 1980, making it SSI’s first externally developed title. The game quickly became the company’s fastest-selling product, prompting Billings to reconsider the company’s initial focus on internally developed wargames.

Just six months after Computer Bismarck debuted, Avalon Hill, Billings’s former inspiration and now emerging competitor, entered the computer game market. Borrowing SSI’s naming conventions, Avalon Hill released titles like Computer Diplomacy and Computer Football Strategy. Its first offerings also included a Bismarck-themed game, North Atlantic Convoy Raider.

Computer Bismarck and other titles by SSI clearly copied, or at least lend much of their mechanics from Avalon Hill’s board games. In 1983, Avalon Hill filed a lawsuit against SSI, alleging trademark and copyright infringement. The case was settled out of court, with SSI agreeing to pay $30,000 and a 5% royalty on future sales of Computer Bismarck. By then, however, the game’s relevance had faded, and the lawsuit did little to slow SSI’s growth. SSI solidified its dominance in computer wargaming, while Avalon Hill struggled to replicate its innovation and commercial success.

Computer Bismarck, the first historical wargame marked a turning point for the wargaming hobby, showcasing how computers could transform strategy games with innovations like solo play and advanced simulation features. For Billings, the game represented both the fulfillment of a lifelong passion and the dawn of a new era in gaming. Its success, along with similar titles, marked a shift in the wargaming landscape, as computer wargames began to eclipse their tabletop counterparts. The future of strategy gaming had arrived, heralded by SSI.

On October 15, 2021, John Lyon passed away at the age of 81.

Sources: The Digital Antiquarian, CHEGheads Blog – Jon-Paul C. Dyson, Wikipedia, Computer Gaming World, Softalk, Antic, Sorcerers & Soldiers: Computer Wargames, Retro Gamer, SSI Games Catalog 1990, Legacy…

One thought on “Computer Bismarck, the “$2,160” war game, that launched SSI and brought war games into the digital age”