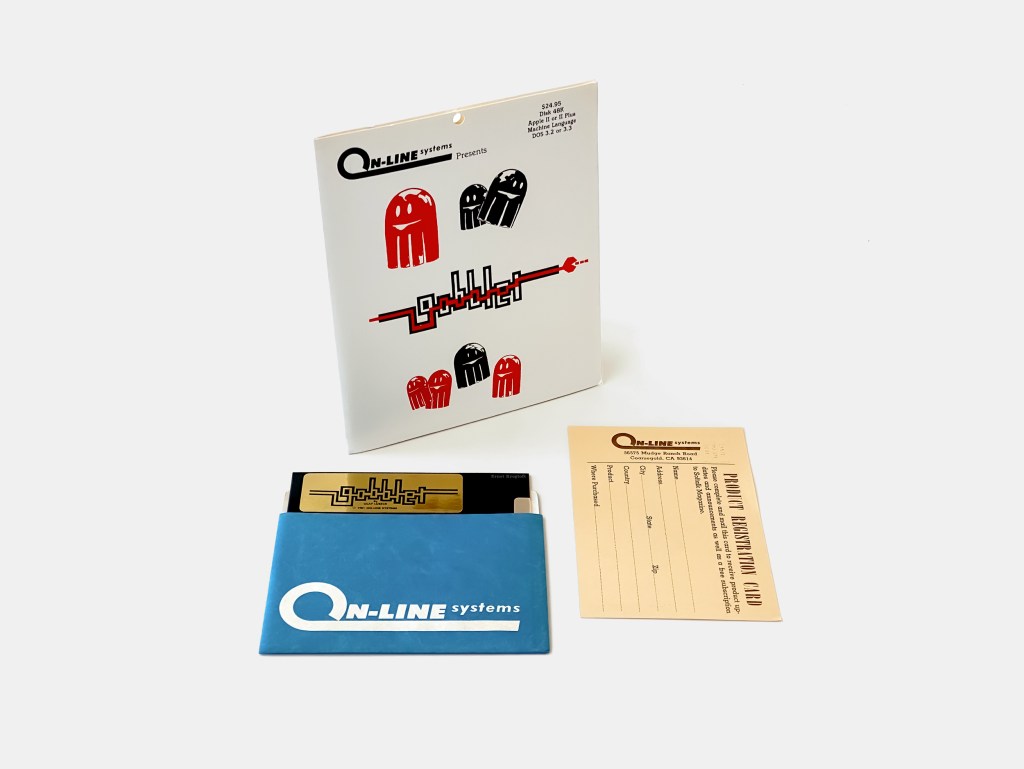

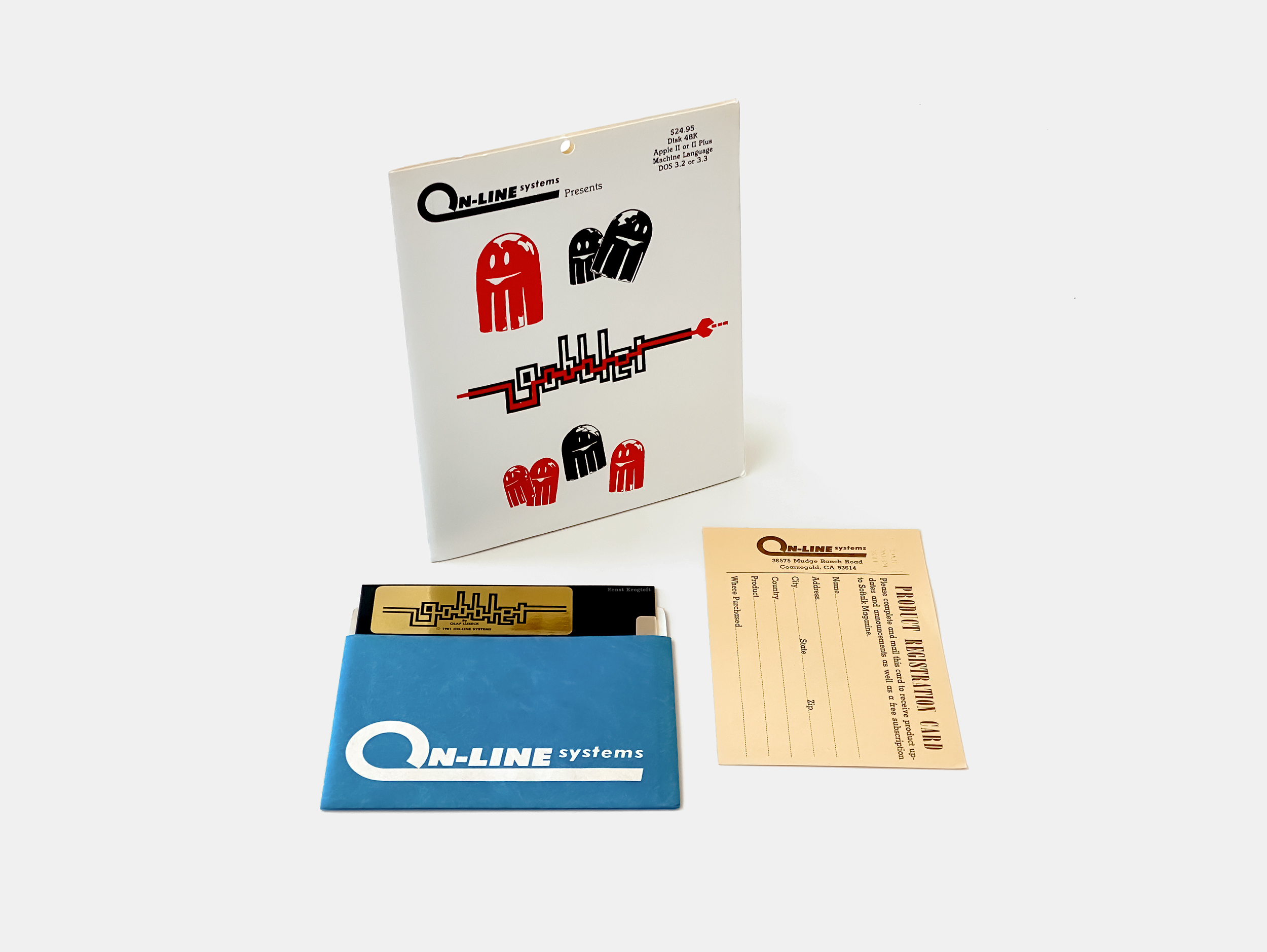

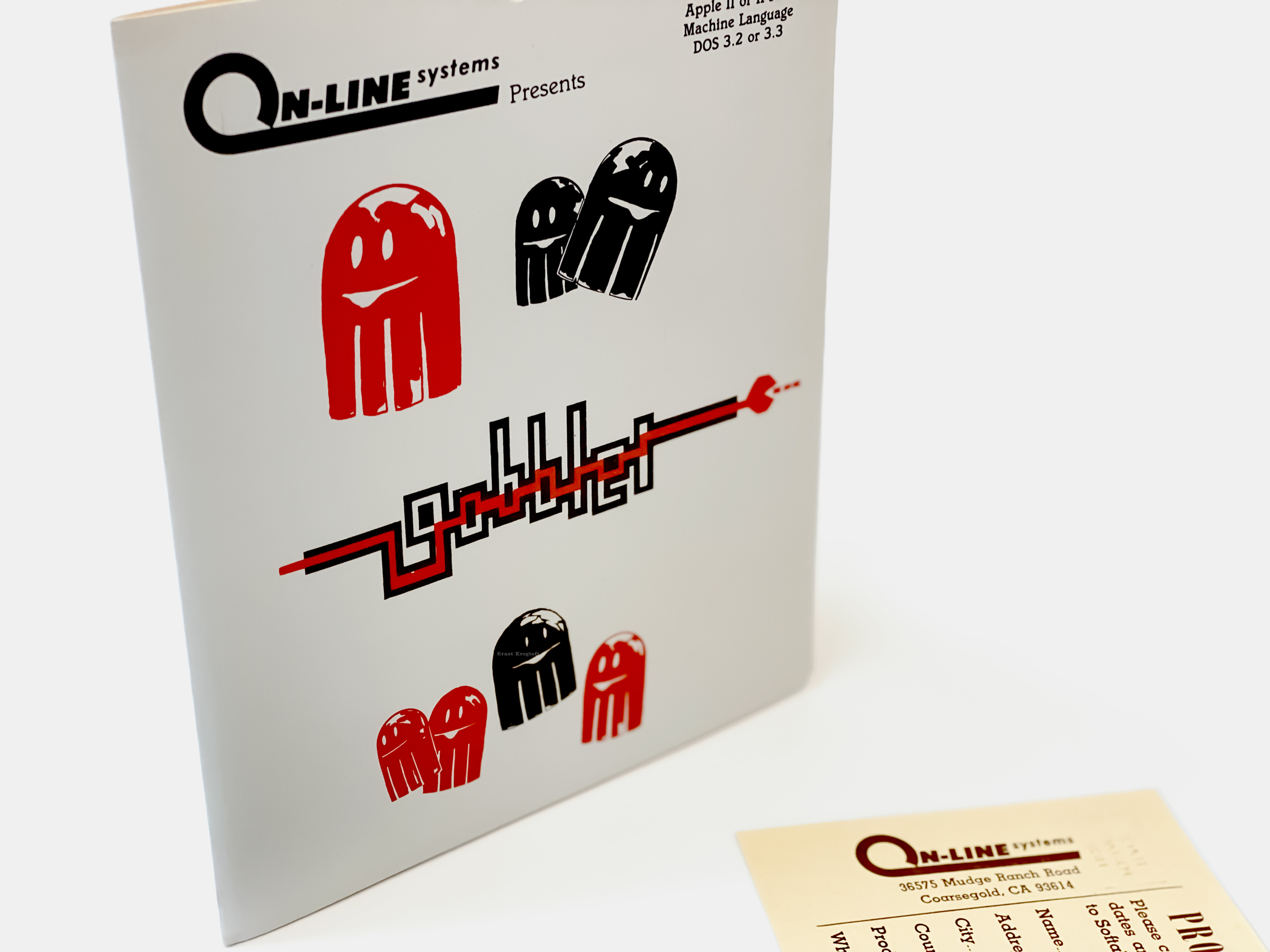

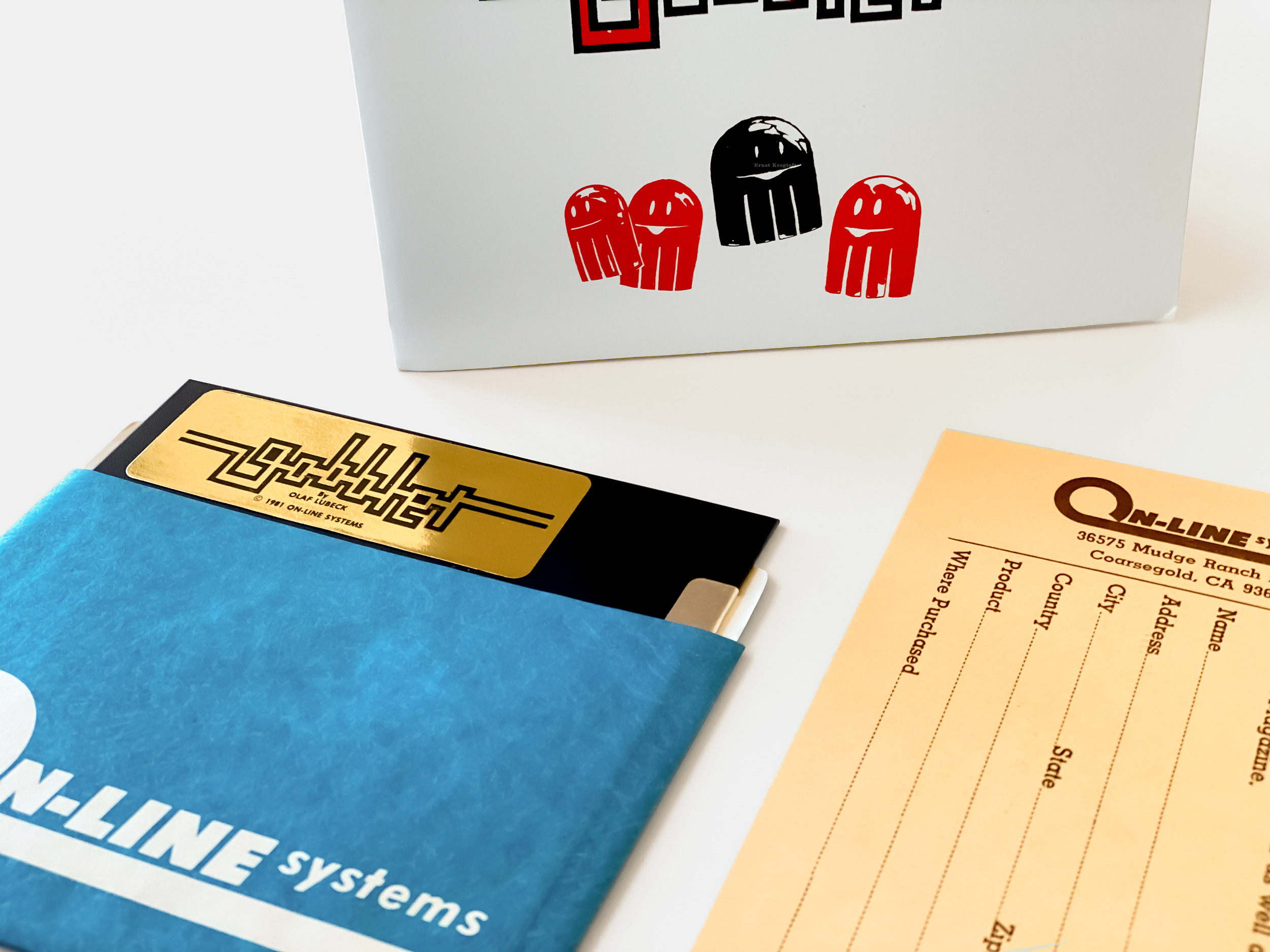

Upon the completion of Ken and Roberta Williams’ first game, Mystery House, in the summer of 1980, Roberta placed a full-page advertisement in Micro 6502 magazine. The ad prominently featured Mystery House, along with two additional and rather subpar titles, Skeetshoot and Trapshoot, both developed by a third party. Despite Skeetshoot and Trapshoot quickly fading into obscurity, the company’s portfolio grew rapidly in the time following with the introduction of numerous new titles in various genres, one being Olaf Lubeck‘s Pac-Man clone, Gobbler.

In 1980 Namco’s easygoing yellow dot-eating Pac-Man arrived from Japan gobbling up video arcade real estate at an unprecedented pace. Unlike many games of that era, Toru Iwatani’s creation was