Throughout gaming history, developers have woven weird and wonderful Easter eggs into their software, just waiting to be uncovered by curious minds. Some are found quickly, while others lie hidden for decades, gathering mystique until a dedicated fan or digital archaeologist finally cracks the code. Gumball is one such game—a quirky, challenging title from the early ’80s that hid an intricate cipher, buried deep within its colorful gumball-sorting mechanics. Released by Brøderbund and designed by Robert Cook, Gumball wasn’t a massive hit, but its secrets captured the attention of hackers and enthusiasts.

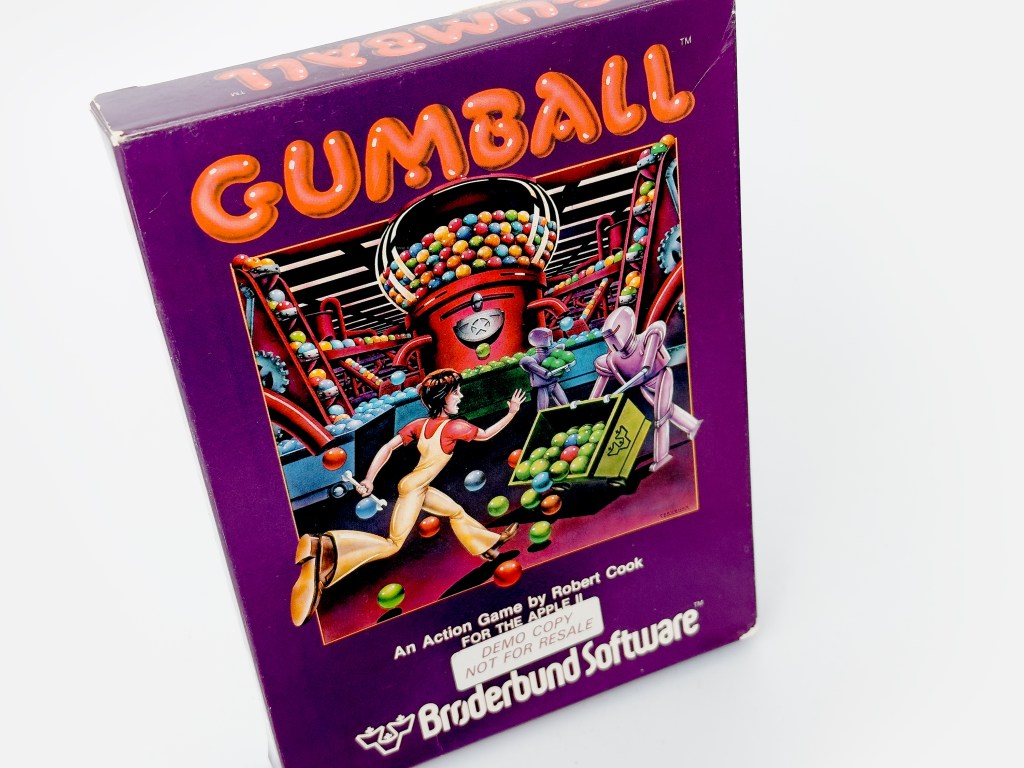

Set in a candy factory, Gumball puts you in the shoes of an industrious factory worker who must manage a maze-like machine to sort gumballs by color. Although the setup may sound simple, the game quickly unfolds into a challenging experience packed with split-second decision-making and strategy, along with a considerable amount of stress building up as you progress.

The idea behind Gumball came from Brøderbund’s co-founder Doug Carlston, who initially envisioned a color-sorting machine. Programmer Robert A. Cook took the concept and transformed it into a whimsical gumball-sorting factory within just a week, designing the basic structure and gameplay that would become the backbone of the game. Cook’s factory featured pipes, valves, and bins, a simple yet effective setup that simulated the clatter of a factory line.

Cook’s technical journey had begun in 1976, at age 11, when he ordered his first computer kit, a $100 Netronics ELF II from Popular Electronics. The Elf was an early microcomputer equipped with the same RCA 1802 microprocessor that flew aboard NASA’s Galileo spacecraft and later was used in the Hubble Space Telescope. The computer and its 256 bytes of memory gave Cook a taste for computing’s creative possibilities and by age 15, he was already designing database software.

