During the rapid evolution of the gaming industry in the 1980s, Dynamix emerged as one of the most creative and prolific developers of its time. Founded in 1984 by Jeff Tunnell and Damon Slye in Eugene, Oregon, the studio quickly built a reputation for producing a diverse array of innovative and technically impressive games.

While the company initially focused on simulation and action games, Dynamix president Jeff Tunnell was deeply intrigued by the potential for games to tell stories in a more cinematic way. He admired adventure games for their narrative possibilities but found the text-parser-driven gameplay of the era cumbersome, believing that there had to be better ways to integrate storytelling and interaction.

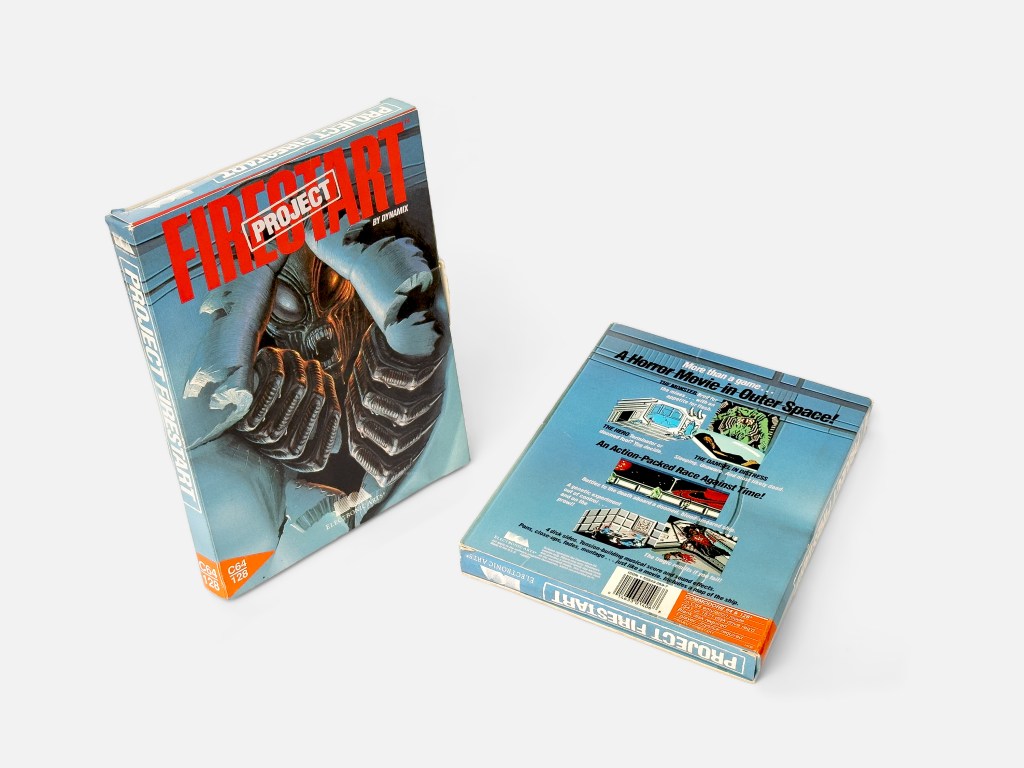

Dynamix’s first step toward creating a more cinematic gaming experience came with Project Firestart, an ambitious title for the Commodore 64 that pushed the limits of the aging system. Released in March 1989 by Electronic Arts, a year behind schedule, the game stood out for its atmospheric tension, cinematic cutscenes, and innovative narrative elements. It was the company’s most demanding and ambitious project to date, with development spanning three years but the technical limitations of the Commodore 64 had constrained ambitions. Regardless, Project Firestart showcased the studio’s potential, hinting at what Dynamix could achieve when more advanced technology became available.

By the time Project Firestart was released, Dynamix’s relationship with Electronic Arts had started to strain. Restrictive publishing contracts limited the company’s creative freedom, ultimately prompting Dynamix to buy itself out. As a result, Project Firestart received little to no marketing support, was never released in Europe, then the largest market for Commodore 64 games, and quickly faded into obscurity despite its impressive qualities.

Project Firestart, designed by Jeff Tunnell and Damon Slye, was published for the Commodore 64 by Electronic Arts in March 1989.

Influenced by the first two Alien movies, it is considered the first survival horror game. With a cinematic approach, adventure game-like elements, and multiple endings, it marked the company’s early steps toward the adventure genre.

With Electronic Arts in the rearview mirror, Dynamix’s current games in development found a new home with Activision and by late 1989, the studio was ready to release its first two titles under the Dynamix banner, A-10 Tank Killer and David Wolf: Secret Agent. These were distributed through Activision’s affiliated publisher program and helped establish Dynamix’s own brand identity.

At the time, the adventure game market was flourishing, and advances in gaming technology were opening up new possibilities for Tunnell’s vision of cinematic and interactive storytelling. In response, his company set up an image production studio, complete with photography and lighting facilities, color scanning and image processing capabilities, and a photo development lab. The studio also brought in Sher Alltucker, who was tasked with overseeing make-up, costume design, and casting actors, key elements in realizing Tunnell’s ambition to blur the line between movies and gaming.

In the late summer of 1988, Tunnell, along with Dave Selle, began crafting the story and initial design for what was to become Dynamix’s first adventure game, Rise of the Dragon. Heavily influenced by Ridley Scott’s iconic 1982 film Blade Runner and the cyberpunk works of William Gibson, the project aimed to transport players into a gritty, futuristic world, but early in the process, Tunnell recognized that the scale of the game quickly proved to be beyond the reach of the company’s current technology and resources. Not only would the game need to be larger and more ambitious than anything Dynamix had previously attempted, but also require the development of an entirely new game engine.

