In late spring of 1982, 17-year-old Jordan Melchner finally received the call he had eagerly been awaiting. Earlier, he had submitted his latest Apple II creation, Deathbounce, an Asteroid variant mixed with other already proven concepts, to Doug Carlston’s Brøderbund Software, in the hope of acquiring a publishing deal.

This wasn’t the first time Mechner had submitted a game. Two years earlier, he had submitted a commendable Asteroid clone dubbed Asteroid Blaster to Hayden Book Company. The game was initially accepted for publishing but at the time Atari, who held the right to many of the popular video arcade games, had started threatening legal action against anybody who infringed on their copyrighted properties. Eventually, Hayden pulled the plug and in a last-ditch effort, Mechner transformed parts of the game in an attempt to hide its origins but the respected east-coast book publisher wasn’t ready to fight any potential legal battles with conglomerate Atari and ultimately rejected it.

Mechner had spent a few months of his spare time while a freshman at Yale University programming Deathbounce, the game he had mailed to Brøderbund and now eagerly awaited a response. When the phone rang on May 6th, 1982 he excitedly answered, on the other end, Carlston explained that the game was a bit last year, lacked originality, and rejected it but he did see potential in the young programmer and encouraged him to continue to develop games and promised to ship him a free copy of Dan Gorlin‘s Choplifter, the latest hit title from Brøderbund along with a joystick for him to be able to add joystick support for any upcoming games.

Choplifter showcased a mix of arcade gaming, smooth animation, and cinematic visual aesthetics and resonated extremely well with Mechner who as a kid dreamt of becoming an animator, or even a filmmaker. Inspired by the creative trades Choplifter brought with it, Mechner, between his classes at Yale, started working on his next project, Karateka, a one-on-one fighting game set in feudal Japan. Inspiration came from his fascination with Japanese samurai movies, his recent karate lessons, early Disney cartoons, silent pictures, and Ukiyo-e woodblock print art.

Mechner adapted cartoon and film techniques, like storyboarding, rotoscoping, cross-cutting, wipes, suspense, and storytelling, things he had learned from his ongoing film studies and from participating in film clubs at Yale. Recognizing that the era of rudimentary games was now a thing of the past, the market had moved on and consumers were looking for innovation. Fighting games were nothing new but by incorporating cinematic mechanics and realistic animation previously unseen he could leverage it into a completely new gaming experience.

The following two years were spent developing Karateka, mainly in Mechner’s college dorm room and when home in his parent’s basement. He strived to create the most realistic animation yet seen in a game and since animation typically was the work of programmers it often left much desired. Smooth and realistic animation on the 1 MHz Apple II computer was a tall order, in the best-case scenario the machine could handle eight frames a second but that proved to not be that far from the cartoons Mechner loved.

Using his dad’s Super 8 film camera, Mechner recorded his karate trainer, Dennis performing various moves and attacks, as well as his father engaging in actions like running and climbing on the family car. Every third frame of recorded film was printed out and each individual print traced into the computer. The rotoscoping technique was essential the same Disney animators had used back in 1937 in the studio’s first feature film, Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs.

Pulling from his cinematic and storytelling knowledge, Mechner added an intro to set the stage for a classic tale of good versus evil with short animated cutscenes to help the narrative flow. Each victorious fight would progress the story delivering a more immersive experience than the ordinary run-of-the-mill beat’em up. Carefully designed locations were created combining colors and skillful use of negative space with shadows beneath the characters as an integrated part. Friends Gene Portwood and Lauren Elliot helped with additional graphics and animation.

By the summer of 1984, as Karateka neared completion, Brøderbund, who Mechner six months earlier had sent a copy to, flew Mechner out to California to make a few changes and expand the scope of the game with the assistance of the company’s in-house staff. During the Autumn, Mechner completed the remaining tasks and shipped out copies to Brøderbund for them to handle the copy protection, cover artwork, and printed materials.

In December of 1984, Karateka was released for the Apple II, after two years and two thousand hours of work.

