A fascinating and technologically impressive program invited us all to take a peek at the pixelated little people living inside our computers. The simulation brought a new kind of companionship to life with one of the first true digital roommates and inspired one of gaming’s most popular titles.

How exactly does a computer work? Ask any techie, and you’ll likely get a breakdown of electrical pulses, binary states, zeros, and ones translating into letters, numbers, and beyond, all neatly processed and output. But ask a 6-year-old, and you might get a more imaginative answer: Inside the computer, there are little people, living tiny lives, keeping the digital gears turning, waiting for you to interact and help out whenever you need it.

This whimsical concept is what Little Computer People, released by Activision in 1985, brought to life. Imagine booting up your computer and finding a little person living inside, a digital roommate going about their day, sometimes dancing, reading, or maybe feeding their tiny dog. This “Little Computer Person” wasn’t just standing by for your commands but appeared to have an independent life of their own.

The origins of Little Computer People trace back to programmer, composer, cartoonist, and researcher Rich Gold, who envisioned a digital “Pet Person” in the spirit of the Pet Rock fad of the 1970s, where people inexplicably began “adopting” rocks and treating them like pets. Gold’s idea was a program that would simulate a tiny character living inside one’s computer, a charming figure the user could simply observe. Securing some funding, Gold brought in James Wickstead Design Associates, a product design and development company, based in Cedar Knolls, New Jersey, to develop the concept further. The team worked for nearly a year, refining the idea of a digital house and a virtual “Pet Person”.

Despite the concept’s novelty, Gold initially struggled to find a publisher willing to take on what was, at the time, essentially a screensaver that could be booted up to observe the character’s daily routines. When he approached Activision and met with company president Jim Levy, Levy saw enough potential to consult Pitfall! and Ghostbusters creator David Crane.

Activision was among the biggest names in video games, and Crane saw the concept as ripe for interactivity, a direction that would push the project beyond the original idea. Crane and co-producer/designer Sam Nelson wanted to make the experience dynamic and interactive, a vision that clashed with Gold’s more passive, observational concept. Ultimately, Crane’s approach won out, turning the concept into an interactive authentic, and personal simulation that allowed players not only to “adopt” a digital character with a mind of its own but also peer into its charming, pixelated life.