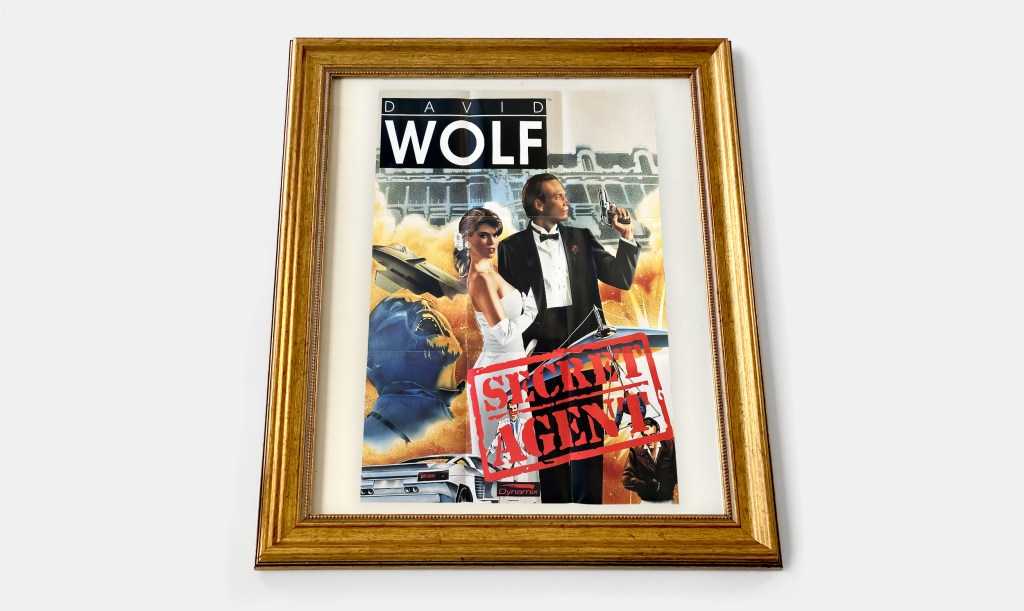

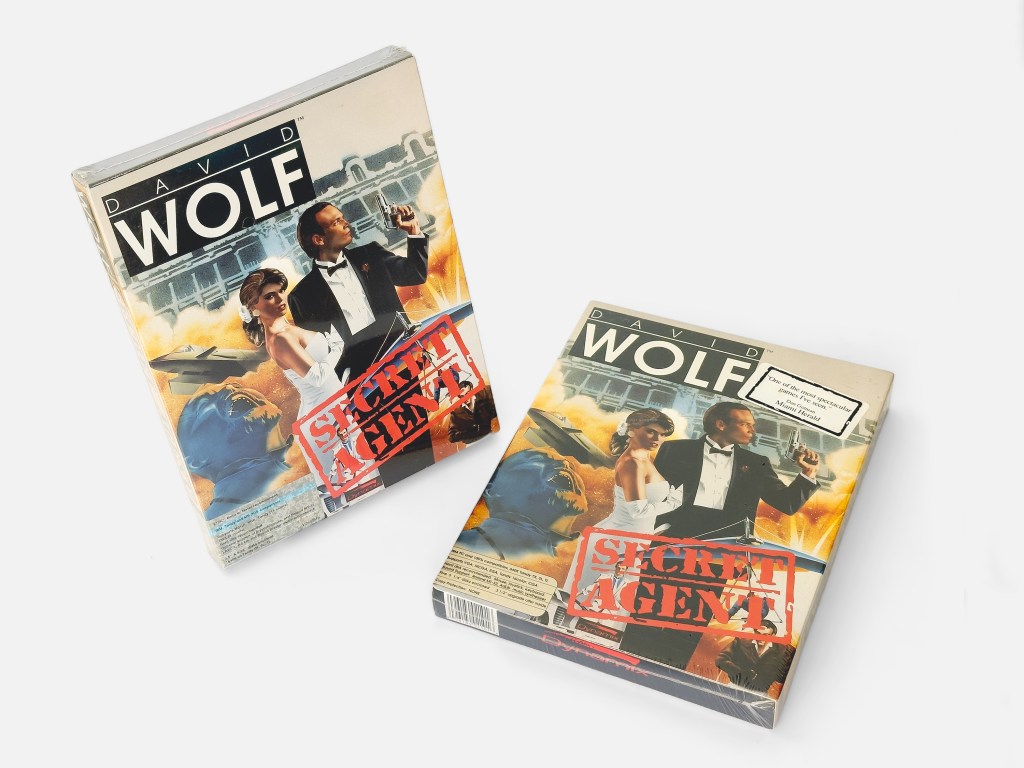

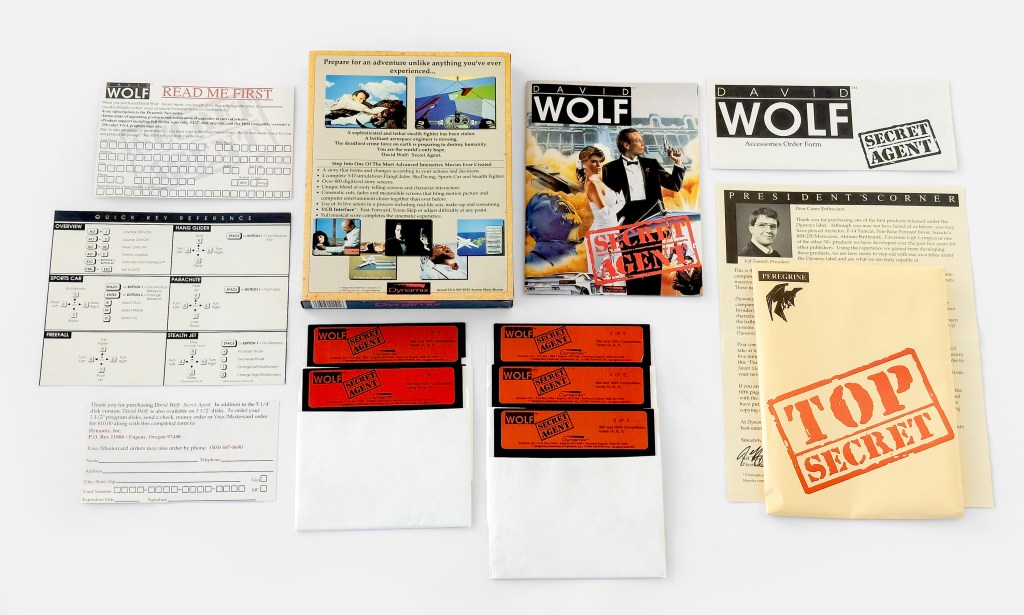

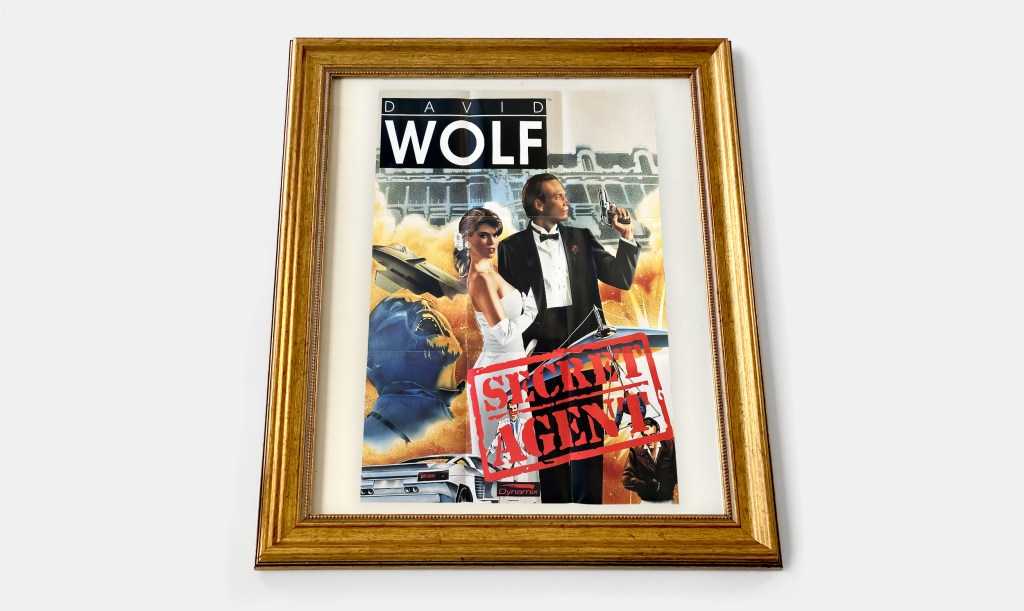

It was decided to temporarily shelve the project, and Dynamix shifted its focus to a more manageable project, David Wolf: Secret Agent. Using the newly established image production studio and its proprietary 3Space 3D game technology, the team created a game that blended action, simulation, and narrative into a cinematic experience. The new studio was used to create digitized images of real actors, costumes, and sets, to craft a game reminiscent of a James Bond movie. The game presented a series of action-packed mini-games, connected by a digitized movie-like storyline, and controlled through a VCR-style interface that allowed players to adjust difficulty and skip to different parts of the game.

David Wolf: Secret Agent was released in December 1989 through Activision’s affiliate publisher program.

The game used Dynamix’s advanced 3Space technology for its 3D action simulation scenes and a digitized cinematic narrative to tie it all together.

Despite its innovative approach, David Wolf: Secret Agent sold poorly and received mixed reviews upon release. While critics admired its ambitious visual style and cinematic presentation, many found the gameplay too limited and the overall experience too short. Regardless, the valuable lessons learned from the project laid a vital foundation for Dynamix’s forthcoming adventure games.

David Wolf: Secret Agent came with its own movie-style poster, designed to capture the game’s cinematic flair and James Bond-like theme.

On August 22, 1988, 600 miles south of Eugene in central California, Ken Williams, president and co-founder ofSierra On-Line, the leading company in the adventure game genre, announced that his company had filed a registration statement for an initial public offering, aiming to raise over $10 million in working capital. 45 days later, in October, the company started trading on NASDAQ under the symbol SIER. Sierra planned to utilize the net proceeds for general purposes, including working capital, product development, potential acquisitions of complementary businesses, and 3rd party developed technologies to leverage the company’s future games.

Dynamix’s exceptional game technology caught the attention of Williams, who, in the autumn of 1989, traveled to Eugene to visit the 25-man operation. Initially, he sought to license the company’s impressive 3Space technology, used in its various 3D games, including David Wolf andRed Baron, an upcoming World War I flight simulator that would become the company’s best-selling title the following year. Dynamix’s technology would enable Sierra to compete in the simulation and action market, which boasted nearly 10% more sales than the adventure game genre Sierra dominated. Williams secured a licensing agreement but quickly recognized the greater potential in acquiring the entire company, given the talent Dynamix had amassed in both design and programming.

Dynamix’s four owners, Tunnell, Slye, Kevin Ryan, and Richard Hicks, acknowledged that the gaming industry was becoming increasingly challenging for a small independent company. Financial constraints often posed significant limitations on their game designs and the projects they pursued. An influx of capital was necessary to fulfill ambitions and to remain competitive in an increasingly demanding industry. On March 27, 1990, an acquisition agreement with Sierra On-Line valued at $1.5 million was reached, with the final legal arrangements completed during the summer. The acquisition granted Dynamix nearly full autonomy, allowing them to set their own creative agenda while continuing operations from their Eugene offices.

The acquisition provided Dynamix with the financial stability and resources needed to realize its ambitious adventure game projects, as permitted by Sierra. Tunnell and Slye revisited the documents and preliminary work for Rise of the Dragon and, with Jerry Luttrell, developed the plot while a new game engine, the Dynamix Game Development System, DGDS, was being developed simultaneously.

The new engine was instrumental in bringing Rise of the Dragon to life, crafting the complex storylines, interactive environments, and rich character interactions required for an advanced point-and-click adventure game. The engine supported state-of-the-art 256-color VGA graphics, a significant upgrade from the 16-color EGA used in David Wolf just months earlier, and also enabled multiple developers to work simultaneously on different aspects of the game, allowing non-programmers, such as artists and writers, to contribute directly to the game’s creation.

Under the art direction of Randy Dersham, Robert Caracol, who had joined Dynamix from Dark Horse Comics in 1988, began developing conceptual art for the characters and settings. Blending elements of graphic novels with cyberpunk aesthetics, the team crafted a dark, mature, and brooding atmosphere that was rarely seen in the adventure game genre at the time. To accommodate the scale of the project, the team opted for painted character portraits rather than digitizing real actors in their image production studio. Hand-painted backgrounds were scanned into the computer and layered with digitized renderings, video clips, and fully computer-generated ambient animations. Text was integrated through a custom interpreter, while programmers hard-coded special cases for specific scenes and implemented the game’s intricate logic.

An original musical score, composed by local Eugene guitarist and composer Don Latarski with help from Christopher Stevens, who also contributed to the sound design, perfectly complemented the dystopian cyberpunk atmosphere.

Rise of the Dragon was Dynamix’s largest and most ambitious project to date. By the time it passed quality testing in 1990, the game had required an astounding 11,000 man-hours to complete. It featured over 80 scenes, 12,500 individual animations, and 26,000 pieces of text—all accomplished in the span of just one year. When the game was released in November 1990, it faced stiff competition from Sierra’s own highly anticipated title, King’s Quest V, which launched the same month. Both games showcased cutting-edge 256-color VGA graphics and featured fully point-and-click interfaces. Together, they helped usher in what would later be regarded as the Golden Age of Adventure Games.