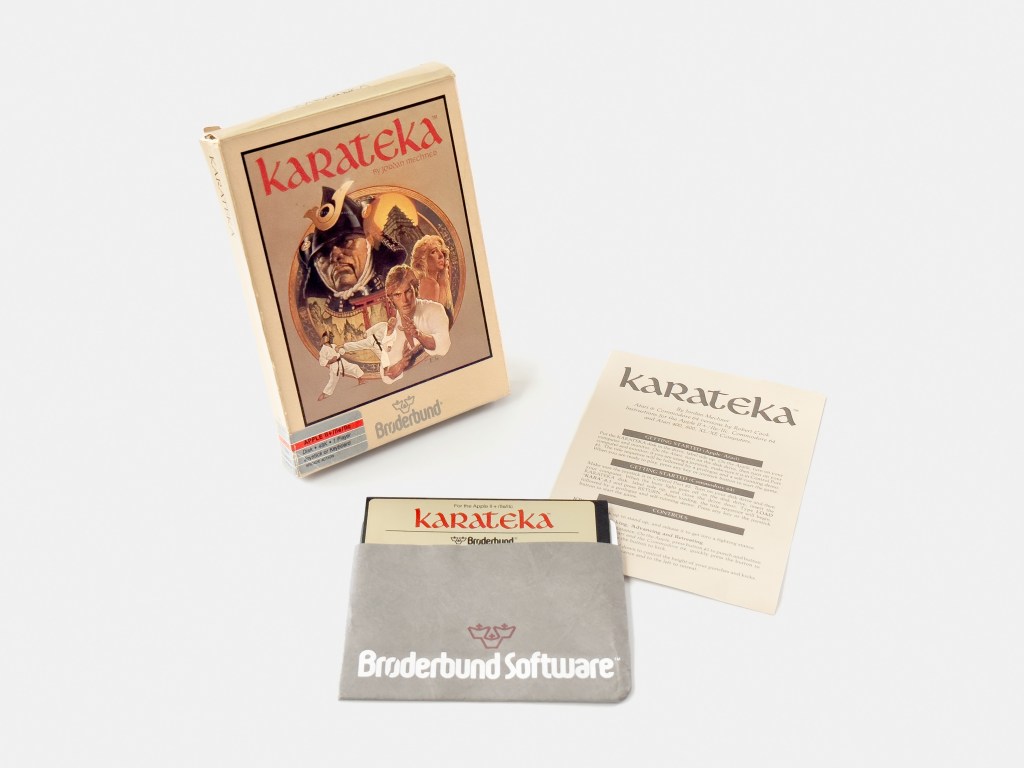

Jordan Mechner’s Karateka was published for the Apple II by Brøderbund in December 1984.

Despite being advertised and sold as a single-sided disk, the reverse side of the disk contained a complete version of the game, turned upside down (like the inserted floppy disk.)

Ascend into Akuma’s mountain fortress and rescue your bride-to-be Princess Mariko. Defeat Akuma’s vicious warriors, his war-trained hawk, and ultimately the evil warlord himself.

Jordan Mechner’s profound understanding of film mechanics is evident throughout Karateka and the rotoscoped animations were unlike anything previously seen. The extremely well-done and coherent artistic style made it one of the best-looking games released for the Apple II.

Mechner’s dad, Francis Mechner, an accomplished classical concert pianist composed the soundtrack.

Sales were off to a slow start as distribution had to be ramped up, yet stores that received copies of Karateka quickly sold out. As the new year took off so did the game, gaining popularity and critical acclaim. The superior animation and movie-like presentation with suspenseful and intense gameplay garnered widespread praise. At the end of January 1985, sales looked to shape up to around 1,000 copies a month. With Mechner’s 15% royalty rate, this amounted to around $30,000 a year, not bad for an 18-year-old college student. When January’s final sales numbers were tallied at the end of February, Brøderbund had moved 1,500 copies.

Mechner now only had a few months left of college and while the Apple II version was on the market and selling moderately, work on the much anticipated Commodore 64 port, done by Robert Cook was starting to lack behind. Intermediate copies were shipped to Mechner to go through and approve but there were still things to attend to, Mechner was determined to ensure that the final version would be nothing short of perfection.

By mid-April, Cook delivered the final Commodore 64 disk of Karateka and the version finally hit the market in the summer of 1985. By now Karateka had climbed to the top of the software charts and with a version ready for the Commodore 64, the best-selling computer at the time, sales were picking up fast.