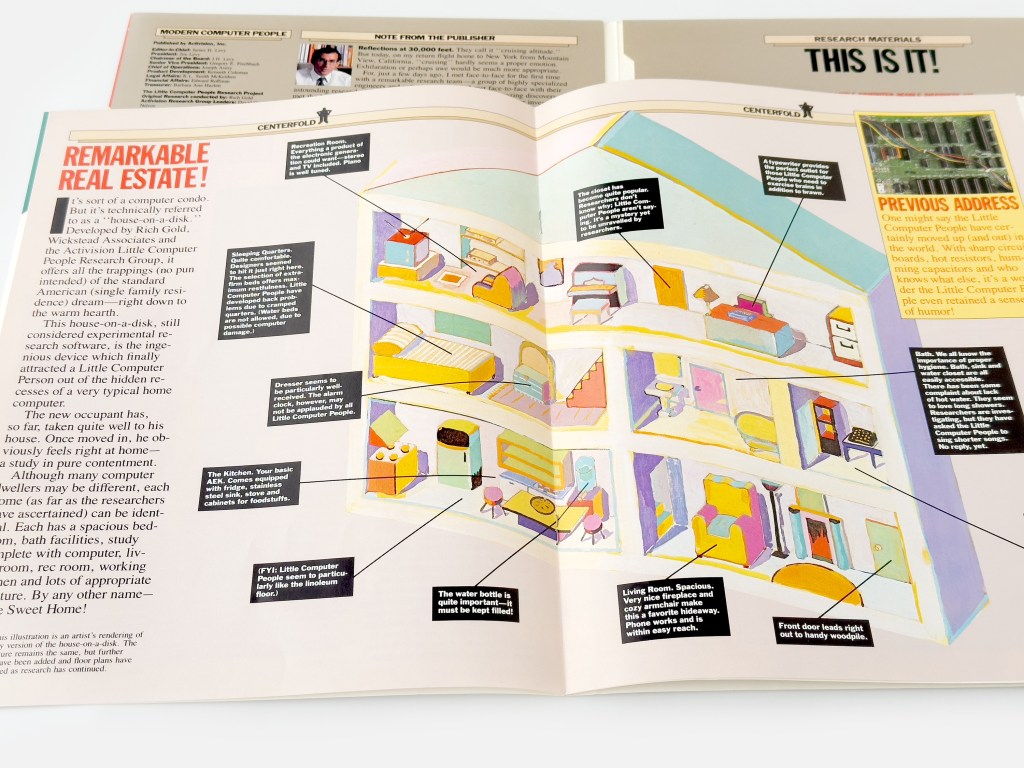

The game’s setup was simple, but its charm lay in its unique approach as there were no objectives or winning conditions. Instead, players saw a side view of a cozy, two-and-a-half-story house where, after a brief wait, a tiny animated character would “move in” and begin a new life. The little inhabitant, a male character generated uniquely for each game, settled in by performing daily routines like cooking, watching TV, reading, etc.

You interact with him through commands and a text parser that recognizes around 160 words. Beyond simple commands, your Little Computer Person can play games with you, like anagrams and poker, adding a social touch to the simulation. One of the most charming features is how your digital housemate occasionally sits down at their typewriter to pen a letter, sharing weekly updates on their mood and needs. These notes feel surprisingly personal. They might tell you if they’re feeling cheerful or down, or politely ask for a new book or fresh clothes, which you can “order” for them via commands and the parser.

An interesting aspect was how each copy of Little Computer People generated a unique character based on a special and unique serial number embedded in an unused sector of the floppy disk, added at the disk duplication facility. The number shaped the little person’s personality, appearance, and behavior, ensuring no two players had the exact same experience. Some were more reserved, others more playful, but all had their quirks and preferences, which added a sense of individuality.

To keep your Little Computer Person consistent with its original character traits and other vital information, the program needed to save data to the floppy disk, ensuring these details loaded seamlessly whenever the Commodore 64 rebooted. Since writing to the disk temporarily made the on-screen character sprite disappear, potentially alarming anyone attached to their virtual roommate, the program would save only when the Little Person slipped behind the closed door of the bathroom, cleverly hiding the sprite and preserving the illusion of an uninterrupted life.

The game had two versions for the Commodore 64, the full-featured floppy disk version and a significantly limited cassette version. On the floppy, the character was persistent, remembered interactions, and had a “moving in” sequence, giving players the sense of seeing their little friend truly “settling in.” The tape version, however, was more rudimentary. Every time it loaded, the character would be generated from scratch, forgetting past interactions and missing features like poker, making it feel more like a glimpse into what Little Computer People could offer rather than the full experience.

Released for the Commodore 64 in September of 1985, with a version for the Apple II arriving later in the year, Little Computer People is often hailed as the first true “life simulator,” arriving nearly two decades before The Sims.