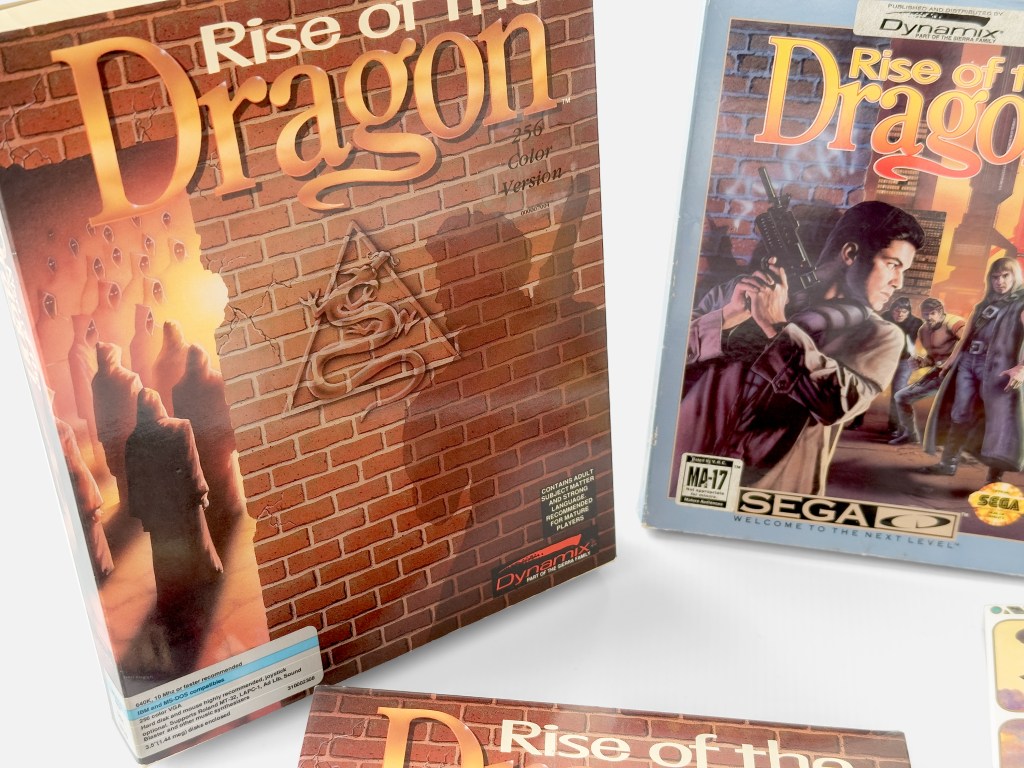

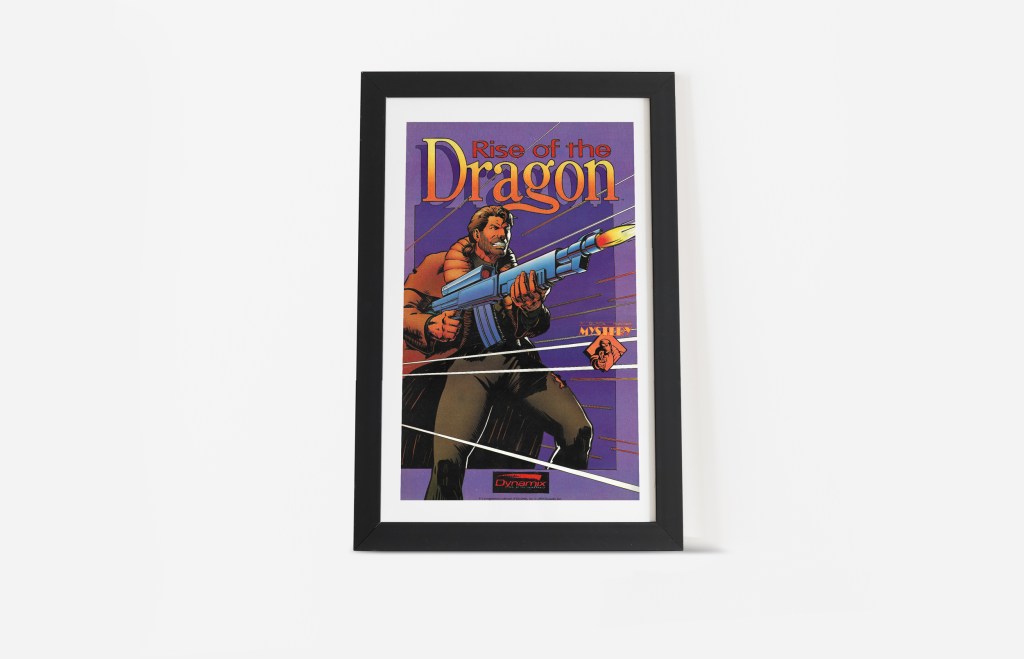

Dynamix’s first adventure title, Rise of the Dragon, was published by Sierra On-Line for IBM PCs in November 1990.

The game was released in two separate versions, a 16-color EGA version and a 256-color VGA version.

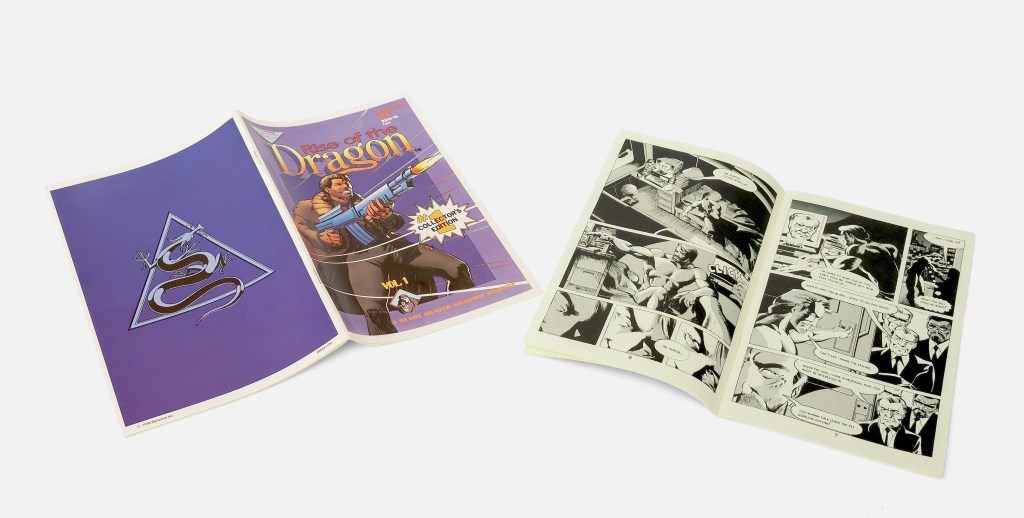

A hint book to assist players was made available in early 1991.

The beautiful 27-page book presents the backstory as a comic along with an overall introduction to the gameplay.

Set in a neon-lit, dystopian, crime-ridden 21st-century Los Angeles, Rise of the Dragon follows former L.A. police detective William “Blade” Hunter, whose unorthodox methods have forced him into early retirement. Now a private investigator, the death of the mayor’s daughter has him, unofficially, assigned to uncover a conspiracy involving a new, sinister, and highly addictive drug causing genetic mutation and death.

Rise of the Dragon combines point-and-click adventure elements with interactive sequences, such as action scenes and mechanical puzzles. The player’s choices influence the plot, with characters remembering earlier behavior and responses. A real-time clock advances the storyline ,causing events to unfold on a schedule, affecting character behavior and the availability of locations. Multiple endings, based on the player’s choices, a relatively novel feature at the time, offered some replay value.

Rise of the Dragon centerfold poster from Sierra News Magazine Vol. 4 No. 1 – Spring 1991

Rise of the Dragon was well-received upon its release in 1990, earning praise for its mature themes, storytelling, impressive VGA graphics, and comic book-style cutscenes. Versions for the Commodore Amiga and a Macintosh were released the following year.