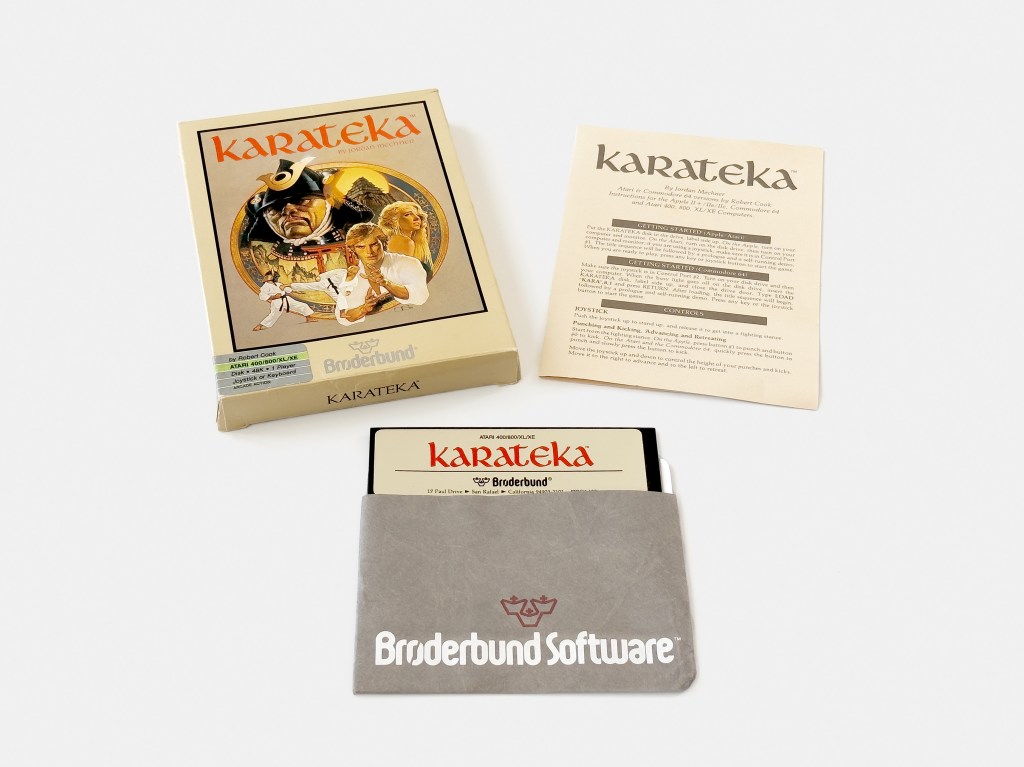

Robert Cook ported Karateka to the Atari 8-bit line of computers and to the newer and more capable Commodore 64.

Mechner considered Cook’s versions to be the best ports, with a few superior features including his dad’s reorchestrated music.

By late 1987 Karateka had become Brøderbund’s best-selling Commodore game.

Versions followed for various systems, including the Nintendo Entertainment Systems. Each version maintained the core gameplay mechanics and storyline but had slight variations to accommodate the specific capabilities of each system. Combined sales eventually passed 500,000 sold copies with 250,000 copies sold within its first month of release in Japan.