not centered around violence and invading aliens and appealed to a considerably wider audience beyond the usual demographic of young males.

Pac-Man’s cheerful and non-violent nature quickly gained widespread critical and commercial success and became a favorite among video arcade players. By 1981, it emerged as the leading video arcade game, leading to an influx of similar titles from various manufacturers all aiming to capitalize on the already established and proven concept.

The success extended into the home video and computer game market, inspiring countless early game developers, and resulting in a market dominated by rip-offs and clones.

In 1981 Ken Williams put out advertisements in publications like Softtalk and InfoWorld, searching for new developers to further expand the company’s portfolio of games. The ad simply read, with bold letters, “AUTHORS WANTED” and listed below the perks of working with On-Line Systems, including “I (Ken) will personally be available at any time for technical discussions, helping to debug, brainstorming, etc.“.

On-Line Systems “Authors Wanted” ad from InfoWorld in 1981

Among those who came across the advertisement was Pam Lubeck, wife of professional scientific programmer Olaf Lubeck. Lubeck had, while employed as a researcher in the Computer Research and Applications Division of Los Alamos National Laboratory, developed a couple of video arcade clones on his Apple II computer, one of them being a really good Pac-Man called Gobbler. Intrigued by the ad, Lubeck promptly responded by sending in a floppy disk containing his creations. Williams, recognizing the potential of a Pac-Man clone, quickly responded, expressing his interest in marketing and selling the game. The two agreed on a publishing deal and On-Line Systems started selling Lubeck’s Gobbler in 1981.

Olaf Lubeck’s Pac-Man clone, Gobbler was picked up by Ken Williams and published for the Apple II in 1981.

Soon On-Line Systems was on a collision course with conglomerate Atari who held the rights to produce home conversions of Konami’s Pac-Man

There was no doubt, to neither Ken Williams nor anybody else, that Gobbler was a (very well done) copy of Pac-Man. Not only was the visual appearance and gameplay reproduced but the level layout was also nearly identical to Pac-Man.

The Apple II version was the only release of the game.

(The control scheme is a bit weird and takes some time to get used to)

While a focus on copyrights was slowly building at the time, Ken like most didn’t give it too much thought. Replicating and capitalizing on highly popular video arcade games, which already possessed well-established gameplay concepts and proven track records, was tempting and Gobbler proved it.