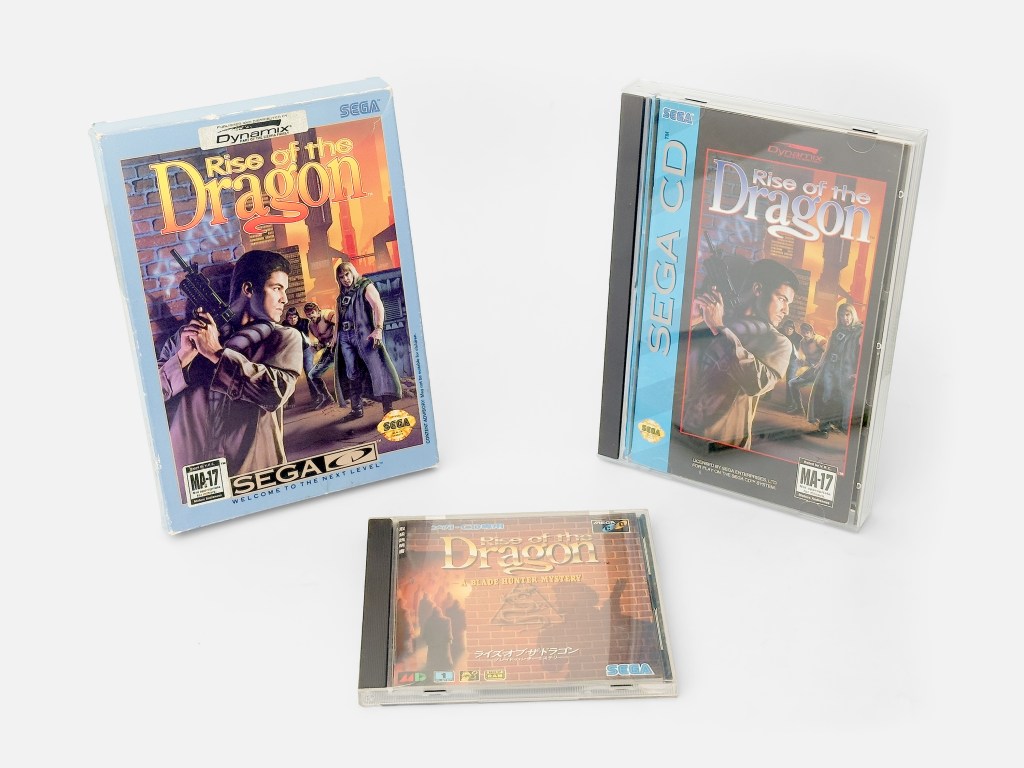

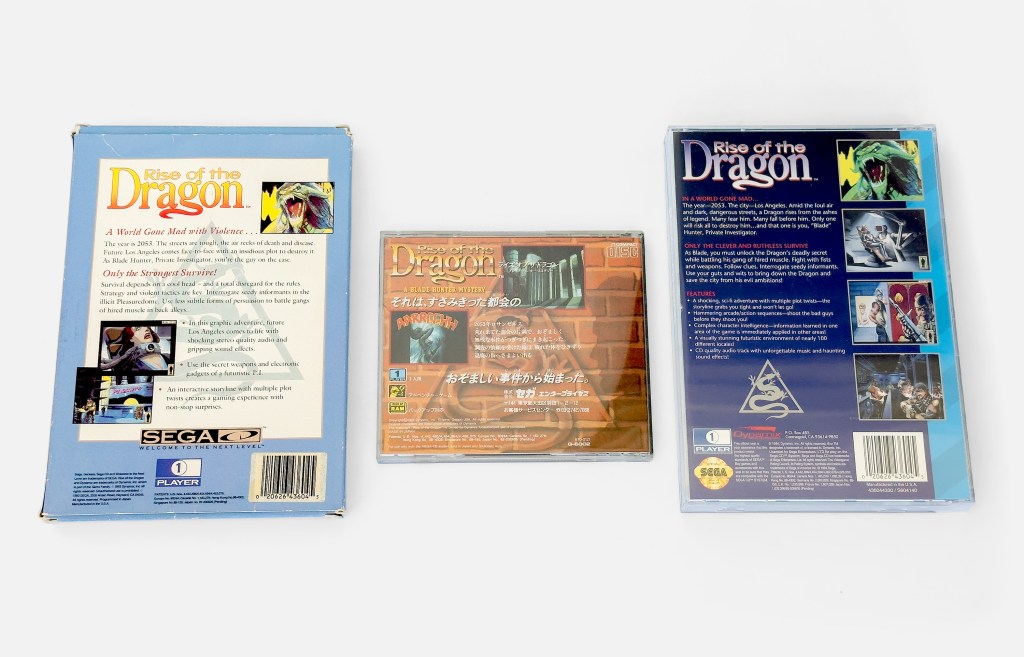

At the time, the computer industry was making significant advancements in storage technology, with compact discs offering nearly 500 times the capacity of a standard 3.5″ floppy disk. Looking for ways to leverage the game and expand sales beyond the home computer market, a new version was announced in the fall of 1991. The version was targeted at the newly introduced Sega CD console, which had debuted in the Japanese market. The port was produced by Japanese Game Arts, with whom Sierra had built an intercontinental partnership with, converting and distributing its products for the U.S. and European markets.

In September 1992, Rise of the Dragon made its debut on the Sega CD in Japan, and Dynamix soon began working on a North American version, which would be released the following year. The U.S. version featured full voice acting by professional actors, including Cam Clarke, known for his roles as Leonardo and Rocksteady in the 1987 Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles animated series. Despite undergoing several content changes due to its mature themes, the Sega CD version still received an MA-17 rating from the Videogame Rating Council.

The transition to the Sega CD brought some graphical challenges. The original 256-color VGA graphics had to be down-converted to fit the Sega CD’s 64-color palette, which resulted in darker visuals with a noticeable green tint. Despite the limitations, the version retained the core elements of the game that had made the original a success.

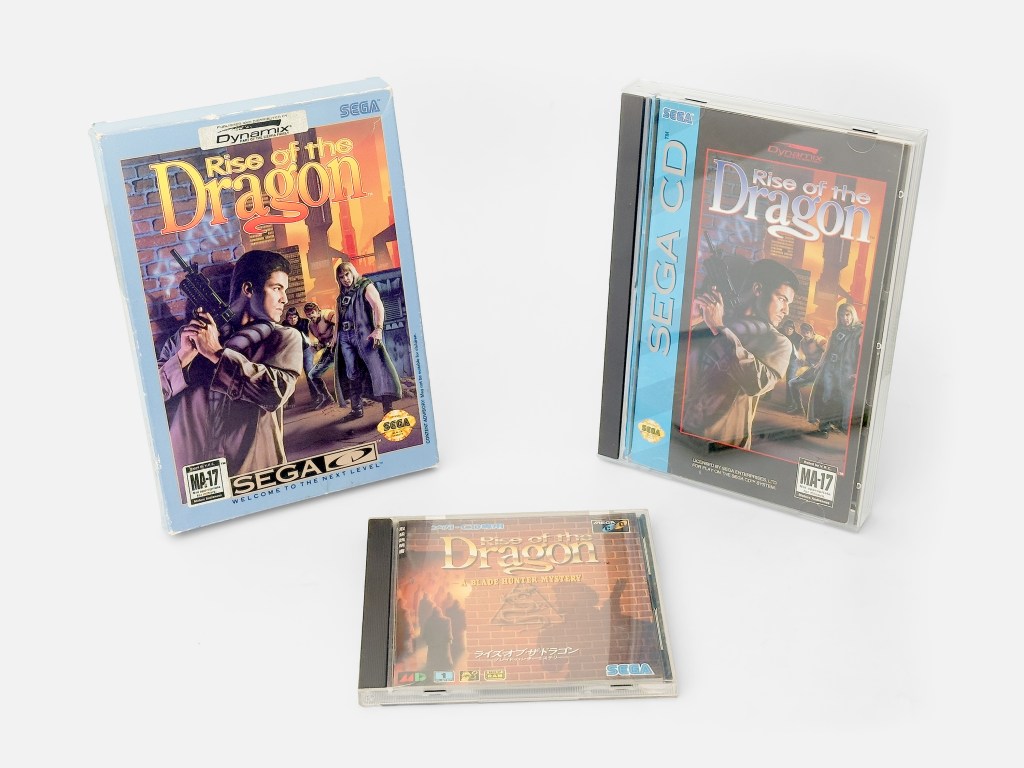

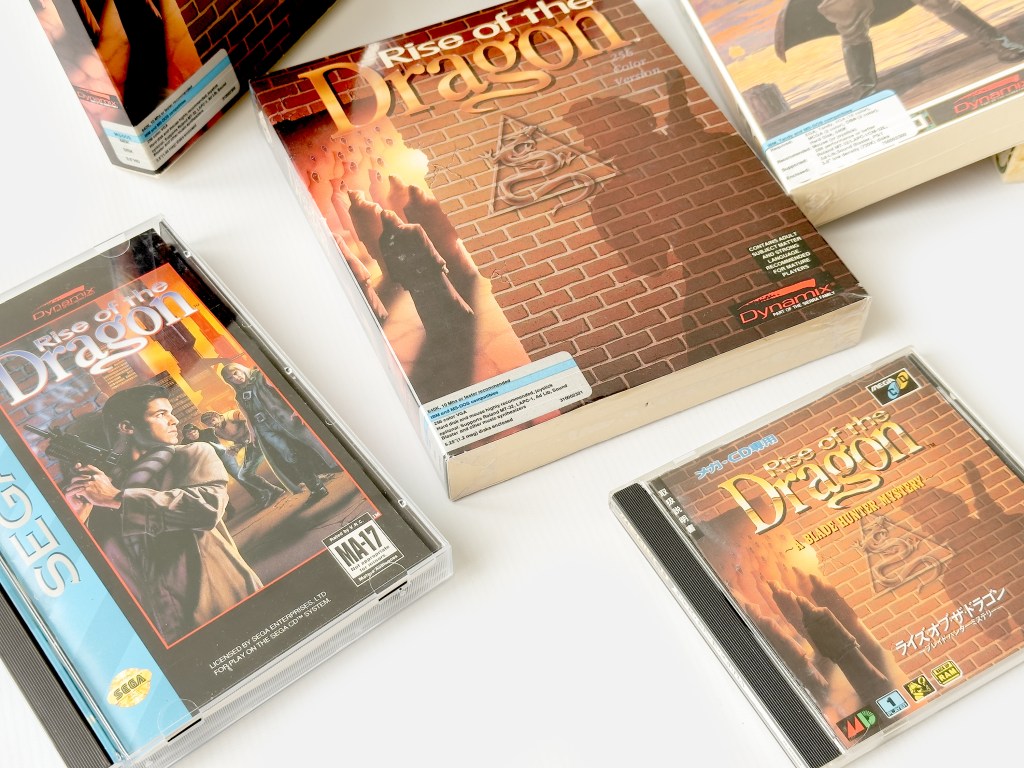

Japanese Game Arts, for whom Sierra On-Line had published Thexder and Silpheed in North America in 1987 and 1989, ported Rise of the Dragon to the Sega CD. The Japanese version, released in September 1992 (center), featured full Japanese voice acting. The North American Sega CD version followed in 1993, initially packaged in a cardboard box (left) as part of the first batch of Sega CD games. It was later re-released in the standard Sega CD jewel case (right).

In conjunction with Rise of the Dragon’s development, Tunnell shifted focus to completing the design and directing Dynamix’s next adventure title, Heart of China, which preliminary design had been conceived in the summer of 1989. The dystopian cyberpunk setting was replaced with a vibrant, classical adventure experience, featuring a mix of romance, action, and intrigue, drawing heavy inspiration from movies like Raiders of the Lost Ark, Romancing the Stone, and High Road to China.

To push the cinematic feel further, the team decided to use the image production studio to digitally capture live actors for the game’s numerous characters. The shooting process demanded a substantial amount of effort and extended for well over a year, running parallel to the work of the designers and programmers. Over eighty actors were cast, many, due to a restricted budget, from Dynamix’s own staff, including Slye. Actress Kimberly Greenwood, portraying Kate Lomax, discovered she was pregnant a few months into shooting. At that point, recasting and re-filming were considered prohibitively expensive, prompting various techniques to conceal her growing bump.

The actors were decked out in period-correct costumes, many rented from major film studios and photographed in front of white backdrops before being rotoscoped and superimposed on top of the scanned-in hand-painted backgrounds. The combination of painted artwork and digitized actors was unlike most attempts at the time, seamless and extremely well-executed. Multiple protagonists, each with their unique skills and personalities, were incorporated into different parts of the game, allowing players to switch between the hot-headed and arrogant Lucky, the calm and collected ninja, Zhao Chi, and Lomax. The 3Space technology was utilized in a single 3D action scene where players have to escape warlord Li Deng‘s fortress in a World War I-era tank.

