Growing up as the oldest of six, Alan Miller spent much time in his youth creating entertaining activities and games for his younger siblings. His father, a surveyor for the federal government, necessitated frequent relocations, often leaving the kids to find their own sources of entertainment. Miller’s creative mindset along with his interest in technology would come to define a prominent career in the industry, spanning over four decades.

Having graduated from the University of California, Berkley with a degree in electrical engineering and computer science in 1974, Miller spent the following years designing aerospace control systems in Silicon Valley. While the work was interesting and challenging it wasn’t as colorful as creating entertainment and creative products. In early 1977 he stumbled upon an advertisement in a local newspaper placed by Atari, looking for engineers to develop game cartridges for its upcoming video game console, the Video Computer System (VCS). Miller, recognizing the potential of microprocessors to transform entertainment along with his own desire to combine technology with creativity, responded to the ad.

In 1976, Atari co-founder Nolan Bushnell had sold his company to Warner Communications, for $26 million, to secure the capital necessary to bring the VCS to market. With the influx of capital, the development of the first games could commence. In February 1977, Miller was hired by Bob Brown of Atari as one of the first four VCS game designers in the company’s newly established Home Programmable Group, tasked with designing games for the VCS.

At the Atari offices, a series of dumb terminals were installed, connected to a central timesharing minicomputer. Miller and his co-programmers would punch in code on the terminals before it was processed and converted by the central computer to assembly code and transferred to Atari console development systems for testing and implementation. Over the next year, undertaking all aspects of the design processes including coding, artwork, and sound, Miller created the games Surround, Hangman, Concentration, and Basketball.

Basketball, one of the first VCS titles to introduce a single-player mode with an AI-controlled opponent marked Miller’s last game project while employed at Atari. As the personal computer revolution took off, Atari wanted to secure its place in the market and began developing the Atari 400/800 line of 8-bit personal computers. During late 1978 and into 1979, Miller, Larry Kaplan, and David Crane spearheaded the development of the required operating system.

In early 1979, as Atari exerted tighter management control, the marketing department circulated a memo to its programming staff. The memo outlined all the games Atari had sold the previous year and provided insights into the percentage of sales contributed by each game to the company’s overall profits. While the memo aimed to showcase which game genres were performing well, to motivate the design team to create more titles within similar categories, some of Atari’s designers, including Miller found themselves less than excited. A game was not merely a commodity, it represented an extension of the designer’s creative essence. Despite their innovative contributions, the designers went unrecognized and underpaid, all while Atari made millions.

By the end of 1979, Atari had moved nearly 2 million consoles and had $100 million in cartridge sales. Miller and colleagues Crane, Kaplan, and Bob Whitehead felt inadequately compensated for their work despite being collectively responsible for 60 percent of the company’s profits from cartridge sales. The “Gang of Four“, disgruntled by the management’s decline to provide more recognition and fairer compensation than the $2,000 each were paid a month, decided to leave Atari, just before the company’s new computers started shipping.

In October of 1979, with music industry executive, Jim Levy, the Gang of Four formed Activision, the first console game developer to operate independently of the console companies. Miller entered as Vice President of Product Development and designed several of the company’s first games for the Atari VCS. While Atari tried every trick in the book to bury Activision in legal battles, the company rapidly grew and by its third year had $159 million in revenue, producing some of the most successful and iconic games for the Atari console, all while becoming the world’s third largest game publisher.

While Atari faltered during the North American video game crash of 1983, Activision, as one of the few, survived but subsequently posted a $18 million loss the following year. After a large devaluation of their stock, Miller and Whitehead thought that diversification to other platforms, such as the extremely popular Commodore 64, was essential for sustained success. Still, the broader company was somewhat resistant to the idea.

