For the better part of two decades, adventure games held a prominent position in the realm of software entertainment. By the mid-to-late ’80s graphics were replacing text and new visually stunning worlds were heralded into the mainstream and into the hearts of gamers everywhere by the likes of Sierra On-Line and Lucasfilm Games. Companies renowned for their inspiring stories, engaging gameplay, and technological prowess, setting high standards for aspiring competitors eager to enter the thriving market.

Sierra On-Line, in particular, maintained a consistent release of new titles and new installments in its now many successful franchises, firmly establishing its dominance in the market. Consequently, many new contenders experienced only little to moderate success, with otherwise excellent adventure games often going unnoticed amidst the shadow cast by the established players in the industry.

By the early ’90s, MicroProse, celebrated for its large catalog of exceptional simulation and intricate strategy games, was looking for ways to diversify and broaden its business interests. In 1990 and 1991 the company had released Railroad Tycoon and Civilization, both by co-founder Sid Meier. The titles evolved into two of the best-selling strategy games of all time and the success left room for MicroProse to allocate substantial resources towards new ventures.

In 1990 Matt Gruson was hired to set up and assemble the internal Animated Graphic Adventure Group and together with Brian Reynolds develop M.A.D.S., the Microprose Adventure Development System, a framework that allowed for the creation of high-quality dialog and puzzle-driven third-person animated adventure games. The Adventure Group and the framework would be put to good use over the next couple of years, resulting in three visually and gameplay-wise similar but very different themed adventure games.

Gruson would lead the production of all three adventure titles and designed the first, Rex Nebular and the Cosmic Gender Bender, a game inspired by the likes of Sierra On-Line’s popular Leisure Suit Larry and Space Quest series of adventure games. In order to establish a presence in the market and compete effectively with the established players, it was essential to cater to the broadest audience possible, encompassing both experienced players and newcomers to the genre. Consequently, the development team introduced different gameplay modes, including an easy and a hard mode. To enhance accessibility and overall entertainment, the team also introduced a narrative plotting log, authored by Infocom alumni Steve Meretzky. The log served to document the unfolding story as players progressed through the game.

Rex Nebular and the Cosmic Gender Bender, the first adventure title by MicroProse was released in the spring of 1992. The game came on nine 3.5″ floppy disks, a testament to how much space was needed for a contemporary adventure game.

The inspiration from other established adventure games is obvious and while Rex Nebular and the Cosmic Gender Bender has an original quirky storyline, its presentation, graphics, and interface weren’t groundbreaking for 1992.

As Res Nebular you have to retrieve the mysterious artifact dubbed the Cosmic Gender Bender, a device that has the power to alter the gender of any living being. The device has become the obsession of various individuals and factions across the galaxy.

The game has several different possible endings, good, bad, and some in-between, and also features a Naughty mode for adults only and a Nice mode, that could be enjoyed by the whole family.

Following its release in 1992, Rex Nebular and the Cosmic Gender Bender received mixed reviews from critics. Some praised the game for its humor, quirky premise, and creative puzzles, considering it an enjoyable and light-hearted adventure. Its unique storyline garnered some appreciation for its originality but challenging and sometimes illogical puzzles faced criticism and the title didn’t receive the hoped-for acclaim and fell short of being considered a standout debut in the fierce adventure game genre.

By the time Rex Nebular and the Cosmic Gender Bender was released, Gruson and the Adventure Group already had its next title in the pipeline, a mystery thriller based on Gaston Leroux‘s famous 1910 novel The Phantom of the Opera.

Writer Raymond Benson, who as the lead writer for Origin Systems had just completed Ultima VII: The Black Gate, joined the team to write the new adventure. Benson brought valuable experience to the project, as computerized fiction was not unfamiliar to him. Back in 1985-86, he had designed three text-only adventure games for Angelsoft, including an adaptation of Stephen King’s novella, The Mist.

In 1985 and 1986 Raymond Benson designed three of Angelsoft’s text-only adventures, all published by Mindscape.

The two James Bond titles were written by Benson as well.