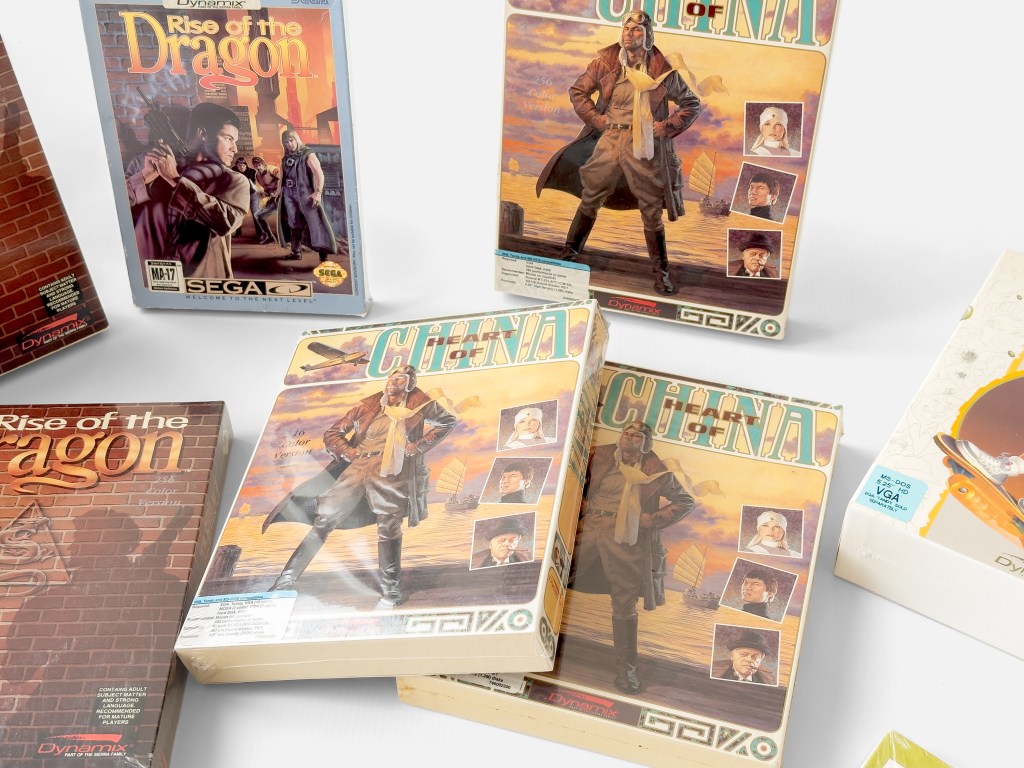

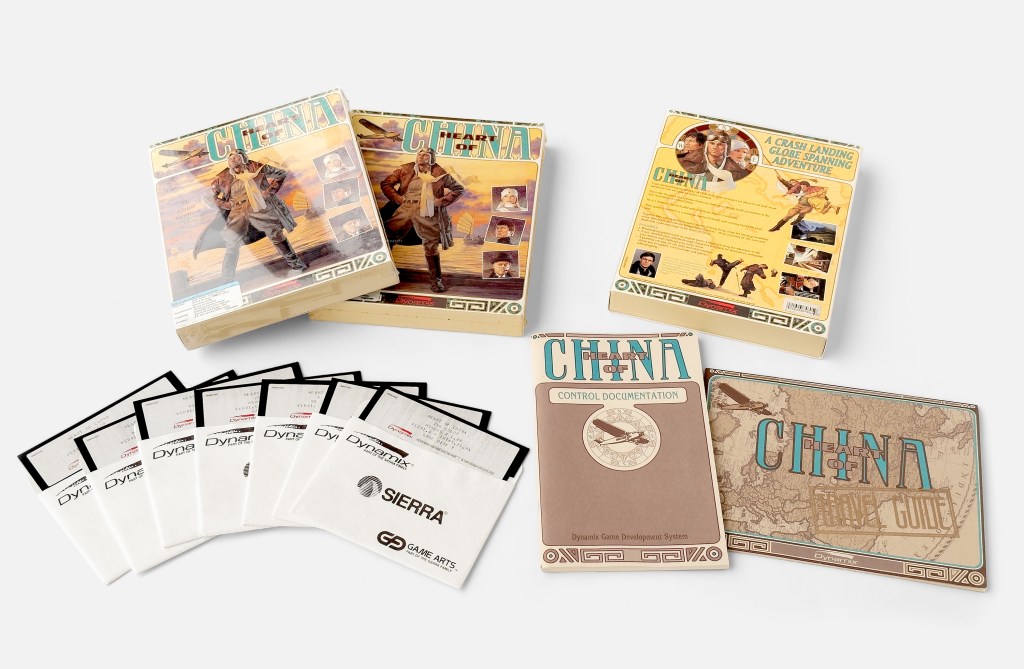

Heart of China, Dynamix’s second adventure game, was released for IBM PCs and the Commodore Amiga in 1991, with a Macintosh version following in 1992.

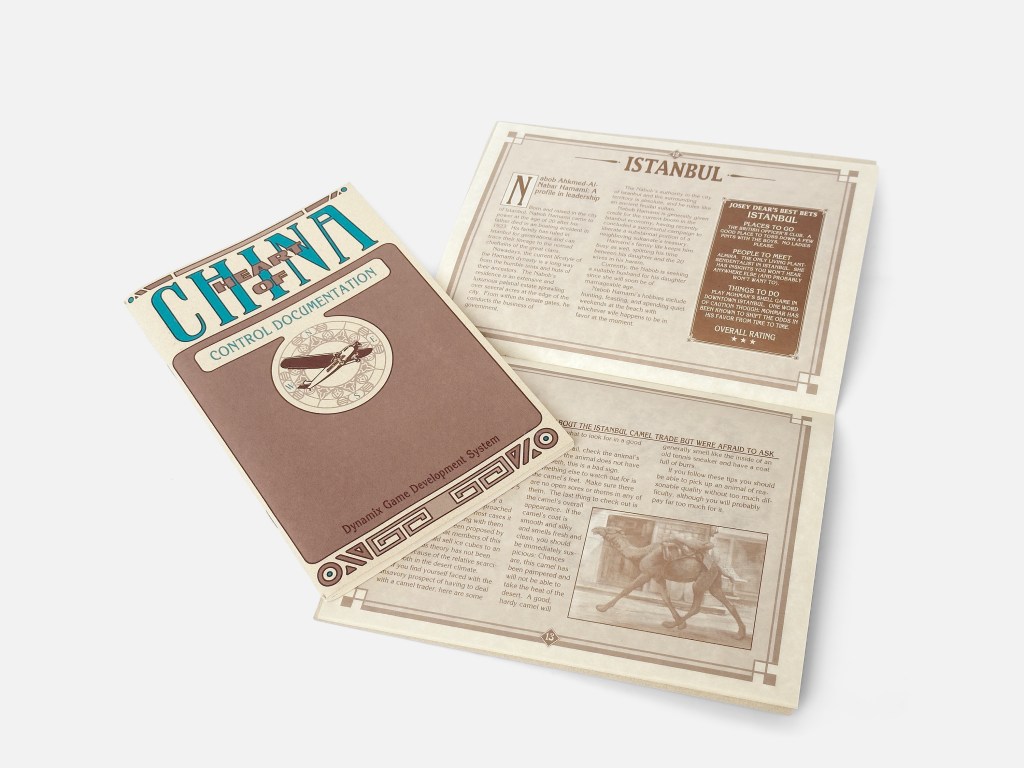

The documentation was designed to resemble authentic travel journals from the game’s 1930s setting.

Set against the backdrop of 1930s Asia, Heart of China follows the adventures of Jake “Lucky” Masters, a former World War I pilot turned mercenary. Lucky is hired by the wealthy American land tycoon Eugene Adolphus Lomax III to rescue his kidnapped daughter, Kate Lomax who has been kidnapped and held hostage near Chengdu, in the mountains of China, by feared warlord Li Deng. Travel to Hong Kong, locate the mysterious Chinese ninja Zhao Chi, and find a way to infiltrate Li Deng’s fortress and rescue Kate.

Heart of China was much more light-hearted than Rise of the Dragon but offered much of the same gameplay. The player was presented with choices, where different approaches led to a changing story with different outcomes.

Upon its release, Heart of China received generally positive reviews. Critics praised its captivating storyline, vibrant classic adventure atmosphere, and innovative use of technology that seamlessly blended painted artwork with digitized actors, setting it apart from most other adventure titles on the market. The portrayal of the 1930s period setting was also widely commended, as were the game’s mechanics and its unique system of multiple protagonists. While several magazines named it the best and most visually stunning game of 1991, a few reviewers noted minor shortcomings in gameplay and pacing.

During 1990, Tunnel joined forces with artist Brian Hahn and animator Sheri Wheeler, a veteran of Disney and Filmation Studios, to explore his vision of combining the charm of traditional animation with the interactivity of games. Together, they started experimenting with various concepts centered around the adventures of a nine-year-old boy and his world. Although the team had gained considerable expertise from the other adventure game projects, creating an interactive cartoon would require blending traditional animation techniques with cutting-edge computer technology and demanded specialized processes and craftsmanship.

Former NBC and Family Home Entertainment writers Tony and Merle Perutz were brought on to write the screenplay and collaborated with Tunnell, Dave Selle, and Tom Brooke to develop the puzzles, dialogue, and characterizations. Shawn Sharp, who had joined Dynamix in May 1990, was appointed Art Director and tasked with overseeing the game’s visual direction. Wheeler enlisted the help of artists Pat Clark and Rene Garcia, as well as several animators with backgrounds in traditional art and classical animation.

Clark, who had previously worked on the popular He-Man and the Masters of the Universe animated series, was appointed Animation Director. Meanwhile, Garcia, a veteran of The Little Mermaid, Scooby-Doo, and the original Flintstones series, took on the task of hand-drawing the backgrounds, which were copied onto illustration boards, painted, and then scanned into the computer. Seven full-time animators were responsible for creating the animation cels by hand, working on light tables in black and white. Each frame of animation was digitally captured and colored using Electronic Arts’ Deluxe Paint Animation software. Once the backgrounds and animation cels were completed, they were assembled into the various scenes of the game. The labor-intensive process took several months, with Tunnell personally overseeing each step of production. In total, a team of around 40 people worked tirelessly for a year to complete the project.