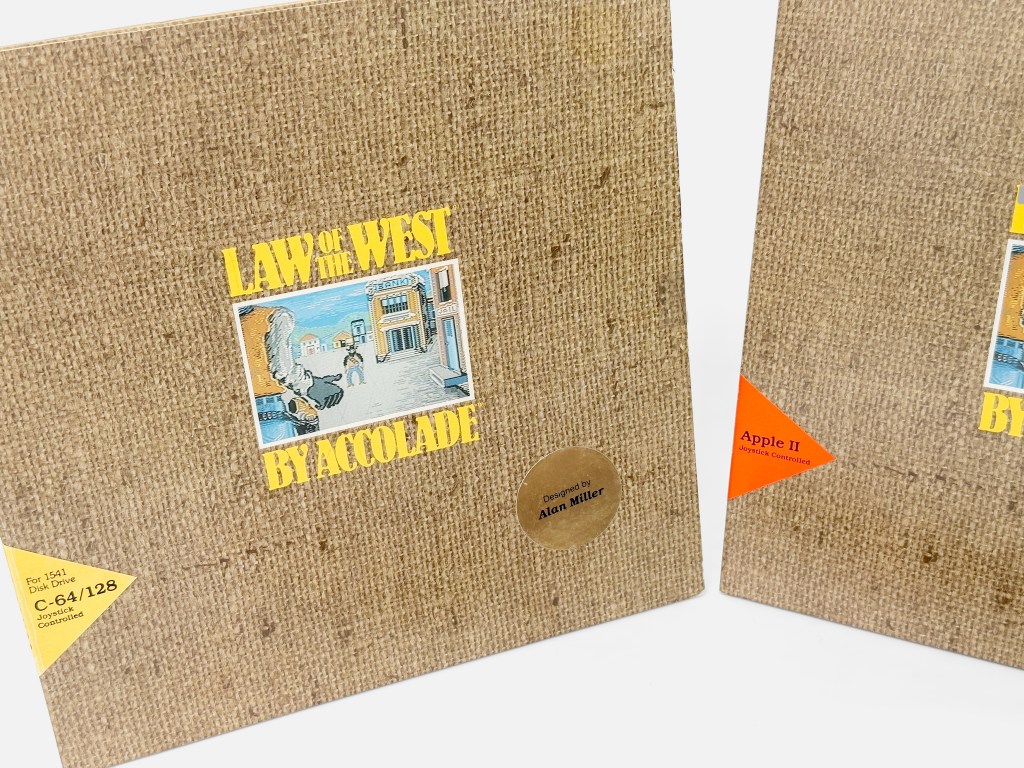

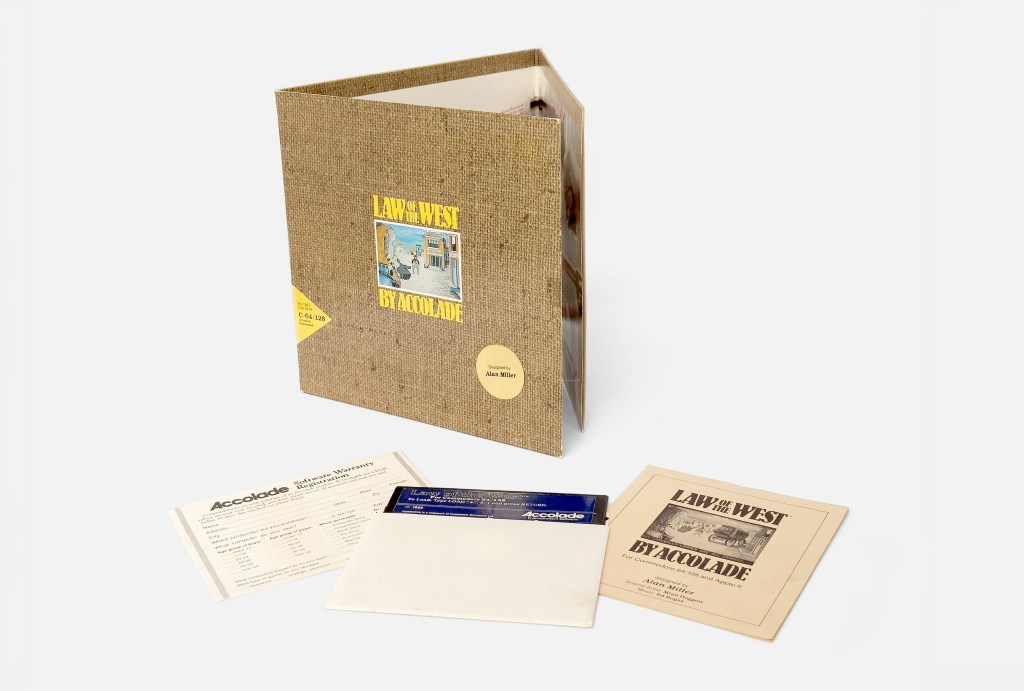

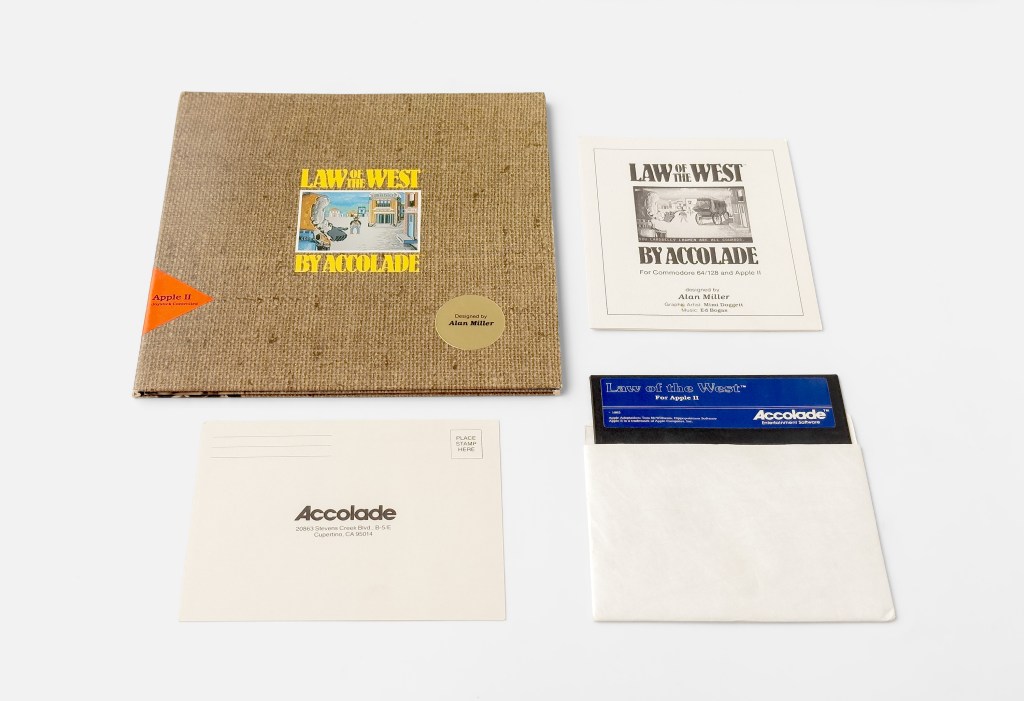

Miller and Whitehead left Activision in 1984 and together formed Accolade. Focusing on home computers such as the Commodore 64, allowed the company to take advantage of the low-cost production required for floppy-based games, compared to the vastly more expensive cartridges that also required licensing fees to be paid to the console companies.

As the video game crash deterred most investors, Accolade was unable to attract investment and Miller and Whitehead had to fund the new venture from their own pockets. The duo hired chief executive officer Tom Frisina to handle managerial duties and from Atari, veteran artist Mimi Doggett. Guided by a vision to think beyond the traditional gaming medium and draw inspiration from other forms of popular entertainment, including television and film, Miller and Whitehead began the development of the company’s two launch titles.