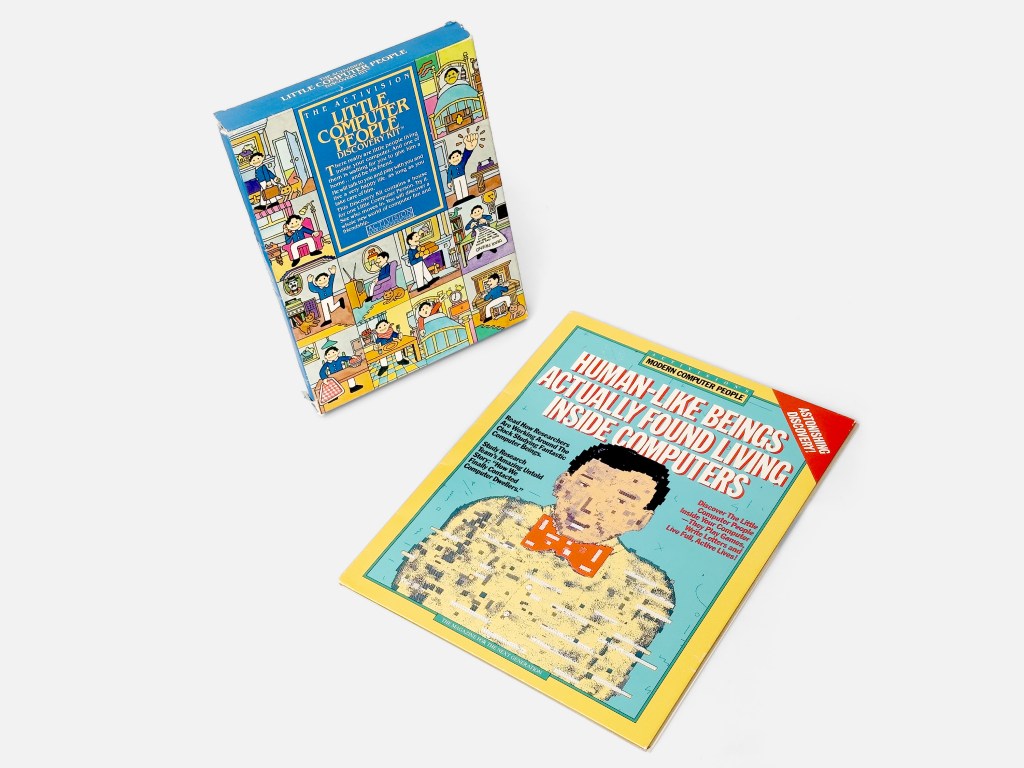

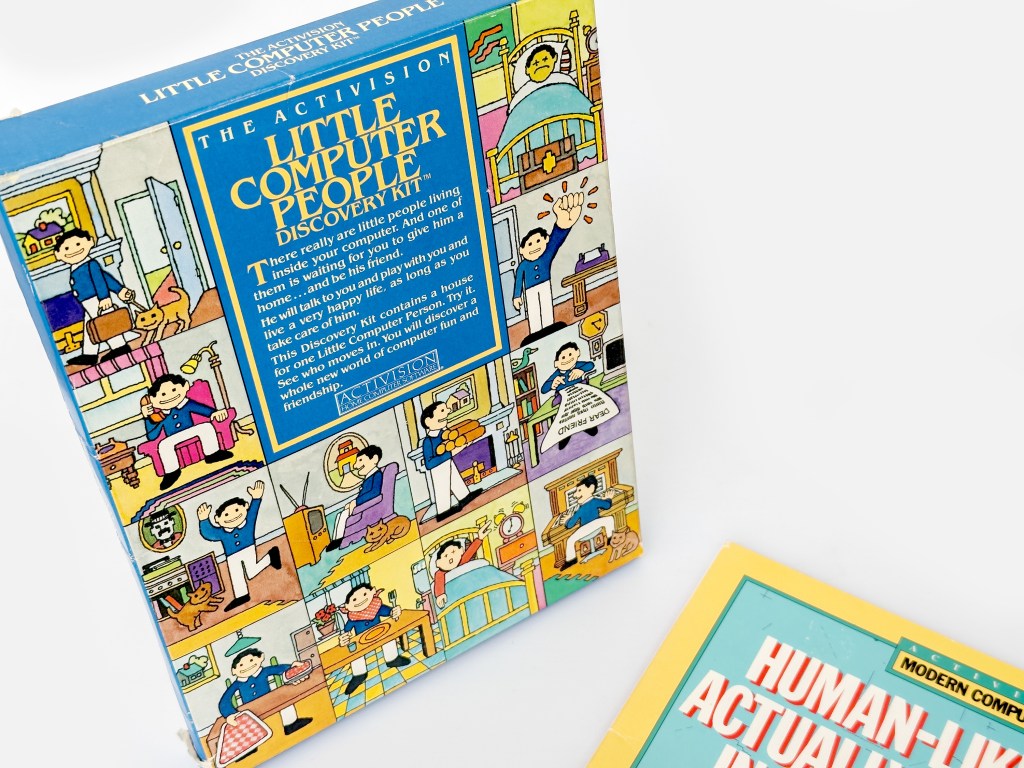

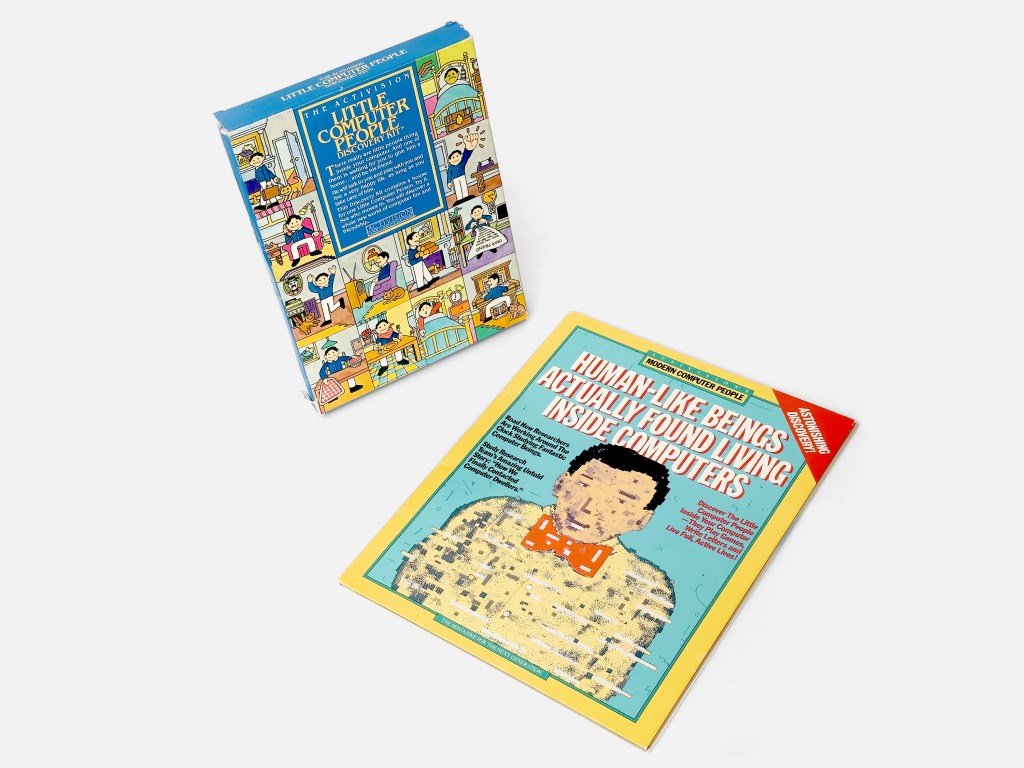

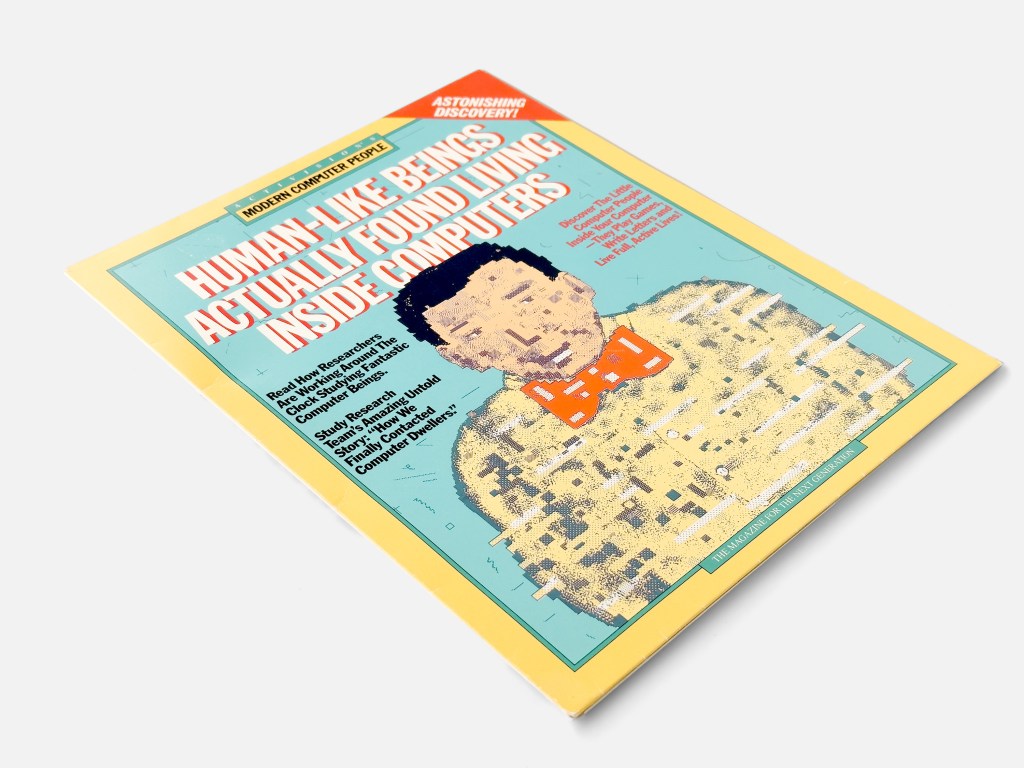

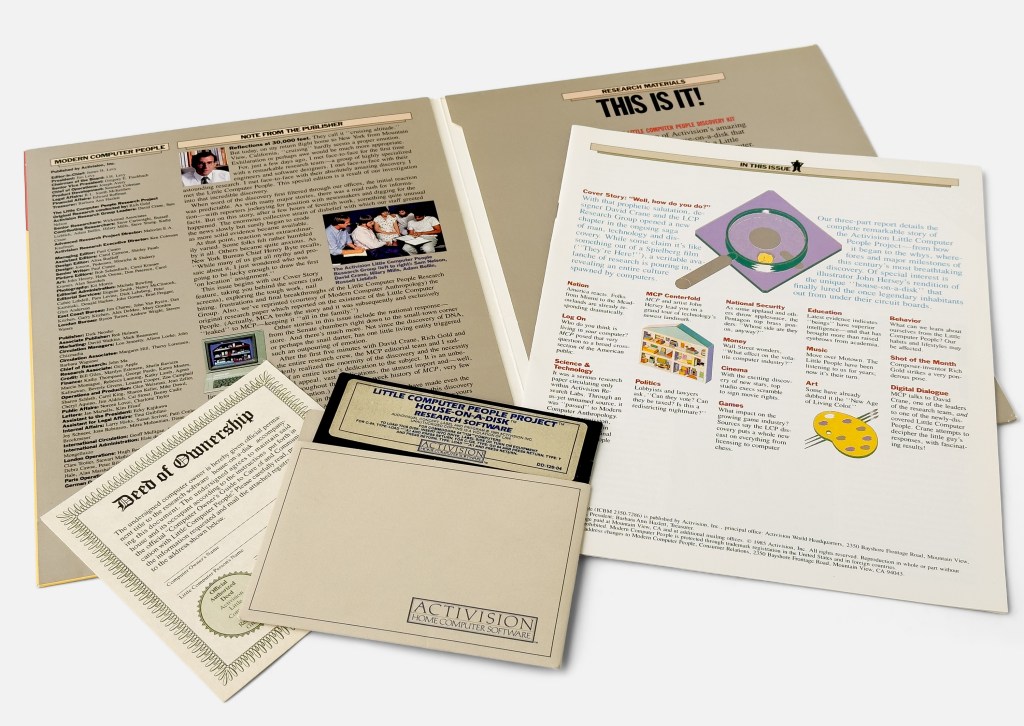

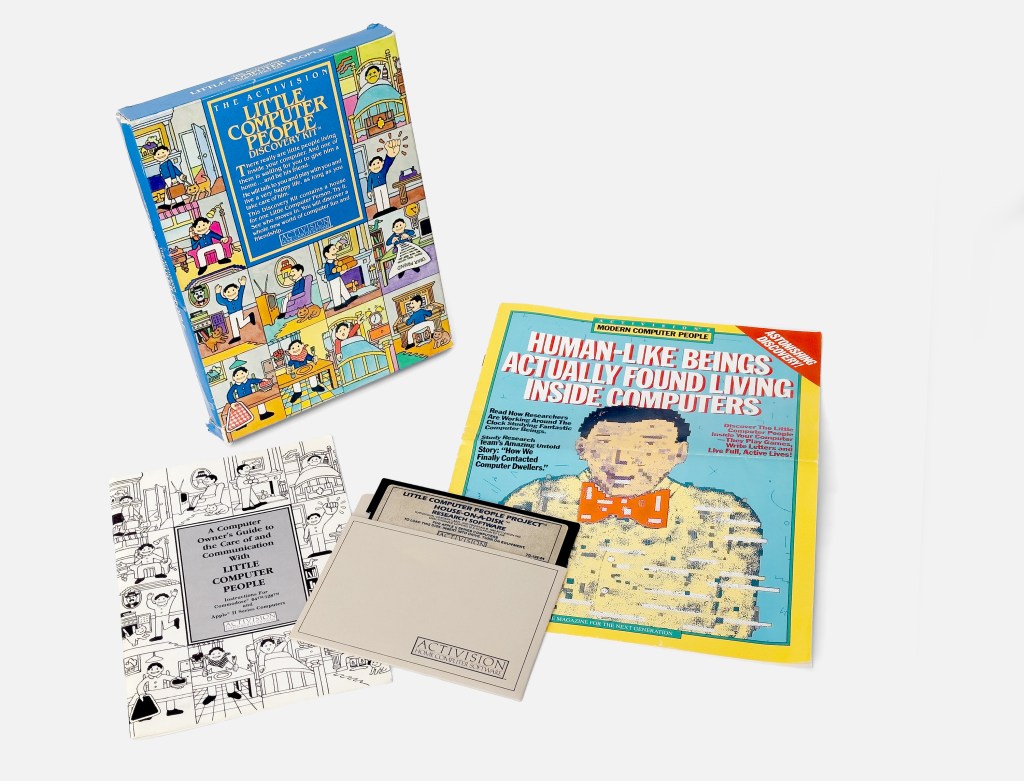

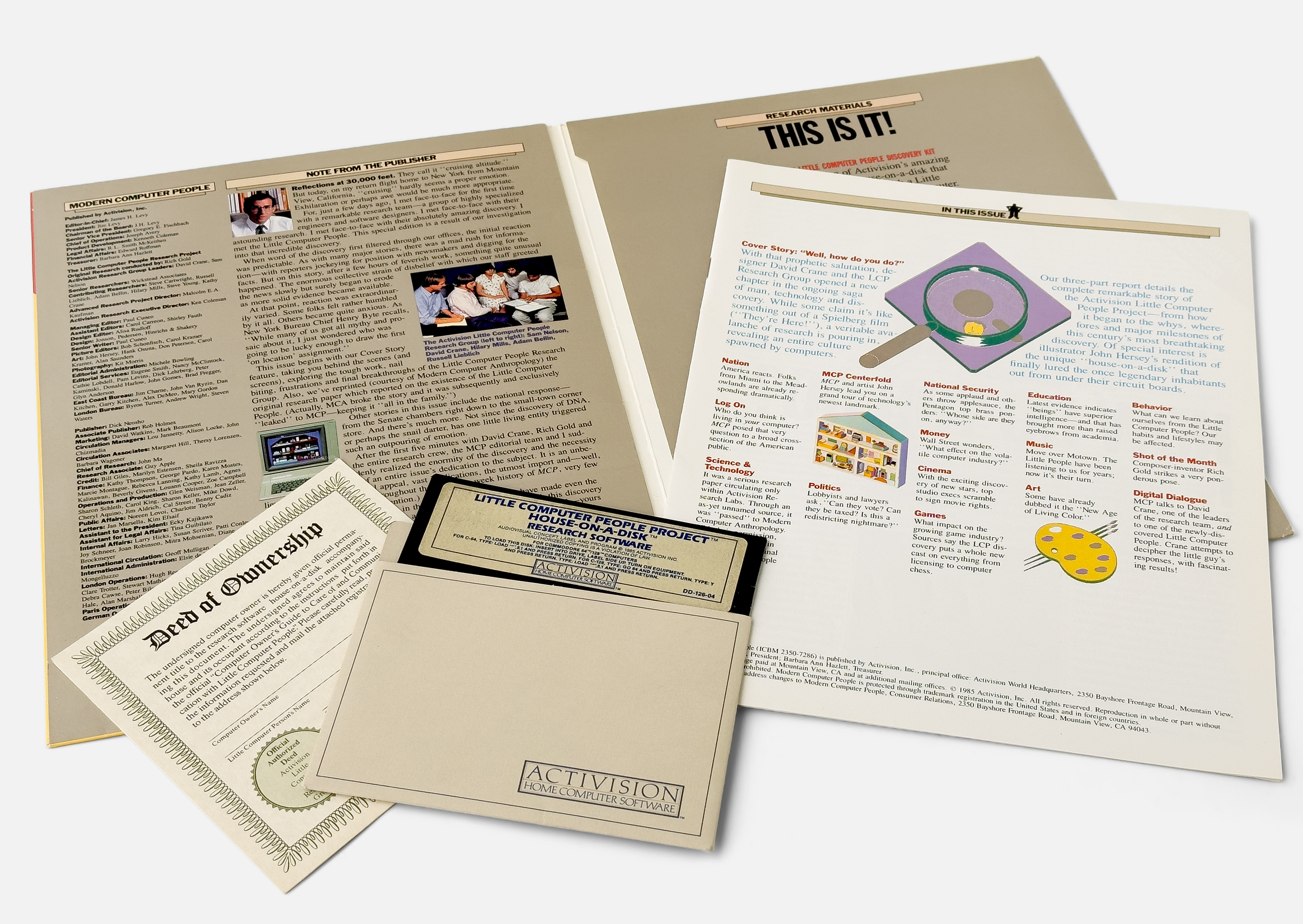

The original release came with packaging that intriguingly lacked the game’s title and was presented as a magazine, titled