In 1983, at 18 years of age, Cook graduated from high school but postponed university to join the personal computer revolution when he was hired by Brøderbund Software to do contracted service and to produce what would become Gumball for the Apple II, a computer he had first encountered at a friend’s house.

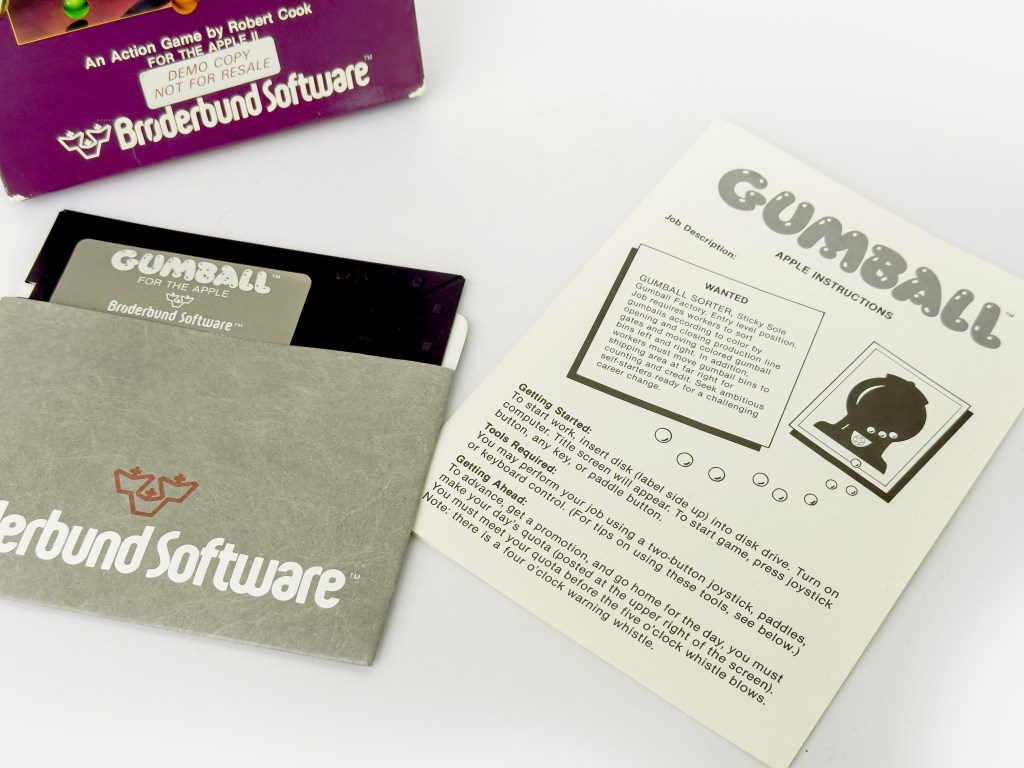

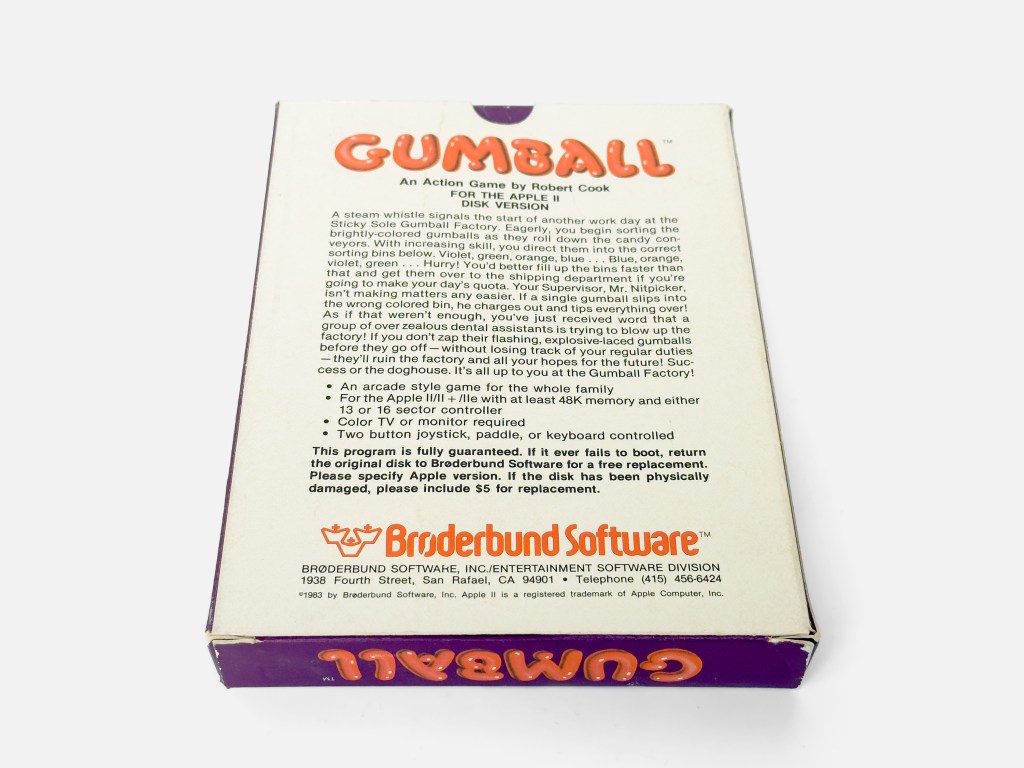

Gumball was released for the Apple II, Commodore 64, and Atari 8-bit line of home computers in 1983, and featured surprisingly detailed graphics and animations for its time. Players control the factory’s valves, directing gumballs into color-coded bins under the watchful eye of the factory foreman. Any slip-ups and that same foreman appears on-screen, humorously dumping out the rejected gumballs in frustration. Progressing through levels adds even more challenge, with additional colors to sort, tighter time limits, and exploding defective gumballs that require careful handling.