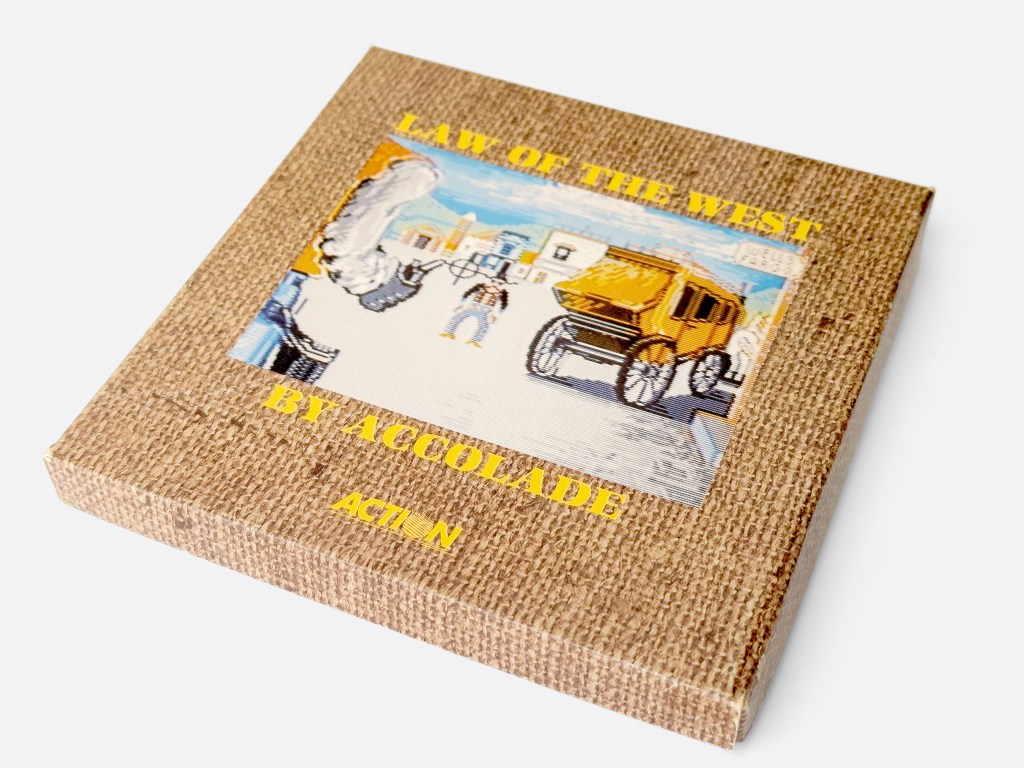

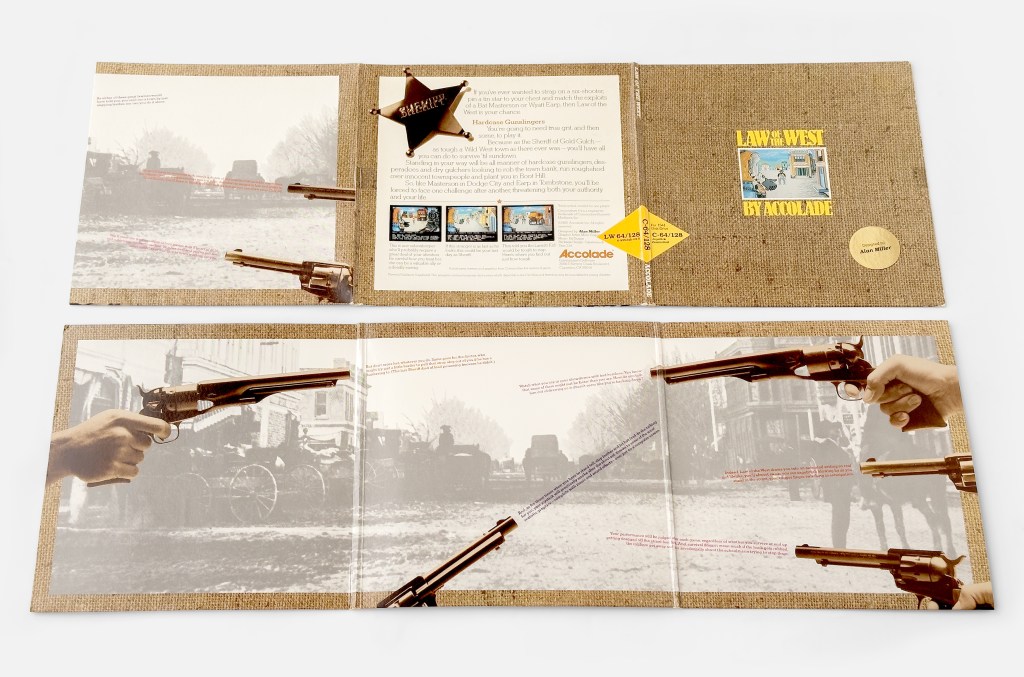

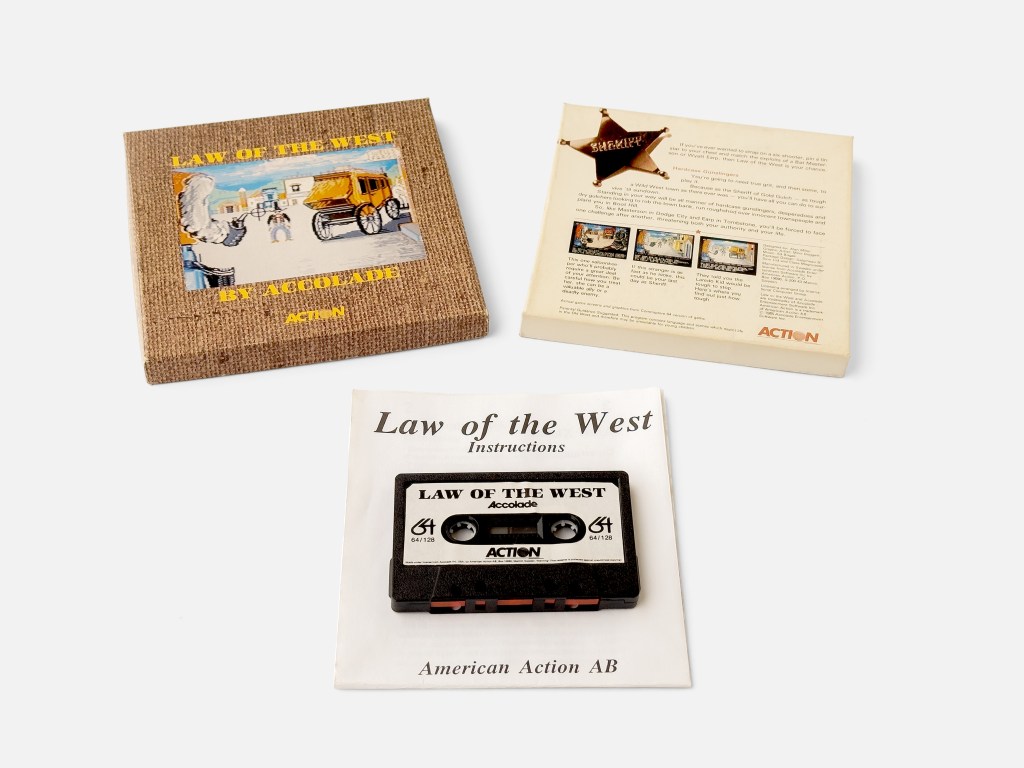

Whitehead, having several Atari VCS sports games under his belt, went to work on Hardball, a baseball game that would present itself as a television-like experience. Miller pursued a unique concept blending gunfights with adventure game elements. Inspired by classic Western movies like the 1952 film, High Noon, he came up with Law of the West.

True to the vision of creating more immersive and cinematic experiences, Miller tasked Doggett with creating the visually captivating and atmospheric Western town setting of Gold Gulch, comprising four different locations. Musician and composer Ed Bogas contributed to the immersive experience with a tailored musical score, leveraging the Commodore’s three-channel SID chip to compose music suited to the various characters and locations within the game. Departing from the conventional text parser interface typical of adventure games, Miller introduced a more user-friendly menu-driven system, offering the player a selection of dialogue options to navigate through the game’s narrative.

The player’s Interactions with characters encountered, spanning from amiable townsfolk to notorious desperados, and the decisions made therein, gunslinging or not wielded significant influence over subsequent character interactions. The unique game design gave some interesting replay value.

The overall score was measured from one to 12 in seven categories by the choices made, whether you lived to see the sunset or not.

The seven categories were how well you maintained your authority, the number of crooks you captured, how well you did romantically, the number of bad guys you shot, how many times you were injured and survived, the number of innocent people you killed, and the number of crimes committed.

When published for the Commodore 64 and 128 in 1985, Law of the West received mixed reviews from critics. While many found the game initially impressive, with striking graphics and a strong atmosphere, it was thought to be too short and limited to have lasting appeal.

Alan Miller’s Law of the West, an Accolade launch title and his first and only title while at Accolade, was released for the Commodore 64 and 128 in 1985.