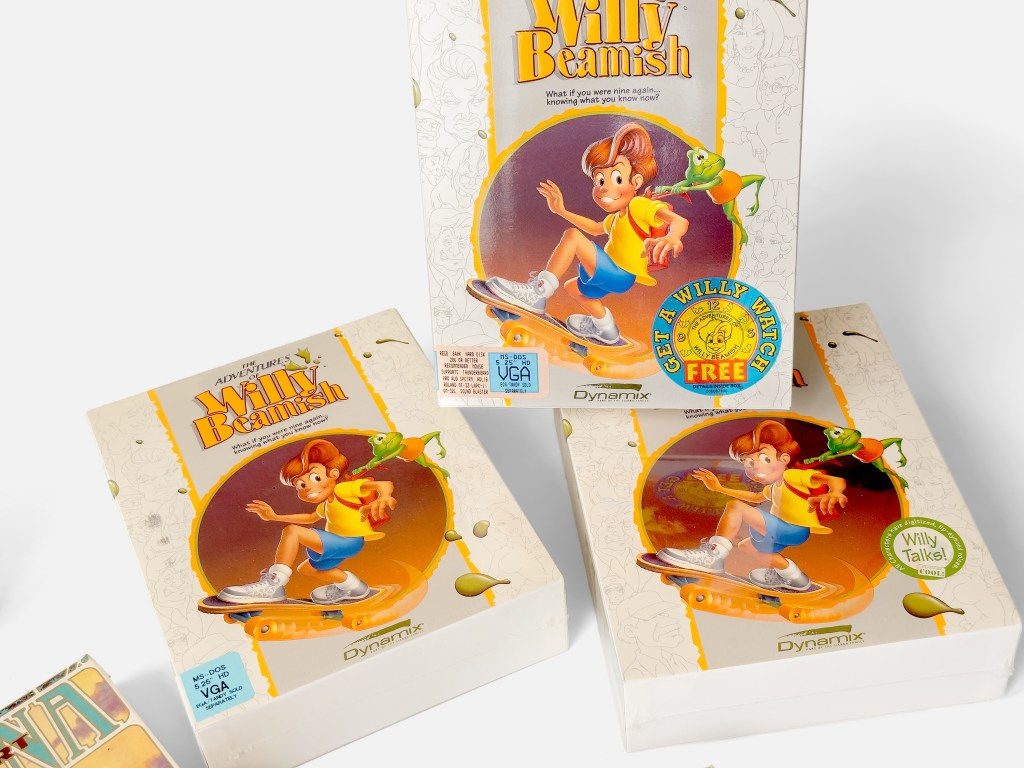

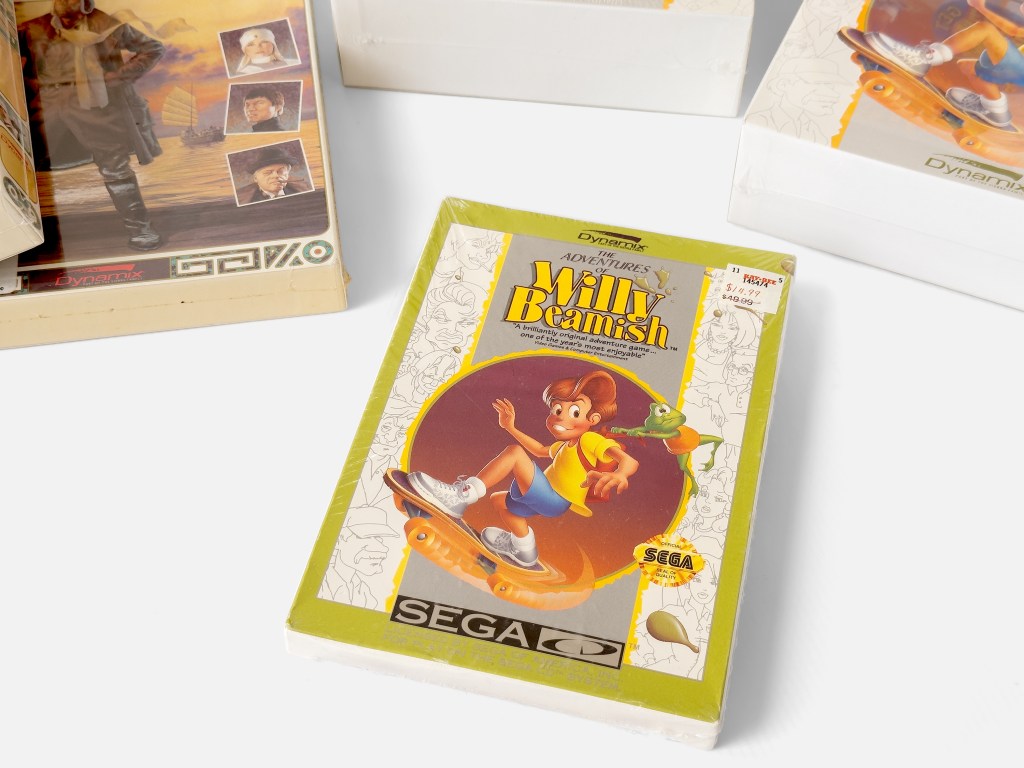

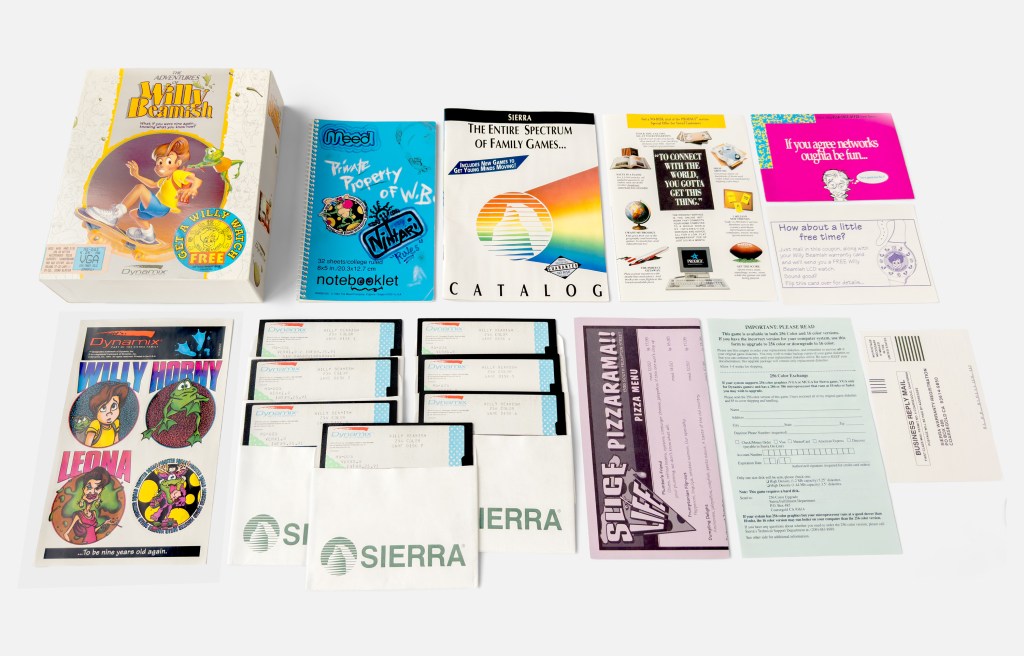

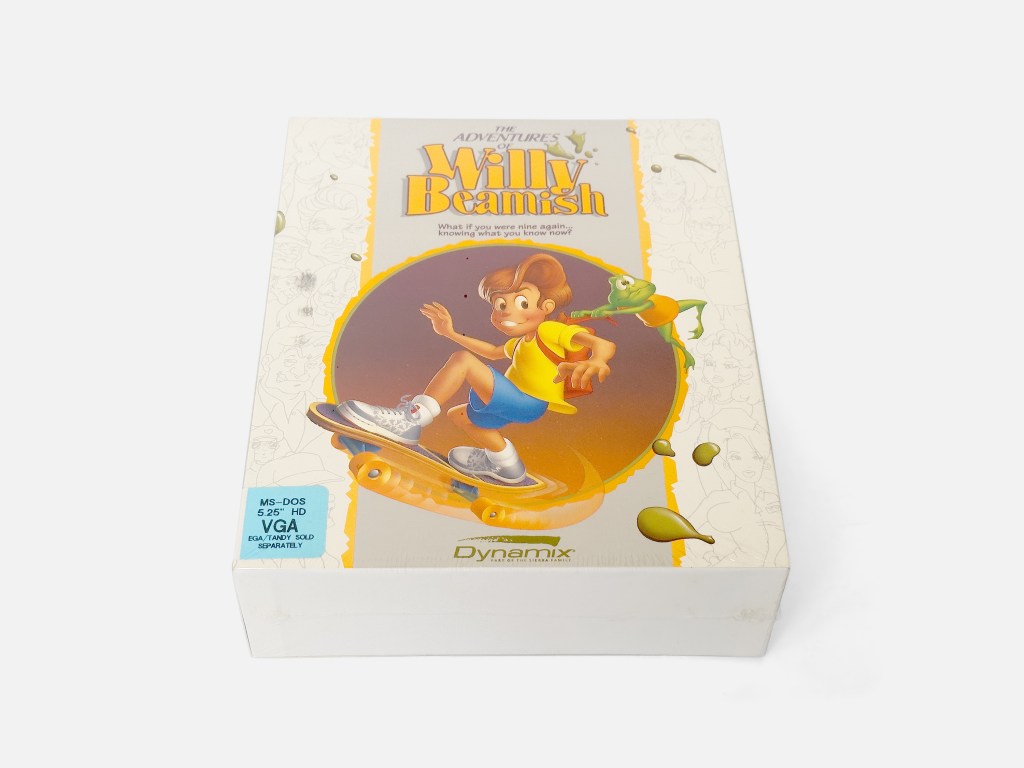

Dynamix’s third and final adventure game, The Adventures of Willy Beamish, was released for IBM PC in the summer of 1991.

The original release included an offer slip for a free Willy LCD wristwatch.