Activision’s Modern Computer People, with the captivating headline “Human-Like Beings Actually Found Living Inside Computers.” A creative approach that added a bit of mystique to the game’s already whimsical and novel premise.

The original North American floppy disk version for the Commodore 64 was packaged and designed like a scientific magazine, detailing the ‘groundbreaking research’ that uncovered the existence of Little Computer People living inside our computers.

The content included your own deed to your “House-on-a-Disk”.

This was no game in the traditional sense, there were no points, levels, or villains to battle. Instead, Little Computer People offered players the experience of companionship with a quirky little digital soul who, in some parallel universe, might actually be the one keeping your computer running.

Little Computer People lets you observe the digital home, soon to be occupied by a curious Little Computer Person. Starting with an empty house, a small character arrives, inspects the rooms, then returns with a few belongings and a cheerful pet dog. From there, he settles in, cooks, watches TV, listens to music, and even writes letters to share his thoughts. You can interact by sending commands, providing food, playing games, etc… Occasionally, he’ll take the initiative, inviting you to interact.

The game doesn’t need to be running to simulate time, but you’re responsible for your Little Computer Person’s well-being. If he meets an unfortunate end, Activision offered a unique service: where you could mail in your disk, free of charge, and they would revive him, sending back the disk with a fresh chance at digital life.