Law of the West puts the player in the role of a sheriff navigating through a town fraught with danger and moral dilemmas. Departing from traditional text-based interfaces, it featured an intuitive menu-driven system for dialogue choices.

The presentation was cinematic and the gameplay unique, true to Miller and Whitehead’s vision for their company’s games.

Tom McWilliams ported Law of the West to Apple II in 1986.

In most of Europe, Law of the West was published by U.S. Gold. In Scandinavia by Swedish American Action AB.

With commitments elsewhere, Law of the West marked Miller’s sole contribution to Accolade’s roster. In 1994, Miller left the company to pursue a new genre of software and in 1997, co-founded Click Health, a pioneering publisher specializing in health education games targeted at kids with chronic conditions such as asthma, diabetes, and cystic fibrosis. Serving as chairman and CEO, Miller led the company until September 2001 when Click Health ceased operations when unable to gather significant interest from healthcare providers, insurers, and government agencies for the distribution of the games.

The same month as Click Health closed its doors, Miller rejoined Crane at his and Garry Kitchen‘s company, Skyworks Technologies where he served as Vice President of Business Development for a number of years. Today Miller is still active in the technology industry.

Following Miller’s departure from Accolade, the company hired Peter Harris, former head of renowned American toy brand and retail chain FAO Schwarz, to facilitate efforts in securing vital investment. In April 1999, aiming to become the world’s leading interactive entertainment publisher, French Infogrames, acquired Accolade as part of its strategy to gain a solid distribution network in North America. The $60 million acquisition, encompassed Accolade’s workforce of 145 employees, as well as its portfolio of franchises including Test Drive and Hardball, along with licensing agreements with brands such as Major League Baseball. Following the acquisition, Accolade was rebranded as Infogrames North America.

Sources: The Guardian, Wikipedia, Game Informer, InfoWorld, Atari Compendium, The Wall Street Journal…