Versions for the Commodore Amiga and Macintosh followed in 1992.

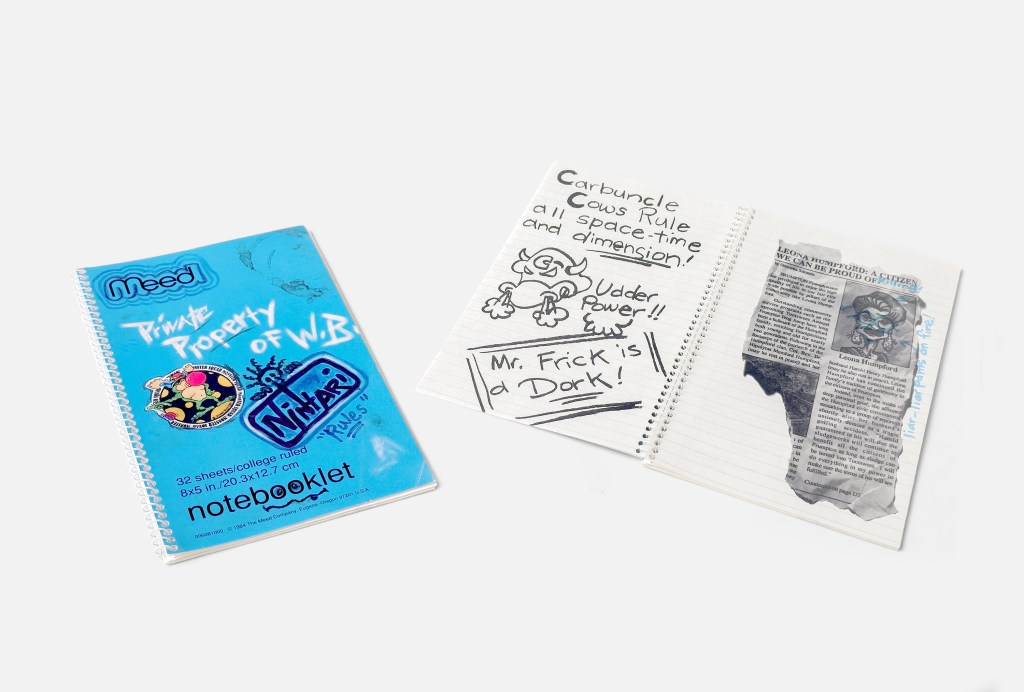

The manual, a spiral-bound booklet designed to look like a 9-year-old’s notebook, featured whimsical illustrations, doodles, cut-out articles, and even a speech written by Willy himself about his dream of becoming the ultimate Nintari champion.

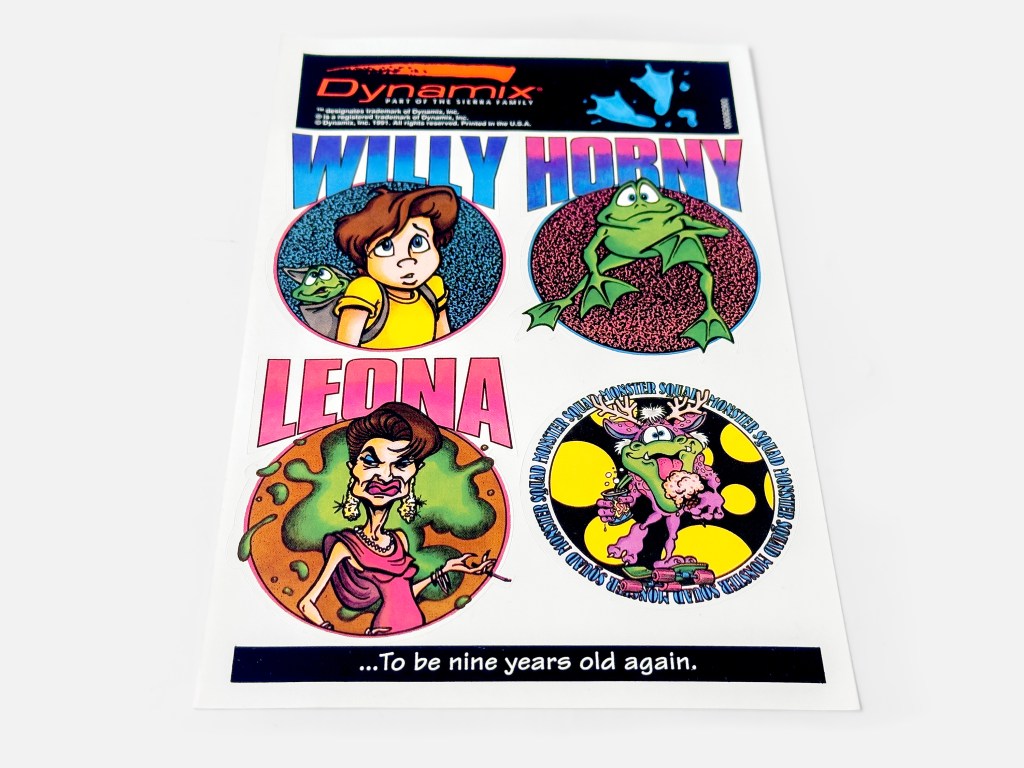

The game included four stickers featuring Willy, Horny, Leona, and the Monster Squad.

The Adventures of Willy Beamish follows a typical nine-year-old with an overactive imagination and a knack for getting into trouble. Set in a suburban town, the game begins on the last day of school before summer vacation. Willy dreams of winning the Nintari Championship, a video game competition, but is faced with a series of obstacles. From school bullies to dealing with his yuppie mom and avoiding his neurotic father’s punishments to outsmarting his bratty little sister, all while trying to save the town from a nefarious plot hatched by the town’s corrupt mayor and the sinister owner of a toxic waste company.

A version of The Adventures of Willy Beamish, without the “Get a Willy Watch” sticker on the cover.

Upon its release in 1991, The Adventures of Willy Beamish achieved both critical and commercial success, selling approximately 80,000 copies in its first six months. The game was widely praised for its vibrant, detailed animated cartoon graphics and an engaging storyline that appealed to both younger and older players alike.

Given the game’s popularity, work quickly commenced on a CD-ROM version, focusing primarily on enhancing the audio experience. Each of the game’s forty-two characters was voiced by professional actors, but syncing the voiceovers to match the characters’ lip movements proved to be a massive task, requiring much of the original game code to be rewritten to accommodate the addition. Composer Christopher Stevens‘ original score was remastered, with additional tracks recorded to take full advantage of the enhanced audio capabilities.

The 1992 CD version was met with mixed reviews. While the enhanced audio and additional features were intended to elevate the overall experience, the voice acting received substantial criticism. Computer Gaming World harshly remarked that the voice performances were “insulting to children and inconsiderate of adults, whose skin it will make crawl.” Reviewer Charles Ardai went further, expressing a strong dislike for the game’s tone, describing it as having a “smirking, adolescent sexiness as incongruent with a small child as the hero.”

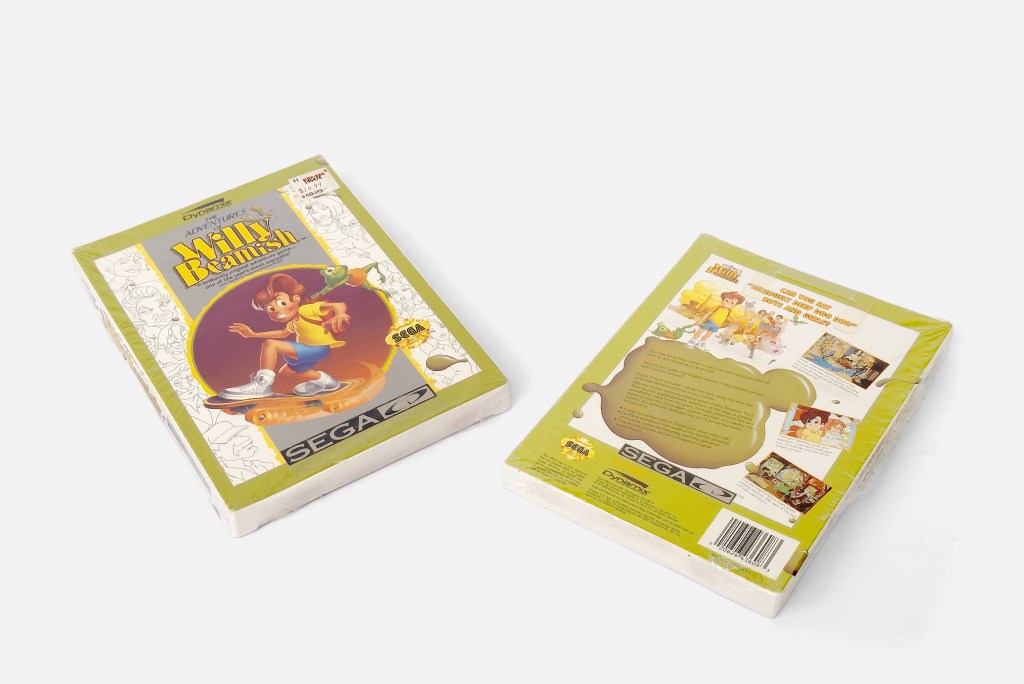

An enhanced version featuring full voice acting, a new intro, and animated character portraits was released in 1992.

The Adventures of Willy Beamish was ported to the Sega CD in 1993 with slightly washed-out visuals because of the system’s limited color palette. A number of smaller changes were made, and the intro (used from the floppy release) was tweaked.

In June 1991, prior to its release, The Adventures of Willy Beamish was showcased at the Summer Consumer Electronics Show in Chicago. The game generated significant hype with many predicting it would become a major success. Encouraged, Dynamix commenced development on a sequel, tentatively titled The Further Adventures of Willy Beamish. The sequel was set to continue Willy’s story, now as a teenager, with Jeff Tunnell once again serving as the main designer and Sharp providing concept art. However, Tunnell’s departure from the project and from the main offices of Dynamix led to its quiet cancellation in 1992.