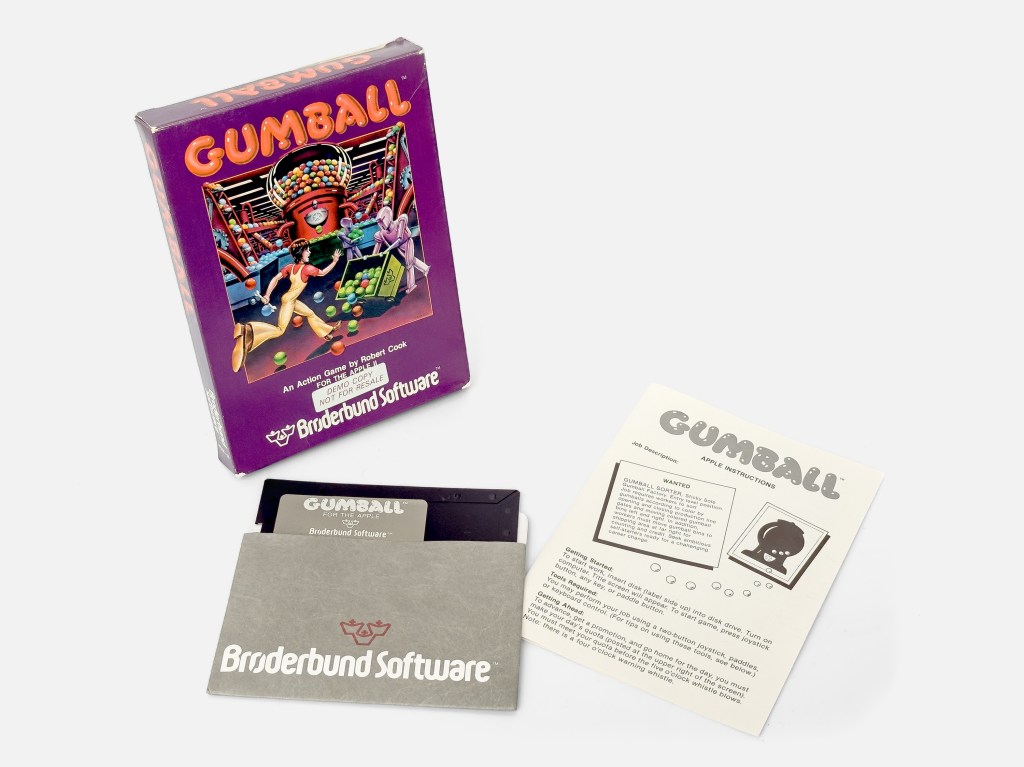

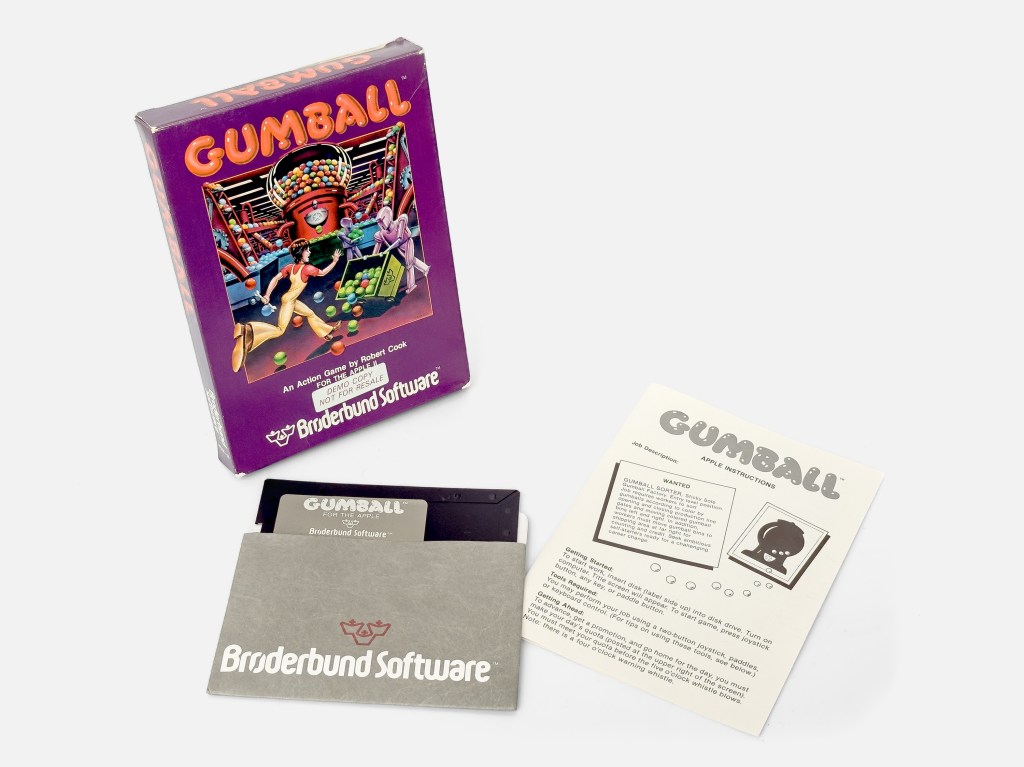

Designed by Robert A. Cook and released for the Apple II by Brøderbund Software in 1983, Gumball brought co-founder Doug Carlston’s concept to life in a uniquely challenging game.

Gumball challenges you to sort gumballs by color under intense pressure. When the steam whistle blows, it’s go-time! Match colors accurately, or the foreman will come and angrily dump your bin, costing precious time. Each level pushes you further: stray gumballs hit the floor, quotas get higher, and from level four, you have to deal with exploding gumballs planted by mischievous dental assistants.

From level three onward, production speed has to be ramped up, sending both the gumballs and your blood pressure soaring!

Early reviewers were impressed, with Computer Gaming World noting the game’s “delightful” animations, describing how the gumballs would amusingly tip out of their bins after sorting mistakes. In Compute!’s Gazette, the humor and “comical” aspects, especially the foreman’s reaction, were applauded. Critics appreciated the game as a clever departure from fast-paced shooters, highlighting how its pace and escalating complexity made it a true test of timing, logic, and hand-eye coordination.

Aside from the gameplay itself, Gumball carried a humorous, almost satirical undertone. Softalk magazine went so far as to speculate that it might be a commentary on “the Great American Dream of climbing the corporate ladder.” With every successful round, players received a mock “promotion,” moving from worker to foreman to manager and beyond, showing that corporate progress in Gumball involved the same endless grind.