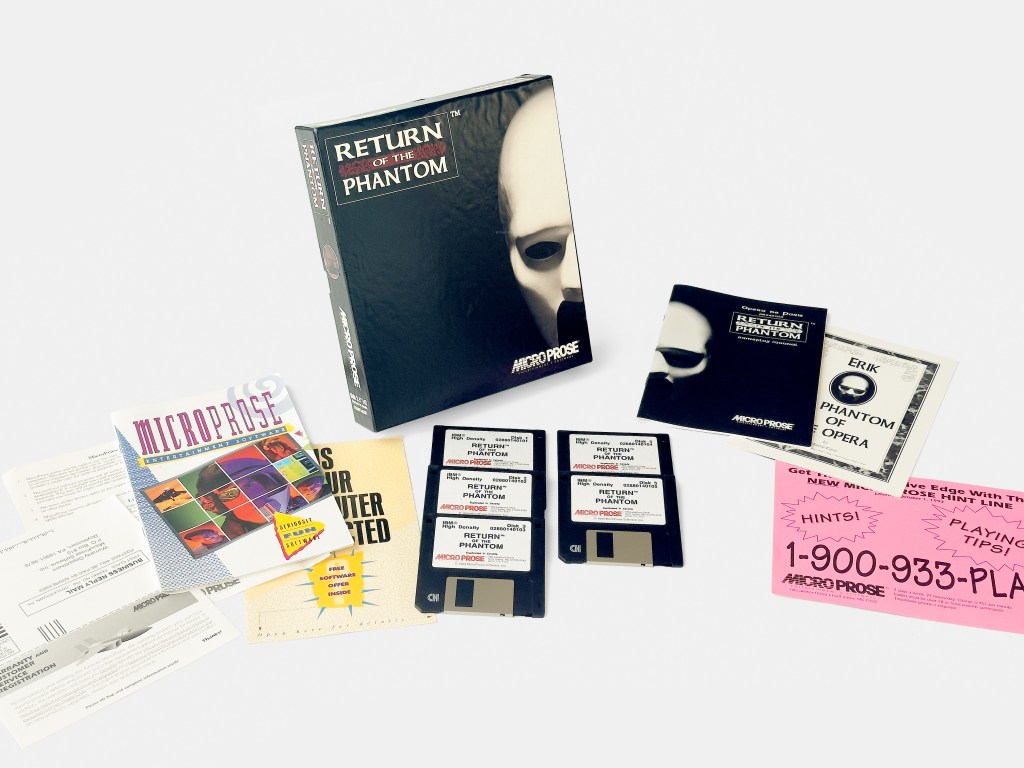

Phantom of the Opera was released in the fall of 1993.

Return of the Phantom was released on floppies and CD-ROM, the latter adding full voiceover for the characters.

Clever packaging design, when placed next to each other the boxes create the full mask

Playing as French inspector Raoul Montand you’re trying to track down the Phantom of the Opera as he strikes again a century after he committed his infamous attack on the Paris Opera House. The use of atmospheric graphics and an original Bach-inspired musical score added to the game’s ambiance.

The CD-ROM version was received as a disappointment for its uninspiring vocals and slow CD access.

Reviewers appreciated Return of the Phantom’s faithful adaptation of an iconic story and its efforts to recreate the atmospheric and mysterious world of the Paris Opera House but its clunky interface, sometimes frustrating gameplay mechanics, slow pace, and non-intuitive puzzles faced some criticism and resulted in a mixed reception.