The influx of capital from Sierra transformed Dynamix’s projects from being often underfunded and scaled back to having the necessary funds to fulfill ambitions. In just two short years, the company had developed three unique, complex, and visually striking adventure titles, a testament to what the company and its talented people were able to achieve under the right circumstances. Although the games shared similar core gameplay mechanics, they were distinguished by their vastly different styles and settings, with each respectfully pushing the boundaries of technological innovation while offering a fresh, diverse perspective on the genre.

Despite selling well, the return on investment, compared to lesser-complex games, fell somewhat short given the considerable time and resources involved. With all three titles released and other popular games like Red Baron and the upcoming Aces of the Pacific making waves, Sierra encouraged Dynamix to refocus on simulation games, a market segment that Sierra itself did not address.

By the time Willy Beamish was released in 1991, Dynamix had expanded to over 100 employees. Feeling burned out from the large-scale productions, Tunnell yearned for the days of working with smaller teams. Consequently, he established Jeff Tunnell Productions, a smaller development studio located a few blocks away from Dynamix’s main offices.

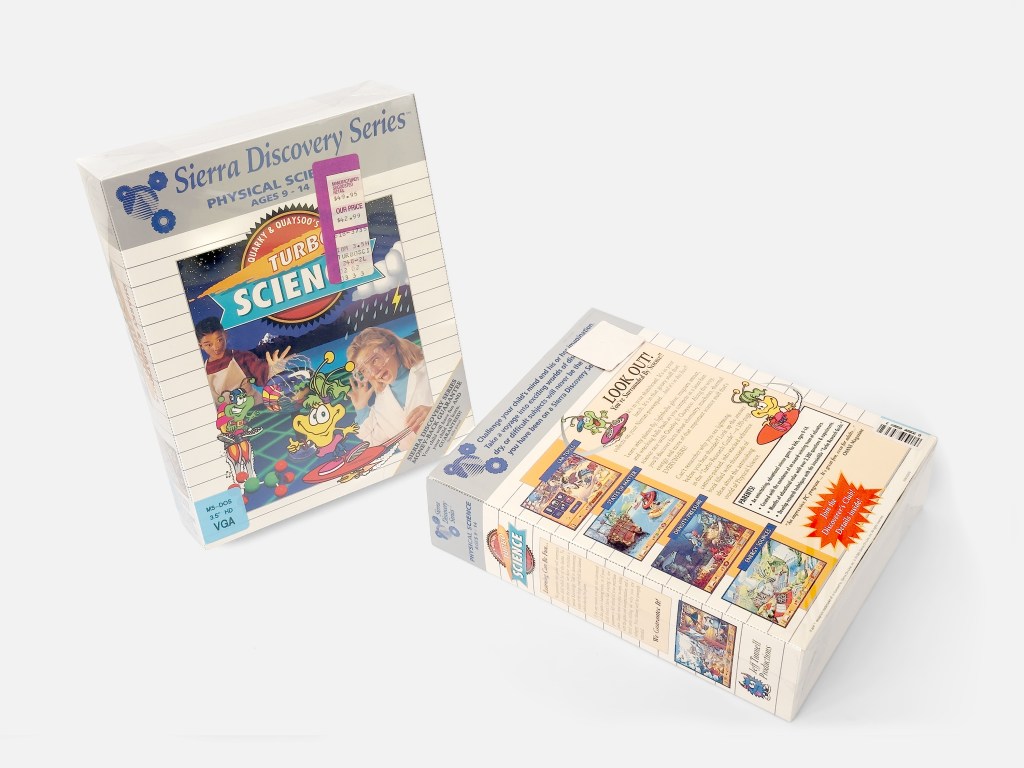

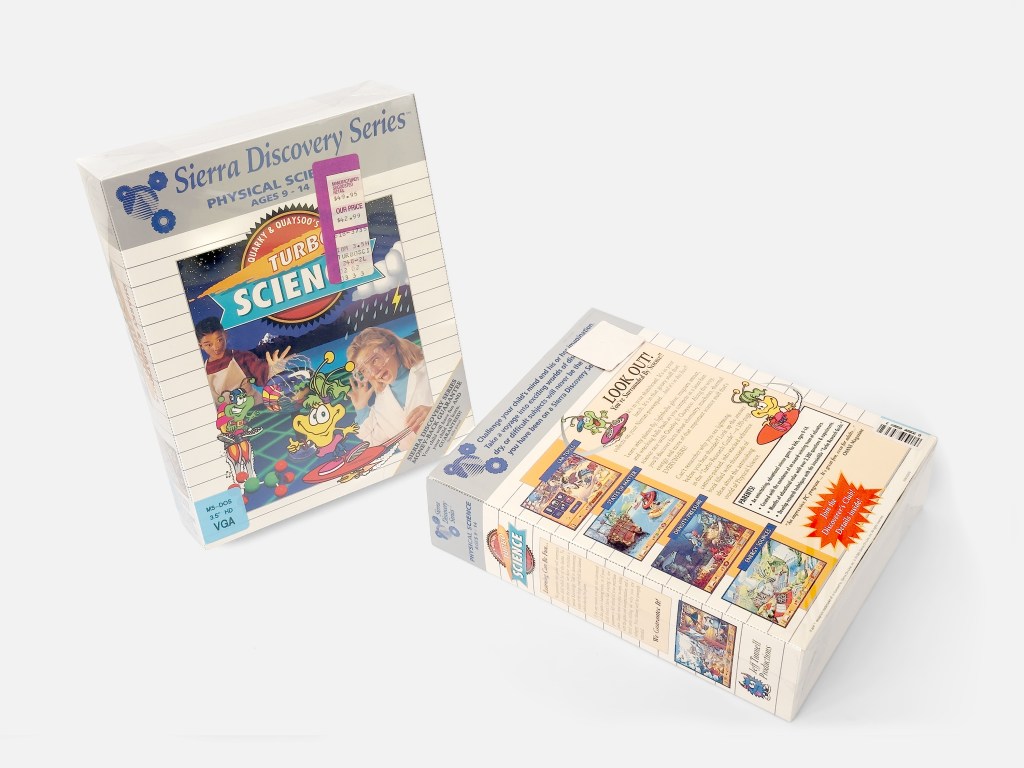

Focusing on casual puzzles and educational games, Tunnell and his team developed Quarky & Quaysoo’s Turbo Science, an educational title designed to teach scientific concepts to children. Featuring graphics in the same style as Willy Beamish, Turbo Science marked the final game to utilize the Dynamix Game Development System.

Jeff Tunnell Productions’ Quarky & Quaysoo’s Turbo Science was published by Sierra On-Line in 1992 in the company’s Discovery Series.

The title became the last game developed in the Dynamix Game Development System.

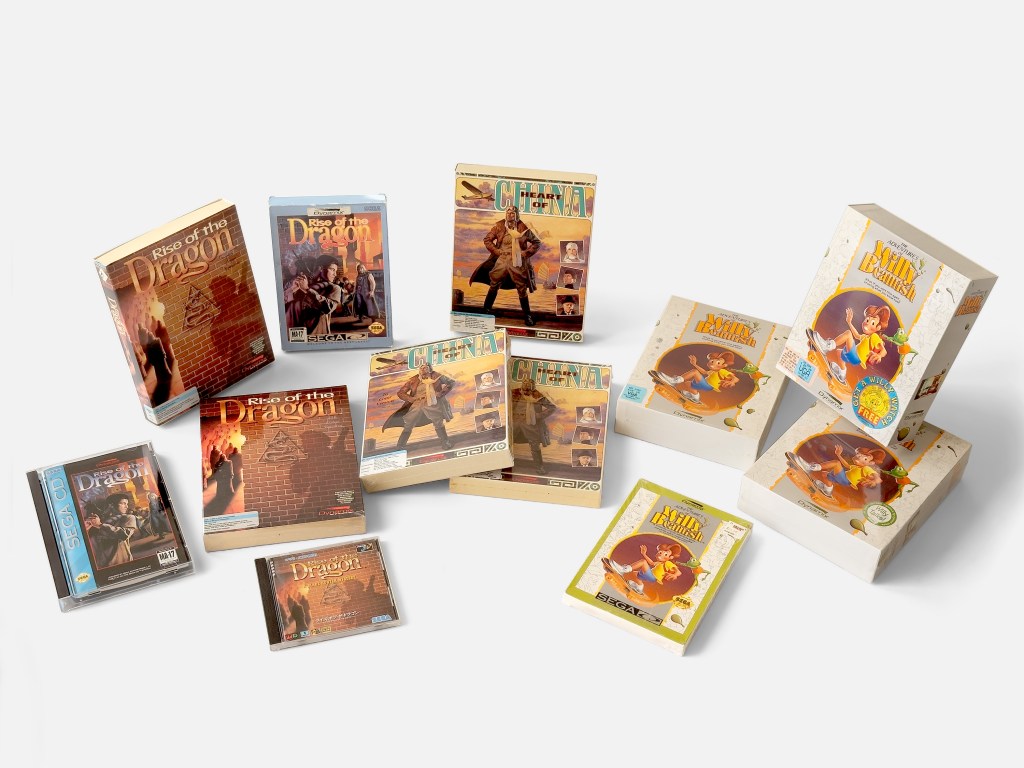

Some of the many puzzle-based contraption games conceived by Dynamix.

Tunnell had aimed to create adventure games with evolving narratives that players could interact with and influence, the result, overall, was nothing short of amazing, but the games highlighted the challenges of balancing narrative depth with interactivity, often resulting in conflicting priorities.

Sources: PC Mag 30. Apr 1991, The Corporate Dictionary, Not All Fairy Tales Have Happy Endings by Ken Williams, Adventure Classic Gaming interview with Kevin Ryan, Rise of the Dragon Hint Book, Sierra News Magazine: Summer 1990, Matt Barton interview with Jeff Tunnell, CU Amiga January 1992, Heart of China Hint Book, The Adventures of Willy Beamish Hint Book, Sega Visions Magazine: February/March 1993, The Art of Point-and-Click Adventure Games by Bitmap Books, InterAction Magazine: Summer 1991/Winter 1992…

I did not enjoy HEART OF CHINA. Hope to get around Willy Beamish.

Great article as always!