While Gumball never received any widespread commercial success and quickly faded into obscurity, an unexpected twist, gained renewed attention over 30 years later when a hacker and digital preservationist known as 4am in 2016, fought his way through the Apple II version’s incredibly advanced copyright protection, only to discover that each game phase hid a cipher of a long-buried Easter egg, a hidden message left by Cook.

By the mid-’80s, when details of Easter eggs were eagerly shared across BBSes in text files, rumors spread that Gumball was packed with hidden messages and secrets. Yet, despite the game’s reputation, no one had publicly uncovered Cook’s ultimate Easter egg, concealed behind an intricate cipher.

The Easter egg, hidden as an end-game message, required players to find a code revealed by pressing CTRL + Z during the cutscenes between levels. Curious about the mystery, 4am enlisted the help of his occasional “partner in crime,” qkumba, to test the technique. They discovered messages appearing after each level, which 4am soon recognized as a substitution cipher. With the help of an online solver, he decoded the messages: “ENTER THREE, LETTER CODE, WHEN, YOU RETIRE.” Pressing CTRL + Z at retirement reveals the final clue: “DOUBLE HELIX.” Enter “DNA,” and Cook’s hidden messages appear:

AHA! YOU MADE IT!

EITHER YOU ARE AN EXCELLENT GAME-PLAYER

OR (GAH!) PROGRAM-BREAKER!

YOU ARE CERTAINLY ONE OF THE PEOPLE

THAT WILL EVER SEE THIS SCREEN.

THIS IS NOT THE END, THOUGH.

IN ANOTHER BR0DERBUND PRODUCT

TYPE 'Z0DWARE' FOR MORE PUZZLES.

HAVE FUN! BYE!!

R.A.C.

When 4am shared the discovery on Twitter, Cook, surprisingly answered “WELL DONE. I assumed it would take a thousand, but you solved it in a mere 33 years.“

The other Brøderbund product referenced by Cook remains unsolved, as far as I know. Although he later ported Jordan Mechner’s Karateka to the Atari 8-bit and Commodore 64, that didn’t happen until 1985, ruling those out. Games in development around the time of Gumball included Matchboxes, Operation Whirlwind, The Arcade Machine, Spelunker, Lode Runner, Drol, The Serpent’s Star, and Spare Change. My best guess would be Drol or Spare Change as likely 1983 candidates. If we look at titles published in 1984, Brøderbund released Dazzle Draw, The Print Shop, Stealth, Captain Goodnight and the Islands of Fear, Whistler’s Brother, Raid on Bungeling Bay, and Karateka, as some of these were in development during 1983, they could also be potential candidates.

The copy protection on Gumball would go down in hacker lore as one of the most brilliant and difficult copy protection systems devised, with attempts to crack it being featured in many prominent magazines and discussion boards in corners of the hacking community. Following its release it was relatively quickly cracked but only partly as it was an incomplete copy of the game. Later attempts would have the game working completely, but would fail to discover the associated easter egg hidden within the game – though it seems that the hints were discovered but overlooked until 4am found and deciphered them.

Though Gumball didn’t see substantial commercial success, its intricate graphics and challenging gameplay earned it a unique place in the Brøderbund catalog. The hidden messages, including a secret credit screen, reflected the spirit of early ´80s gaming culture, where developers would weave personal touches and hidden surprises into games, like a signature on a piece of art. These hidden elements help obscure titles like Gumball stay relevant, sparking renewed interest with every new discovery.

Following, Cook stayed in California to freelance for a number of years before enrolling at Yale University, earning a BS in Computer Science. He designed D/Generation, a puzzle-action classic, and in 1997 he worked as the technical director on The Last Express, the iconic real-time adventure by Jordan Mechner. In July 2005, Cook co-founded Metaweb Technologies, a company devoted to organizing the world’s information into structured databases that later would be acquired by Google. At parent company Applied Minds, Cook led the San Francisco office as Director of Knowledge Product Development.

In 2017, Cook came out as transgender, adopting the name Veda Hlubinka-Cook.

Sources: Wikipedia, VICE, Reddit, lotico. Yale Daily News Historical Archive, Twitter…