Gobbler did quite well, selling around 800 copies a month, but by becoming successful and being superior to most other Pac-Man clones at the time, the title soon got the attention of Atari.

Previously, Atari had obtained the rights to produce home versions of Namco’s Pac-Man, a deal that involved significant financial investment. Although Atari had yet to release its official Pac-Man port for the Atari VCS (2600) home video console (the game was under development throughout 1981 and was released in the spring of 1982), they swiftly asserted their copyright ownership and claimed infringement.

Industry-wide cautionary letters sent out by Atari to publications and publishers like On-Line Systems, Brøderbund, and Sirius Software, read:

Atari Software

Piracy

This Game is Over

By 1981 Atari wasn’t the company it had been just years earlier, in the Nolan Bushnell era. Now part of corporate giant, Warner Communications, Atari had achieved massive financial success with sales reaching billions of dollars. However, asserting dominance over smaller companies like On-Line Systems, which had approximately 50 employees at the time, did not sit well with Ken and Roberta.

While it was evident to everyone, including Ken, that Gobbler closely copied Pac-Man, the game proved to be a hit and Ken was reluctant to miss out on potential revenue despite the clear similarities.

When Atari approached Ken, the situation became complex and ambiguous. On one hand, Ken, as a businessman, understood the importance of protecting his own company’s intellectual property, just as Atari did. However, he and Roberta were not about to be bullied by a conglomerate. As the lawsuit took off so did Ken’s nervousness, realizing that Atari was in a position to essentially put him out of business.

Ken hired a lawyer and managed, clearly in his favor, to get the case tried locally. Atari came in at full force trying to intimidate the local judge, implying that the case was beyond his competence. The reality was that few individuals possessed substantial experience in matters of video and computer game copyright infringement.

A court case a year earlier between arcade manufacturer Midway and small hardware manufacturer Dirkschneider, responsible for creating unauthorized clones of popular video arcade games, selling them substantially below the price of genuine machines, had led to what would be known as the ten-foot-rule. If two products from ten feet away didn’t look the same no copyright infringement had taken place. Obviously, the nature of the issue was more complicated than that, nonetheless, the court apparently didn’t find the creative development work behind gameplay and game mechanics as important as visual appearance.

Lubeck was initially to do a conversion of his Gobbler for the Atari 8-bit but a young and determined John Harris (who really didn’t care for the Apple II computer and wasn’t overwhelmed by Gobbler) convinced Ken to let him do a completely new Pac-Man clone for Atari’s home computers. Harris returned to the Hexagon House, one of the properties Ken had acquired to accommodate his young workforce, and within a month, crafted a game that became widely regarded as one of the best-written games for the Atari 8-bit at that time. Unfortunately, it looked remarkably like the game it copied, and with all the ongoing legal stuff involving Atari, Ken needed Harris to make substantial modifications to the game.

In response to the legal concerns, Harris made substantial alterations to where the characters visually would appear unique, added a candy-themed concept, and titled it Jawbreaker. Ken received assurance from his lawyer that Atari’s ownership was limited to the Pac-Man name and characters, rather than the game mechanics themselves. Despite the reassurance, Atari approached On-Line Systems and presented them with the choice of either facing a lawsuit or allowing Atari to assume control of Jawbreaker and market it under the Atari brand.

Initially, Atari managed to obtain a temporary restraining order in the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of California in Fresno prohibiting On-Line Systems from producing or selling Gobbler and Jawbreaker. On-Line Systems filed an antitrust suit, stating that Atari was trying to monopolize any game featuring a maze and dots. Atari countersued and then Midway joined the fight.

As part of the defense, Ken and his lawyer pointed to an earlier Japanese game called Head On, which shared mechanics and to some extent gameplay (a maze with dots) with Pac-Man but was released prior to it, implying that some of the core mechanics of Pac-Man were copied as well.

Also, there was no way for programmers to copy the game code from video arcade games since they were all hard-wired. Every line of code written for Gobbler and Jawbreaker was written from scratch to imitate gameplay and therefore wasn’t a copy of the original code.