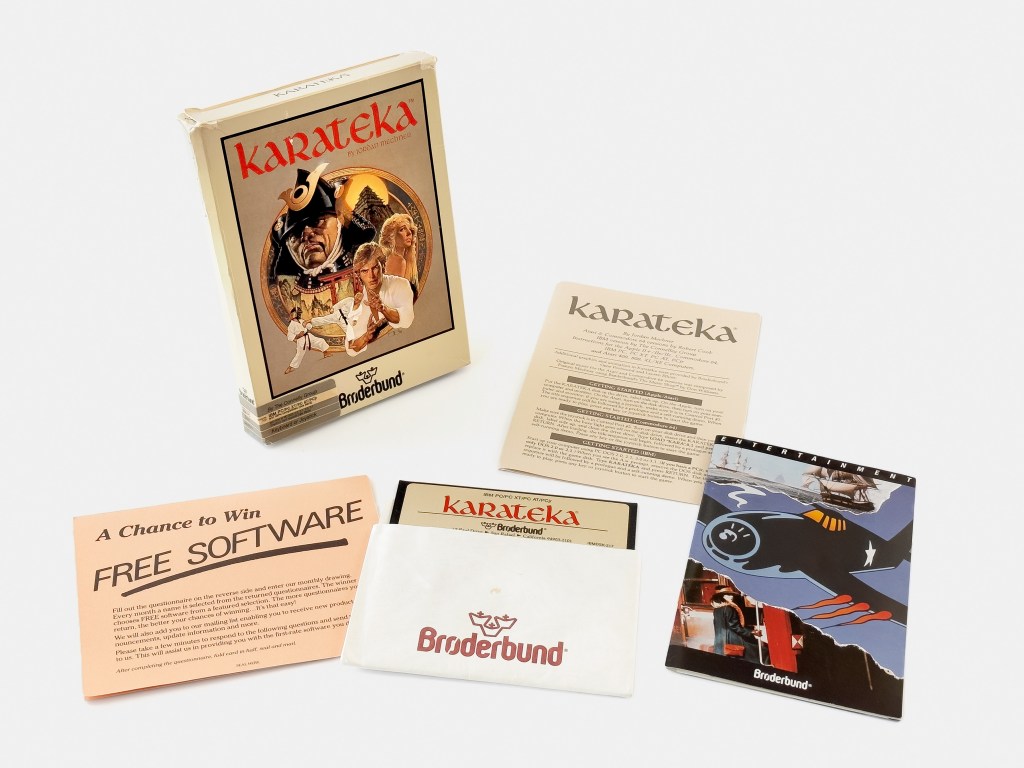

The IBM PC version, done by The Connelley Group was published in 1986

After graduating with a Bachelor of Arts in Psychology from Yale in the summer of 1985, Mechner returned to his hometown of Chappaqua, 30 miles north of New York City. Karateka had gobbled up most of the last two years and he was uncertain if he was ready to do another game and dedicated his time to focus on writing his first screenplay.

As Karateka had made Mechner enough money to pay off his loans from college and a successor, an Arabian Night-inspired story already had been discussed with Brøderbund, it wouldn’t take long before he threw himself into his next and much more ambitious project. It would take another four years before Prince of Persia hit the market in 1989 but that’s all a story for another day.

Nearly 30 years after Karateka’s original release, Mechner was still being interviewed about his pioneering game and started to envision retelling the story without the limitations of the Apple II. Inspiration came from the resurgence of small, independent game studios popping up in 2010 and 2011, and games such as Limbo that created a powerful emotional atmosphere within a limited budget and scope.

In February 2012, Mechner announced that he was leading his own small independent development group to create a remake of Karateka for the Xbox Live Arcade and PlayStation Network. The remake was released in late 2012.