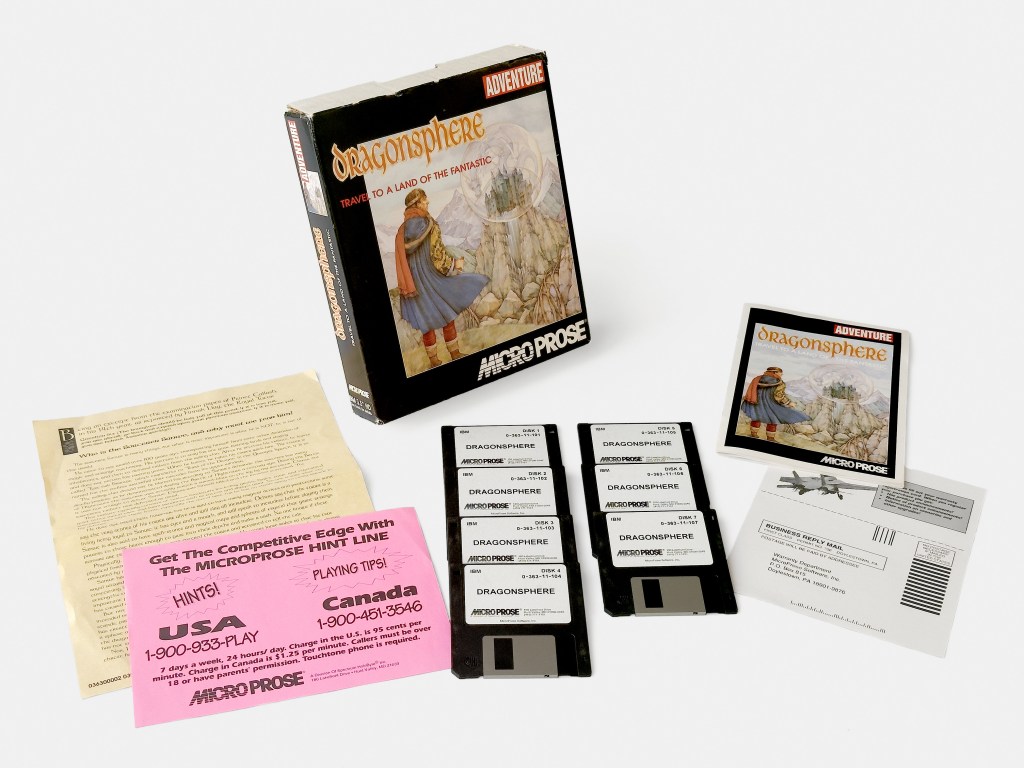

Dragonsphere, the last game to come from the Adventure Group, was similar visually and gameplay-wise to the two earlier games but was set in a fantasy medieval world. It was designed by Douglas Kaufman with Gruson as producer and released in 1994.

Dragonsphere was an ambitious and well-crafted game, boasting a rich and intricately designed world, challenging puzzles, and a somewhat engaging narrative but upon its release in 1994, it lagged behind many of the contemporary games in terms of technology.

The game revolves around the young Callash, recently crowned as the king of Gran Callahach. Two decades prior, the land had faced grave peril at the hands of the evil sorcerer Sanwe, who had sinister plans to conquer and destroy it. The old king’s court wizard, Ner-Tom, had managed to imprison Sanwe using the Dragonsphere spell’s mystical powers. Sanwe, in his defeat, vowed to exact vengeance once the spell’s energy waned. Now, that time has arrived, and the young hero must confront Sanwe before he regains his freedom. Little does he know that his encounter with the sorcerer will lead to profound revelations about his own identity and unravel a sinister new plot.

Dragonsphere was received with positive reviews and praised for its beautiful fantasy setting, intriguing story, and complex dialogue system. Computer Gaming World nominated it as its 1994 Adventure of the Year: Although it lost to Relentless: Twinsen’s Adventure, the nomination served as evidence that the Adventure Group had indeed found its footing. Unfortunately, the acclaim never amassed widespread popularity or significant commercial success.

Despite having sunk considerable sums into the internal Animated Graphic Adventure Group and the Microprose Adventure Development System, none of the three games managed to achieve the hoped-for popularity or commercial success for Microprose. While the titles were released during the heyday of the graphic adventure genre, often referred to as the Golden Age of Adventure Games, a few companies dominated the market, making it challenging for newcomers to secure the attention and investment of consumers. The development of adventure games was becoming increasingly costly, and the pursuit of staying at the forefront of technological advancements required significant success to remain profitable, a feat that none of the three MicroProse titles accomplished.

The Microprose Adventure Development System was sold to Sanctuary Woods, and Gruson, along with Paul Lahaise and Mike Gibson, who had collaborated with Gruson on all three titles, were hired by Sanctuary Woods to contribute to its games.

In 1993, MicroProse, despite having its own internal adventure game development team, sought assistance from struggling British software developer Magnetic Scrolls, which had previously been a prominent figure in the text adventure genre. Together, they collaborated on the creation of the first-person role-playing adventure game The Legacy: Realm of Terror. Regardless of the game’s noteworthy visual presentation, it received only moderate acclaim upon its release in the summer of 1993, a reception consistent with the company’s three traditional third-person point-and-click adventure titles.

Sources: Wikipedia, The Computer Show, Interview with Matt Grusom…