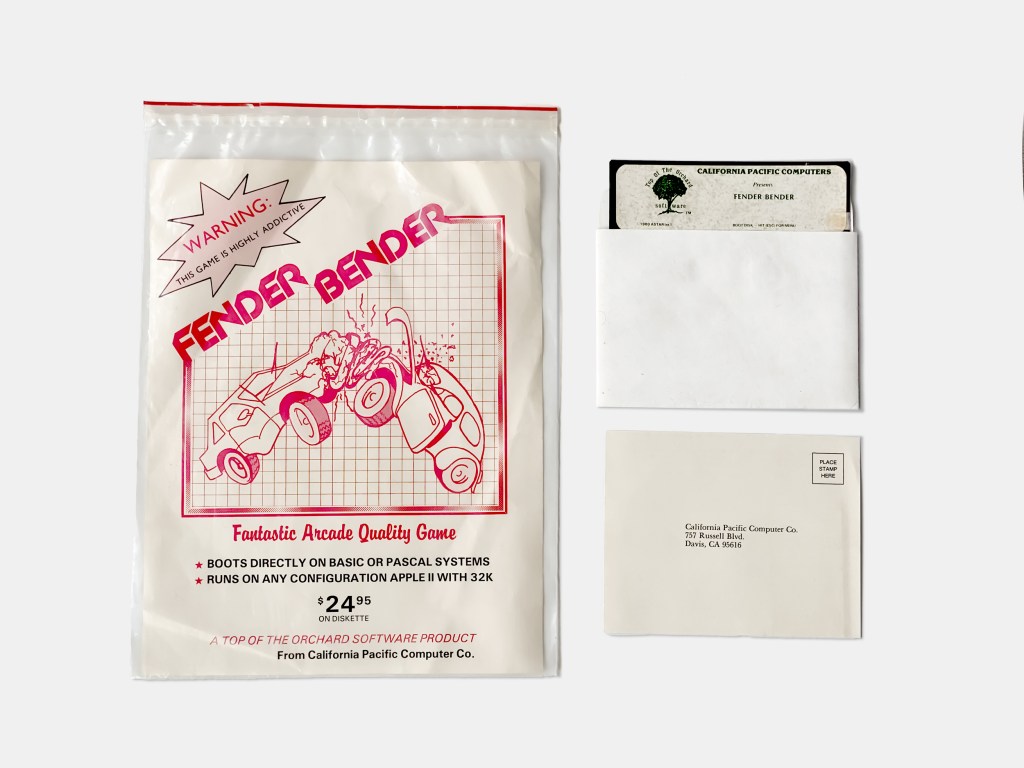

Head On (Fender Bender), developed by Japanese AStar International, was used by Ken and his lawyer as a part of their defense. It shared mechanics such as a maze and dots with Pac-Man but was released prior to it. The game was released in the US in 1980 by California Pacific Computer Company (of Akalabeth and Ultima fame). Initially, as Head On but was retitled to Fender Bender

Eventually, both the Atari and Midway infringement claims were tossed out of court, appealed, and then dismissed again. The parties settled out of court, and copyright law concerning computer games was established as protecting not the mere idea but the specific execution of that idea – in this case protecting the Pac-Man name and its characters but not its gameplay and mechanics.

The lawsuit had a profound impact on Ken, prompting him to remove Gobbler from the market after just five months. In the meantime, Harris had made significant changes to his Jawbreaker to ensure that it sufficiently differed from Pac-Man, giving Ken the confidence to publish it later in 1981. Jawbreaker became a huge success on the Atari 8-bit and was subsequently ported to various other home computers.

Atari’s own, and subpar version (because of technical limitations) of Pac-Man for the Atari VCS (2600) ultimately sold well over seven million copies. A number that utterly dwarfed the number of rip-offs sold, combined across all platforms.

The legal battle between On-Line Systems and Atari was not only a fight of copyrights but also a clash of cultures. The early free-spirited culture that characterized the software and computer industry, exemplified by On-Line Systems, was rapidly fading. Not before long did On-Line Systems transform into Sierra On-Line, a real corporation grown with investment money.

The outcome of the lawsuit would lay precedence, resulting in the home market becoming saturated with countless more or less questionable clones that, in the end, nobody wanted, aiding in the large-scale recession the video game industry went through in 1983-84.

Lubeck would, while continuing his work as a researcher at Los Alamos National Laboratory, continue to partner up with On-Line Systems and in 1982 write Cannonball Blitz…

Sources: Steven Levy: Hackers, Heroes of the Computer Revolution, Wikipedia, InfoWorld, Douglas G. Carlston: Software People, Ken Williams: Not All Fairy Tales Have Happy Endings, Antic Atari 8-bit Podcast…

One thought on “Gobbler, Ken and Roberta Williams take on Atari”