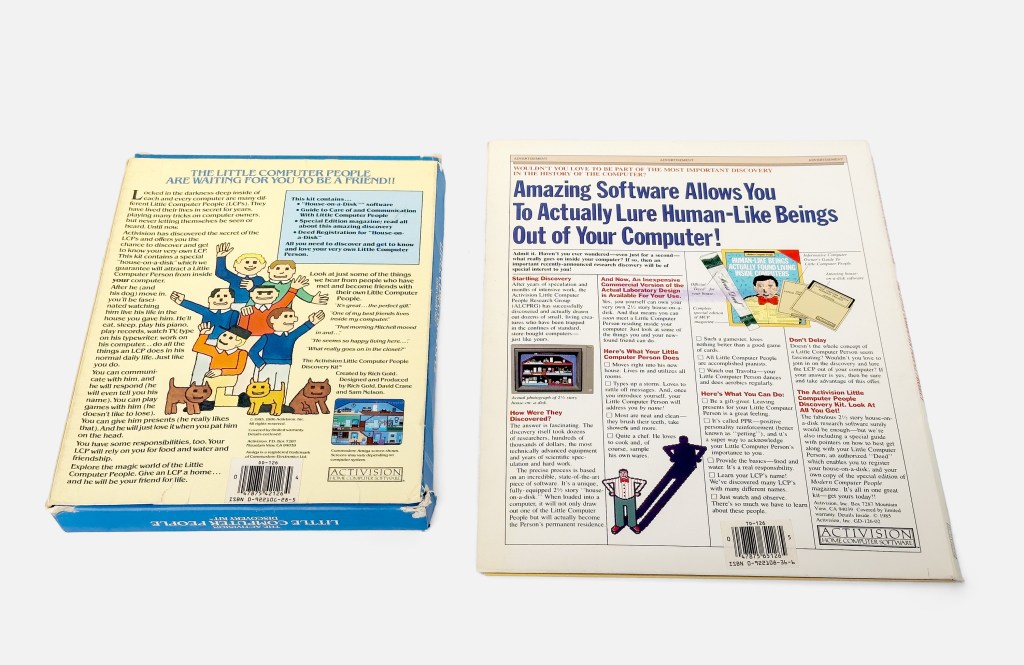

The game’s documentation stayed fully committed to the whimsical pretense that ‘Little Computer People’ were real inhabitants living inside your computer, eagerly awaiting to meet and interact with you.

Little Computer People was rereleased for the Commodore 64 and Apple II in 1986, boxed and titled “The Activision Little Computer People Discovery Kit”.

The Apple II version was created by Wickstead Associates, without the involvement of David Crane.

Little Computer People found its way to other platforms in 1987, including the Atari ST, and Amiga, where the overall experience remained consistent, though with graphical enhancements on the more powerful machines. Reviews at the time were mixed but generally positive with many praising the game’s originality and concept. Others expressed disappointment over the lack of defined goals and its replay value in the long run but admired its technical ambition. Compute! magazine commended it for its charm, suggesting it could be a “friend inside your computer.”

While the game was more of a curiosity and didn’t have the lasting commercial success Activision might have hoped for, it inspired countless players to view computers not simply as machines, but as places where unique digital personalities could thrive, just waiting for someone to press play and say hello. It left a lasting legacy, influencing future life-simulation games like The Sims, Tamagotchi, and Animal Crossing, which took the open-ended, interaction-based approach of Little Computer People to new heights. Though commercial success eluded it, the game gave players a taste of companionship in a digital world, a theme that has only grown stronger as life simulators and our digital world have evolved.

Will Wright, designer of The Sims stated that playing Little Computer People and talking to Rich Gold helped him develop concepts for The Sims, one of the best-selling video game series of all time, with over 200 million sold copies.

Sources: Wikipedia, zzap64! magazine, Jaruzel.com, The Famous Computer Cafe w/Andy Velcoff- KIEV 870 AM Jan 2, 1986…

2 thoughts on “Little Computer People, When Digital Life Came to Life”