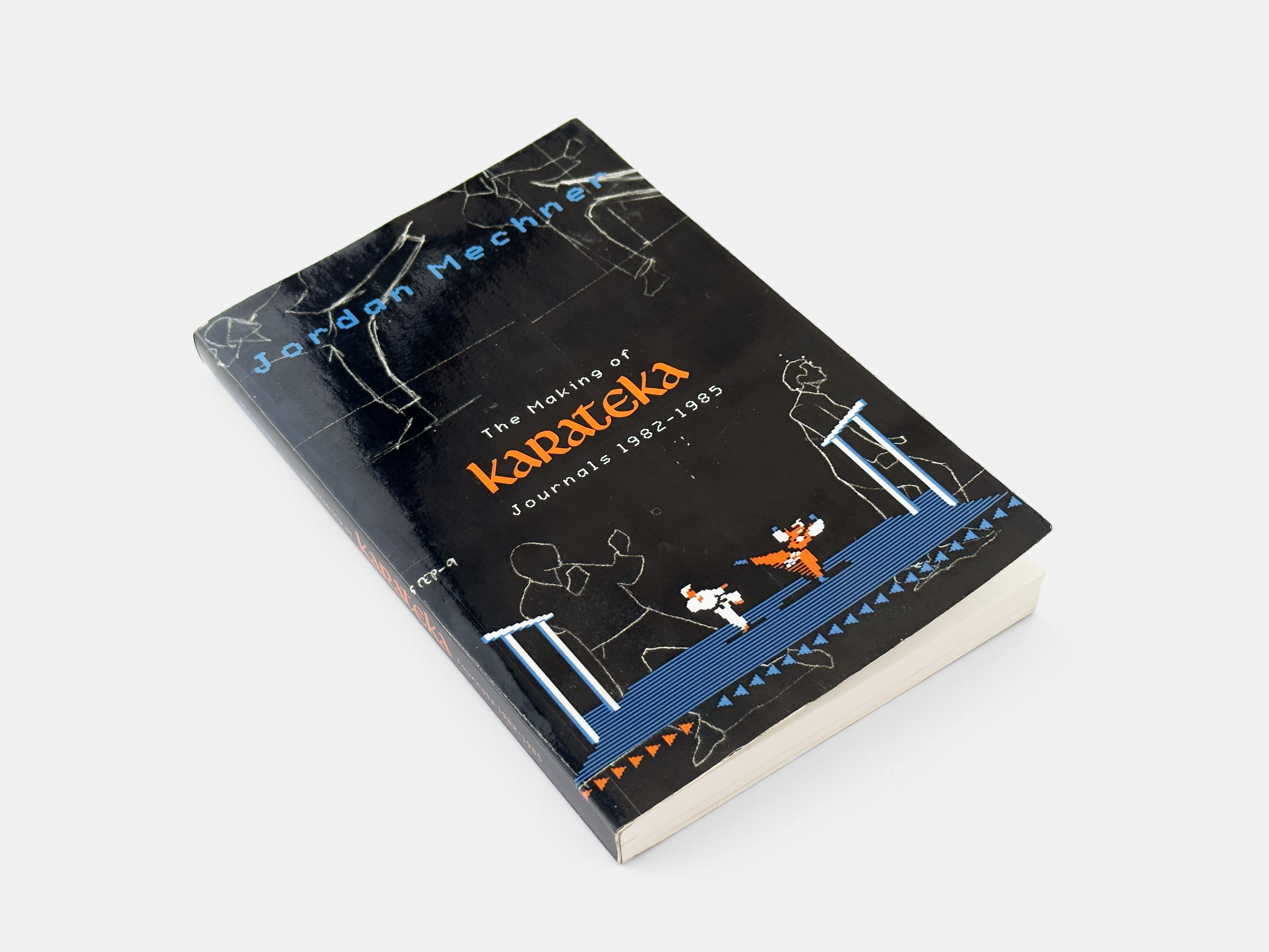

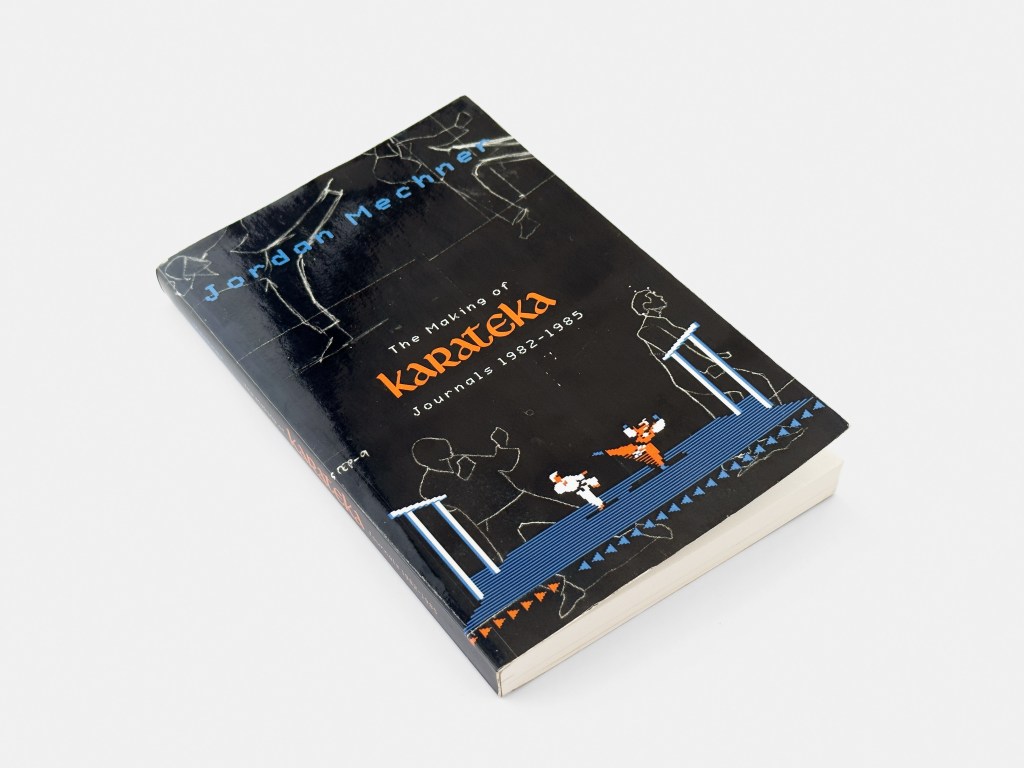

In 1982 Jordan Mechner began keeping a private journal. This first volume is a candid account of the personal, creative, and technical struggles that led to his breakthrough success with Karateka, which topped the bestseller charts in 1985 and planted the seeds of his next game, Prince of Persia.

Sources: Wired, Wikipedia, Game Designers Remembered, jordanmechner.com, Why Now Gaming, The Digital Antiquarian, The Making of Karateka: Journals 1982-1985 by Jordan Mechner, Retro Gamer…

2 thoughts on “Karateka, a stellar debut”